The Obesity Paradox Reconsidered: Evidence from a Multicenter Romanian Hemodialysis Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

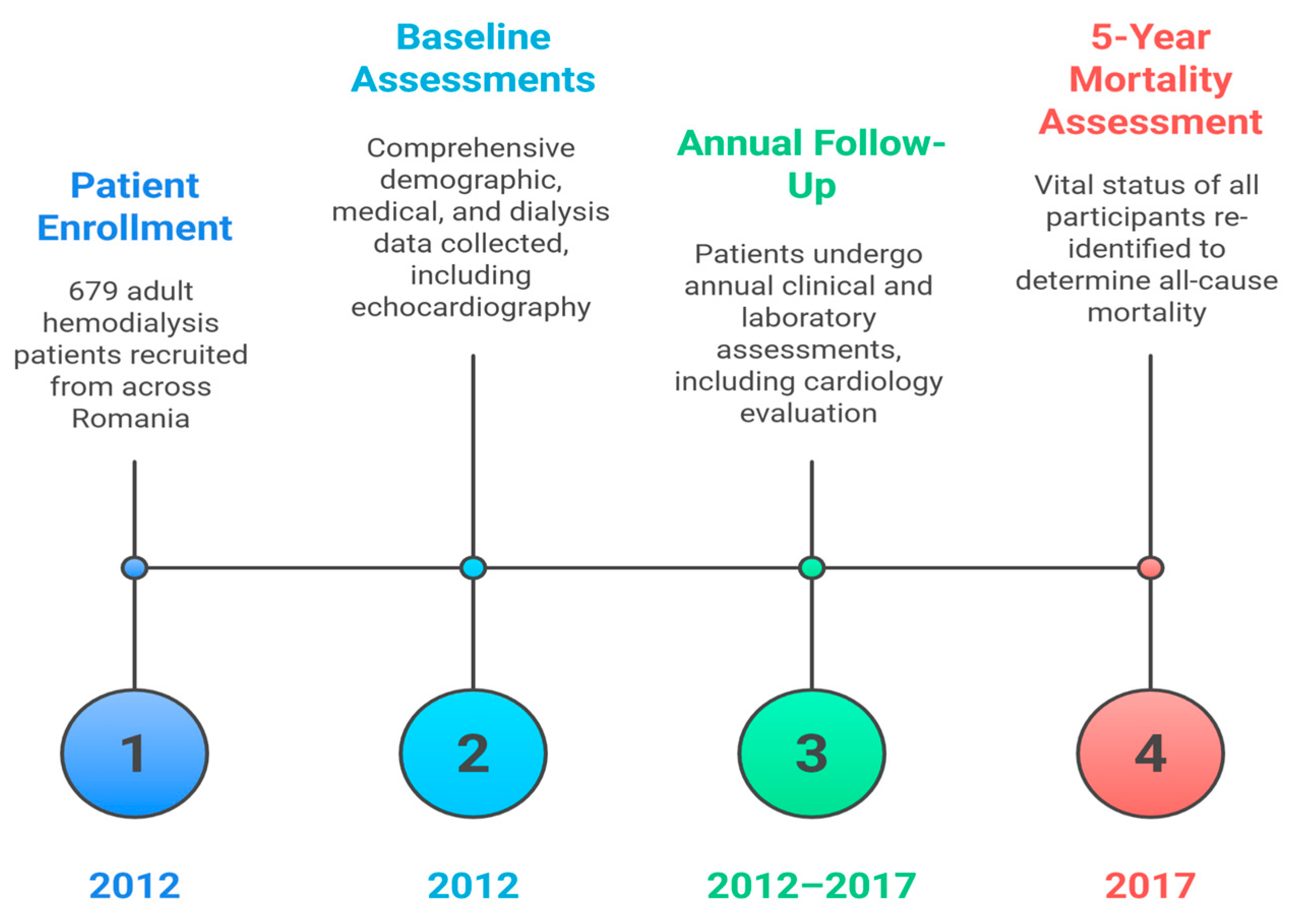

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

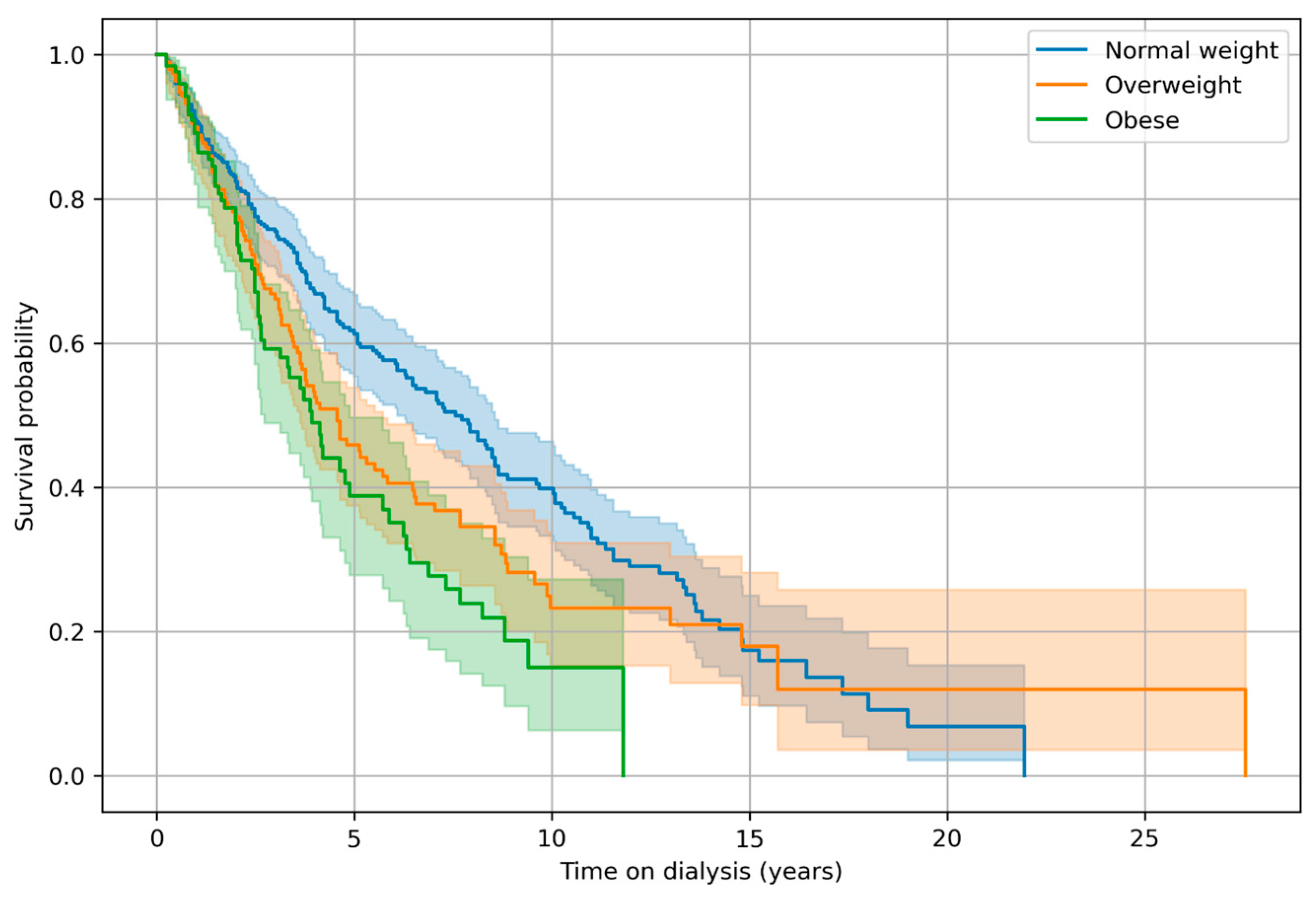

Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koskinas, K.C.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Antoniades, C.; Blüher, M.; Gorter, T.M.; Hanssen, H.; Marx, N.; McDonagh, T.A.; Mingrone, G.; Rosengren, A.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: An ESC Clinical Consensus Statement. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4063–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, C.; Borrelli, S.; Minutolo, R.; Chiodini, P.; De Nicola, L.; Conte, G. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Suggests Obesity Predicts Onset of Chronic Kidney Disease in the General Population. Kidney Int. 2017, 91, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.R.; Grams, M.E.; Ballew, S.H.; Bilo, H.; Correa, A.; Evans, M.; Gutierrez, O.M.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Iseki, K.; Kenealy, T.; et al. Adiposity and Risk of Decline in Glomerular Filtration Rate: Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data in a Global Consortium. BMJ 2019, 364, k5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, A.N.; Kaplan, L.M.; le Roux, C.W.; Schauer, P.R. Management of Obesity in Adults with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Bills, J.E.; Light, R.P. Diagnosing Obesity by Body Mass Index in Chronic Kidney Disease: An Explanation for the “Obesity Paradox?”. Hypertension 2010, 56, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopple, J.D.; Zhu, X.; Lew, N.L.; Lowrie, E.G. Body Weight-for-Height Relationships Predict Mortality in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Int. 1999, 56, 1136–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavey, S.F.; McCullough, K.; Hecking, E.; Goodkin, D.; Port, F.K.; Young, E.W. Body Mass Index and Mortality in “healthier” as Compared with “Sicker” Haemodialysis Patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001, 16, 2386–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddhu, S.; Pappas, L.M.; Ramkumar, N.; Samore, M. Effects of Body Size and Body Composition on Survival in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, 2366–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Abbott, K.C.; Salahudeen, A.K.; Kilpatrick, R.D.; Horwich, T.B. Survival Advantages of Obesity in Dialysis Patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, K.; Tawada, N.; Takanashi, M.; Akahori, T. The Association between Body Mass Index and All-Cause Mortality in Japanese Patients with Incident Hemodialysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, M.; Streja, E.; Rhee, C.M.; Park, J.; Ravel, V.A.; Soohoo, M.; Moradi, H.; Lau, W.L.; Mehrotra, R.; Kuttykrishnan, S.; et al. Examining the Robustness of the Obesity Paradox in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: A Marginal Structural Model Analysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladhani, M.; Craig, J.C.; Irving, M.; Clayton, P.A.; Wong, G. Obesity and the Risk of Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenvinkel, P.; Gillespie, I.A.; Tunks, J.; Addison, J.; Kronenberg, F.; Drueke, T.B.; Marcelli, D.; Schernthaner, G.; Eckardt, K.-U.; Floege, J.; et al. Inflammation Modifies the Paradoxical Association between Body Mass Index and Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinder-Bos, H.A.; van Diepen, M.; Dekker, F.W.; Hoogeveen, E.K.; Franssen, C.F.M.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Gaillard, C.A.J.M. Lower Body Mass Index and Mortality in Older Adults Starting Dialysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harhay, M.N.; Kim, Y.; Milliron, B.-J.; Robinson, L.F. Obesity Weight Loss Phenotypes in CKD: Findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2023, 8, 1352–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.L.; Chertow, G.M.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Herzog, C.A.; Ishani, A.; Israni, A.K.; Ku, E.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; et al. US Renal Data System 2021 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, A8–A12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; James, M.; Wiebe, N.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Manns, B.; Klarenbach, S.; Tonelli, M. Cause of Death in Patients with Reduced Kidney Function. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidell, J.C. Waist Circumference and Waist/Hip Ratio in Relation to All-Cause Mortality, Cancer and Sleep Apnea. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W. Associations of BMI and Waist Circumference with All-Cause Mortality: A 22-Year Cohort Study. Obesity 2019, 27, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, H.J.; Saranathan, A.; Luke, A.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Guichan, C.; Hou, S.; Cooper, R. Increasing Body Mass Index and Obesity in the Incident ESRD Population. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossola, M.; Giungi, S.; Tazza, L.; Luciani, G. Is There Any Survival Advantage of Obesity in Southern European Haemodialysis Patients? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kopple, J.D.; Kilpatrick, R.D.; McAllister, C.J.; Shinaberger, C.S.; Gjertson, D.W.; Greenland, S. Association of Morbid Obesity and Weight Change Over Time With Cardiovascular Survival in Hemodialysis Population. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 46, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safaei, M.; Sundararajan, E.A.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W.; Shapi’i, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Obesity: Understanding the Causes & Consequences of Obesity and Reviewing Various Machine Learning Approaches Used to Predict Obesity. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postorino, M.; Marino, C.; Tripepi, G.; Zoccali, C. Abdominal Obesity and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in End-Stage Renal Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S.; Han, K.-D.; Choi, H.S.; Bae, E.H.; Ma, S.K.; Kim, S.W. Association of Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference with All-Cause Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Streja, E.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Oreopoulos, A.; Noori, N.; Jing, J.; Nissenson, A.R.; Krishnan, M.; Kopple, J.D.; Mehrotra, R.; et al. The Obesity Paradox and Mortality Associated With Surrogates of Body Size and Muscle Mass in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Mehrotra, R.; Rhee, C.M.; Molnar, M.Z.; Lukowsky, L.R.; Patel, S.S.; Nissenson, A.R.; Kopple, J.D.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Serum Creatinine Level, a Surrogate of Muscle Mass, Predicts Mortality in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 2146–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Su, X.; Yu, Z.; Yan, H.; Ma, D.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Ni, Z.; Gu, L.; Fang, W. Association between Sarcopenic Obesity and Mortality in Patients on Peritoneal Dialysis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1342344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazeley, J.; Bieber, B.; Li, Y.; Morgenstern, H.; de Sequera, P.; Combe, C.; Yamamoto, H.; Gallagher, M.; Port, F.K.; Robinson, B.M. C-Reactive Protein and Prediction of 1-Year Mortality in Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, A.; Avesani, C.M.; Regolisti, G.; Adinolfi, M.; Benigno, G.; Delsante, M.; Fiaccadori, E.; Gandolfini, I. Sarcopenic Obesity and Its Relation with Muscle Quality and Mortality in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chang, L.; Yang, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, H. Association of Changes in Body Composition with All-Cause Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Nutrition 2024, 128, 112566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-E.; Yi, J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.; Song, J.H.; Lee, S.W.; Hwang, S.D. The Role of Lean Body Mass in Predicting Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients across Different Age Groups. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruperto, M.; Barril, G. Clinical Significance of Nutritional Status, Inflammation, and Body Composition in Elderly Hemodialysis Patients—A Case–Control Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.; Lee, H.-F.; Yen, M.; Fetzer, S.J.; Lam, L.T. Obesity Measurement Methods Estimated Mortality Risk in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 57, 1585–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogeveen, E.K.; Halbesma, N.; Rothman, K.J.; Stijnen, T.; van Dijk, S.; Dekker, F.W.; Boeschoten, E.W.; de Mutsert, R. Obesity and Mortality Risk among Younger Dialysis Patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabia, J.; Arcos, E.; Carrero, J.J.; Comas, J.; Vallés, M. Does the Obesity Survival Paradox of Dialysis Patients Differ with Age? Blood Purif. 2015, 39, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashistha, T.; Mehrotra, R.; Park, J.; Streja, E.; Dukkipati, R.; Nissenson, A.R.; Ma, J.Z.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Effect of Age and Dialysis Vintage on Obesity Paradox in Long-Term Hemodialysis Patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 63, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanoff, L.B.; Menzie, C.M.; Denkinger, B.; Sebring, N.G.; McHugh, T.; Remaley, A.T.; Yanovski, J.A. Inflammation and Iron Deficiency in the Hypoferremia of Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 31, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mutsert, R.; Snijder, M.B.; van der Sman-de Beer, F.; Seidell, J.C.; Boeschoten, E.W.; Krediet, R.T.; Dekker, J.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Dekker, F.W. Association between Body Mass Index and Mortality Is Similar in the Hemodialysis Population and the General Population at High Age and Equal Duration of Follow-Up. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delautre, A.; Chantrel, F.; Dimitrov, Y.; Klein, A.; Imhoff, O.; Muller, C.; Schauder, N.; Hannedouche, T.; Krummel, T. Metabolic Syndrome in Haemodialysis Patients: Prevalence, Determinants and Association to Cardiovascular Outcomes. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, V.H.H.; Tain, C.F.; Tong, T.Y.Y.; Mok, H.P.P.; Wong, M.T. Are BMI and Other Anthropometric Measures Appropriate as Indices for Obesity? A Study in an Asian Population. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | BMI < 25 kg/m2 | BMI 25–30 kg/m2 | BMI > 30 kg/m2 | Total | p: <25 vs. 25–30 | p: <25 vs. >30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 55.6 ± 14.4 | 59.5 ± 10.9 | 58.0 ± 10.0 | 57.2 ± 12.9 | 0.000 | 0.036 |

| Male sex, n/N (%) | 207/358 (57.8%) | 128/196 (65.3%) | 66/125 (52.8%) | 401/679 (59.1%) | 0.102 | 0.347 |

| Dialysis vintage (yr) | 5.1 ± 4.5 | 4.1 ± 4.0 | 3.2 ± 2.7 | 4.5 ± 4.1 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.3 ± 1.5 | 11.2 ± 1.3 | 11.4 ± 1.2 | 11.3 ± 1.4 | 0.420 | 0.741 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 608.5 ± 484.6 | 511.7 ± 367.9 | 474.0 ± 297.0 | 555.9 ± 426.7 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 7.1 ± 12.8 | 11.1 ± 24.4 | 8.7 ± 13.5 | 8.5 ± 17.1 | 0.034 | 0.254 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.386 | 0.440 |

| Body weight (kg) | 60.9 ± 8.9 | 79.6 ± 7.2 | 98.3 ± 14.6 | 73.2 ± 17.4 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| eKt/V | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.040 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.5 ± 2.3 | 27.6 ± 1.4 | 34.71 ± 4.06 | 26.1 ± 12.7 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Ultrafiltration (mL/session) | 2096.9 ± 1412.1 | 2359.8 ± 1351.4 | 2439.6 ± 1364.7 | 2236.7 ± 1392.0 | 0.032 | 0.018 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 0.700 | 0.467 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 1.5 | 0.292 | 0.002 |

| Ca × PO4 (mg2/dL2) | 40.5 ± 13.4 | 41.8 ± 14.0 | 45.2 ± 14.8 | 41.7 ± 14.0 | 0.303 | 0.002 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 22.5 ± 4.0 | 22.5 ± 3.3 | 22.5 ± 6.9 | 22.5 ± 4.5 | 0.832 | 0.966 |

| iPTH (pg/mL) | 571.0 ± 604.9 | 629.2 ± 683.8 | 629.8 ± 781.1 | 598.6 ± 663.0 | 0.319 | 0.445 |

| TSAT (%) | 33.7 ± 15.4 | 30.0 ± 14.1 | 28.7 ± 11.2 | 31.7 ± 14.5 | 0.004 | 0.000 |

| Coronary artery disease, n/N (%) | 228/354 (64.4%) | 153/196 (78.1%) | 96/125 (76.8%) | 477/675 (70.7%) | 0.001 | 0.011 |

| Heart valve calcifications, n/N (%) | 202/326 (62.0%) | 113/187 (60.4%) | 73/120 (60.8%) | 388/633 (61.3%) | 0.778 | 0.827 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, n/N (%) | 233/327 (71.3%) | 143/188 (76.1%) | 97/120 (80.8%) | 473/635 (74.5%) | 0.258 | 0.052 |

| LVEF (%) | 57.7 ± 8.6 | 56.5 ± 9.7 | 56.6 ± 8.6 | 57.2 ± 9.0 | 0.160 | 0.242 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n/N (%) | 86/358 (24.0%) | 60/196 (30.6%) | 42/125 (33.6%) | 188/679 (27.7%) | 0.107 | 0.045 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n/N (%) | 73/358 (20.4%) | 41/196 (20.9%) | 21/125 (16.8%) | 135/679 (19.9%) | 0.913 | 0.432 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n/N (%) | 52/332 (15.7%) | 51/177 (28.8%) | 41/109 (37.6%) | 144/618 (23.3%) | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Hepatitis B, n/N (%) | 24/357 (6.7%) | 11/196 (5.6%) | 11/125 (8.8%) | 46/678 (6.8%) | 0.716 | 0.429 |

| Hepatitis C, n/N (%) | 93/358 (26.0%) | 35/196 (17.9%) | 14/125 (11.2%) | 142/679 (20.9%) | 0.035 | 0.000 |

| Mortality, n/N (%) | 185/358 (51.7%) | 108/196 (55.1%) | 67/125 (53.6%) | 360/679 (53.0%) | 0.477 | 0.755 |

| Variables | Univariate HR (95% CI) | Univ p | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | Multiv p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.037 (1.028–1.046) | <0.001 | 1.042 (1.031–1.052) | <0.001 |

| Male vs. female | 1.204 (0.972–1.492) | 0.090 | 0.945 (0.74–1.208) | 0.653 |

| Overweight vs. normal weight | 1.185 (0.944–1.488) | 0.143 | 1.022 (0.781–1.339) | 0.873 |

| Obese vs. normal weight | 1.557 (1.188–2.04) | 0.001 | 1.411 (1.008–1.976) | 0.045 |

| LVEF 41–49% vs. LVEF < 35% | 1.278 (0.982–1.664) | 0.068 | 0.725 (0.489–1.075) | 0.110 |

| LVEF ≥ 50% vs. LVEF < 35% | 0.677 (0.544–0.842) | <0.001 | 0.665 (0.482–0.918) | 0.013 |

| Albumin < 4.0 g/dL | 1.536 (1.247–1.892) | <0.001 | 1.198 (0.931–1.541) | 0.160 |

| Hemoglobin < 10 g/dL | 1.164 (0.889–1.524) | 0.270 | 1.155 (0.854–1.563) | 0.350 |

| Ferritin < 200 or >500 ng/mL | 0.833 (0.672–1.033) | 0.096 | 0.749 (0.589–0.952) | 0.018 |

| CRP > 0.5 mg/dL | 1.9 (1.418–2.546) | <0.001 | 1.781 (1.289–2.461) | <0.001 |

| Phosphate > 5.5 mg/dL | 0.785 (0.619–0.995) | 0.045 | 0.85 (0.651–1.108) | 0.229 |

| iPTH < 150 or >600 pg/mL | 0.843 (0.684–1.039) | 0.110 | 0.879 (0.699–1.107) | 0.274 |

| Coronary artery disease (yes vs. no) | 1.261 (0.989–1.608) | 0.062 | 0.789 (0.582–1.068) | 0.125 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (yes vs. no) | 1.351 (1.084–1.685) | 0.007 | 0.903 (0.677–1.205) | 0.488 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (yes vs. no) | 1.475 (1.163–1.872) | 0.001 | 1.032 (0.766–1.39) | 0.837 |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | 1.879 (1.456–2.424) | <0.001 | 1.775 (1.338–2.355) | <0.001 |

| Ultrafiltration > 500 mL/session | 0.626 (0.449–0.874) | 0.006 | 0.702 (0.481–1.026) | 0.067 |

| eKt/V < 1.2 | 1.511 (1.203–1.899) | <0.001 | 1.343 (1.031–1.749) | 0.029 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Motofelea, A.C.; Pecingina, R.; Olariu, N.; Marc, L.; Chisavu, L.; Bob, F.; Mihaescu, A.; Apostol, A.; Schiller, O.; Motofelea, N.; et al. The Obesity Paradox Reconsidered: Evidence from a Multicenter Romanian Hemodialysis Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010357

Motofelea AC, Pecingina R, Olariu N, Marc L, Chisavu L, Bob F, Mihaescu A, Apostol A, Schiller O, Motofelea N, et al. The Obesity Paradox Reconsidered: Evidence from a Multicenter Romanian Hemodialysis Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010357

Chicago/Turabian StyleMotofelea, Alexandru Catalin, Radu Pecingina, Nicu Olariu, Luciana Marc, Lazar Chisavu, Flaviu Bob, Adelina Mihaescu, Adrian Apostol, Oana Schiller, Nadica Motofelea, and et al. 2026. "The Obesity Paradox Reconsidered: Evidence from a Multicenter Romanian Hemodialysis Cohort" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010357

APA StyleMotofelea, A. C., Pecingina, R., Olariu, N., Marc, L., Chisavu, L., Bob, F., Mihaescu, A., Apostol, A., Schiller, O., Motofelea, N., & Schiller, A. (2026). The Obesity Paradox Reconsidered: Evidence from a Multicenter Romanian Hemodialysis Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010357