Propranolol Reduces Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Large Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

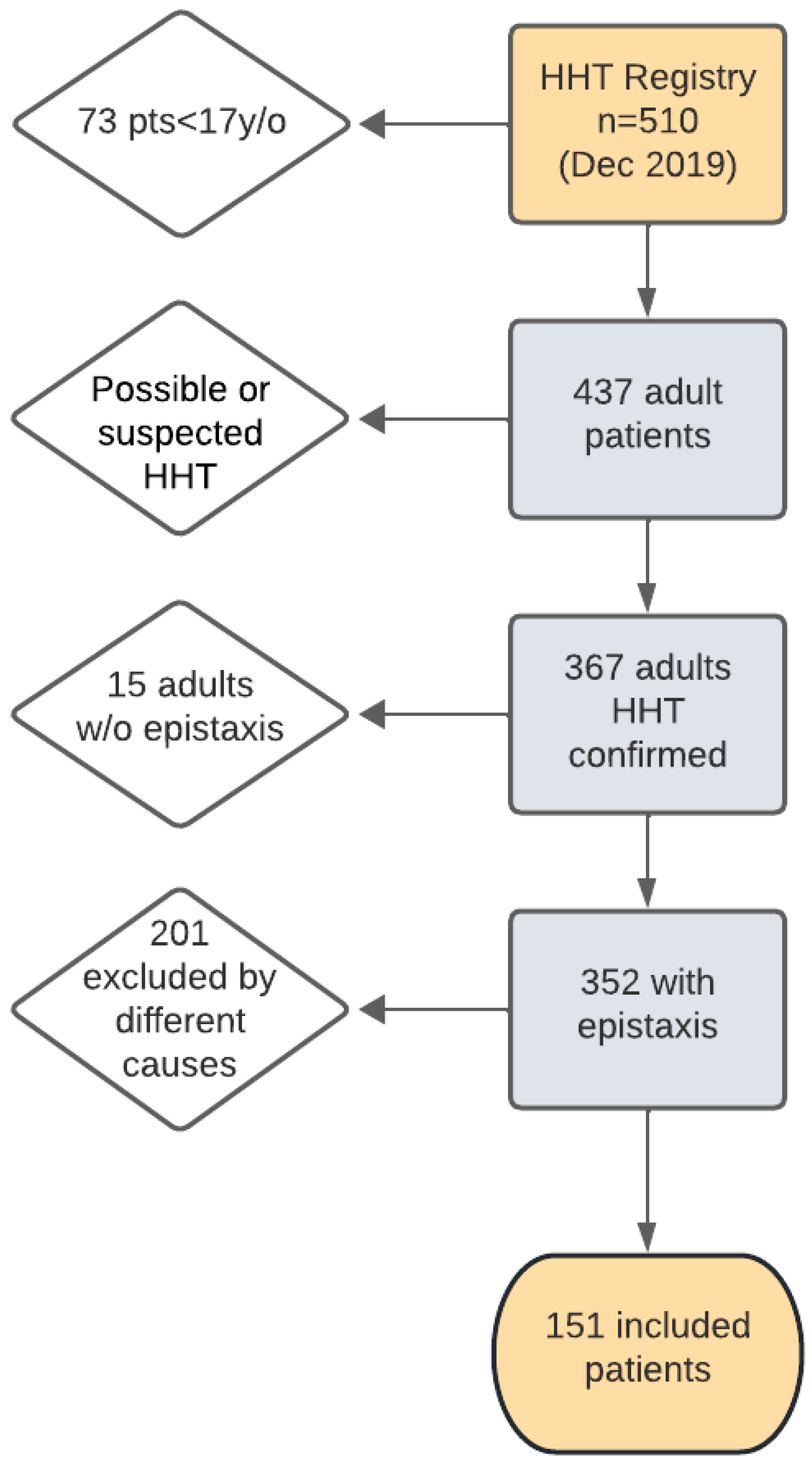

2.1. Patients

2.2. Variables

2.3. Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results for Propranolol Dosage

3.2. Results for Gastrointestinal Bleeding

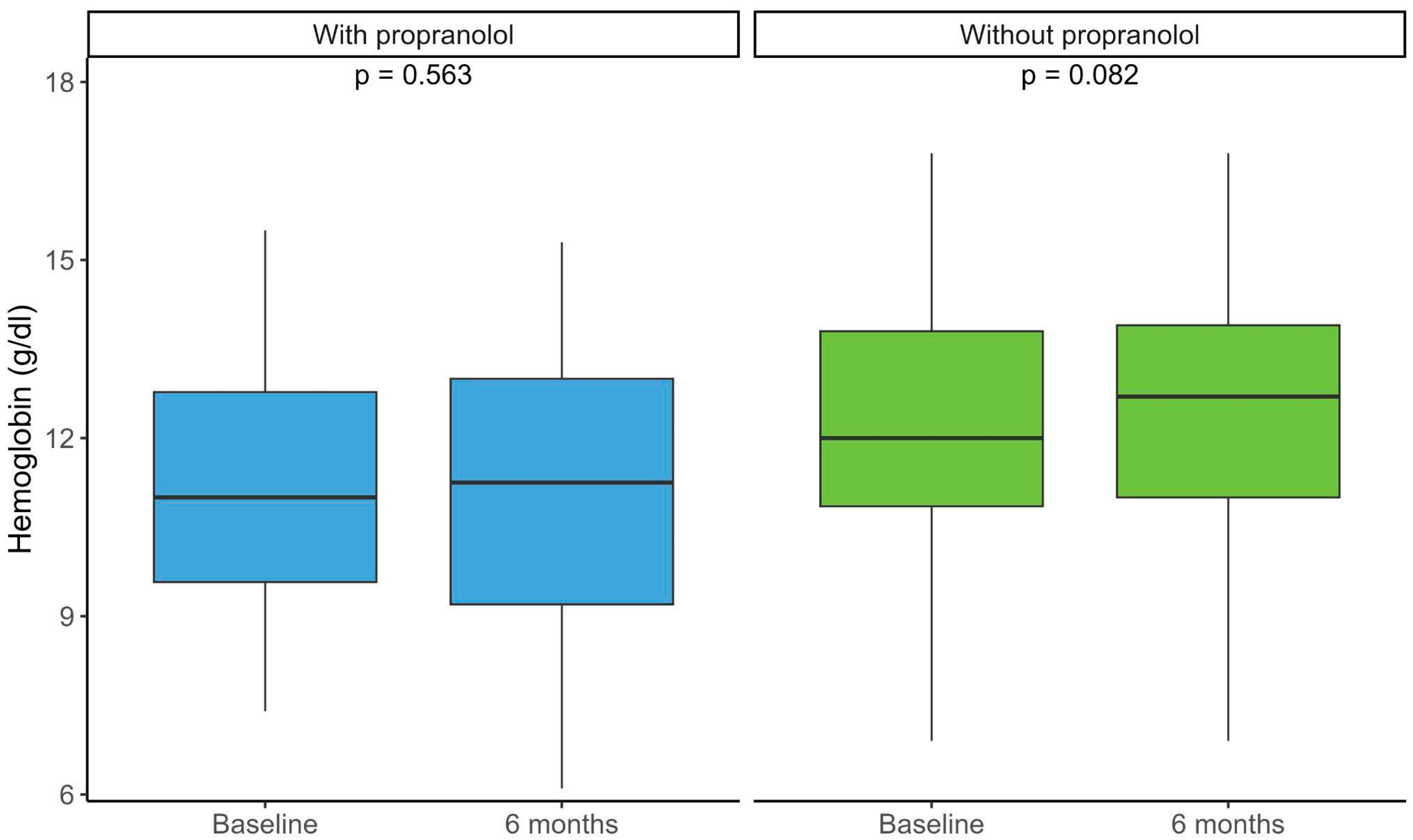

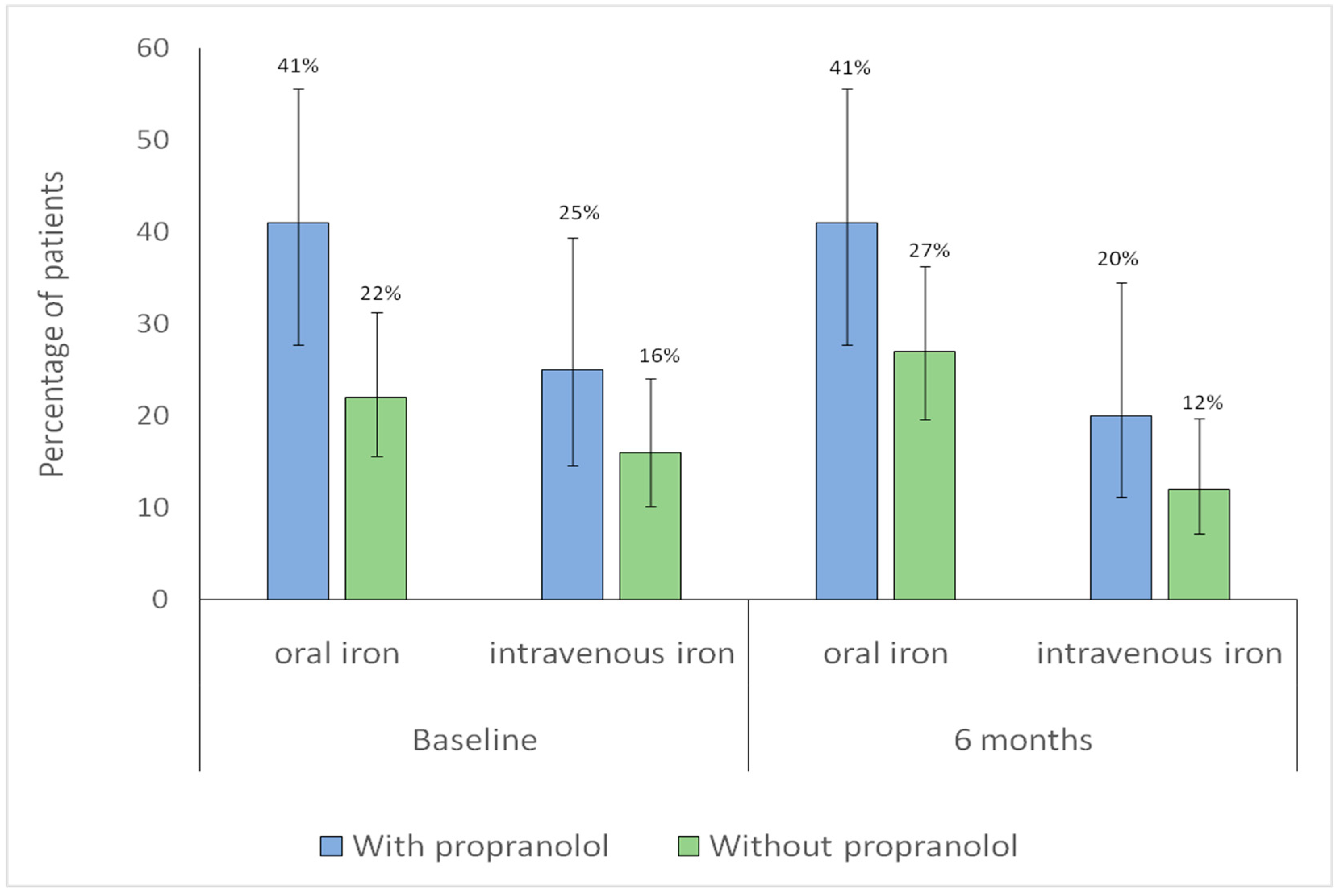

3.3. Hemoglobin and Iron Supplementation

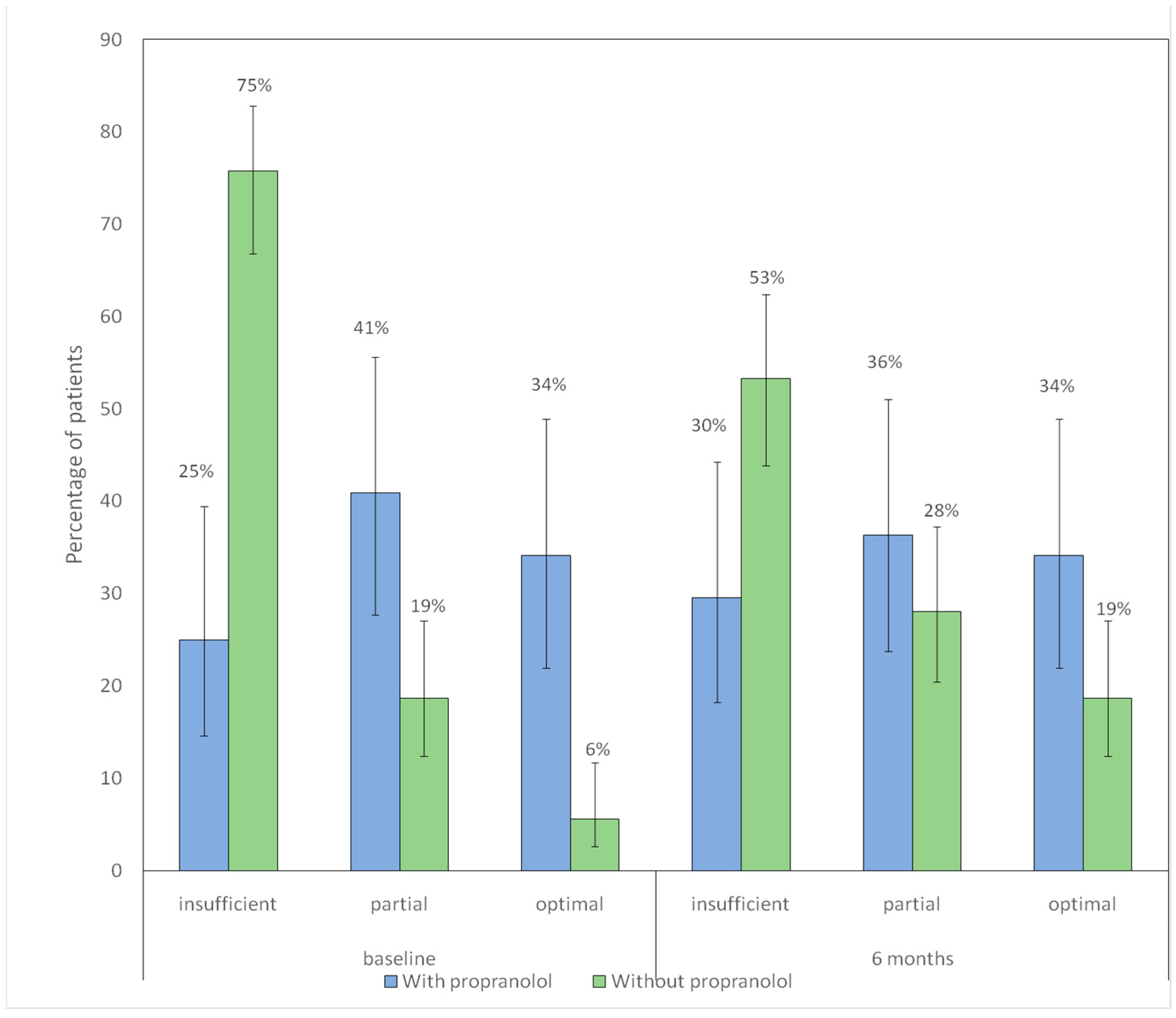

3.4. Nasal Care and Lubrication/Moisturizing

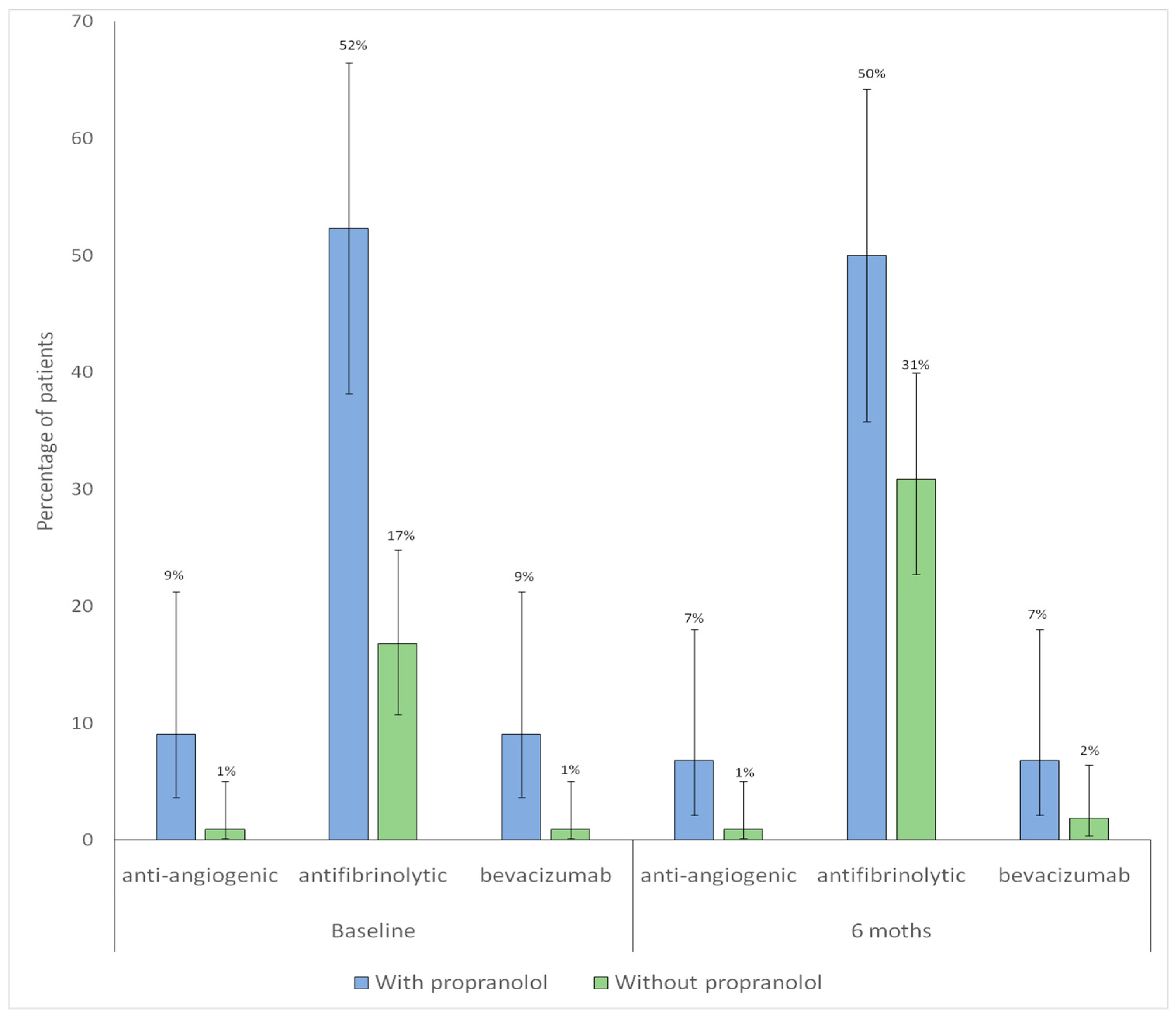

3.5. Pharmacological Treatments Other than Propranolol

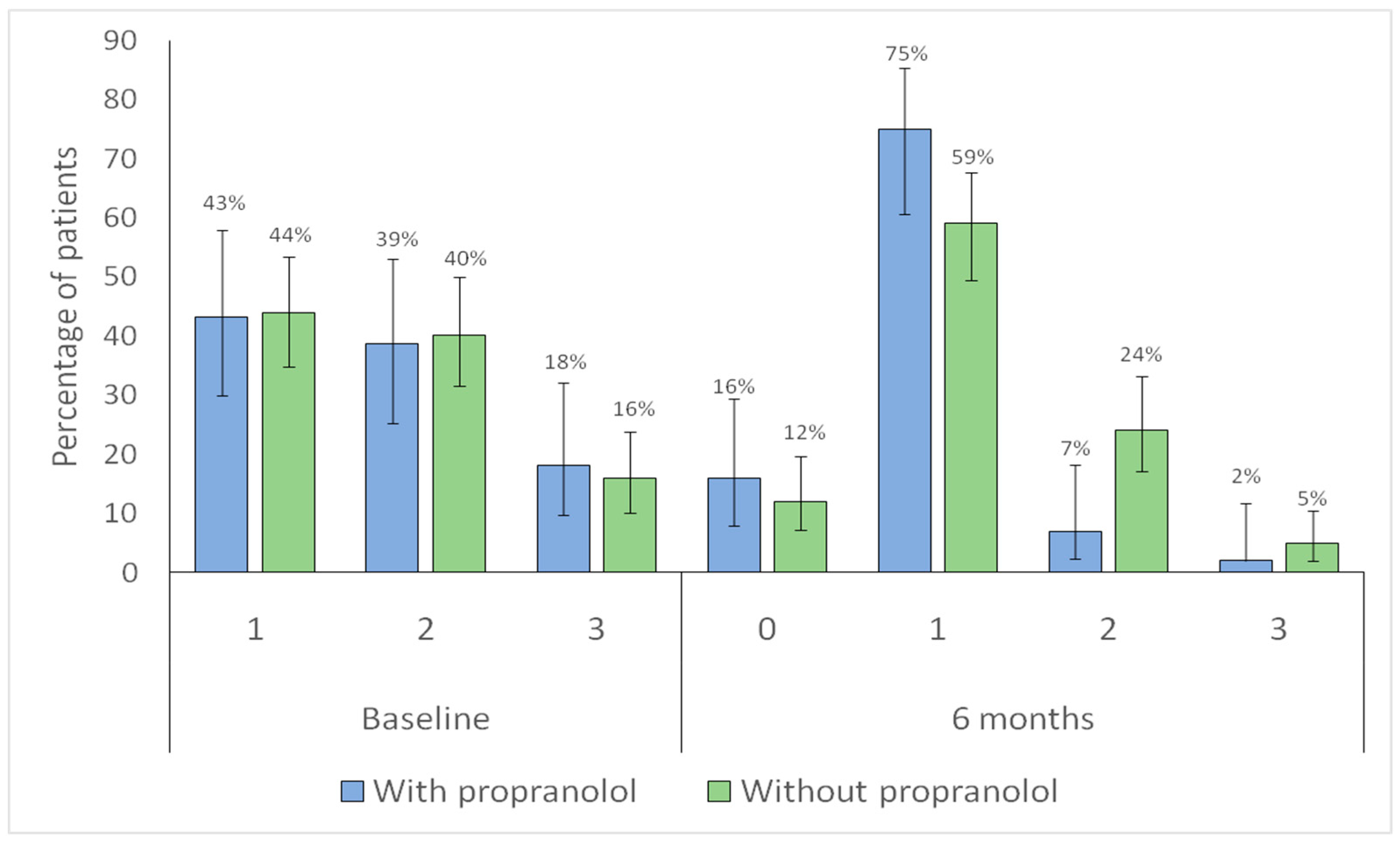

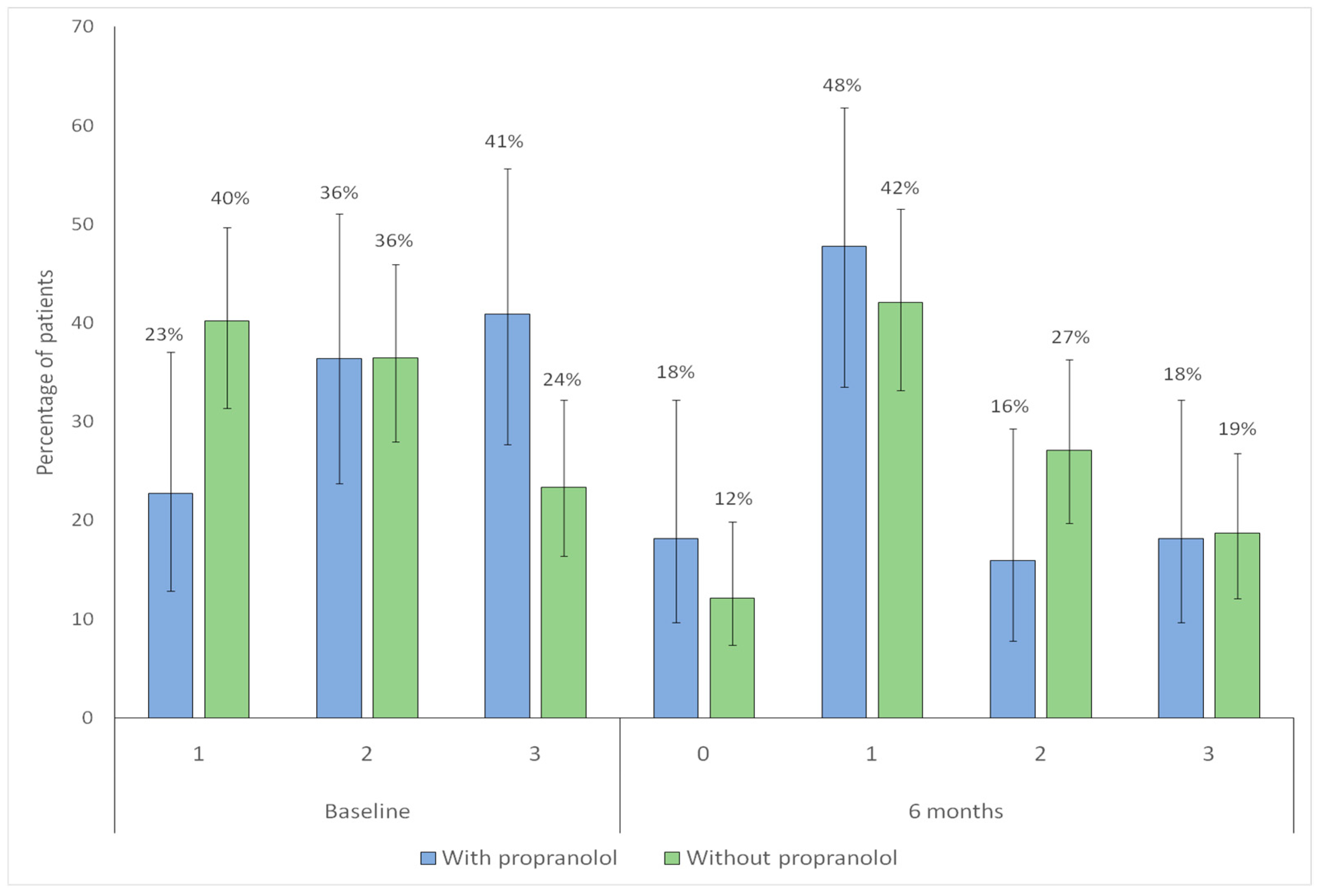

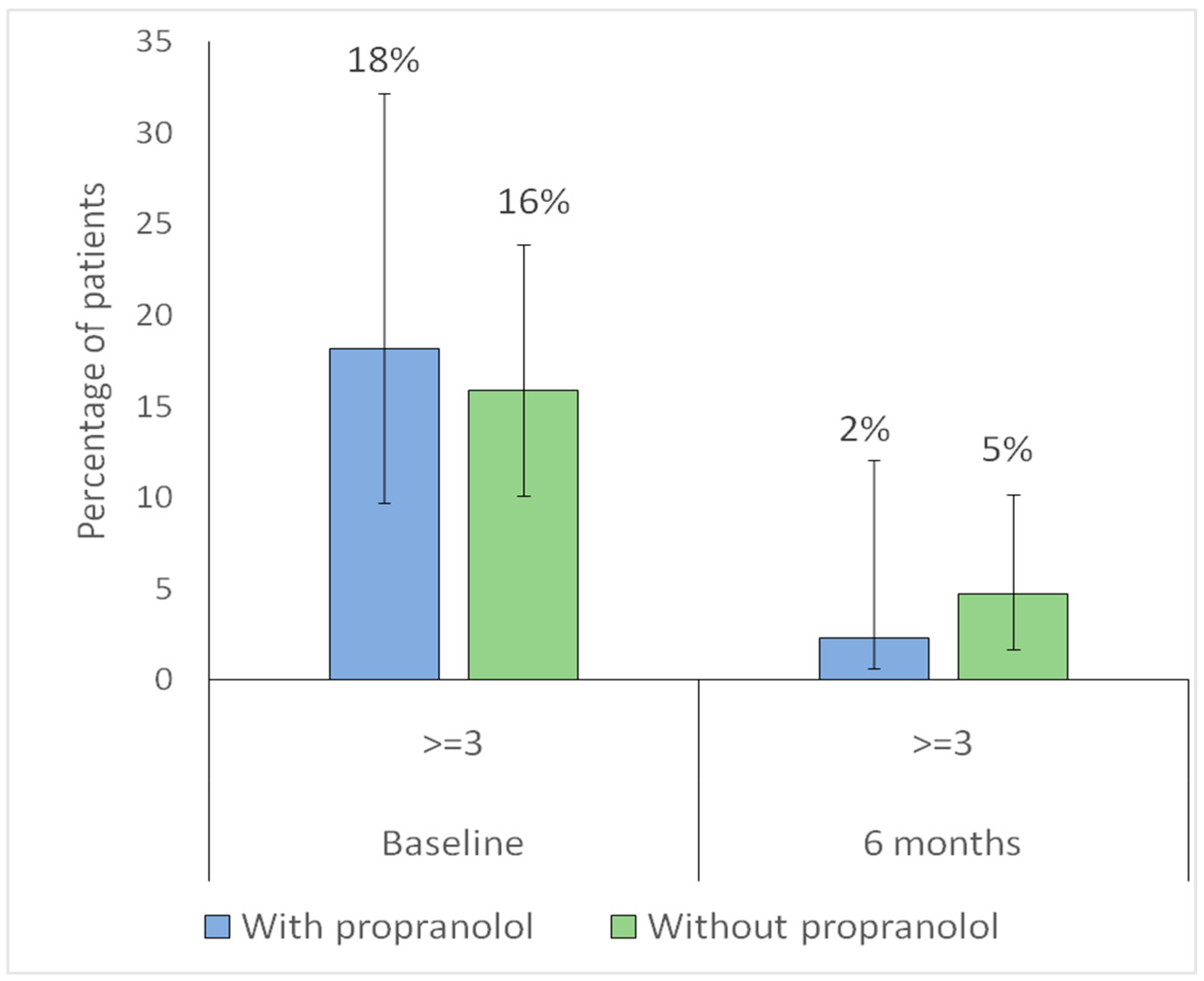

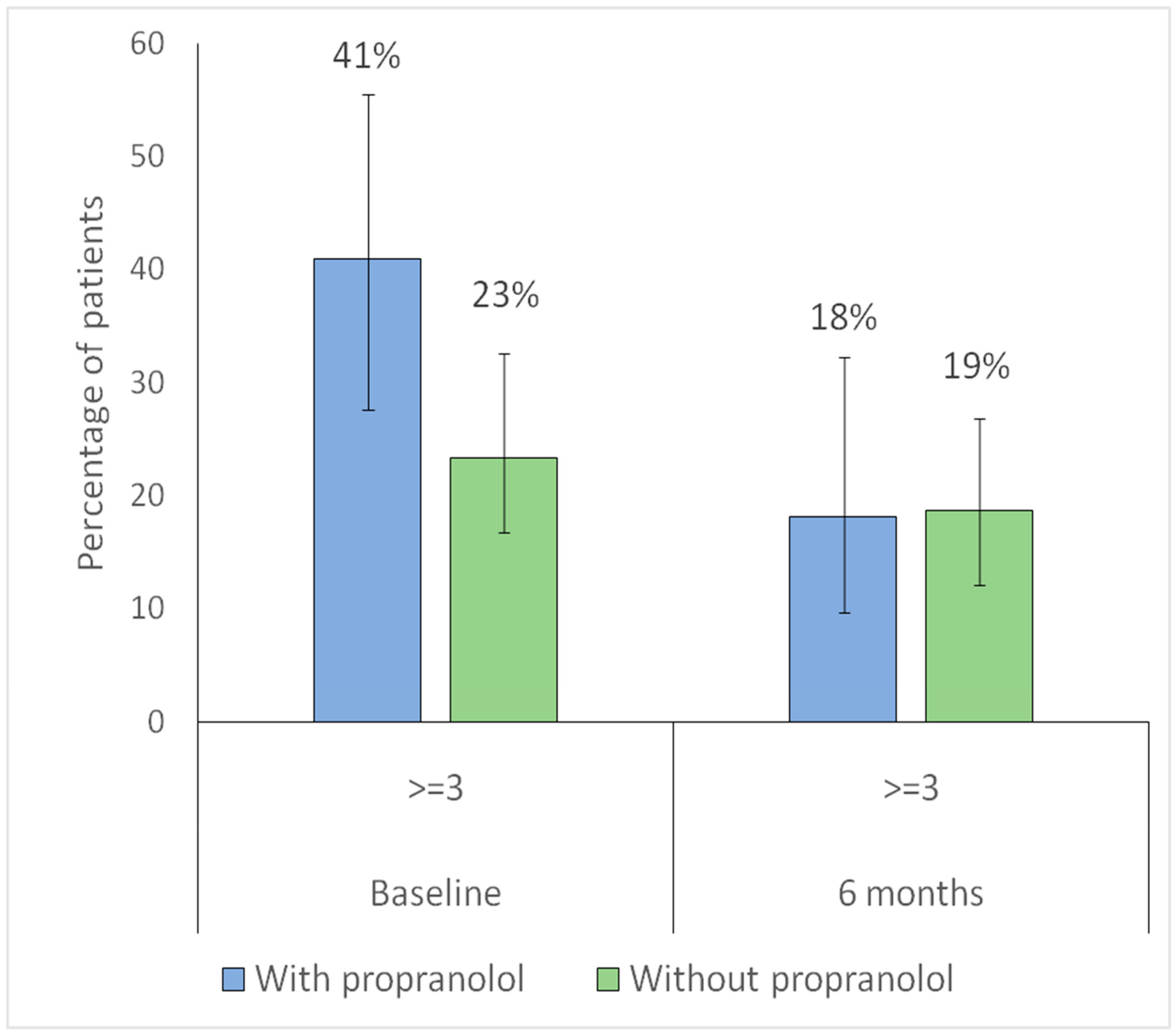

3.6. Association Between Propranolol Use and Improvement in Epistaxis

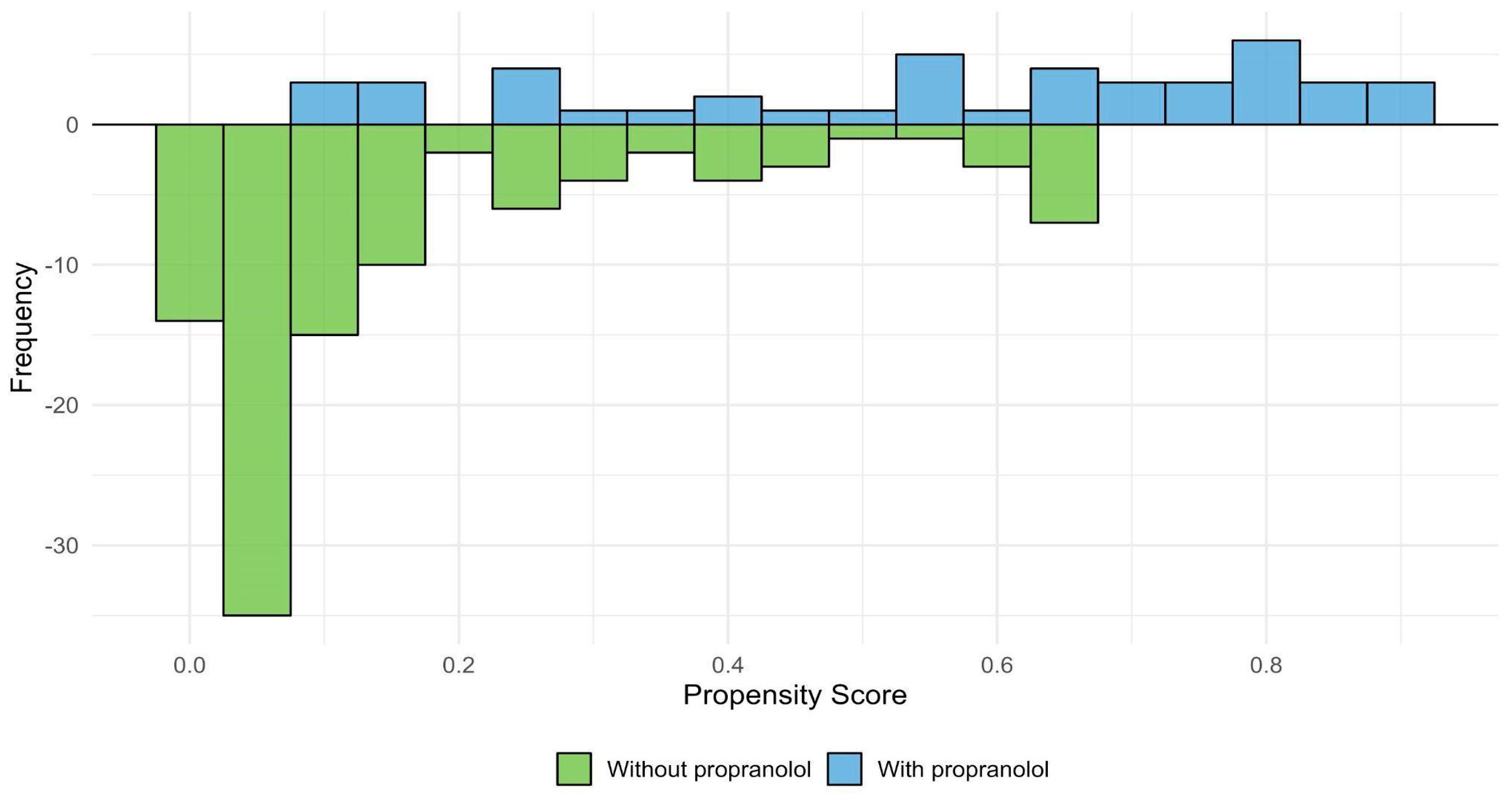

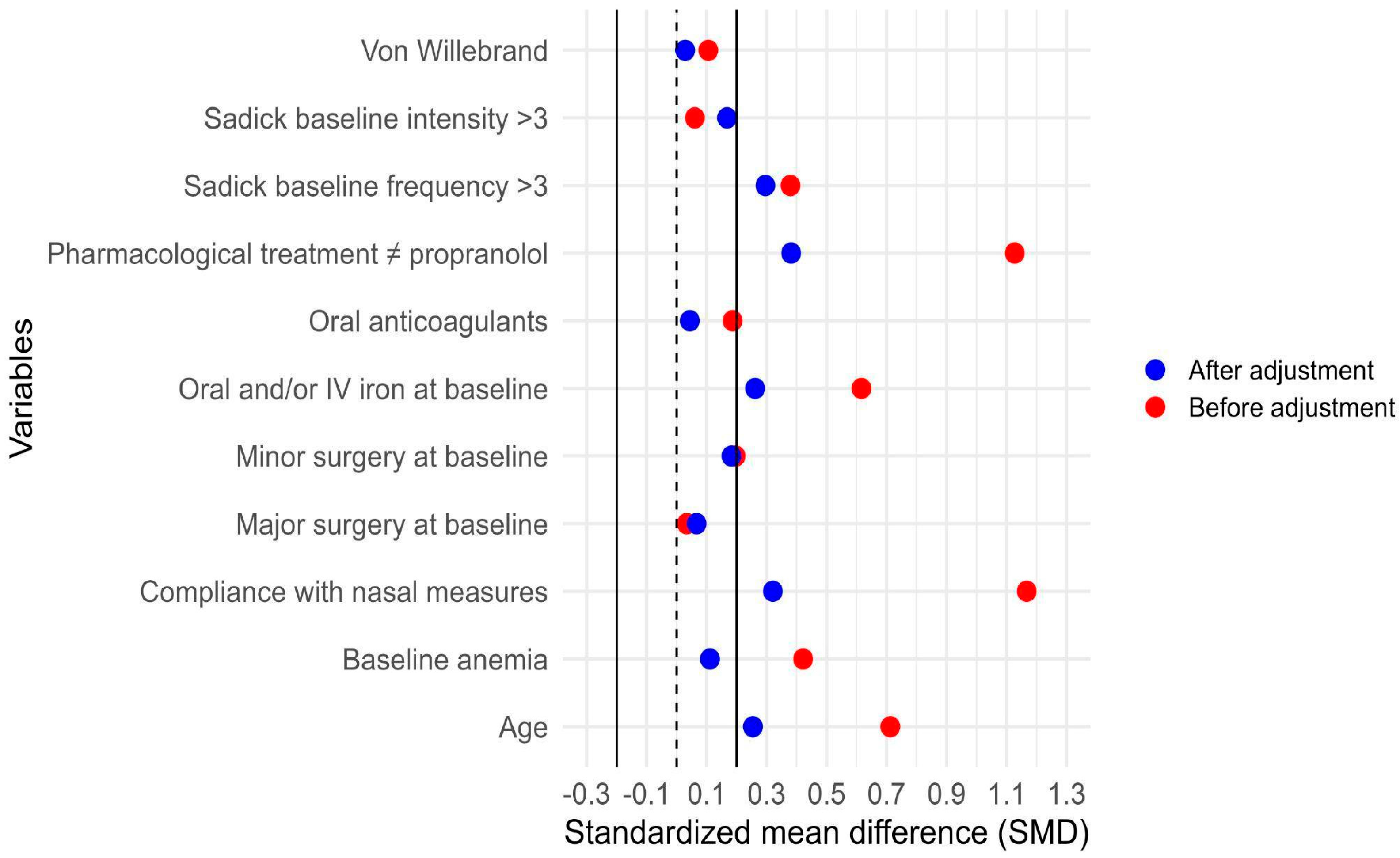

3.7. Adjustment for Indication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faughnan, M.E.; Palda, V.A.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Geisthoff, U.W.; McDonald, J.; Proctor, D.D.; Spears, J.; Brown, D.H.; Buscarini, E.; Chesnutt, M.S.; et al. International guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Med. Genet. 2011, 48, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, R.; Shovlin, C.L.; Kasthuri, R.S.; Serra, M.; Eker, O.F.; Bailly, S.; Buscarini, E.; Dupuis-Girod, S. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, M.m.; Papi, M.; Serrano, C. Prevalence of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in a medical care program organization in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Medicina 2024, 84, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen, A.D.; Vase, P.; Green, A. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: A population-based study of prevalence and mortality in Danish patients. J. Intern. Med. 1999, 245, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Llorente, L.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; Rossi, E.; Smadja, D.M.; Botella, L.M.; Bernabeu, C. Endoglin and alk1 as therapeutic targets for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasthuri, R.S.; Montifar, M.; Nelson, J.; Kim, H.; Lawton, M.T.; Faughnan, M.E. The Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium HHT Investigator Group. Prevalence and predictors of anemia in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, E591–E593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shovlin, C.L.; Guttmacher, A.E.; Buscarini, E.; Faughnan, M.E.; Hyland, R.H.; Westermann, C.J.; Kjeldsen, A.D.; Plauchu, H. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000, 91, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.; Bayrak-Toydemir, P.; DeMille, D.; Wooderchak-Donahue, W.; Whitehead, K. Curaçao diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is highly predictive of a pathogenic variant in ENG or ACVRL1 (HHT1 and HHT2). Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samkari, H. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Systemic therapies, guidelines, and an evolving standard of care. Blood 2021, 137, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrand, I.; Ingrand, P.; Gilbert-Dussardier, B.; Defossez, G.; Jouhet, V.; Migeot, V.; Dufour, X.; Klossek, J. Altered quality of life in Rendu-Osler-Weber disease related to recurrent epistaxis. Rhinology 2011, 49, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrabeitia, R.; Fariñas-Álvarez, C.; Santibáñez, M.; Señaris, B.; Fontalba, A.; Botella, L.M.; Parra, J.A. Quality of life in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, V.; Darby, Y.; Rimmer, J.; Amin, M.; Husain, S. Nasal closure for severe hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia in 100 patients. The Lund modification of the Young’s procedure: A 22-year experience. Rhinology 2017, 55, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faughnan, M.E.; Mager, J.J.; Hetts, S.W.; Palda, V.A.; Ratjen, F. Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1035–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mager, H.J.; Bernabeu, C.; Post, M. Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: Recent Advances and Future Challenges; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; 228p. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, F.; Desroches-Castan, A.; Bailly, S.; Dupuis-Girod, S.; Feige, J.-J. Future treatments for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, C.; Maurizi, N.; Marchionni, N.; Fornasari, D. β-blockers: Their new life from hypertension to cancer and migraine. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 151, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Léauté-Labrèze, C.; de la Roque, E.D.; Hubiche, T.; Boralevi, F.; Thambo, J.-B.; Taïeb, A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 2649–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sans, V.; de la Roque, E.D.; Berge, J.; Grenier, N.; Boralevi, F.; Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Lipsker, D.; Dupuis, E.; Ezzedine, K.; Vergnes, P.; et al. Propranolol for severe infantile hemangiomas: Follow-up report. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e423–e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, A.M.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; Casado-Vela, J.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Botella, L.-M.; Albiñana, V. The Role of Propranolol as a Repurposed Drug in Rare Vascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; de Rojas-P, I.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Aguado, T.; Canto-Cano, A.; Aguirre, D.T.; Serra, M.M.; González-Peramato, P.; Martínez-Piñeiro, L.; et al. Targeting β2-Adrenergic Receptors Shows Therapeutical Benefits in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma from Von Hippel-Lindau Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Zarrabeitia, R.; Bernabéu, C.; Botella, L.M. Propranolol as antiangiogenic candidate for the therapy of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Thromb. Haemost. 2012, 108, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contis, A.; Gensous, N.; Viallard, J.; Goizet, C.; Léauté-Labrèze, C.; Duffau, P. Efficacy and safety of propranolol for epistaxis in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: Retrospective, then prospective study, in a total of 21 patients. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2017, 42, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Casado, S.; Martín de Rosales Cabrera, A.M.; Usarralde Pérez, A.; Martínez Simón, J.J.; Zhan Zhou, E.; Marcos Salazar, M.S.; Encinas, M.P.; Cubells, L.B. Sclerotherapy and Topical Nasal Propranolol: An Effective and Safe Therapy for HHT-Epistaxis. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 2216–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, J.; Cervin, A.; Grigg, C.; Liu, Z.; Bates, J.; Brahmabhatt, P.; Girling, K.; Banks, A.; McCormack, L.; Walker, A.; et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral propranolol for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Aust. J. Otolaryngol. 2025, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergler, W.; Sadick, H.; Riedel, F.; Götte, K.; Hörmann, K. Topical estrogens combined with argon plasma coagulation in the management of epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2002, 111, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesnaye, N.C.; Stel, V.S.; Tripepi, G.; Dekker, F.W.; Fu, E.L.; Zoccali, C.; Jager, K.J. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, B.A.; Frommelt, P.C.; Chamlin, S.L.; Haggstrom, A.; Bauman, N.M.; Chiu, Y.E.; Chun, R.H.; Garzon, M.C.; Holland, K.E.; Liberman, L.; et al. Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: Report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Bernabeu-Herrero, M.E.; Zarrabeitia, R.; Bernabeu, C.; Botella, L.M. Estrogen therapy for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): Effects of raloxifene, on Endoglin and ALK1 expression in endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 103, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarki, H.; Rimmer, J. The Use of Beta-Blockers in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia-Related Epistaxis: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2022, 36, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorfer, K.E.; Seebauer, C.T.; Koller, M.; Zeman, F.; Berneburg, M.; Fischer, R.; Vielsmeier, V.; Bohr, C.; Kühnel, T.S. TIMolol nasal spray as a treatment for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT)—Study protocol of the prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled cross-over TIM-HHT trial. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2021, 80, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei-Zahav, M.; Gendler, Y.; Bruckheimer, E.; Prais, D.; Birk, E.; Watad, M.; Goldschmidt, N.; Soudry, E. Topical Propranolol Improves Epistaxis Control in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT): A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, C.; Gonzalez, M.L.; Ferraris, A.; Bandi, J.C.; Serra, M.M. Bevacizumab for treating Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia patients with severe hepatic involvement or refractory anemia. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parambil, J.G.; Gossage, J.R.; McCrae, K.R.; Woodard, T.D.; Menon, K.V.N.; Timmerman, K.L.; Pederson, D.P.; Sprecher, D.L.; Al-Samkari, H. Pazopanib for severe bleeding and transfusion-dependent anemia in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Angiogenesis 2022, 25, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Samkari, H. Systemic Antiangiogenic Therapies for Bleeding in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Practical, Evidence-Based Guide for Clinicians. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 48, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, K.; Kikuchi, H.; Imayoshi, S.; Dias, M.S. Topical application of timolol decreases the severity and frequency of epistaxis in patients who have previously undergone nasal dermoplasty for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Auris Nasus Larynx 2016, 43, 429–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei-Zahav, M.; Blau, H.; Bruckheimer, E.; Zur, E.; Goldschmidt, N. Topical propranolol improves epistaxis in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia—A preliminary report. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2017, 46, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis-Girod, S.; Pitiot, V.; Bergerot, C.; Fargeton, A.-E.; Beaudoin, M.; Decullier, E.; Bréant, V.; Colombet, B.; Philouze, P.; Faure, F.; et al. Efficacy of TIMOLOL nasal spray as a treatment for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, A.M.; Lee, J.J.; Kallogjeri, D.; Schneider, J.S.; Chakinala, M.M.; Piccirillo, J.F. Efficacy of Timolol in a Novel Intranasal Thermosensitive Gel for Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia-Associated Epistaxis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiñana, V.; Cuesta, A.M.; de Rojas-P, I.; Gallardo-Vara, E.; Recio-Poveda, L.; Bernabéu, C.; Botella, L.M. Review of Pharmacological Strategies with Repurposed Drugs for Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia Related Bleeding. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PhillPhillips, M.R.; Wykoff, C.C.; Thabane, L.; Bhandari, M.; Chaudhary, V. Retina Evidence Trials InterNational Alliance (R.E.T.I.N.A.) Study Group. The clinician’s guide to p values, confidence intervals, and magnitude of effects. Eye 2022, 36, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andorfer, K.E.C.; Zeman, F.; Koller, M.; Zeller, J.; Fischer, R.; Seebauer, C.T.; Vielsmeier, V.; Bohr, C.; Kühnel, T.S. TIMolol Nasal Spray as a Treatment for Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (TIM-HHT)-A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled, Cross-Over Trial. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, H.M.; Roman, B.L. An update on preclinical models of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: Insights into disease mechanisms. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 973964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaulanjan-Checkmodine, P.; Oucherif, S.; Prey, S.; Gontier, E.; Lacomme, S.; Loot, M.; Miljkovic-Licina, M.; Cario, M.; Léauté-Labrèze, C.; Taieb, A.; et al. Is Infantile Hemangioma a Neuroendocrine Tumor? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GaillGaillard, S.; Dupuis-Girod, S.; Boutitie, F.; Rivière, S.; Morinière, S.; Hatron, P.; Manfredi, G.; Kaminsky, P.; Capitaine, A.; Roy, P.; et al. Tranexamic acid for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia patients: A European cross-over controlled trial in a rare disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1494–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachetti, A.; Garcia-Monaco, R.; Sojo, M.; Scacchi, M.F.; Cernadas, C.; Lemcke, M.G.; Dovasio, F. Long-term treatment with oral propranolol reduces relapses of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epperla, N.; Brilliant, M.H.; Vidaillet, H. Topical timolol for treatment of epistaxis in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with bradycardia: A look at CYP2D6 metabolising variants. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, 2014, bcr2013203056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Excluded n = 201 | Included n = 151 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender n (%) | 0.902 | ||

| Male | 77 (38.3) | 56 (37.1) | |

| Female | 124 (61.7) | 95 (62.9) | |

| Median Age (IQR) | 43 (34–58) | 50 (38.5–64) | 0.003 |

| Place of origin n (%) | 0.074 | ||

| Buenos Aires City | 61 (30.3) | 61 (40.4) | |

| Greater Buenos Aires | 49 (24.4) | 42 (27.8) | |

| Province of Buenos Aires | 32 (15.9) | 16 (10.6) | |

| Other Provinces | 59 (29.4) | 32 (21.2) | |

| Residency outside of the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, n (%) | 0.014 | ||

| Yes | 91 (45.3) | 48 (31.8) | |

| No | 110 (54.7) | 103 (68.2) |

| Grade of Sadick–Bergler | Frequency of Bleeding | Intensity of Bleeding |

|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Less than once per week | Slight stains on handkerchief |

| Grade 2 | Several times per week | Soaked handkerchief |

| Grade 3 | More than once per day | Bowl or equivalent container necessary |

| Excluded (n = 201) | Included (n = 151) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender n (%) | 0.902 | ||

| Female, n (%) | 124 (61.7) | 95 (62.9) | |

| Male, n (%) | 77 (38.3) | 56 (37.1) | |

| Median age (IQR) | 43 (34–58) | 50 (38.5–64) | 0.003 |

| AVMs, n (%) | 106 (52.7) | 124 (82.1) | <0.001 |

| Sadick–Bergler scale Intensity * n (%) | |||

| 1 | 115 (57.2) | 84 (55.6) | |

| 2 | 63 (31.3) | 50 (33.1) | 0.939 |

| 3 | 23 (11.4) | 17 (11.3) | |

| Sadick–Bergler scale Frequency * n (%) | |||

| 1 | 102 (50.7) | 70 (46.4) | |

| 2 | 46 (22.9) | 25 (29.8) | 0.341 |

| 3 | 53 (26.4) | 36 (23.8) | |

| Sadick–Bergler scale ** | |||

| Intensity ≥ 3 | 53 (26.4) | 36 (23.8) | 0.677 |

| Frequency ≥ 3 | 23 (11.4) | 17 (11.3) | 0.999 |

| Characteristic | Without Propranolol (n = 107) | With Propranolol (n = 44) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 47 (34–62.5) | 62 (48.7–68) | <0.001 |

| Gender female, n (%) | 68 (63.6) | 27 (61.4) | 0.946 |

| HMO, n (%) | 19 (17.8) | 3 (6.8) | 0.140 |

| Argentine nationality, n (%) | 102 (95.3) | 43 (97.7) | 0.820 |

| Vascular malformations, n (%) | |||

| CNS involvement | 22 (20.6) | 14 (31.8) | 0.206 |

| Hepatic involvement | 72 (67.3) | 38 (86.4) | 0.028 |

| Pulmonary involvement | 47 (43.9) | 17 (38.6) | 0.677 |

| Digestive involvement | 13 (12.1) | 12 (27.3) | 0.042 |

| Any visceral involvement #1 | 92 (86) | 39 (88.6) | 0.862 |

| Hemorrhagic conditions or comorbidities, n (%) #2,** | |||

| Von Willebrand disease | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.3) | 0.999 |

| Anticoagulant use * | 3 (2.8) | 3 (6.8) | 0.491 |

| Specific treatments for HHT other than propranolol, n (%) | |||

| Antifibrinolytics | 18 (16.8) | 23 (52.3) | <0.001 |

| Hormonal therapy or analogs | 5 (4.7) | 8 (18.2) | 0.018 |

| Bevacizumab | 1 (0.9) | 4 (9.1) | 0.041 |

| Other antiangiogenic agents #3 | 1 (0.9) | 4 (9.1) | 0.041 |

| At least one non-propranolol drug #4 | 25 (23.4) | 32 (72.7) | <0.001 |

| Compliance with nasal hygiene and lubrication measures, n (%) * | |||

| Insufficient | 81 (75.7) | 11 (25) | |

| Partial compliance | 20 (18.7) | 18 (40.9) | <0.001 |

| Optimal compliance | 6 (5.6) | 15 (34.1) | |

| Non-compliance with nasal hygiene/lubrication #5,** | 81 (88) | 11 (11.9) | 0.001 |

| Baseline surgical or ablative treatments, n (%) | |||

| Major surgery | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.3) | 0.999 |

| Young’s procedure | 0 | 2 (4.5) | 0.151 |

| Minor surgery | 10 (9.3) | 7 (15.9) | 0.381 |

| Iron support and/or transfusions, n (%) | |||

| Oral iron | 24 (22.4) | 18 (40.9) | 0.035 |

| Intravenous iron | 17 (15.9) | 11 (25) | 0.281 |

| Oral and/or intravenous iron | 34 (31.8) | 27 (61.4) | 0.001 |

| RBC transfusions | 5 (4.7) | 1 (2.3) | 0.820 |

| Baseline hemoglobin | |||

| Mean hemoglobin (SD) | 12.1 (2.2) | 11.1 (2.1) | 0.007 |

| Anemia #6 n (%) | 51 (47.7) | 30 (68.2) | 0.034 |

| Sadick–Bergler scale Intensity * n (%) | |||

| 1 | 47(43.9) | 19 (43.2) | |

| 2 | 43 (40.2) | 17 (38.6) | 0.941 |

| 3 | 17 (15.9) | 8 (18.2) | |

| Sadick–Bergler scale Frequency * n (%) | |||

| 1 | 43 (40.2) | 10 (22.7) | |

| 2 | 39 (36.4) | 16 (36.4) | 0.048 |

| 3 | 25 (23.4) | 18 (40.9) | |

| Sadick–Bergler scale ** n (%) | |||

| Sadick–Bergler intensity ≥ 3 | 17 (15.9) | 8 (18.2) | 0.917 |

| Sadick–Bergler frequency ≥ 3 | 25 (23.4) | 18 (40.9) | 0.049 |

| Digestive bleeding baseline (%) | 12 (25) | 8 (25) | 0.993 |

| Digestive bleeding at 6 months, n (%) | 9 (18.8) | 8 (25) | 0.516 |

| Epistaxis Improvement | Cr OR (CI 95%) | p Value | Adj OR (CI 95%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without propranolol | reference | |||

| With propranolol | 2.2 (0.9–5.6) | 0.079 | 2.8 (0.9–8.6) | 0.083 |

| Epistaxis Improvement | Cr OR (CI 95%) | p Value | Adj OR (CI 95%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | ||||

| Without propranolol | reference | |||

| With propranolol | 1.5 (0.7–2.9) | 0.286 | 1.9 (0.7–5.2) | 0.181 |

| Frequency | ||||

| Without propranolol | reference | |||

| With propranolol | 2.9 (1.4–5.9) | 0.004 | 3.8 (1.3–11.2) | 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Serra, M.M.; Pagotto, V.; Botella, L.M.; Bernabeu, C. Propranolol Reduces Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Large Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010372

Serra MM, Pagotto V, Botella LM, Bernabeu C. Propranolol Reduces Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Large Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010372

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerra, Marcelo Martín, Vanina Pagotto, Luisa Maria Botella, and Carmelo Bernabeu. 2026. "Propranolol Reduces Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Large Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010372

APA StyleSerra, M. M., Pagotto, V., Botella, L. M., & Bernabeu, C. (2026). Propranolol Reduces Epistaxis in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: A Large Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 372. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010372