Does Further Lowering Intraoperative Intraocular Pressure Reduce Surgical Invasiveness in Active-Fluidics Eight-Chop Phacoemulsification? A Fellow-Eye Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Preoperative Assessment

2.4. Active Fluidics System and Intraoperative IOP Settings

2.5. Surgical Technique

2.6. Outcome Measures

2.6.1. Aqueous Flare

2.6.2. Corneal Endothelial Cell Density

2.6.3. Corneal Morphological Parameters

2.6.4. Intraocular Pressure

2.6.5. Best-Corrected Visual Acuity

2.6.6. Intraoperative Parameters

2.7. Sample Size Considerations

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.8.1. Modeling Approach

2.8.2. Handling of Missing Data

2.8.3. Analysis of Corneal Endothelial Cell Density Loss

2.8.4. Analysis of Preoperative Characteristics

2.8.5. Visual Acuity Analysis

2.8.6. Significance Threshold

2.9. GenAI Statement

3. Results

3.1. Preoperative Characteristics

3.2. Intraoperative Parameters

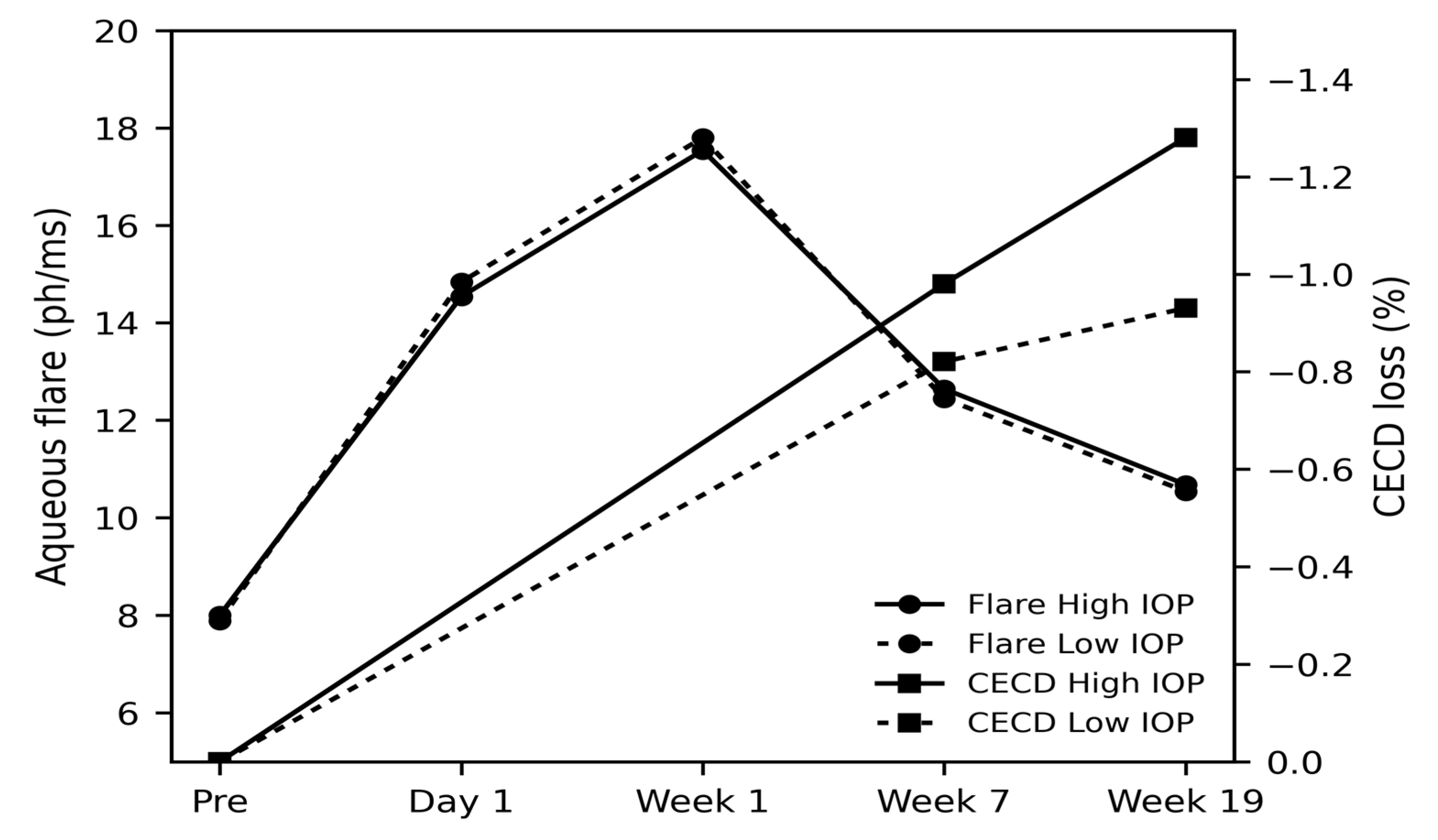

3.3. Postoperative Flare and Corneal Endothelial Outcomes

3.4. Corneal Morphological Parameters

3.5. Postoperative Intraocular Pressure

3.6. Best-Corrected Visual Acuity

3.7. Intraoperative Stability at Low IOP

3.8. Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFS | Active Fluidics System |

| ASM | Active Surge Mitigation |

| CCT | Central corneal thickness |

| CDE | Cumulative dissipated energy |

| CECD | Corneal endothelial cell density |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| GFS | Gravity-based fluidics system |

| IOP | Intraocular pressure |

| PHC | Percentage of hexagonal cells |

References

- Kelman, C.D. Phaco-emulsification and aspiration. A new technique of cataract removal. A preliminary report. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1967, 64, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulter, T.; Bernhisel, A.; Mamalis, C.; Zaugg, B.; Barlow, W.R.; Olson, R.J.; Pettey, J.H. Phacoemulsification in review: Optimization of cataract removal in an in vitro setting. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2019, 64, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, V.; Raj, S.M.; Praveen, M.R.; Vasavada, A.R.; Henderson, B.A.; Asnani, P.K. Real-time dynamic intraocular pressure fluctuations during microcoaxial phacoemulsification using different aspiration flow rates and their impact on early postoperative outcomes: A randomized clinical trial. J. Refract. Surg. 2014, 30, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, K.D.; Lorente, R.; Fanney, D.; Cionni, R.J. Clinical study using a new phacoemulsification system with surgical intraocular pressure control. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, M.P.; Joiner, H.; Kohler, R.A.; O’Connor, S. Phacoemulsification using an active fluidics system at physiologic vs high intraocular pressure: Impact on anterior and posterior segment physiology. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2024, 50, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; Gao, Y.; Ma, T.; Ye, Z.; Li, Z. A prospective randomized clinical trial of active-fluidics versus gravity-fluidics system in phacoemulsification for age-related cataract (AGSPC). Ann. Med. 2022, 54, 1977–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, J.; Hall, B. Efficiency of phacoemulsification handpieces with high and low intraocular pressure settings. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2025, 51, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T. Efficacy and safety of the eight-chop technique in phacoemulsification for patients with cataract. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2023, 49, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, J.M.; Little, J.H. Patient selection. In Phacoemulsification and Aspiration of Cataracts: Surgical Techniques, Complications, and Results; Emery, J.M., Little, J.H., Eds.; CV Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1979; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hong, J.; Chen, X. Comparisons of the clinical outcomes of Centurion® active fluidics system with a low IOP setting and gravity fluidics system with a normal IOP setting for cataract patients with low corneal endothelial cell density. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1294808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarey, B.E.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Lynn, M.J. Review of corneal endothelial specular microscopy for FDA clinical trials of refractive procedures, surgical devices, and new intraocular drugs and solutions. Cornea 2008, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wavikar, C.M.; Tanna, M.N.; Wavikar, G.C.; Kale, C.B.; Setia, M.S. Comparison of Post-Operative Outcomes between IOP-20 and IOP-50 in Phacoemulsification with Active Fluidics System: Randomized Single Blinded Trial. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 3573–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, X. Surgical outcomes of phacoemulsification with different fluidics systems (centurion with active sentry vs. centurion gravity) in cataract patients with eye axial length above 26 mm. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1554832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biljana, K.E.; Tea, Š.; Iva, Ć.; Benedict, R.; Dora, M.; Mladen, B.; Mirjana, B. Unraveling Active Surge Mitigation (ASM) Actuation: Optimizing Phacoemulsification with Active Sentry Handpiece. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 39, 392–398. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.J.; Kuo, A.F.; Olson, R.J. The risk of capsular breakage from phacoemulsification needle contact with the lens capsule: A laboratory study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 149, 882–886.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Oki, K.; Shiwa, T.; Oharazawa, H.; Takahashi, H. Effect of bottle height on the corneal endothelium during phacoemulsification. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2009, 35, 2014–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzmann, B.C.; Wenzel, D.A.; Bartz-Schmidt, K.U.; Spitzer, M.S.; Schultheiss, M. Effects of ultrasound energy on the porcine corneal endothelium—Establishment of a phacoemulsification damage model. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, e155–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; An, Q.; Zhou, H.; Ge, H. Research progress on the impact of cataract surgery on corneal endothelial cells. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2024, 4, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.K.; Chang, H.S.; Kim, M.S. Risk factors for endothelial cell loss after phacoemulsification: Comparison in different anterior chamber depth groups. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 24, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, H.; Ma, T.; Ye, Z.; Li, Z. Application of the Active-Fluidics System in Phacoemulsification: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Tao, J.; Yu, X.; Diao, W.; Bai, H.; Yao, L. Safety and prognosis of phacoemulsification using active sentry and active fluidics with different IOP settings—A randomized, controlled study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, V.; Agrawal, D.; Vasavada, S.A.; Vasavada, A.R.; Yagnik, J. Intraoperative Performance and Early Postoperative Outcomes Following Phacoemulsification with Three Fluidic Systems: A Randomized Trial. J. Refract. Surg. 2024, 40, e304–e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, M.; Cakir, G.Y.; Koser, E.; Altan, C.; Taşkapılı, M. Quantitative evaluation of inflammation after phacoemulsification surgery: Anterior chamber flare and choroidal vascular index. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 69, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, C.; Swampillai, A.J.; Lim, K.S.; Nanavaty, M.A. Factors influencing aqueous flare after cataract surgery and its evaluation with laser flare photometry. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2023, 15, 25158414231204111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Mi, L.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, W. Subfoveal Choroidal Thickness After Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery for Age-Related Cataracts. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 826042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opala, A.; Kołodziejski, Ł.; Grabska-Liberek, I. Impact of Well-Controlled Type 2 Diabetes on Corneal Endothelium Following Cataract Surgery: A Prospective Longitudinal Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Sharma, P.; Chouhan, J.K.; Goyal, R. Comparative evaluation of modified crater (endonucleation) chop and conventional crater chop techniques during phacoemulsification of hard nuclear cataracts: A randomized study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T. Minimizing Endothelial Cell Loss in Hard Nucleus Cataract Surgery: Efficacy of the Eight-Chop Technique. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poley, B.J.; Lindstrom, R.L.; Samuelson, T.W.; Schulze, R., Jr. Intraocular pressure reduction after phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes: Evaluation of a causal relationship between the natural lens and open-angle glaucoma. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2009, 35, 1946–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Roman, J.; Lazcano-Gomez, G.; Martínez-Baez, K.; Turati, M.; Gulías-Cañizo, R.; Hernández-Zimbrón, L.F.; Ochoa-De la Paz, L.; Zamora, R.; Gonzalez-Salinas, R. Effect of phacoemulsification on intraocular pressure in patients with primary open angle glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 10, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.; Das, M.; Sen, S. Comparative Analysis of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Manual Small-Incision Cataract Surgery Versus Phacoemulsification for Brown Cataracts. Cureus 2024, 16, e75260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, L. Modern cataract surgery with simplified technology: New trend? J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2025, 51, 353–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianchulev, S.; Yeu, E.; Hu, E.H.; Kamthan, G.; Pantanelli, S.; Singh, P.; Tyson, F. Micro-interventional pre-treatment for nucleus disassembly in the setting of non-cavitating sonic lensectomy: Real-world evidence study in 512 cases. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, N.T.; Scruggs, K.; Pantanelli, S.M. A Prospective Single-Center Clinical Trial Comparing Short-Term Outcomes of a Novel Non-Cavitating Handheld Lensectomy Device versus Phacoemulsification. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 2281–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | High IOP (n = 56) | Low IOP (n = 56) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73.4 ± 7.14 | 73.4 ± 7.14 | N/A |

| Sex (M/F) | 20/36 | 20/36 | N/A |

| Axial length (mm) | 24.1 ± 1.59 | 24.1 ± 1.64 | 0.943 |

| Anterior chamber depth (mm) | 3.21 ± 0.33 | 3.21 ± 0.35 | 0.664 |

| Nucleus grade | 2.27 ± 0.38 | 2.27 ± 0.36 | 0.844 |

| CECD (cells/mm2) | 2672 ± 235 | 2683 ± 228 | 0.449 |

| CV (%) | 38.9 ± 5.30 | 39.1 ± 5.75 | 0.663 |

| PHC (%) | 45.1 ± 7.50 | 45.4 ± 7.55 | 0.608 |

| CCT (µm) | 530 ± 38.0 | 530 ± 39.6 | 0.821 |

| Preoperative IOP (mmHg) | 13.4 ± 1.84 | 13.5 ± 1.60 | 0.623 |

| Preoperative flare (ph/ms) | 8.00 ± 2.63 Median 7.45 [6.4–8.8] | 7.89 ± 2.22 Median 7.8 [6.0–9.2] | 0.756 |

| Parameter | High IOP (n = 56) | Low IOP (n = 56) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (min) | 4.82 ± 1.13 | 5.08 ± 1.10 | 0.082 |

| Phaco time (s) | 13.9 ± 4.40 | 16.2 ± 5.22 | 0.001 |

| Aspiration time (s) | 69.0 ± 17.9 | 75.0 ± 18.3 | 0.033 |

| CDE | 5.56 ± 1.9 | 5.93 ± 1.87 | 0.099 |

| Irrigation volume (mL) | 25.2 ± 7.35 | 26.6 ± 7.71 | 0.214 |

| Parameter | High IOP | Low IOP | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flare (ph/ms)—Preoperative | 8.00 ± 2.63 (n = 54) | 7.89 ± 2.22 (n = 55) | 0.756 |

| Flare (ph/ms)—Day 1 | 14.54 ± 4.76 (n = 53) | 14.84 ± 5.10 (n = 55) | 0.655 |

| Flare (ph/ms)—Week 1 | 17.54 ± 7.67 (n = 54) | 17.80 ± 8.18 (n = 55) | 0.820 |

| Flare (ph/ms)—Week 7 | 12.64 ± 3.93 (n = 51) | 12.44 ± 3.93 (n = 51) | 0.700 |

| Flare (ph/ms)—Week 19 | 10.68 ± 2.41 (n = 44) | 10.54 ± 2.12 (n = 44) | 0.749 |

| CECD loss (%)—Week 7 | −0.98 ± 1.16 (n = 49) | −0.82 ± 1.05 (n = 49) | 0.460 |

| CECD loss (%)—Week 19 | −1.28 ± 1.69 (n = 41) | −0.93 ± 1.38 (n = 41) | 0.239 |

| Parameter | Time Point | High IOP (Mean ± SD) | Low IOP (Mean ± SD) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCT (µm) | Preoperative | 529.9 ± 38.0 (n = 56) | 530.3 ± 39.6 (n = 56) | 0.821 |

| CCT (µm) | Week 7 | 529.9 ± 39.8 (n = 49) | 528.2 ± 40.6 (n = 49) | 0.410 |

| CCT (µm) | Week 19 | 530.4 ± 37.1 (n = 41) | 530.6 ± 38.4 (n = 41) | 0.942 |

| CV (%) | Preoperative | 38.9 ± 5.3 (n = 56) | 39.1 ± 5.7 (n = 56) | 0.663 |

| CV (%) | Week 7 | 38.7 ± 6.0 (n = 49) | 38.0 ± 5.1 (n = 49) | 0.190 |

| CV (%) | Week 19 | 38.5 ± 4.9 (n = 41) | 38.0 ± 4.5 (n = 41) | 0.386 |

| PHC (%) | Preoperative | 45.1 ± 7.5 (n = 56) | 45.4 ± 7.6 (n = 56) | 0.608 |

| PHC (%) | Week 7 | 45.9 ± 8.0 (n = 49) | 46.5 ± 6.6 (n = 49) | 0.389 |

| PHC (%) | Week 19 | 46.0 ± 6.1 (n = 41) | 46.6 ± 6.2 (n = 41) | 0.459 |

| Time Point | Setting | n | Mean ± SD (mmHg) | % Change | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative IOP | High | 56 | 13.37 ± 1.84 | N/A | 0.623 |

| Preoperative IOP | Low | 55 | 13.44 ± 1.60 | N/A | |

| 7 weeks postoperative | High | 51 | 12.19 ± 1.69 | −8.8% | 0.836 |

| 7 weeks postoperative | Low | 51 | 12.22 ± 1.55 | −9.1% | |

| 19 weeks postoperative | High | 43 | 12.42 ± 1.97 | −7.1% | 0.528 |

| 19 weeks postoperative | Low | 43 | 12.29 ± 1.87 | −8.6% |

| Time Point | High IOP (Mean ± SD) | Low IOP (Mean ± SD) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | 0.097 ± 0.214 (n = 56) | 0.113 ± 0.131 (n = 56) | 0.597 |

| Week 7 | −0.069 ± 0.029 (n = 51) | −0.071 ± 0.022 (n = 51) | 0.644 |

| Week 19 | −0.072 ± 0.024 (n = 43) | −0.068 ± 0.028 (n = 43) | 0.336 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sato, T. Does Further Lowering Intraoperative Intraocular Pressure Reduce Surgical Invasiveness in Active-Fluidics Eight-Chop Phacoemulsification? A Fellow-Eye Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010366

Sato T. Does Further Lowering Intraoperative Intraocular Pressure Reduce Surgical Invasiveness in Active-Fluidics Eight-Chop Phacoemulsification? A Fellow-Eye Comparative Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010366

Chicago/Turabian StyleSato, Tsuyoshi. 2026. "Does Further Lowering Intraoperative Intraocular Pressure Reduce Surgical Invasiveness in Active-Fluidics Eight-Chop Phacoemulsification? A Fellow-Eye Comparative Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010366

APA StyleSato, T. (2026). Does Further Lowering Intraoperative Intraocular Pressure Reduce Surgical Invasiveness in Active-Fluidics Eight-Chop Phacoemulsification? A Fellow-Eye Comparative Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010366