The Transforming Growth Factor β Genes and Susceptibility to Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Physically Active Caucasian Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Participants

2.3. DNA Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

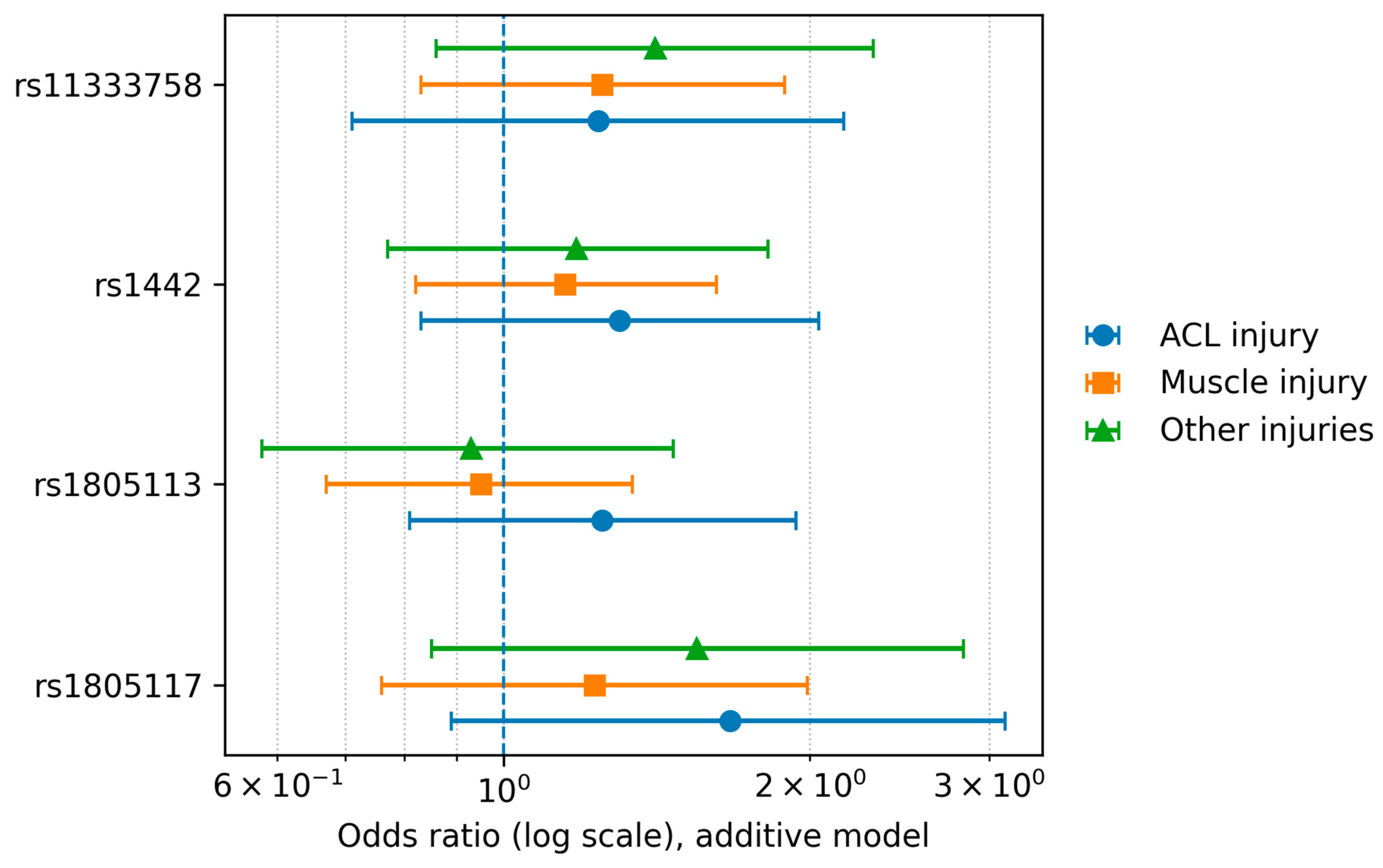

3.1. Individual SNP Analysis

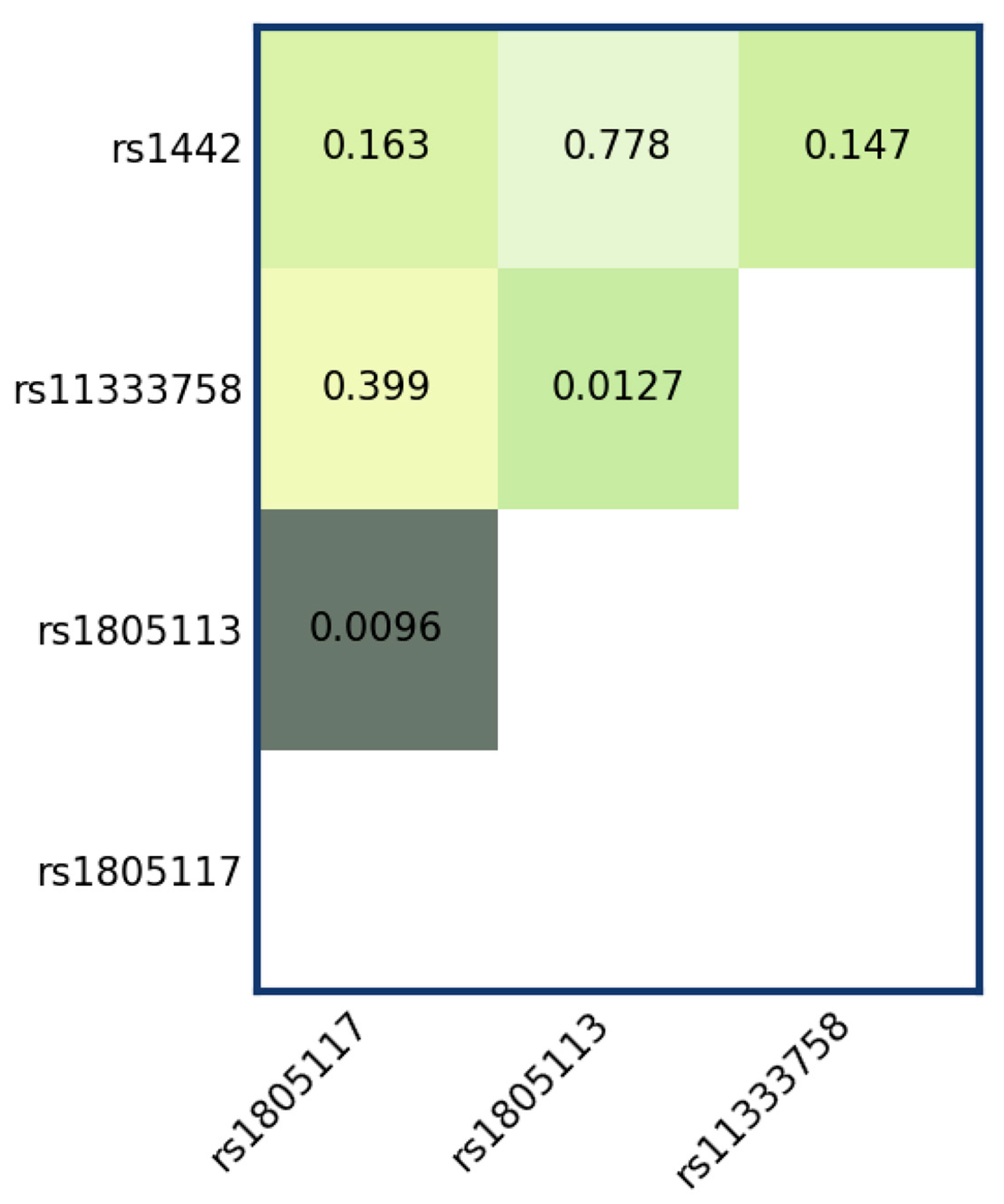

3.2. Epistasis Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3′UTR | 3′ Untranslated Region |

| ACL | Anterior Cruciate Ligament |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BMPs | Bone Morphogenetic Proteins |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CTGF | Connective Tissue Growth Factor |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ECM | Muscle Extracellular Matrix |

| EM | Expectation-Maximization algorithm |

| GDF-8 | Growth Differentiation Factor 8 |

| GDFs | Growth and Differentiation Factors |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| GRCh38 | Genome Reference Consortium Human build 38 |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| LTR | Log-Likelihood Ratio Test |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MSTN | Myostatin |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| STREGA | STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association studies |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-Beta |

| TGFBI | Transforming Growth Factor Beta Induced |

| TGFBR3 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor 3 |

References

- Gumucio, J.P.; Sugg, K.B.; Mendias, C.L. TGF-β Superfamily Signaling in Muscle and Tendon Adaptation to Resistance Exercise. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2015, 43, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.J. Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-β superfamily member. Nature 1997, 387, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, M.; Derynck, R.; Miyazono, K. TGF- β and the TGF-β family: Context-dependent roles in cell and tissue physiology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a021873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo, C.; Beanes, S.R.; Hu, F.Y.; Zhang, X.; Dang, C.; Chang, G.; Wang, Y.; Nishimura, I.; Freymiller, E.; Longaker, M.T.; et al. Ontogenetic Transition in Fetal Wound Transforming Growth Factor-β Regulation Correlates with Collagen Organization. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 163, 2459–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, A.R.; Chapman, M.A.; Bushong, E.A.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Lieber, R.L. High resolution three-dimensional reconstruction of fibrotic skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeel, A.; Kim, J.S.; Kirk, J.S.; Smith, R.S.; Bohannon, W.T.; Koutakis, P. Role of transforming growth factor-β in skeletal muscle fibrosis: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekari, A.; Luginbuehl, R.; Hofstetter, W.; Egli, R.J. Transforming growth factor beta signaling is essential for the autonomous formation of cartilage-like tissue by expanded chondrocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ween, M.P.; Oehler, M.K.; Ricciardelli, C. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced protein (TGFBI)/(βig-H3): A matrix protein with dual functions in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 10461–10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguette, M.J.N.; Barrow, K.; Firfirey, F.; Dlamini, S.; Saunders, C.J.; Dandara, C.; Gamieldien, J.; Collins, M.; September, A.V. Exploring new genetic variants within COL5A1 intron 4-exon 5 region and TGF-β family with risk of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. J. Orthop. Res. 2020, 38, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posthumus, M.; Collins, M.; Cook, J.; Handley, C.J.; Ribbans, W.J.; Smith, R.K.W.; Schwellnus, M.P.; Raleigh, S.M. Components of the transforming growth factor-β family and the pathogenesis of human achilles tendon pathology—A genetic association study. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 2090–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raleigh, S.M.; Posthumus, M.; O’Cuinneagain, D.; Van Der Merwe, W.; Collins, M. The GDF5 gene and anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 34, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginevičienė, V.; Jakaitienė, A.; Pranckevičienė, E.; Milašius, K.; Utkus, A. Variants in the myostatin gene and physical performance phenotype of elite athletes. Genes 2021, 12, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leońska-Duniec, A.; Borczyk, M.; Korostyński, M.; Massidda, M.; Maculewicz, E.; Cięszczyk, P. Genetic variants in myostatin and its receptors promote elite athlete status. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Park, S.; Kim, Y.; Jung, J.; Lee, J.; Chang, Y.; Lee, S.P.; Park, B.C.; Wolfe, R.R.; Choi, C.S.; et al. Myostatin Inhibition-Induced Increase in Muscle Mass and Strength Was Amplified by Resistance Exercise Training, and Dietary Essential Amino Acids Improved Muscle Quality in Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacka, A.; Dobaczewski, M.; Frangogiannis, N.G. TGF-β signaling in fibrosis. Growth Factors 2011, 29, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A.; Abraham, D.J. TGF-β signaling and the fibrotic response. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.M.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.J.; Lan, H.Y. TGF-β: The master regulator of fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharraz, Y.; Guerra, J.; Pessina, P.; Serrano, A.L.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Understanding the process of fibrosis in duchenne muscular dystrophy. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 965631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceco, E.; McNally, E.M. Modifying muscular dystrophy through transforming growth factor-β. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 4198–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendias, C.L.; Gumucio, J.P.; Davis, M.E.; Bromley, C.W.; Davis, C.S.; Brooks, S.V. Transforming growth factor-beta induces skeletal muscle atrophy and fibrosis through the induction of atrogin-1 and scleraxis. Muscle Nerve 2012, 45, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, J.R.; Selvaraj, S.; Yue, F.; Kim, A.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Hu, M.; Liu, J.S.; Ren, B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 2012, 485, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Yu, S.J.; Park, B.L.; Cheong, H.S.; Pasaje, C.F.A.; Bae, J.S.; Lee, H.S.; Shin, H.D.; Kim, Y.J. TGFBR3 polymorphisms and its haplotypes associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection and age of hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence. Dig. Dis. 2011, 29, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Jeong, H.W.; Nam, J.O.; Lee, B.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, R.W.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, I.S. Identification of motifs in the fasciclin domains of the transforming growth factor-β-induced matrix protein βig-h3 that interact with the αvβ5 integrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46159–46165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Number of Participants | Number of Men | Number of Women | Average Age | Average Height | Average Body Weight | BMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main groups | |||||||

| Control group | 133 | 86 | 47 | 36.90 | 173.53 | 71.65 | 23.37 |

| Study group | 202 | 159 | 43 | 36.54 | 175.36 | 74.00 | 25.07 |

| Division according to the number of injuries | |||||||

| Single | 26 | 19 | 7 | 36.61 | 173.61 | 72.51 | 32.74 |

| Multiple | 116 | 97 | 19 | 35.94 | 176.10 | 74.59 | 23.90 |

| Division by type of injury | |||||||

| Muscle injury | 142 | 116 | 26 | 36.07 | 175.64 | 74.21 | 25.52 |

| ACL injury | 60 | 43 | 17 | 37.66 | 174.70 | 73.50 | 24.00 |

| Other injury | 57 | 48 | 9 | 35.71 | 175.54 | 74.75 | 24.08 |

| SNP | rs1805117 | SNP | rs1805117 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | No Injuries vs. One Injury | Comparison | No Injuries vs. More Than One Injury | ||||||

| Model | p-Value (p-Value Adjusted) | Genotype | OR | 95% CI | Model | p-Value (p-Value Adjusted) | Genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.41 (1) | TT | 1 | codominant | 0.68 (1) | TT | 1.0 | ||

| TC | 1.50 | 0.81–2.78 | TC | 1.24 | 0.7–2.22 | ||||

| CC | 0.76 | 0.07–8.67 | CC | 1.67 | 0.26–10.5 | ||||

| dominant | 0.22 (0.89) | TT | 1 | dominant | 0.41 (1) | TT | 1.0 | ||

| TC-CC | 1.46 | 0.80–2.67 | TC-CC | 1.27 | 0.72–2.23 | ||||

| recessive | 0.74 (1) | TT-TC | 1 | recessive | 0.63 (1) | TT-TC | 1.0 | ||

| CC | 0.67 | 0.06–7.56 | CC | 1.57 | 0.25–9.8 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.19 (0.74) | TT-GG | 1.0 | overdominant | 0.41 (1) | TT-CC | 1.0 | ||

| TC | 1.51 | 0.82–2.79 | TC | 1.22 | 0.69–2.18 | ||||

| additive | 0.29 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.35 | 0.77–2.37 | additive | 0.38 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.26 | 0.76–2.09 |

| SNP | rs1805117 | SNP | rs1805113 | ||||||

| comparison | one injury vs. more injuries | comparison | no injuries vs. one injury | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.61 (1) | TT | 1.0 | codominant | 0.66 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| TC | 0.8 | 0.44–1.48 | AG | 0.94 | 0.49–1.8 | ||||

| CC | 2.03 | 0.2–20.22 | GG | 1.31 | 0.61–2.83 | ||||

| dominant | 0.58 (1) | TT | 1.0 | dominant | 0.86 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| TC-CC | 0.85 | 0.46–1.54 | AG-GG | 1.05 | 0.58–1.91 | ||||

| recessive | 0.48 (1) | TT-TC | 1.0 | recessive | 0.38 (1) | AA-AG | 1 | ||

| CC | 2.18 | 0.22–21.51 | GG | 1.36 | 0.69–2.68 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.44 (1) | TT-CC | 1.0 | overdominant | 0.57 (1) | AA-GG | 1 | ||

| TC | 0.79 | 0.43–1.45 | AG | 0.85 | 0.48–1.5 | ||||

| additive | 0.76 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.92 | 0.53–1.58 | additive | 0.54 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.13 | 0.77–1.65 |

| SNP | rs1805113 | SNP | rs1805113 | ||||||

| comparison | no injuries vs. more than one injury | comparison | one injury vs. more injuries | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.58 (1) | AA | 1 | codominant | 0.19 (0.77) | AA | 1 | ||

| AG | 1.23 | 0.69–2.19 | AG | 1.3 | 0.68–2.51 | ||||

| GG | 0.86 | 0.4–1.85 | GG | 0.64 | 0.29–1.45 | ||||

| dominant | 0.68 (1) | AA | 1 | dominant | 0.86 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| AG-GG | 1.12 | 0.65–1.93 | AG-GG | 1.06 | 0.57–1.94 | ||||

| recessive | 0.44 (1) | AA-AG | 1 | recessive | 0.10 (0.41) | AA-AG | 1 | ||

| GG | 0.76 | 0.39–1.51 | GG | 0.55 | 0.27–1.13 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.33 (1) | AA-GG | 1 | overdominant | 0.14 (0.57) | AA-GG | 1 | ||

| AG | 1.29 | 0.77–2.16 | AG | 1.54 | 0.86–2.74 | ||||

| additive | 0.88 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.97 | 0.67–1.41 | additive | 0.42 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.27 |

| SNP | rs11333758 | SNP | rs11333758 | ||||||

| comparison | no injuries vs. one injury | comparison | no injuries vs. more than one injury | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.031 (0.12) | AA | 1 | codominant | 0.56 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| A– | 1.91 | 1.06–3.45 | A– | 1.09 | 0.62–1.92 | ||||

| – – | 0.31 | 0.04–2.68 | – – | 1.75 | 0.58–5.25 | ||||

| dominant | 0.074 (0.3) | AA | 1 | dominant | 0.55 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| A– – | 1.69 | 0.95–2.99 | A––– – | 1.18 | 0.69–2.01 | ||||

| recessive | 0.13 (0.53) | AA–A– | 1 | recessive | 0.33 (1) | AA–A– | 1 | ||

| – – | 0.24 | 0.03–2.06 | – – | 1.7 | 0.58–5.03 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.019 (0.077) | AA– – | 1 | overdominant | 0.91 (1) | AA– – | 1 | ||

| A– | 2.01 | 1.12–3.6 | A– | 1.03 | 0.59–1.81 | ||||

| additive | 0.270 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.32 | 0.8–2.18 | additive | 0.39 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.2 | 0.79–1.84 |

| SNP | rs11333758 | SNP | rs1442 | ||||||

| comparison | one injury vs. more than one injury | comparison | no injuries vs. one injury | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.017 (0.067) | AA | 1 | codominant | 0.26 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| A– | 0.58 | 0.32–1.06 | CG | 1.13 | 0.57–2.26 | ||||

| – – | 5.49 | 0.67–44.98 | GG | 1.85 | 0.83–4.11 | ||||

| dominant | 0.25 (1) | AA | 1 | dominant | 0.38 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| A– – | 0.71 | 0.4–1.27 | CG-GG | 1.33 | 0.69–2.56 | ||||

| recessive | 0.024 (0.098) | AA–A– | 1 | recessive | 0.11 (0.44) | CC-CG | 1 | ||

| – – | 6.8 | 0.84–54.91 | GG | 1.7 | 0.89–3.27 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.034 (0.14) | AA– – | 1 | overdominant | 0.54 (1) | CC-GG | 1 | ||

| A– | 0.53 | 0.29–0.96 | CG | 0.84 | 0.48–1.47 | ||||

| additive | 0.84 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.95 | 0.59–1.54 | additive | 0.13 (0.52) | 0,1,2 | 1.36 | 0.91–2.03 |

| SNP | rs1442 | SNP | rs1442 | ||||||

| comparison | no injuries vs. more than one injury | comparison | one injury vs. more than one injury | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.58 (1) | CC | 1 | codominant | 0.60 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| CG | 0.84 | 0.46–1.53 | CG | 0.77 | 0.38–1.56 | ||||

| GG | 1.18 | 0.57–2.42 | GG | 0.67 | 0.31–1.47 | ||||

| dominant | 0.81 (1) | CC | 1 | dominant | 0.35 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| CG–GG | 0.93 | 0.53–1.65 | CG-GG | 0.73 | 0.38–1.41 | ||||

| recessive | 0.39 (1) | CC-CG | 1 | recessive | 0.48 (1) | CC-CG | 1 | ||

| GG | 1.31 | 0.71–2.43 | GG | 0.79 | 0.42–1.5 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.35 (1) | CC–GG | 1 | overdominant | 0.84 (1) | CC-GG | 1 | ||

| CG | 0.78 | 0.47–1.31 | CG | 0.94 | 0.53–1.68 | ||||

| additive | 0.72 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.07 | 0.75–1.53 | additive | 0.32 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.82 | 0.56–1.21 |

| SNP | rs1805117 | SNP | rs1805117 | ||||||

| Comparison | Controls vs. Muscle Strain or Tear | Comparison | Control vs. Other Injuries (Sprains, Breaks, and Twists) | ||||||

| Model | p-Value (p-Value Adjusted) | Genotype | OR | 95% CI | Model | p-Value (p-Value Adjusted) | Genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.68 (1) | TT | 1 | codominant | 0.37 (1) | TT | 1 | ||

| TC | 1.18 | 0.68–2.07 | TC | 1.54 | 0.76–3.08 | ||||

| CC | 1.82 | 0.32–10.63 | CC | 2.5 | 0.33–18.98 | ||||

| dominant | 0.47 (1) | TT | 1 | dominant | 0.18 (0.72) | TT | 1 | ||

| TC–CC | 1.22 | 0.71–2.1 | TC–CC | 1.59 | 0.81–3.14 | ||||

| recessive | 0.53 (1) | TT–TC | 1 | recessive | 0.45 (1) | TT–TC | 1 | ||

| CC | 1.74 | 0.31–9.81 | CC | 2.19 | 0.29–16.47 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.59 (1) | TT–CC | 1 | overdominant | 0.26 (1) | TT–CC | 1 | ||

| TC | 1.16 | 0.67–2.03 | TC | 1.49 | 0.74–2.97 | ||||

| additive | 0.40 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.23 | 0.76–1.99 | additive | 0.16 (0.63) | 0,1,2 | 1.55 | 0.85–2.83 |

| SNP | rs1805117 | SNP | rs1805113 | ||||||

| comparison | controls vs. ACL injury | comparison | controls vs. muscle strain or tear | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.047 (0.19) | TT | 1 | codominant | 0.81 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| TC | 2.05 | 1.05–3.99 | AG | 1.07 | 0.62–1.86 | ||||

| CC | 0 | NA | GG | 0.85 | 0.42–1.75 | ||||

| dominant | 0.053 (0.21) | TT | 1 | dominant | 0.98 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| TC–CC | 1.92 | 0.99–3.72 | AG–GG | 1.01 | 0.6–1.69 | ||||

| recessive | 0.19 (0.77) | TT–TC | 1 | recessive | 0.54 (1) | AA–AG | 1 | ||

| CC | 0 | NA | GG | 0.82 | 0.43–1.56 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.029 (0.12) | TT–CC | 1 | overdominant | 0.62 (1) | AA–GG | 1 | ||

| TC | 2.1 | 1.08–4.08 | AG | 1.13 | 0.69–1.85 | ||||

| additive | 0.11 (0.43) | 0,1,2 | 1.67 | 0.89–3.11 | additive | 0.76 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.95 | 0.67–1.34 |

| SNP | rs1805113 | SNP | rs1805113 | ||||||

| comparison | control vs. other injuries (sprains, breaks, and twists) | comparison | controls vs. ACL injury | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.15 (0.6) | AA | 1 | codominant | 0.51 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| AG | 1.54 | 0.76–3.15 | AG | 1.49 | 0.71–3.11 | ||||

| GG | 0.64 | 0.22–1.85 | GG | 1.53 | 0.62–3.75 | ||||

| dominant | 0.49 (1) | AA | 1 | dominant | 0.25 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| AG–GG | 1.27 | 0.64–2.52 | AG–GG | 1.5 | 0.75–3.01 | ||||

| recessive | 0.12 (0.48) | AA–AG | 1 | recessive | 0.69 (1) | AA–AG | 1 | ||

| GG | 0.49 | 0.19–1.28 | GG | 1.2 | 0.56–2.58 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.078 (0.31) | AA–GG | 1 | overdominant | 0.49 (1) | AA–GG | 1 | ||

| AG | 1.78 | 0.93–3.38 | AG | 1.25 | 0.67–2.35 | ||||

| additive | 0.74 (1) | 0,1,2 | 0.93 | 0.58–1.47 | additive | 0.32 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.25 | 0.81–1.94 |

| SNP | rs11333758 | SNP | rs11333758 | ||||||

| comparison | controls vs. muscle strain or tear | comparison | control vs. other injuries (sprains, breaks and twists) | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.84 (1) | AA | 1 | codominant | 0.24 (0.96) | AA | 1 | ||

| A– | 1.21 | 0.71–2.08 | A– | 1.09 | 0.53–2.21 | ||||

| – – | 1.67 | 0.57–4.86 | – – | 2.76 | 0.85–8.99 | ||||

| dominant | 0.35 (1) | AA | 1 | dominant | 0.40 (1) | AA | 1 | ||

| A– – | 1.28 | 0.77–2.13 | A– – | 1.32 | 0.69–2.53 | ||||

| recessive | 0.40 (1) | AA–A– | 1 | recessive | 0.094 (0.38) | A–A– | 1 | ||

| – – | 1.56 | 0.54–4.49 | – – | 2.69 | 0.85–8.54 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.58 (1) | AA– – | 1 | overdominant | 0.92 (1) | AA– – | 1 | ||

| A– | 1.16 | 0.68–1.97 | A– | 0.96 | 0.48–1.93 | ||||

| additive | 0.28 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.25 | 0.83–1.89 | additive | 0.18 (0.71) | 0,1,2 | 1.41 | 0.86–2.31 |

| SNP | rs11333758 | SNP | rs1442 | ||||||

| comparison | controls vs. ACL injury | comparison | controls vs. muscle strain or tear | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI |

| codominant | 0.017 (0.067) | AA | 1 | codominant | 0.36 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| A– | 1.88 | 0.98–3.62 | CG | 0.87 | 0.48–1.56 | ||||

| – – | 0 | NA | GG | 1.37 | 0.69–2.72 | ||||

| dominant | 0.14 (0.57) | AA | 1 | dominant | 0.96 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| A– – | 1.62 | 0.85–3.07 | CG–GG | 1.01 | 0.59–1.75 | ||||

| recessive | 0.032 (0.18) | AA–A– | 1 | recessive | 0.18 (0.72) | CC–CG | 1 | ||

| – – | 0 | NA | GG | 1.49 | 0.83–2.67 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.035 (0.14) | AA– – | 1 | overdominant | 0.27 (1) | CC–GG | 1 | ||

| A– | 2.02 | 1.05–3.87 | CG | 0.76 | 0.46–1.24 | ||||

| additive | 0.46 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.24 | 0.71–2.16 | additive | 0.41 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.15 | 0.82–1.62 |

| SNP | rs1442 | SNP | rs1442 | ||||||

| comparison | control vs. other injuries (sprains, breaks, and twists) | comparison | controls vs. ACL injury | ||||||

| model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95% CI | model | p-value (p-value adjusted) | genotype | OR | 95%CI |

| codominant | 0.067 (0.27) | CC | 1 | codominant | 0.31 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| CG | 0.58 | 0.27–1.24 | CG | 0.94 | 0.44–2.02 | ||||

| GG | 1.45 | 0.63–3.31 | GG | 1.7 | 0.71–4.07 | ||||

| dominant | 0.58 (1) | CC | 1 | dominant | 0.71 (1) | CC | 1 | ||

| CG–GG | 0.83 | 0.42–1.64 | CG–GG | 1.14 | 0.56–2.34 | ||||

| recessive | 0.063 (0.25) | CC–CG | 1 | recessive | 0.13 (0.50) | CC–CG | 1 | ||

| GG | 1.98 | 0.97–4.04 | GG | 1.77 | 0.86–3.65 | ||||

| overdominant | 0.031 (0.12) | CC–GG | 1 | overdominant | 0.33 (1) | CC–GG | 1 | ||

| CG | 0.49 | 0.25–0.95 | CG | 0.73 | 0.39–1.38 | ||||

| additive | 0.45 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.18 | 0.77–1.82 | additive | 0.25 (1) | 0,1,2 | 1.3 | 0.83–2.04 |

| rs1805113 × rs1805117 interaction results (p = 0.0096239) Association of rs1805113 with rs1805117 (p = 0.0096) | ||||||

| rs1805117 | rs1805113 | ctrl count | injured count | OR | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

| TT | AA | 44 | 55 | 1.00 | - | - |

| CT | AA | 33 | 55 | 1.31 | 0.73 | 2.37 |

| CC | AA | 14 | 19 | 1.10 | 0.49 | 2.45 |

| TT | AG | 0 | 9 | - | - | - |

| CT | AG | 24 | 38 | 1.26 | 0.65 | 2.42 |

| CC | AG | 8 | 15 | 1.39 | 0.54 | 3.62 |

| TT | GG | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| CT | GG | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| CC | GG | 2 | 4 | 1.48 | 0.25 | 8.57 |

| Association of rs1805117 with injury after adjusting for rs1805113 genotype (p = 0.13397) | ||||||

| rs1805117 | rs1805113 | ctrl count | injured count | OR | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

| TT | AA | 44 | 55 | 1.00 | ||

| TT | AG | 0 | 9 | - | - | - |

| TT | GG | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| CT | AA | 33 | 55 | 1.00 | - | - |

| C/T | AG | 24 | 38 | 0.96 | 0.49 | 1.88 |

| CT | GG | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| CC | AA | 14 | 19 | 1.00 | - | - |

| CC | AG | 8 | 15 | 1.27 | 0.42 | 3.87 |

| CC | GG | 2 | 4 | 1.35 | 0.21 | 8.57 |

| Association of rs1805113 with injury after adjusting for rs1805117 genotype (p = 0.0093438) | ||||||

| rs1805117 | rs1805113 | ctrl count | injured count | OR | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

| TT | AA | 44 | 55 | 1.00 | - | - |

| TT | AG | 33 | 55 | 1.31 | 0.73 | 2.37 |

| TT | GG | 14 | 19 | 1.10 | 0.49 | 2.45 |

| CT | AA | 0 | 9 | 1.00 | - | - |

| CT | AG | 24 | 38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - |

| CT | GG | 8 | 15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - |

| CC | AA | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | - | - |

| CC | AG | 0 | 0 | - | - | - |

| CC | GG | 2 | 4 | - | - | - |

| Association of rs1805113 with rs11333758 (p = 0.012725) | ||||||

| rs11333758 | rs1805113 | ctrl count | injured count | OR | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

| AA | AA | 26 | 41 | 1.00 | - | - |

| AA | AG | 35 | 53 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 1.66 |

| AA | GG | 21 | 19 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 1.12 |

| A– | AA | 14 | 21 | 0.79 | 0.33 | 1.85 |

| A– | AG | 20 | 34 | 1.01 | 0.47 | 2.13 |

| A– | GG | 3 | 17 | 3.46 | 0.91 | 13.16 |

| – – | AA | 4 | 2 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 1.56 |

| – – | AG | 2 | 6 | 1.92 | 0.35 | 10.47 |

| – – | GG | 0 | 2 | - | 0.00 | - |

| Association of rs1805113 with injury after adjusting for rs11333758 genotype (p = 0.0020998) | ||||||

| rs11333758 | rs1805113 | ctrl count | injured count | OR | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

| AA | AA | 26 | 41 | 1.00 | - | - |

| AA | AG | 35 | 53 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 1.66 |

| AA | GG | 21 | 19 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 1.12 |

| A– | AA | 14 | 21 | 1.00 | - | - |

| A– | AG | 20 | 34 | 1.28 | 0.53 | 3.11 |

| A– | GG | 3 | 17 | 4.41 | 1.07 | 18.25 |

| – – | AA | 4 | 2 | 1.00 | - | - |

| – – | AG | 2 | 6 | 7.34 | 0.69 | 77.92 |

| – – | GG | 0 | 2 | - | 0.00 | - |

| Association of rs11333758 with injury after adjusting for rs1805113 genotype (p = 0.0039409) | ||||||

| rs11333758 | rs1805113 | ctrl count | injured count | OR | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

| AA | AA | 26 | 41 | 1.00 | - | - |

| A– | AA | 14 | 21 | 0.79 | 0.33 | 1.85 |

| – – | AA | 4 | 2 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 1.56 |

| AA | AG | 35 | 53 | 1.00 | - | - |

| A– | AG | 20 | 34 | 1.18 | 0.58 | 2.39 |

| – – | AG | 2 | 6 | 2.25 | 0.42 | 12.08 |

| AA | GG | 21 | 19 | 1.00 | - | - |

| A– | GG | 3 | 17 | 6.94 | 1.73 | 27.95 |

| – – | GG | 0 | 2 | - | 0.00 | - |

| Haplotype | Association with Being in the Injured Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1805117 | rs1805113 | Frequency | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-Value |

| T | A | 0.552 | 1 | reference haplotype | ||

| T | G | 0.283 | 1.13 | 0.79 | 1.61 | 0.495 |

| C | A | 0.0204 | 1.15 | 0.71 | 1.87 | 0.564 |

| C | G | 0.145 | Inf | Inf | Inf | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rzeszutko-Bełzowska, A.; Leońska-Duniec, A. The Transforming Growth Factor β Genes and Susceptibility to Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Physically Active Caucasian Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010358

Rzeszutko-Bełzowska A, Leońska-Duniec A. The Transforming Growth Factor β Genes and Susceptibility to Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Physically Active Caucasian Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010358

Chicago/Turabian StyleRzeszutko-Bełzowska, Agata, and Agata Leońska-Duniec. 2026. "The Transforming Growth Factor β Genes and Susceptibility to Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Physically Active Caucasian Cohort" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010358

APA StyleRzeszutko-Bełzowska, A., & Leońska-Duniec, A. (2026). The Transforming Growth Factor β Genes and Susceptibility to Musculoskeletal Injuries in a Physically Active Caucasian Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010358