High-Flow Nasal Cannula Outside the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

- Estimate in-hospital (or 28-day) mortality among patients started on HFNC in non-ICU ward settings.

- Determine the proportion of patients requiring ICU transfer after HFNC initiation in internal medicine and respiratory wards.

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria (PICO)

- Population: Adults with acute respiratory failure receiving HFNC outside the ICU.

- Intervention: Ward-initiated HFNC.

- Comparators: COT for DNI comparative data (where available); none for descriptive safety outcomes.

- Outcomes (primary):

- -

- Primary: Mortality and ICU transfer as safety endpoints.

- -

- Secondary: Intubation, LOS, physiologic response, comfort, adverse events.

- Study designs: RCTs and nonrandomized studies (prospective/retrospective cohorts, case series ≥10 patients). Exclusions: We excluded ICU-only or ED-only initiation, peri-operative-only cohorts, pediatrics, and IMCUs/HDUs (including surgical). These were included only in pre-specified sensitivity analyses.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Synthesis Methods and Certainty of Evidence

2.6. Outcomes and Effect Measures

- Single-arm event rates:

- Comparative analyses:

- Heterogeneity assessment:

- Prespecified sensitivity and subgroup analyses:

- Internal medicine/respiratory wards only.

- COVID-19-only cohorts.

- Exclusion of step-up units (IMCU/HDU) and surgical contexts.

- Software:

3. Results

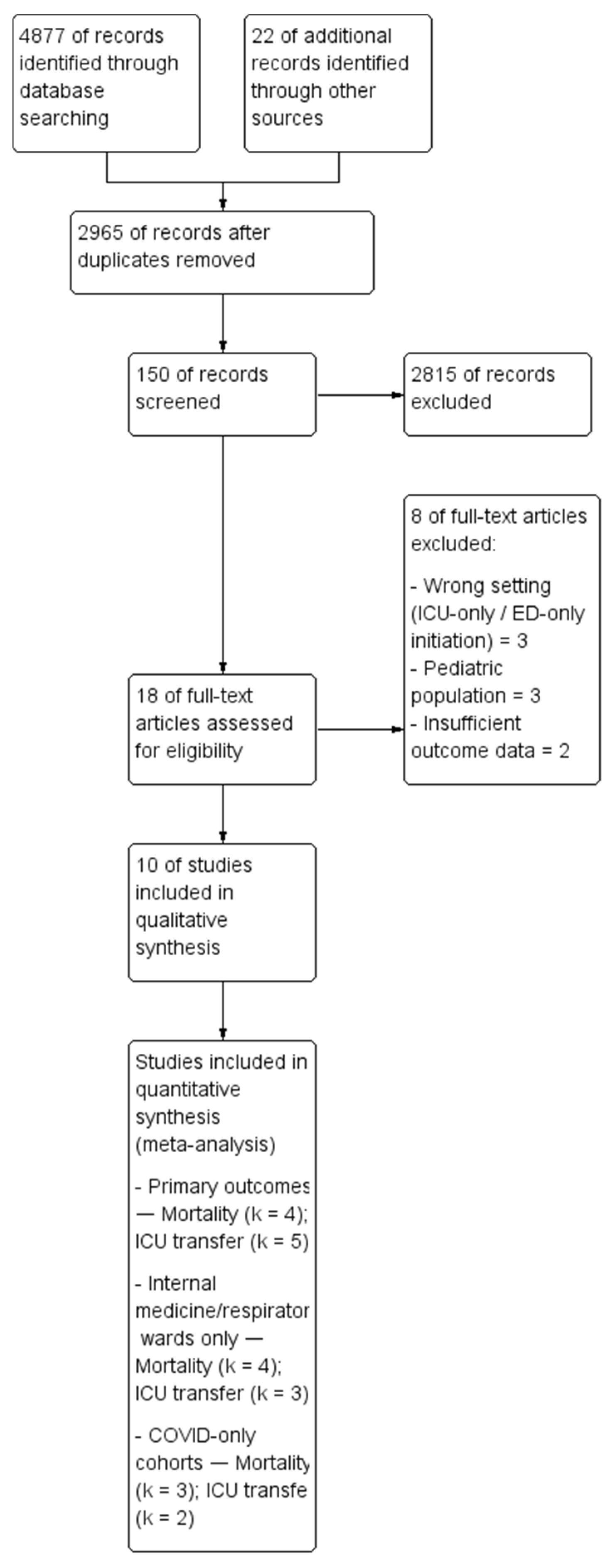

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

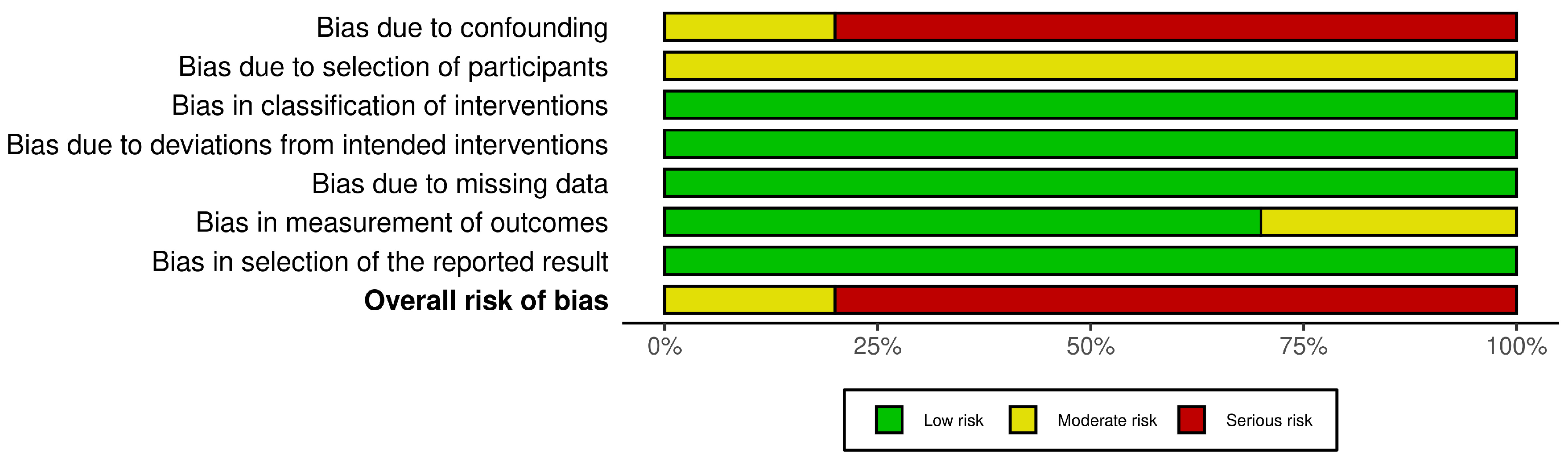

3.3. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

3.4. Results of Syntheses

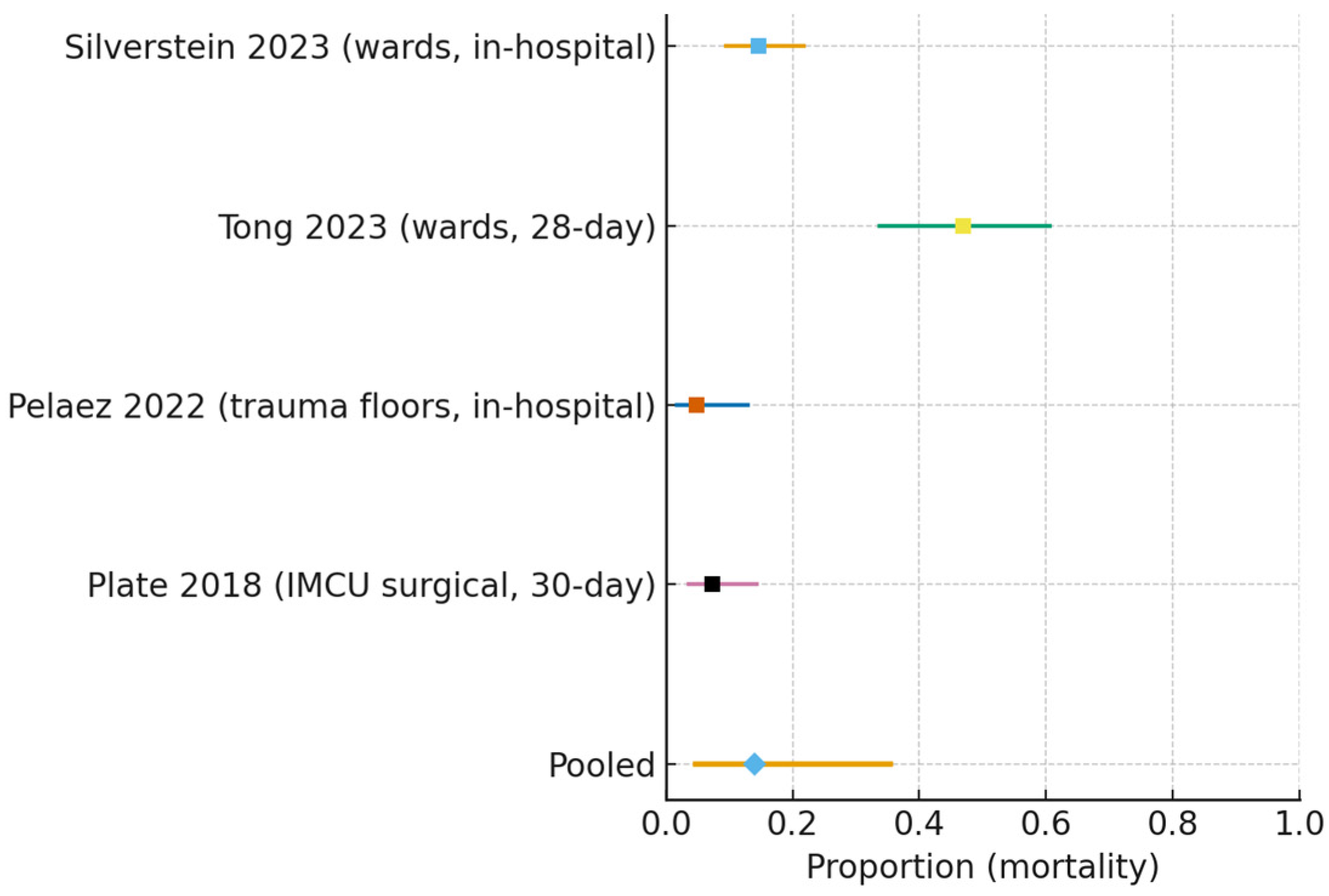

- Mortality (all non-ICU wards):

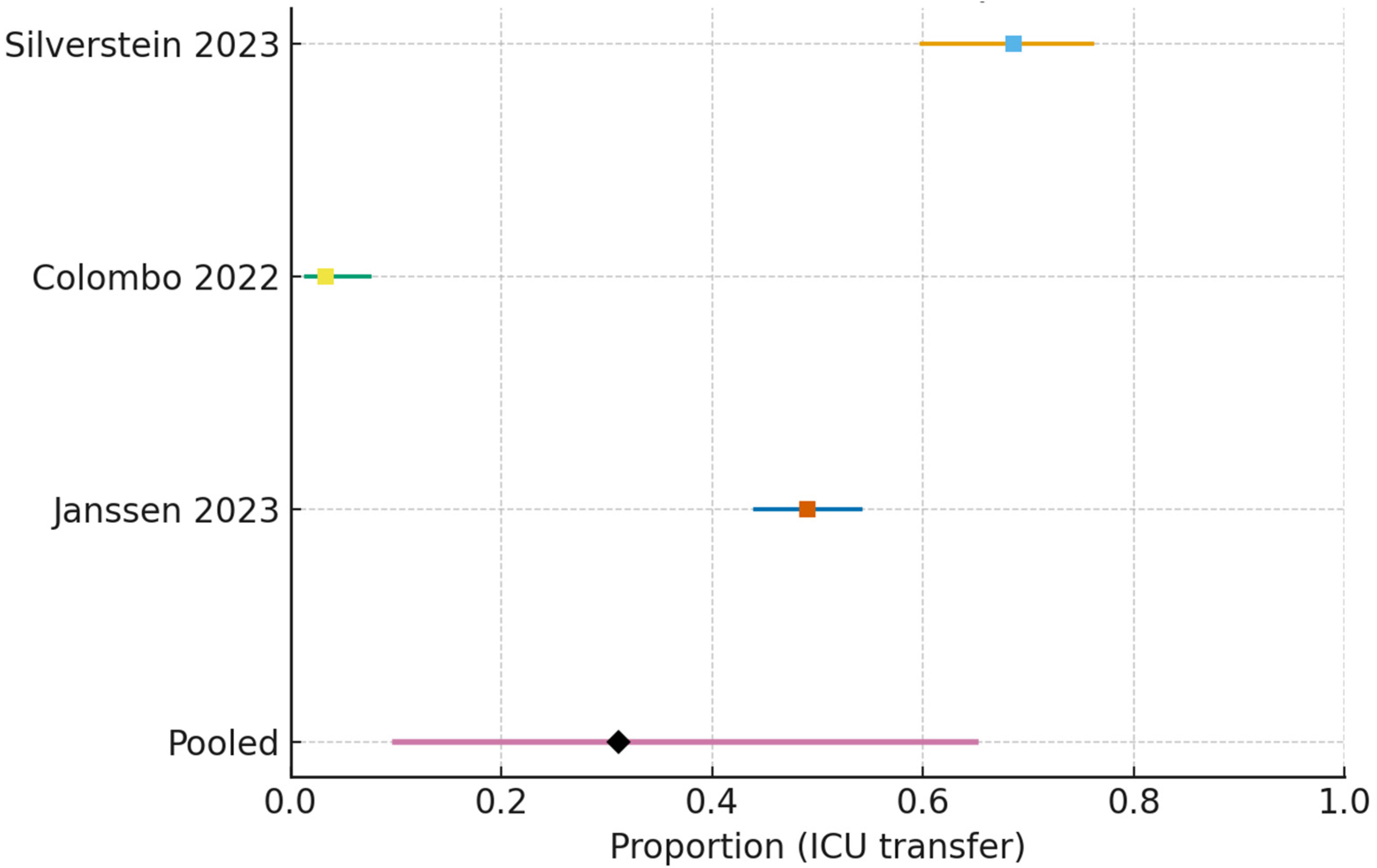

- ICU transfer (all non-ICU wards):

3.5. Subgroup Analyses

3.5.1. Internal Medicine and Respiratory Wards Only

3.5.2. ICU Transfer After Ward-Start HFNC

3.5.3. COVID-19-Only Ward Cohorts

3.6. Subgroup Comparison

Comparison of IM/Resp Wards vs. IMCU/HDU per ICU Transfer

3.7. Certainty of Evidence (GRADE)

3.7.1. Overall Assessment

3.7.2. Mortality (All Non-ICU Wards)

3.7.3. ICU Transfer After Non-ICU Start

3.7.4. DNI COVID-19 (HFNC vs. COT)—Mortality

3.7.5. GRADE—Summary of Findings (IM/Resp Wards)

- In-hospital/28-day mortality (wards):

3.7.6. ICU Transfer After Ward-Start HFNC

3.8. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Clinical Practice and Professional Roles

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Nishimura, M. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy Devices. Respir. Care 2019, 64, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccatonda, A.; Groff, P. High-flow nasal cannula oxygenation utilization in respiratory failure. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 64, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.R.; Baker, P.E.; Parker, R.; Smith, A.F. High-flow nasal cannulae for respiratory support in adult intensive care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD010172. [Google Scholar]

- Grünewaldt, A.; Gaillard, M.; Rohde, G. Predictors of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) failure in severe community-acquired pneumonia or COVID-19. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 20, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, A.; Srour, O.; Malhas, S.E.; Mhanna, M.; Ayesh, H.; Sajdeya, O.; Musallam, R.; Khokher, W.; Kalifa, M.; Srour, K.; et al. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Versus Noninvasive Ventilation in Patients with COVID-19. Respir. Care 2022, 67, 1177–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oczkowski, S.; Ergan, B.; Bos, L.; Chatwin, M.; Ferrer, M.; Gregoretti, C.; Heunks, L.; Frat, J.P.; Longhini, F.; Nava, S.; et al. ERS clinical practice guidelines: High-flow nasal cannula in acute respiratory failure. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Yang, F.; Wang, Q.; Gao, W. Comparison of High Flow Nasal Therapy with Non-Invasive Ventilation and Conventional Oxygen Therapy for Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffet, S.; Boujelben, M.A.; Haudebourg, A.F.; Maraffi, T.; Perier, F.; Labedade, P.; Moncomble, E.; Gendreau, S.; Lacheny, M.; Vivier, E.; et al. High flow nasal cannula and low level continuous positive airway pressure have different physiological effects during de novo acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Ann. Intensive Care 2024, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, L.; Ma, W.; He, H. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: A multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pereña, L.; Ramos Sesma, V.; Tornero Divieso, M.L.; Lluna Carrascosa, A.; Velasco Fuentes, S.; Parra-Ruiz, J. Benefits of early use of high-flow-nasal-cannula (HFNC) in patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia. Med. Clin. 2022, 158, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Arora, U.; Mittal, A.; Aggarwal, A.; Singh, K.; Ray, A.; Jorwal, P.; Soneja, M.; Nischal, N.; Singh, A.K.; et al. Outcomes of HFNC Use in COVID-19 Patients in Non-ICU Settings: A Single-center Experience. Indian. J. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 26, 528–530. [Google Scholar]

- Boccatonda, A.; Cocco, G.; Ianniello, E.; Montanari, M.; D’Ardes, D.; Borghi, C.; Giostra, F.; Copetti, R.; Schiavone, C. One year of SARS-CoV-2 and lung ultrasound: What has been learned and future perspectives. J. Ultrasound 2021, 24, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, C.; Khor, Y.H.; Disler, R.; Naughton, M.T.; Smallwood, N. Ward-delivered nasal high-flow oxygen and non-invasive ventilation are safe for people with acute respiratory failure: A cohort study. Intern. Med. J. 2025, 55, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, J.C.H.; Min, B.N.S.; Tan, S.M.; Teo, W.Q.; Ling, I.T.A.; Wong, J.; Ho, V.K.; Ng, S.Y.; Suhitharan, A.; Thangavelautham, S. Implementation of High-Flow Oxygen Therapy in a Surgical High-Dependency Unit: A Cohort Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e84857. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, S.M.; Scaravilli, V.; Cortegiani, A.; Corcione, N.; Guzzardella, A.; Baldini, L.; Cassinotti, E.; Canetta, C.; Carugo, S.; Hu, C.; et al. Use of high flow nasal cannula in patients with acute respiratory failure in general wards under intensivists supervision: A single center observational study. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plate, J.D.J.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Platenkamp, M.; Meijer, J.; Hietbrink, F. Introducing high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy at the intermediate care unit: Expanding the range of supportive pulmonary care. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2018, 3, e000179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, W.K.; Zipursky, J.S.; Amaral, A.C.; Leis, J.A.; Strong, L.; Nardi, J.; Weinerman, A.S.; Wong, B.M.; Stroud, L. Effect of Ward-Based High-Flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC) Oxygen Therapy on Critical Care Utilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjauw, D.J.T.; Hessels, L.M.; Duiverman, M.L.; Elshof, J.; Janssen, M.L.; Türk, Y.; Heunks, L.; Baart, S.J.; Wils, E.J. High-flow nasal oxygen vs. conventional oxygen therapy in patients with COVID-19 related acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and a do not intubate order: A multicentre cohort study. Respir. Res. 2025, 26, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.K.; Chan, Y.H.; Leung, C.C.D.; Kwok, C.T.; Ng, L.W.; Wong, O.F.; Yeung, Y.C.; Tsang, T.Y.; Chan, N.Y.; Law, C.B. Use of high flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 outside intensive care setting. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 3699–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chang, M.Y.; Zhang, T.; Gow, C.H. Monitoring the Efficacy of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in Patients with Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure in the General Respiratory Ward: A Prospective Observational Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.L.; Türk, Y.; Baart, S.J.; Hanselaar, W.; Aga, Y.; van der Steen-Dieperink, M.; van der Wal, F.J.; Versluijs, V.J.; Hoek, R.A.S.; Endeman, H.; et al. Safety and Outcome of High-Flow Nasal Oxygen Therapy Outside ICU Setting in Hypoxemic Patients With COVID-19. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 52, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaez, C.A.; Jackson, J.A.; Hamilton, M.Y.; Omerza, C.R.; Capella, J.M.; Trump, M.W. High flow nasal cannula outside the ICU provides optimal care and maximizes hospital resources for patients with multiple rib fractures. Injury 2022, 53, 2967–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Year | Nation | Setting | Design | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Key Outcomes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo 2022 [15] | Italy | General wards (nine units, intensivist supervision) | Retrospective observational | 150 adults, mild–moderate AHRF (PaO2/FiO2 150–300) | HFNC up to 60 L/min, ~FiO2 0.5 | None (escalation to NIV/CPAP/ICU if failure) | Failure 19%; ICU transfer 3%; comfort/dyspnea improved; RR decreased | Predictors of failure: higher CCI, higher APACHE II, cardiac failure |

| Zhao 2023 [20] | Taiwan/China | Respiratory ward | Prospective observational | 42 adults with AHRF | HFNC; EIT monitoring | None | Mortality 100% in failures vs. 6% in successes; NLR ≥9 predicts failure; central EIT pattern linked to survival | Small, predictive biomarker focus |

| Silverstein 2023 [17] | Canada | GIM wards (COVID-19) | Retrospective cohort | 124 COVID-19 | HFNC on wards | None (capacity analysis) | Mortality 15%; ICU admission 69%; 47% of ICU-admitted were intubated; +20% critical care capacity | Ward HFNC expanded ICU capacity |

| Janssen 2023 [21] | Netherlands | 10 hospitals; ward vs. ICU starters (COVID-19) | Prospective multicenter observational | 608 COVID-19 (379 ward, 229 ICU) | HFNC (ward) | ICU initiation | Intubation 53% ward vs. 60% ICU (ns); mortality similar; ward starters had more ICU-free days | Ward HFNC safe; no deaths pre-intubation |

| Tong 2023 [19] | Hong Kong | Medical wards (COVID-19 Omicron) | Retrospective observational | 49 COVID-19 | HFNC in ward | None | 28-day survival 53%; SF ratio thresholds at 48–72 h predict mortality | Crisis setting; 28-day used |

| Buchan 2025 [13] | Australia | General wards + RCU (COVID-19) | Cohort study | 668 COVID-19 ARF | NIRS (HFNC 36%, CPAP 20%, NIV 2%) | All received COT | Mortality 7.3%; fewer ICU transfers after RCU implementation | Ward/RCU model feasible |

| Plate 2018 [16] | Netherlands | Standalone surgical IMCU | Case series (retrospective) | 96 admissions (mixed; 70% pulmonary) | HFNC in IMCU | None | ICU transfer 18.8%; 30-day mortality 7%; 162 ICU days avoided | Surgical IMCU context |

| Pelaez 2022 [22] | USA | All hospital floors (trauma) | Comparative vs. historical epoch | 63 ≥ 3 rib fractures (22 managed outside ICU) | HFNC available ward-wide | Historical ICU-only (n = 63) | No differences in mortality/LOS; 27% avoided ICU | Trauma focus |

| Sjauw 2025 [18] | Netherlands | General wards multicenter (DNI COVID) | Multicenter cohort (HFNC vs. COT) | 226 COVID-19 DNI (116 HFNC, 110 COT) | HFNC | COT | Mortality 64% HFNC vs. 71% COT; LOS longer in HFNC; adjusted OR ~0.72 (NS) | DNI-specific comparative |

| Ling 2025 [14] | Singapore | Surgical HDU | Cohort | 89 patients (96 HFOT episodes) | HFOT protocolized with staff training | None | Weaning success 67%; ICU-level support 25% | Implementation study |

| Outcome | Effect (Estimate, 95% CI) | Studies (N)/Design | Certainty of Evidence (GRADE) | Reasons (Downgrading Rationale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MORTALITY (ALL NON-ICU WARDS) | Pooled proportion 0.140 (95% CI 0.046–0.355) | Four studies; observational cohorts | VERY LOW | ↓ Risk of bias (ROBINS-I: serious, nonrandomized); ↓ Inconsistency (I2 ≈ 92%); ↓ Indirectness (mixed in-hospital/30-day; inclusion of IMCU/HDU, some surgical); ↓ Imprecision (wide CI) |

| ICU TRANSFER AFTER NON-ICU START (WARDS/IMCU/HDU) | Pooled proportion 0.200 (95% CI 0.063–0.481) | Five studies; observational cohorts | VERY LOW | ↓ Risk of bias; ↓ Inconsistency (I2 ≈ 97%); ↓ Imprecision (very wide CI); Indirectness not serious for this endpoint |

| MORTALITY (DNI COVID-19)—HFNC VS. COT | RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.75–1.08); adj OR ≈ 0.72 (95% CI 0.34–1.54) | One study; observational comparative | VERY LOW | ↓ Risk of bias; ↓ Indirectness (DNI subgroup, COVID-19-only); ↓ Imprecision (CI includes no effect and harm) |

| Outcome | Effect (Estimate, 95% CI) | Studies (N)/Design | Certainty of Evidence (GRADE) | Reasons (Downgrading Rationale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IN-HOSPITAL/28-DAY MORTALITY | Pooled proportion 0.198 (95% CI 0.071–0.442) | Four studies; observational cohorts | VERY LOW | ↓ Risk of bias (ROBINS-I: serious); ↓ Inconsistency (I2 ≈ 95%); ↓ Indirectness (28-day used when in-hospital unavailable); ↓ Imprecision (wide CI) |

| ICU TRANSFER AFTER WARD-START HFNC | Pooled proportion 0.312 (95% CI 0.099–0.650) | Three studies; observational cohorts | VERY LOW | ↓ Risk of bias (ROBINS-I: serious); ↓ Inconsistency (I2 ≈ 97%); ↓ Imprecision (very wide CI) |

| Outcome | Range or Pooled (If Any) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| INTUBATION | ~53% ward starters vs. ~60% ICU starters (Janssen 2023 [21], ns); ~47% among ICU-transferred (Silverstein 2023 [17], conditional) | Heterogeneous definitions (overall vs. conditional); composite failure endpoints → no pooling |

| HOSPITAL LENGTH OF STAY | Longer LOS in HFNC vs. COT in DNI cohort (Sjauw 2025 [18]); more ICU-free days for ward starters (Janssen 2023 [21]) | Different denominators/time windows; ward vs. hospital LOS inconsistently reported → no pooling |

| PHYSIOLOGIC RESPONSE | SF thresholds at 48–72 h predict mortality (Tong 2023 [19]); RR ↓ and comfort ↑ after HFNC (Colombo 2022 [15]); EIT central pattern and NLR < 9 linked to survival (Zhao 2023 [20]) | ROX/SF/EIT metrics not standardized; timings differ; predictive cutoffs vary |

| PATIENT COMFORT | Improved comfort/dyspnea with HFNC (Colombo 2022 [15]) | Mostly qualitative; lack of validated PROMs; scales differ |

| ADVERSE EVENTS | Rare/minor; no systematic adjudication | Likely under-reporting; definitions absent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boccatonda, A.; Brighenti, A.; D’Ardes, D.; Vetrugno, L. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Outside the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010097

Boccatonda A, Brighenti A, D’Ardes D, Vetrugno L. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Outside the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoccatonda, Andrea, Alice Brighenti, Damiano D’Ardes, and Luigi Vetrugno. 2026. "High-Flow Nasal Cannula Outside the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010097

APA StyleBoccatonda, A., Brighenti, A., D’Ardes, D., & Vetrugno, L. (2026). High-Flow Nasal Cannula Outside the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010097