Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Reported Oral Health Status Are Associated with Change in Self-Reported Depression Status: A Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

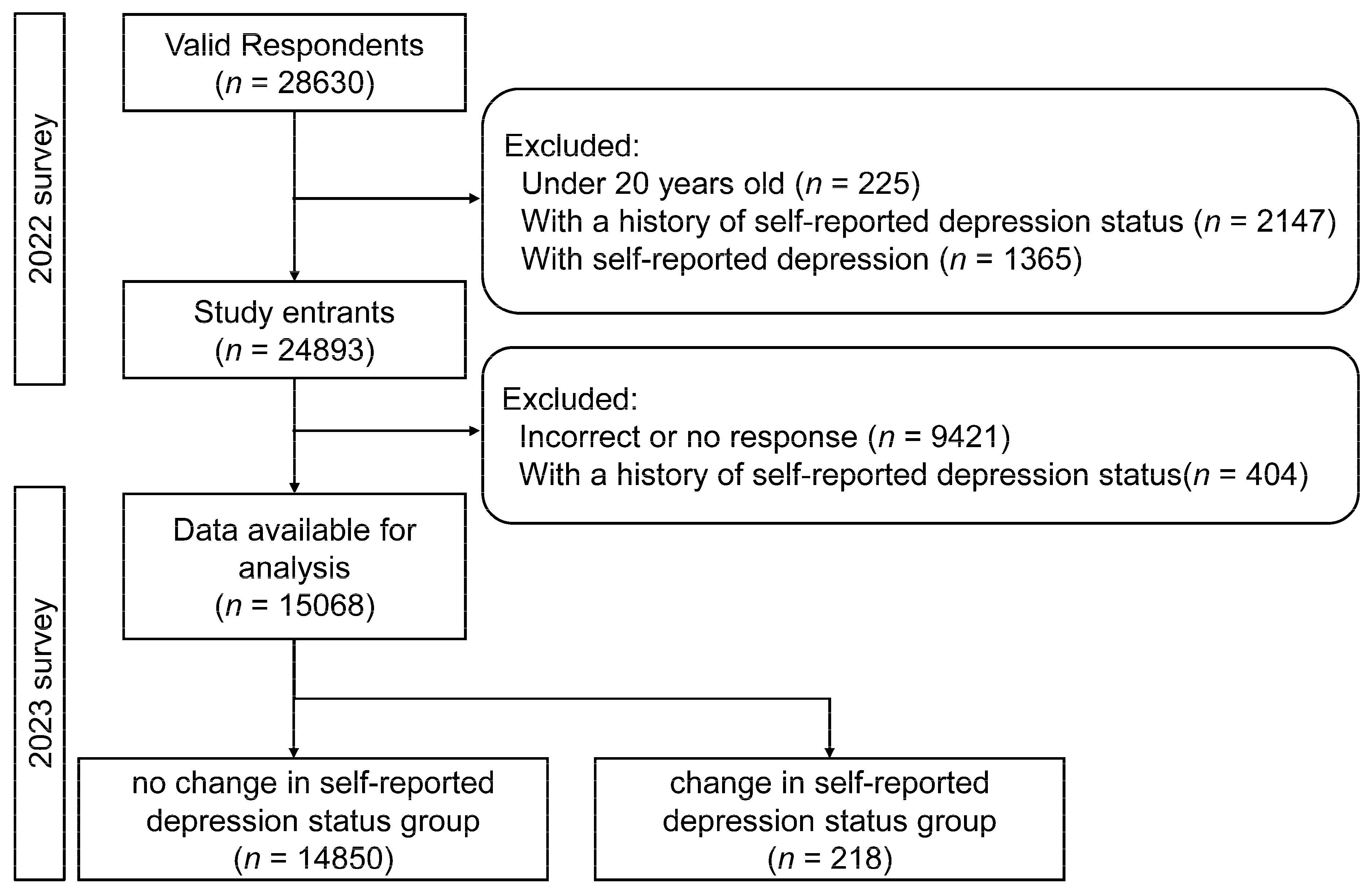

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depression Status

- (1)

- “Never had it”;

- (2)

- “Not currently depressed but have had it in the past”;

- (3)

- “Currently have depression (under treatment with medication)”;

- (4)

- “Currently have depression (under treatment without medication)”;

- (5)

- “Currently have depression (not under treatment)”.

2.2.2. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQOL)

2.2.3. Oral Health Status

Tooth Loss

Periodontal Disease Screening

Oral Pain

Oral Health Behavior

2.2.4. Covariates

Developmental Factors

Sociodemographic and Relationship Characteristics

Lifestyle Factors

Physical Health Status

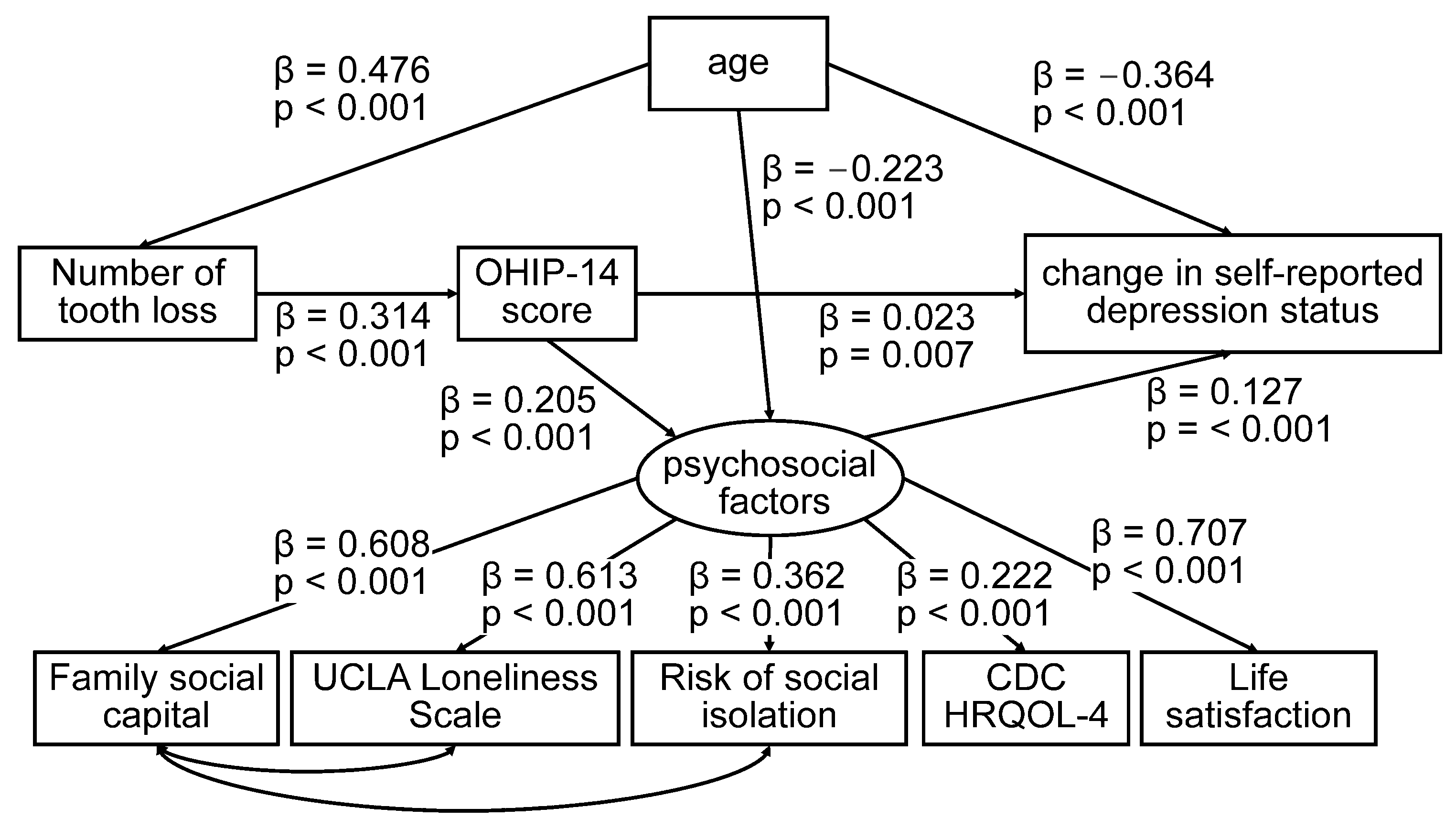

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. AI Software Disclosure

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). 2021. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Older Adults. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- McAllister-Williams, R.H.; Arango, C.; Blier, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Falkai, P.; Gorwood, P.; Hopwood, M.; Javed, A.; Kasper, S.; Malhi, G.; et al. The identification, assessment and management of difficult-to-treat depression: An international consensus statement. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 267, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, R.D.; Zagalo, D.M.; Costa, T.; de Almeida, J.M.C.; Canhão, H.; Rodrigues, A. Exploring depression in adults over a decade: A review of longitudinal studies. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, R.; McDowell, C.P.; De Looze, C.; Kenny, R.A.; Ward, M. Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults Pre– and Post–COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 2251–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondros, P.; Davidson, S.; Wolfe, R.; Gilchrist, G.; Dowrick, C.; Griffiths, F.; Hegarty, K.; Herrman, H.; Gunn, J. Development of a prognostic model for predicting depression severity in adult primary patients with depressive symptoms using the diamond longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Thorpe, L.; Kabir, R.; Lim, H.J. Latent class growth modeling of depression and anxiety in older adults: An 8-year follow-up of a population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Coco, G.; Salerno, L.; Albano, G.; Pazzagli, C.; Lagetto, G.; Mancinelli, E.; Freda, M.F.; Bassi, G.; Giordano, C.; Gullo, S.; et al. Psychosocial predictors of trajectories of mental health distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A four-wave panel study. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 326, 115262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.S.; Li, L.W. Trajectories of social isolation and depressive symptoms in mid- and later life: A parallel process latent growth curve analysis. Aging Ment. Health 2023, 27, 2211–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, T.H.; Ju, Y.J.; Park, E.C. The effect of childhood and current economic status on depressive symptoms in South Korean individuals: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, B.; Maltagliati, S.; Saoudi, I.; Fessler, L.; Farajzadeh, A.; Sieber, S.; Cullati, S.; Boisgontier, M.P. Physical activity mediates the effect of education on mental health trajectories in older age. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 336, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Cho, E. Trajectories of depressive symptoms among community-dwelling Korean older adults: Findings from the Korean longitudinal study of aging (2006–2016). BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Wang, A. Impact of physical activity intensity on longitudinal trajectories of cognitive function and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: Eight-year prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 315, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, T.E.; Rich, J.; Lewin, T.J.; Kelly, B.J. The predictors of depression in a longitudinal cohort of community dwelling rural adults in Australia. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.; Fan, V.S.; Mahadevan, R. How do different chronic condition comorbidities affect changes in depressive symptoms of middle aged and older adults? J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 272, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Lee, I.C.; Su, Y.Y.; Mullan, J.; Chiu, H.C. The longitudinal relationship between mental health disorders and chronic disease for older adults: A population-based study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feter, N.; Rocha, J.Q.S.; Leite, J.S.; Delpino, F.M.; Caputo, E.L.; Cassuriaga, J.; Paz, I.d.A.; da Silva, L.S.; Vieira, Y.P.; Schröeder, N.; et al. Using digital platform for physical activity practice attenuated the trajectory of depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings of the PAMPA cohort. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2023, 25, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; D’Arcy, C. The changing relationship between health risk behaviors and depression among birth cohorts of Canadians 65+, 1994–2014. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1078161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Pei, Y.; Zhong, R. Instrumental support primarily provided by adult children and trajectories of depressive symptoms among older adults with disabilities in rural China. Aging Ment. Health 2023, 27, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemura, K.; Makizako, H.; Lee, S.; Doi, T.; Lee, S.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Shimada, H. Behavioral protective factors of increased depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, e234–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumimoto, K.; Makizako, H.; Doi, T.; Hotta, R.; Nakakubo, S.; Shimada, H.; Suzuki, T. Prospective associations between sedentary behaviour and incident depressive symptoms in older people: A 15-month longitudinal cohort study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iob, E.; Lacey, R.; Giunchiglia, V.; Steptoe, A. Adverse childhood experiences and severity levels of inflammation and depression from childhood to young adulthood: A longitudinal cohort study. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoevers, R.A.; Deeg, D.J.H.; van Tilburg, W.; Beekman, A.T.F. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Co-occurrence and longitudinal patterns in elderly patients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 13, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppa, M.; Luck, T.; König, H.H.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Natural course of depressive symptoms in late life. An 8-year population-based prospective study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lue, B.H.; Chen, L.J.; Wu, S.C. Health, financial stresses, and life satisfaction affecting late-life depression among older adults: A nationwide, longitudinal survey in Taiwan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 50, S34–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohi, T.; Murakami, T.; Komiyama, T.; Miyoshi, Y.; Endo, K.; Hiratsuka, T.; Satoh, M.; Asayama, K.; Inoue, R.; Kikuya, M.; et al. Oral health-related quality of life is associated with the prevalence and development of depressive symptoms in older Japanese individuals: The Ohasama Study. Gerodontology 2022, 39, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, H.; Bjørkløf, G.H.; Engedal, K.; Selbæk, G.; Helvik, A.S. Depression and Quality of Life in Older Persons: A Review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2015, 40, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.M.; Nishita, Y.; Tange, C.; Zhang, S.; Furuya, K.; Shimokata, H.; Otsuka, R.; Lee, M.C.; Arai, H. Association of a lesser number of teeth with more risk of developing depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in Japan: A 20-year population-based cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 174, 111498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenthal, J.C.; Graetz, C.; Plaumann, A.; Dörfer, C.E.; Herzog, W. Number of teeth predict depressive symptoms in a longitudinal study on patients with periodontal disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 89, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, P.; Zojaji, S.; Fard, A.A.; Nateghi, M.N.; Mansouri, Z.; Zojaji, R. The impact of oral health on depression: A systematic review. Spec. Care Dentist. 2025, 45, e13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, S.; Hou, S.; Jiao, X.; Sun, Y. Adverse Impacts of Temporomandibular Disorders Symptoms and Tooth Loss on Psychological States and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life During the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 899582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamat, A.; Smith, J.G.; Melek, L.N.F.; Renton, T. Psychologic Impact of Chronic Orofacial Pain: A Critical Review. J. Oral. Facial Pain. Headache 2022, 36, 103–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anita, H.; Asnely Putri, F.; Maulina, T. The Association Between Orofacial Pain and Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Pain. Res. 2024, 17, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.S.; Ahn, Y.S.; Lim, D.S. Association Between Chewing Difficulty and Symptoms of Depression in Adults: Results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, e270–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dibello, V.; Custodero, C.; Cavalcanti, R.; Lafornara, D.; Dibello, A.; Lozupone, M.; Daniele, A.; Pilotto, A.; Panza, F.; Solfrizzi, V. Impact of periodontal disease on cognitive disorders, dementia, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. GeroScience 2024, 46, 5133–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saletu, A.; Pirker-Frühauf, H.; Saletu, F.; Linzmayer, L.; Anderer, P.; Matejka, M. Controlled clinical and psychometric studies on the relation between periodontitis and depressive mood. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademartori, M.G.; Demarco, F.F.; Freitas da Silveira, M.; Barros, F.C.; Corrêa, M.B. Dental caries and depression in pregnant women: The role of oral health self-perception as mediator. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.J.; Lai, K.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lin, H.Y.; Lin, C.C.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, W.; Chen, W.Y.; Vo, T.T.T.; Lee, I.T. Exploring the Link between Xerostomia and Oral Health in Mental Illness: Insights from Autism Spectrum Disorder, Depression, Bipolar Disorder, and Schizophrenia. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, H.; Nissinen, J.; Lehtiniemi, H.; Salo, T.; Riipinen, P.; Miettunen, J. The Association Between Dental Anxiety And Psychiatric Disorders And Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S. Oral Health Behaviour and Social and Health Factors in University Students from 26 Low, Middle and High Income Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2014, 11, 12247–12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemp, S.; Ziebolz, D.; Haak, R.; Mauche, N.; Prase, M.; Dogan-Sander, E.; Görges, F.; Strauß, M.; Schmalz, G. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Depression or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouxel, P.; Tsakos, G.; Chandola, T.; Watt, R.G. Oral Health-A Neglected Aspect of Subjective Well-Being in Later Life. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouanounou, A. Xerostomia in the Geriatric Patient: Causes, Oral Manifestations, and Treatment. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2016, 37, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, H.; Kelishadi, R.; Heshmat, R.; Motlagh, M.E.; Ranjbar, S.H.; Ardalan, G.; Payab, M.; Chinian, M.; Asayesh, H.; Larijani, B.; et al. Association between junk food consumption and mental health in a national sample of Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Nutrition 2014, 30, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A.; Tachikawa, H.; Midorikawa, H.; Tabuchi, T. Exploring the relationship between personal and cohabiting family members’ COVID-19 infection experiences and fear of COVID-19: A longitudinal study based on the Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey (JACSIS). BMJ Open 2024, 14, e087595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, H.; Suda, T.; Nakamoto, I.; Shinozaki, T.; Tabuchi, T. Changes in social isolation and loneliness prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: The JACSIS 2020–2021 study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1094340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikebe, K.; Watkins, C.A.; Ettinger, R.L.; Sajima, H.; Nokubi, T. Application of short-form oral health impact profile on elderly Japanese. Gerodontology 2004, 21, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Koepsell, T.D.; Hujoel, P.; Miglioretti, D.L.; LeResche, L.; Micheelis, W. Demographic factors, denture status and oral health-related quality of life. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2004, 32, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locker, D.; Matear, D.; Stephens, M.; Lawrence, H.; Payne, B. Comparison of the GOHAI and OHIP-14 as measures of the oral health-related quality of life of the elderly. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2001, 29, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Koyama, R.; Tamaki, N.; Maruyama, T.; Tomofuji, T.; Ekuni, D.; Yamanaka, R.; Azuma, T.; Morita, M. Validity of a Questionnaire for Periodontitis Screening of Japanese Employees. J. Occup. Health 2009, 51, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T. Impact of adverse childhood experience on physical and mental health: A life-course epidemiology perspective. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 76, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.E.; Pollak, S.D. Early life stress and development: Potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2020, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, J. The association between adverse childhood experiences and co-occurrence of health risk behaviors in adolescents: The chained mediating role of self-efficacy and self-control. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, A.; Fu, K.; Jackson, D.B.; Mungia, R.; Oates, T.W.; Nagata, J.M.; Ganson, K.T. Adverse childhood experiences and adult dental care utilization in the United States: Variation by race and ethnicity. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0332880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.; Brocklehurst, P.; Hughes, K.; Sharp, C.A.; Bellis, M.A. Understanding the association between self-reported poor oral health and exposure to adverse childhood experiences: A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usami, K.; Sasahara, S.; Yoshino, S.; Tomotsune, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Matsuzaki, I. Association between perceptions of post-retirement and mental health status of middle-aged workers in Tsukuba Research Park City. J. Phys. Fit. Nutr. Immunol. 2008, 18, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa, S.; Sugisawa, H.; Harada, K.; Sugihara, Y. Psychosocial mediators between socioeconomic status and oral health among urban-dwelling older adults. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2023, 70, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proper, K.I.; Singh, A.S.; van Mechelen, W.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Sedentary behaviors and health outcomes among adults: A systematic review of prospective studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Eguchi, A.; Shigefuku, R.; Nagao, S.; Morikawa, M.; Sugimoto, K.; Iwasa, M.; Takei, Y. Accuracy of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin as a biomarker of chronic alcohol abuse during treatment for alcoholism. Hepatol. Res. 2022, 52, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, T.; Doi, S.; Isumi, A.; Ochi, M. Association of Existence of Third Places and Role Model on Suicide Risk Among Adolescent in Japan: Results From A-CHILD Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 529818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys. Res. Aging. 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 66, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, K.; Kamide, N.; Sakamoto, M.; Sato, H.; Shiba, Y.; Matsunaga, A. Association Between Social Network and Physical Function in Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Japan. Phys. Ther. Res. 2020, 23, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurimoto, A.; Awata, S.; Ohkubo, T.; Tsubota-Utsugi, M.; Asayama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Suenaga, K.; Satoh, H.; Imai, Y. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2011, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubben, J.; Blozik, E.; Gillmann, G.; Iliffe, S.; von Renteln Kruse, W.; Beck, J.C.; Stuck, A.E. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimed-Ochir, O.; Mine, Y.; Okawara, M.; Ibayashi, K.; Miyake, F.; Fujino, Y. Validation of the Japanese version of the CDC HRQOL-4 in workers. J. Occup. Health 2020, 62, e12152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurogi, K.; Ikegami, K.; Eguchi, H.; Tsuji, M.; Tateishi, S.; Nagata, T.; Matsuda, S.; Fujino, Y.; Ogami, A.; CORoNaWork Project. A cross-sectional study on perceived workplace health support and health-related quality of life. J. Occup. Health 2021, 63, e12302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S.; Moriarty, D.G.; Zack, M.M.; Mokdad, A.H.; Chapman, D.P. Self-reported body mass index and health-related quality of life: Findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obes. Res. 2001, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, S.E.; Dongchung, T.Y.; Sanderson, M.L.; Bartley, K.; Levanon Seligson, A. A comparison of the four healthy days measures (HRQOL-4) with a single measure of self-rated general health in a population-based health survey in New York City. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhong, F.; Li, C.-F.; Dong, S.-M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.-E.; Huang, C. Association between oral health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in Chinese college students: Fitness Improvement Tactics in Youths (FITYou) project. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, P.; Zhang, Y.; Choi, J.Y. The Mediating Role of Formal Social Engagement in the Relationship Between Oral Health and Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults in South Korea. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2025, 40, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Shi, L.; He, L. Depression and dental caries in US adults, NHANES 2015–2018. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusama, T.; Kiuchi, S.; Umehara, N.; Kondo, K.; Osaka, K.; Aida, J. The deterioration of oral function and orofacial appearance mediated the relationship between tooth loss and depression among community-dwelling older adults: A JAGES cohort study using causal mediation analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 286, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Hsu, Y.C.; Chen, H.J.; Lin, C.C.; Chang, K.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Chong, L.W.; Kao, C.H. Association of Periodontitis and Subsequent Depression: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Medicine 2015, 94, e2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.; Baelum, V. Factors associated with dental attendance among adolescents in Santiago, Chile. BMC Oral Health 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büchtemann, D.; Luppa, M.; Bramesfeld, A.; Riedel-Heller, S. Incidence of late-life depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. The Limitations of Online Surveys. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questionnaire Items |

|---|

| For the past 7 days, have you… |

| …had trouble pronouncing any words because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …felt that your sense of taste has worsened because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …had painful aching in your mouth? …found it uncomfortable to eat any foods because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …been self-conscious because of your teeth or mouth? …felt tense because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …had to interrupt meals because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …found it difficult to relax because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …been a bit embarrassed because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …been a bit irritable with other people because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …had difficulty doing your usual jobs because of problems with your teeth or mouth? …felt that life in general was less satisfying because of problems with your teeth or mouth …been totally unable to function because of problems with your teeth or mouth? Has been your diet been unsatisfactory because of problems with your teeth of mouth? |

| Variables | Categories | n (%)/Average ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| OHIP-14 score * | 3.8 ± 6.9 | |

| Oral health status | ||

| Number of tooth loss † | None | 7553 (50.1) |

| 1~5 | 6903 (45.8) | |

| 10 or more | 612 (4.1) | |

| Periodontal disease | None | 13,346 (88.6) |

| Yes | 1722 (11.4) | |

| Oral pain | None | 13,379 (88.8) |

| Yes | 1689 (11.2) | |

| Dental visits within 1 year | Yes | 9010 (59.8) |

| None | 6058 (40.2) | |

| Covariates | ||

| Age (years) | 51.9 ± 16.8 | |

| Sex | Male | 7715 (51.2) |

| Female | 7353 (48.8) | |

| Years of Education (years) | 14.4 ± 2.0 | |

| Annual income | <3 million yen | 2560 (21.0) |

| 3–6 million yen | 4819 (39.6) | |

| 6–9 million yen | 2631 (21.6) | |

| >9 million yen | 2155 (17.7) | |

| Smoking history | Never | 9439 (62.6) |

| Past | 3058 (20.3) | |

| Currently | 2571 (17.1) | |

| Excessive alcohol intake | None | 13,795 (91.6) |

| Yes | 1273 (8.4) | |

| Number of diseases | 0.6 ± 1.0 | |

| Participation in hobbies, study, and culture-related activities | Nonparticipation | 13,112 (87.0) |

| Participation | 1956 (13.0) | |

| Walking ≥ 1 h/day or equivalent physical activity | Yes | 6096 (40.5) |

| No | 8972 (59.5) | |

| Relationship with Neighbors | None | 8338 (55.3) |

| Yes | 6730 (44.7) | |

| Chatting/mingling with non-family members | None | 2962 (19.7) |

| Yes | 12,106 (80.3) | |

| Sitting ≥ 240 min/day | Yes | 5639 (38.7) |

| None | 8924 (61.3) | |

| Loss of spouse | None | 13,627 (90.4) |

| Yes | 1441 (9.6) | |

| Financial situation up to age 18 | Not poor | 11,852 (78.7) |

| Poor | 3216 (21.3) | |

| Abuse experience up to age 18 | None | 12,606 (83.7) |

| Yes | 2462 (16.3) | |

| Frequency of eating alone | <1 time/week | 6005 (39.9) |

| 1–5 times/week | 4768 (31.6) | |

| 6–7 times/week | 4295 (28.5) | |

| Habitual use of sleeping pills/anxiolytics | No | 13,911 (92.3) |

| Past use | 354 (2.3) | |

| Current use | 803 (5.3) | |

| Family social capital | 14.6 ± 6.1 | |

| UCLA Loneliness Scale (3-item) | 5.4 ± 2.6 | |

| Risk of social isolation | None | 8686 (57.6) |

| Yes | 6382 (42.4) | |

| CDC HRQOL-4 | Good | 14,650 (97.2) |

| Poor | 418 (2.8) | |

| Life satisfaction | 6.4 ± 2.3 |

| No Change in Self-Reported Depression Status Group (n = 14,850) | Change in Self-Reported Depression Status Group (n = 218) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHIP-14 score * | 3.7 ± 6.9 | 6.0 ± 9.0 | <0.001 ‡ | |

| Oral health status | ||||

| Number of tooth loss † | None | 7437 (50.1) | 116 (53.2) | 0.471 § |

| 1~5 | 6807 (45.8) | 96 (44.0) | ||

| 10 or more | 606 (4.1) | 6 (2.8) | ||

| Periodontal disease | None | 13,157 (88.6) | 189 (86.7) | 0.393 § |

| Yes | 1693 (11.4) | 29 (13.3) | ||

| Oral pain | None | 13,193 (88.8) | 186 (85.3) | 0.101 § |

| Yes | 1657 (11.2) | 32 (14.7) | ||

| Dental visits within 1 year | Yes | 8894 (59.9) | 116 (53.2) | 0.051 § |

| None | 5956 (40.1) | 102 (46.8) | ||

| Covariates | ||||

| Age (years) | 52.0 ± 16.8 | 43.9 ± 15.3 | <0.001 ‡ | |

| Sex | Male | 7590 (51.1) | 125 (57.3) | 0.076 § |

| Female | 7260 (48.9) | 93 (42.7) | ||

| Years of Education (years) | 14.4 ± 2.0 | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 0.262 ‡ | |

| Annual income | <3 million yen | 2513 (21.0) | 47 (26.6) | 0.082 § |

| 3–6 million yen | 4746 (39.6) | 73 (41.2) | ||

| 6–9 million yen | 2605 (21.7) | 26 (14.7) | ||

| >9 million yen | 2124 (17.7) | 31 (17.5) | ||

| Smoking history | Never | 9317 (62.7) | 122 (56.0) | 0.009 § |

| Past | 3016 (20.3) | 42 (19.3) | ||

| Currently | 2517 (16.9) | 54 (24.8) | ||

| Excessive alcohol intake | None | 13,597 (91.6) | 198 (90.8) | 0.724 § |

| Yes | 1253 (8.4) | 20 (9.2) | ||

| Number of diseases | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.8 ± 1.6 | 0.960 ‡ | |

| Participation in hobbies, study, and culture-related activities | Nonparticipation | 12,943 (87.2) | 169 (77.5) | <0.001 § |

| Participation | 1907 (12.8) | 49 (22.5) | ||

| Walking ≥ 1 h/day or equivalent physical activity | Yes | 6025 (40.6) | 71 (32.6) | 0.019 § |

| No | 8825 (59.4) | 147 (67.4) | ||

| Relationship with Neighbors | None | 8205 (55.3) | 133 (61.0) | 0.100 § |

| Yes | 6645 (44.7) | 85 (39.0) | ||

| Chatting/mingling with non-family members | None | 2902 (19.5) | 60 (27.5) | 0.004 § |

| Yes | 11,948 (80.5) | 158 (72.5) | ||

| Sitting ≥ 240 min/day | Yes | 5549 (38.7) | 90 (43.3) | 0.174 § |

| None | 8806 (61.3) | 118 (56.7) | ||

| Loss of spouse | None | 13,428 (90.4) | 199 (91.3) | 0.805 § |

| Yes | 1422 (9.6) | 19 (8.7) | ||

| Financial situation up to age 18 | Not poor | 11,695 (78.8) | 157 (72.0) | 0.018 § |

| Poor | 3155 (21.2) | 61 (28.0) | ||

| Abuse experience up to age 18 | None | 12,456 (83.9) | 150 (68.6) | <0.001 § |

| Yes | 2394 (16.1) | 68 (31.2) | ||

| frequency of eating alone | <1 time/week | 5949 (40.1) | 56 (25.7) | <0.001 § |

| 1–5 times/week | 4683 (31.5) | 85 (39.0) | ||

| 6–7 times/week | 4218 (28.4) | 77 (35.3) | ||

| Habitual use of sleeping pills/anxiolytics | No | 13,749 (92.6) | 162 (74.3) | <0.001 § |

| Past use | 340 (2.3) | 14 (6.4) | ||

| Current use | 761 (5.1) | 42 (19.3) | ||

| Family social capital | 14.6 ± 6.1 | 17.3 ± 6.9 | <0.001 ‡ | |

| UCLA Loneliness Scale (3-item) | 5.4 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | <0.001 ‡ | |

| Risk of social isolation | None | 6322 (42.6) | 60 (27.5) | <0.001 § |

| Yes | 8528 (57.4) | 158 (72.5) | ||

| CDC HRQOL-4 | Good | 14,468 (97.4) | 162 (83.5) | <0.001 § |

| Poor | 382 (2.6) | 36 (16.5) | ||

| Life satisfaction | 6.4 ± 2.3 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | <0.001 ‡ | |

| Independent Variable | Category | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHIP-14 score | — | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | 0.039 | 1.087 |

| Dental visits within 1 year | Yes (Ref) | — | 1.049 | ||

| None | 1.17 | 0.85–1.60 | 0.329 | ||

| Age (years) | — | 0.97 | 0.96–0.99 | <0.001 | 1.246 |

| Sex | Male (Ref) | — | 1.218 | ||

| Female | 1.08 | 0.78–1.52 | 0.637 | ||

| Annual income | >9 million yen (Ref) | — | 1.139 | ||

| 6–9 million yen | 0.64 | 0.38–1.10 | 0.106 | ||

| 3–6 million yen | 0.97 | 0.62–1.51 | 0.883 | ||

| <3 million yen | 1.07 | 0.65–1.77 | 0.787 | ||

| Smoking history | Never (Ref) | — | 1.177 | ||

| Past | 1.28 | 0.83–1.96 | 0.268 | ||

| Current | 1.28 | 0.86–1.92 | 0.221 | ||

| Participation in hobbies, study, and culture-related activities | Nonparticipation (Ref) | — | 1.045 | ||

| Participation | 2.22 | 1.50–3.30 | <0.001 | ||

| Walking ≥ 1 h/day or equivalent physical activity | Yes (Ref) | — | 1.073 | ||

| No | 0.96 | 0.69–1.32 | 0.783 | ||

| Chatting/mingling with non-family members | None (Ref) | — | 1.169 | ||

| Yes | 1.05 | 0.72–1.55 | 0.788 | ||

| Financial situation up to age 18 | Not poor (Ref) | — | 1.122 | ||

| Poor | 0.97 | 0.67–1.41 | 0.864 | ||

| Abuse experience up to age 18 | None (Ref) | — | 1.141 | ||

| Yes | 1.09 | 0.75–1.59 | 0.653 | ||

| Frequency of eating alone | <1 time/week (Ref) | — | 1.177 | ||

| 1–5 times/week | 1.41 | 0.96–2.08 | 0.084 | ||

| 6–7 times/week | 0.87 | 0.56–1.34 | 0.518 | ||

| Habitual use of sleeping pills/anxiolytics | No (Ref) | — | 1.030 | ||

| Past use | 1.97 | 1.06–3.68 | 0.033 | ||

| Current use | 3.51 | 2.27–5.44 | <0.001 | ||

| Family social capital | — | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 | 0.715 | 1.498 |

| UCLA Loneliness Scale (3-item) | — | 1.22 | 1.14–1.30 | <0.001 | 1.342 |

| Risk of social isolation | None (Ref) | — | 1.235 | ||

| Yes | 1.17 | 0.81–1.68 | 0.408 | ||

| CDC HRQOL-4 | Good (Ref) | — | 1.048 | ||

| Poor | 2.92 | 1.81–4.72 | <0.001 | ||

| Life satisfaction | — | 0.90 | 0.84–0.97 | 0.005 | 1.496 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Takeuchi, N.; Maruyama, T.; Toyama, N.; Katsube, Y.; Tabuchi, T.; Ekuni, D. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Reported Oral Health Status Are Associated with Change in Self-Reported Depression Status: A Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010376

Takeuchi N, Maruyama T, Toyama N, Katsube Y, Tabuchi T, Ekuni D. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Reported Oral Health Status Are Associated with Change in Self-Reported Depression Status: A Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010376

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakeuchi, Noriko, Takayuki Maruyama, Naoki Toyama, Yuzuki Katsube, Takahiro Tabuchi, and Daisuke Ekuni. 2026. "Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Reported Oral Health Status Are Associated with Change in Self-Reported Depression Status: A Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010376

APA StyleTakeuchi, N., Maruyama, T., Toyama, N., Katsube, Y., Tabuchi, T., & Ekuni, D. (2026). Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Reported Oral Health Status Are Associated with Change in Self-Reported Depression Status: A Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 376. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010376