Factors Affecting Post-EVAR Imaging Surveillance: An Opportunity for Improvement †

Abstract

1. Introduction

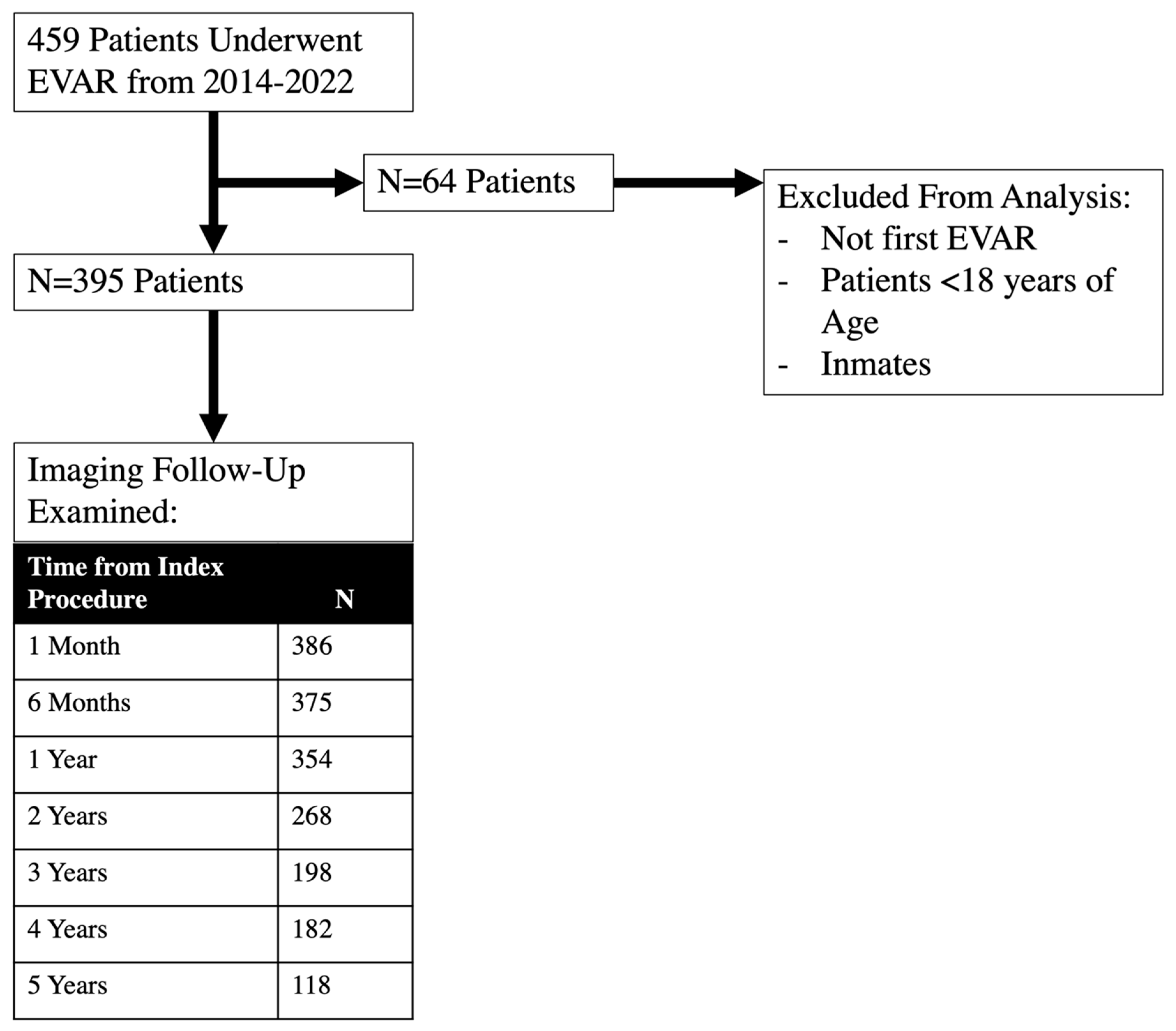

2. Methods

2.1. Institutional Information

2.2. Patient Characteristics

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Analysis

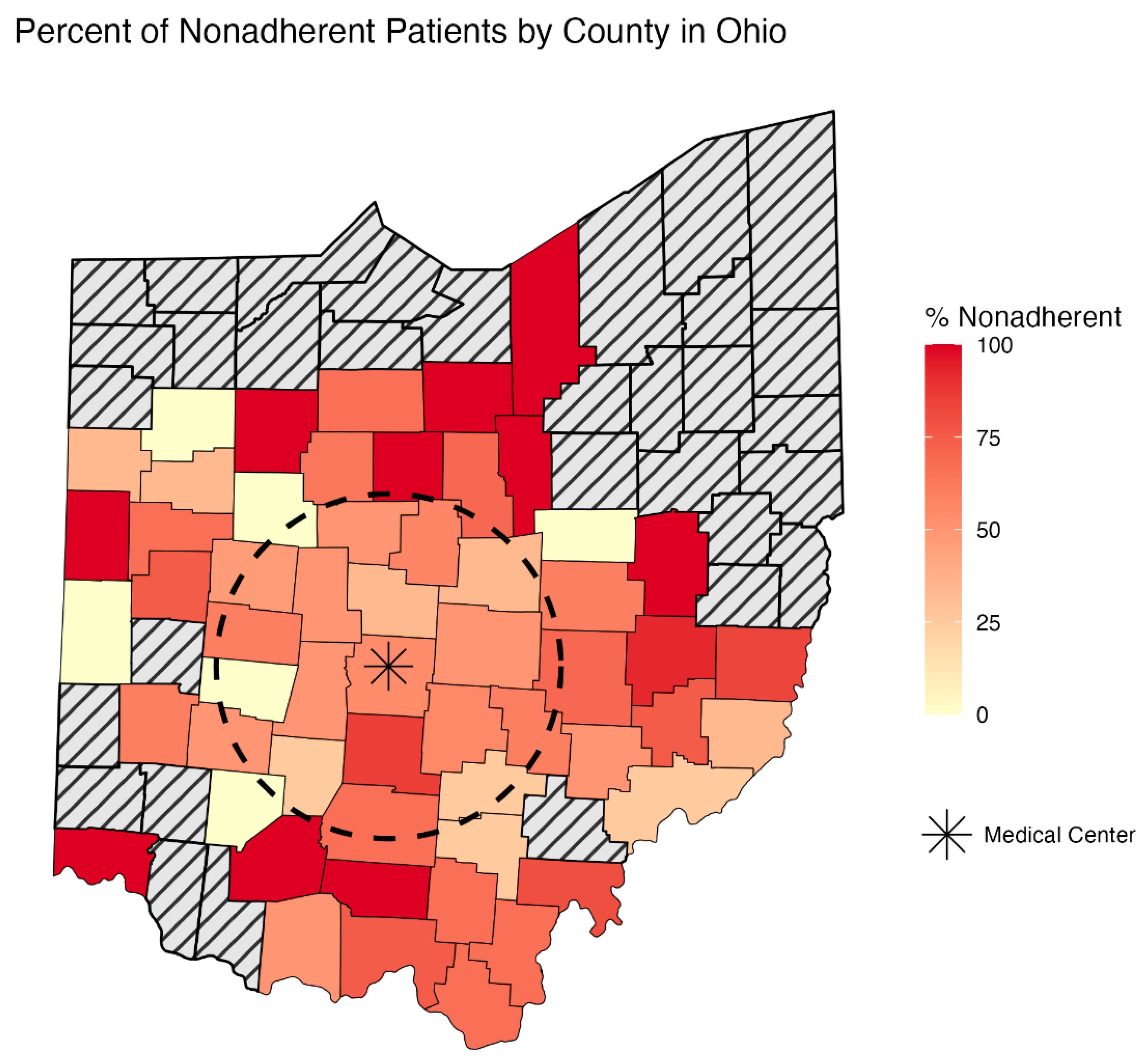

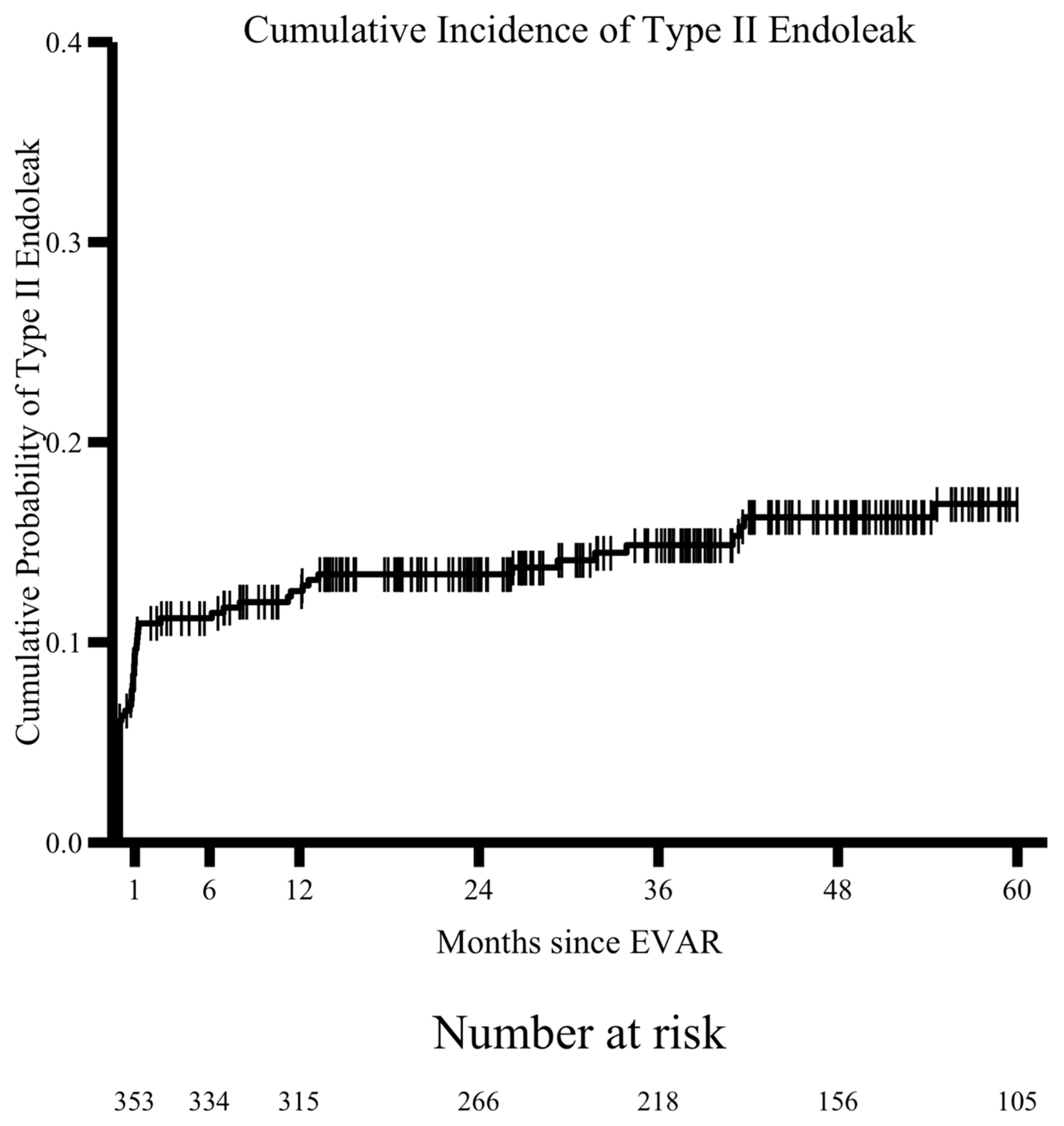

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilmore, B.F.; Scali, S.T.; D′Oria, M.; Neal, D.; Schermerhorn, M.L.; Huber, T.S.; Columbo, J.A.; Stone, D.H. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Care in the United States. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 17, e010374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokosh, R.S.; Wu, W.W.; Schermerhorn, M.; Chaikof, E.L. Society for Vascular Surgery implementation of clinical practice guidelines for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: Postoperative surveillance after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 74, 1438–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes, S.; Mendes, B.C.; Tabiei, A.; Scali, S.T.; Oderich, G.S.; DeMartino, R.R. Management of Endoleaks After Elective Infrarenal Aortic Endovascular Aneurysm Repair: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanh, L.N.; Helenowski, I.; Zamor, K.; Scott, M.; Hoel, A.W.; Ho, K.J. Predictors and Consequences of Loss to Follow-up after Vascular Surgery. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 68, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kind, A.J.H.; Buckingham, W.R. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible—The Neighborhood Atlas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2456–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. 2021 Area Deprivation Index v4. 2024. Available online: https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Chaikof, E.L.; Dalman, R.L.; Eskandari, M.K.; Jackson, B.M.; Lee, W.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Mastracci, T.M.; Mell, M.; Murad, M.H.; Nguyen, L.L.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 2–77.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcaccio, C.L.; O′Donnell, T.F.; Dansey, K.D.; Patel, P.B.; Hughes, K.; Lo, R.C.; Zettervall, S.L.; Schermerhorn, M.L. Disparities in reporting and representation by sex, race, and ethnicity in endovascular aortic device trials. J. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 76, 1244–1252.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanzer, A.; Messina, L.M.; Ghosh, K.; Simons, J.P.; Robinson, W.P., III; Aiello, F.A.; Goldberg, R.J.; Rosen, A.B. Follow-up compliance after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in Medicare beneficiaries. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, C.W.; Zarkowsky, D.S.; Bostock, I.C.; Stone, D.H.; Black, J.H., III; Eldrup-Jorgensen, J.; Goodney, P.P.; Malas, M.B. Endovascular aneurysm repair patients who are lost to follow-up have worse outcomes. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 1625–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraev, T.P.; Durur, E.; Robinson, D.A. Factors Predicting Noncompliance with Follow-up after Endovascular Aneurysm Repair. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 52, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, A.D.; Preiss, J.E.; Ogbuchi, S.; Arya, S.; Duwayri, Y.; Dodson, T.F.; Jordan, W.D.; Brewster, L.P. Longer Patient Travel Times Associated with Decreased Follow-Up after Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair (EVAR). Am. Surg. 2017, 83, e339–e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadis, P.N.; Kyriakidis, K.D.; Paraskevas, K.I. A simple booklet for patient follow-up after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair procedures. Angiology 2012, 63, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.; Ashouri, Y.; Succar, B.; Hsu, C.H.; Abuhakmeh, Y.; Goshima, K.; Devito, P.; Zhou, W. Follow-up compliance in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair at Veterans Affairs hospitals. J. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 80, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Y.; Chen, H.; Gallagher, K.A.; Eliason, J.L.; Rectenwald, J.E.; Coleman, D.M. Predictors of compliance with surveillance after endovascular aneurysm repair and comparative survival outcomes. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 62, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rašiová, M.; Koščo, M.; Pavlíková, V.; Hudák, M.; Moščovič, M.; Kočan, L. Predictors of overall mortality after endovascular abdominal aortic repair—A single centre study. Vascular 2025, 33, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guirguis-Blake, J.M.; Beil, T.L.; Senger, C.A.; Coppola, E.L. Primary Care Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2019, 322, 2219–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Rosenberger, S. Implementing primary care follow-up for high-risk vascular surgery patients. J. Vasc. Nurs. 2024, 42, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooke, B.S.; Stone, D.H.; Cronenwett, J.L.; Nolan, B.; DeMartino, R.R.; MacKenzie, T.A.; Goodman, D.C.; Goodney, P.P. Early primary care provider follow-up and readmission after high-risk surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Percentage of Having a Wellness Visit in Past 12 Months for Adults Aged 18 and Over, United States, 2019–2023. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NHISDataQueryTool/SHS_adult/index.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Mafi, J.N.; Landon, B.E. Proportion of Preventive Primary Care Visits Nearly Doubled, Especially Among Medicare Beneficiaries, 2001–2019. Health Aff. 2023, 42, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.L.; Bitton, A.; Souza, J.; Landon, B.E. Trends in Outpatient Care for Medicare Beneficiaries and Implications for Primary Care, 2000 to 2019. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Adherent N = 174 | Nonadherent N = 221 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.8 ± 8.0 | 70.6 ± 8.3 | 0.157 |

| Male Sex | 144 (82.8%) | 181 (81.9%) | 0.929 |

| Non-white race | 10 (5.8%) | 14 (6.3%) | 0.975 |

| Married | 131 (75.3%) | 160 (72.4%) | 0.595 |

| Distance from medical center (miles) | 39.9 ± 31.5 | 47.2 ± 32.0 | 0.024 * |

| Reside > 50 miles from medical center | 60 (34.7%) | 106 (48.2%) | 0.010 * |

| ADI | 0.053 | ||

| 1st quartile (least deprived) | 20 (12.9%) | 10 (5.2%) | |

| 2nd quartile | 30 (19.4%) | 34 (17.5%) | |

| 3rd quartile | 59 (38.1%) | 78 (40.2%) | |

| 4th quartile (most deprived) | 46 (29.7%) | 72 (37.1%) | |

| Insurance | 0.570 | ||

| Commercial | 49 (28.2%) | 73 (33.0%) | |

| Government-assisted | 122 (70.1%) | 145 (65.6%) | |

| Self-pay | 3 (1.7%) | 3 (1.4%) | |

| CHF | 15 (8.6%) | 23 (10.4%) | 0.670 |

| COPD | 67 (38.5%) | 86 (38.9%) | 1.000 |

| CKD3b+ | 13 (7.5%) | 30 (13.6%) | 0.077 |

| DM | 38 (21.8%) | 47 (21.3%) | 0.989 |

| HTN | 149 (85.6%) | 191 (86.4%) | 0.937 |

| Ever smoker | 158 (90.8%) | 197 (89.1%) | 0.707 |

| Endoleak † | 59 (33.9%) | 68 (30.8%) | 0.579 |

| Type I Endoleak | 4 (2.3%) | 12 (5.4%) | 0.131 |

| Type II Endoleak | 34 (19.5%) | 27 (12.2%) | 0.063 |

| Type III Endoleak | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.4%) | 0.259 |

| Reintervention | 13 (7.5%) | 15 (6.8%) | 0.948 |

| Death | 37 (21.3%) | 54 (24.4%) | 0.534 |

| Characteristic | Univariable OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.159 |

| Female Sex | 1.06 (0.63–1.79) | 0.825 |

| Nonwhite race | 1.11 (0.48–2.56) | 0.808 |

| Married | 0.86 (0.55–1.36) | 0.518 |

| ADI quartiles | 1.33 (1.06–1.68) | 0.014 ß,* |

| Noncommercial insurance | 0.80 (0.53–1.21) | 0.290 |

| CHF | 1.23 (0.62–2.44) | 0.551 |

| COPD | 1.02 (0.68–1.53) | 0.934 |

| CKD 3b+ | 1.04 (0.85–1.27) | 0.701 |

| DM | 0.97 (0.60–1.57) | 0.891 |

| HTN | 1.07 (0.60–1.89) | 0.821 |

| Smoking | 0.83 (0.43–1.62) | 0.587 |

| Reside > 50 miles from medical center | 1.75 (1.16–2.64) | 0.007 ß,* |

| Characteristic | Multivariable OR (95% CI) | p Value | Variance Inflation Factor, VIF (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age † | 0.99 (0.62–1.01) | 0.307 | 1.02 (1.00–3.23) |

| Female Sex † | 1.08 (0.60–1.92) | 0.806 | 1.02 (1.00–5.03) |

| Nonwhite race † | 0.792 (0.210–2.12) | 0.643 | 1.05 (1.00–1.51) |

| ADI quartiles ß | 1.19 (0.92–1.52) | 0.181 | 1.15 (1.06–1.37) |

| Reside > 50 miles from medical center ß | 1.76 (1.10–2.80) | 0.018 * | 1.13 (1.05–1.35) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gage, D.; Campbell, D.B.; Go, M.R.; Teng, X.; Orion, K. Factors Affecting Post-EVAR Imaging Surveillance: An Opportunity for Improvement. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010039

Gage D, Campbell DB, Go MR, Teng X, Orion K. Factors Affecting Post-EVAR Imaging Surveillance: An Opportunity for Improvement. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleGage, Daniel, Drayson B. Campbell, Michael R. Go, Xiaoyi Teng, and Kristine Orion. 2026. "Factors Affecting Post-EVAR Imaging Surveillance: An Opportunity for Improvement" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010039

APA StyleGage, D., Campbell, D. B., Go, M. R., Teng, X., & Orion, K. (2026). Factors Affecting Post-EVAR Imaging Surveillance: An Opportunity for Improvement. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010039