Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histological Characteristics of Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Symptom Assessment

2.3. Endoscopic Evaluation

2.4. Histological Evaluation

2.5. Definitions

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Symptoms

3.2. Endoscopic Findings

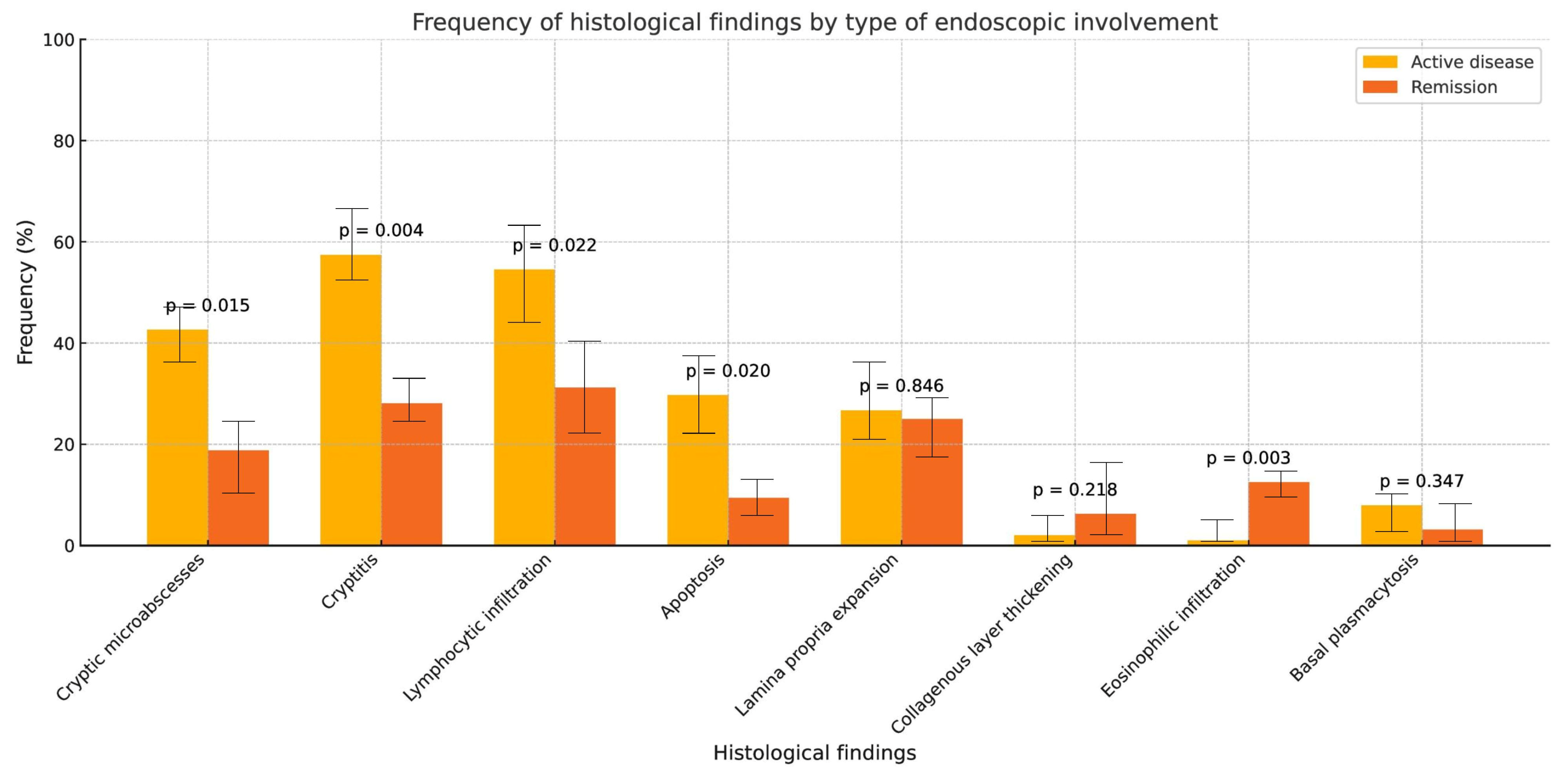

3.3. Histological Findings

3.4. Endoscopic and Histological Findings by Immunotherapy Mechanism

3.5. Symptom–Endoscopy Correlation

3.6. Relationship Between Endoscopic and Histological Findings

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Sorino, C.; Iezzi, S.; Ciuffreda, L.; Falcone, I. Immunotherapy in melanoma: Advances, pitfalls, and future perspectives. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1403021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooradian, M.J.; Sullivan, R.J. Immunotherapy in Melanoma: Recent Advancements and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, K.; Ruiz, R.; Mas, L.; Pozza, D.H.; Vancini, M.; Silva Júnior, J.A.; de Mello, R.A. Update in Immunotherapy for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Optimizing Treatment Sequencing and Identifying the Best Choices. Cancers 2023, 15, 4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Martins, D.; Mendes, F. Immunotherapy in gastric cancer-A systematic review. Oncol. Res. 2025, 33, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, T.; An, Z. Unleashing the Power of immune Checkpoints: A new strategy for enhancing Treg cells depletion to boost antitumor immunity. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 147, 113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Lv, J.; Xiao, Y.; Song, C.; Chen, J.; Shao, C. Small molecule inhibitors targeting PD-L1, CTLA4, VISTA, TIM-3, and LAG3 for cancer immunotherapy (2020–2024). Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 283, 117141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveiro-Barciela, M.; Carballal, S.; Díaz-González, Á.; Mañosa, M.; Gallego-Plazas, J.; Cubiella, J.; Jiménez-Fonseca, P.; Varela, M.; Menchén, L.; Sangro, B.; et al. Management of liver and gastrointestinal toxicity induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Position statement of the AEEH-AEG-SEPD-SEOM-GETECCU. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 47, 401–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogiers, A.; Dimitriou, F.; Lobon, I.; Harvey, C.; Vergara, I.A.; da Silva, I.; Lo, S.N.; Scolyer, R.A.; Carlino, M.S.; Menzies, A.M.; et al. Seasonal patterns of toxicity in melanoma patients treated with combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2024, 198, 113506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakane, T.; Mitsuyama, K.; Yamauchi, R.; Kakuma, T.; Torimura, T. Characteristics of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis: A Systematic Review. Kurume Med. J. 2023, 68, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, P.; Maiorano, B.A.; Ciardiello, D.; Cocomazzi, F.; Carparelli, S.; Guerra, M.; Ingravallo, G.; Cazzato, G.; Carosi, I.; Maiello, E.; et al. Clinic, Endoscopic and Histological Features in Patients Treated with ICI Developing GI Toxicity: Some News and Reappraisal from a Mono-Institutional Experience. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Arai, M.; Akizue, N.; Ohta, Y.; Okimoto, K.; Matsumura, T.; Fan, M.M.; Imai, C.; Tawada, A.; Kato, J.; et al. Colonoscopic evaluation of diarrhea/colitis occurring as an immune-related adverse event. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Mao, E.; Ali, N.; Qiao, W.; Trinh, V.A.; Zobniw, C.; Johnson, D.H.; Samdani, R.; Lum, P.; et al. Endoscopic and Histologic Features of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Hwang, S.W. Endoscopic findings of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related gastrointestinal adverse events. Clin. Endosc. 2024, 57, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, F.; Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Peng, Z.; Xu, T.; Shen, L.; Gong, J.; Wang, X. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis with endoscopic evaluation in Chinese cancer patients: A single-centre retrospective study. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1285478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, N.; Alkhayyat, M.; Lindsey, A.; Mansoor, E.; Saleh, M.A. Immune checkpoint inhibitor induced colitis: A nationwide population-based study. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2022, 46, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.W.; Tremaine, W.J.; Ilstrup, D.M. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutgeerts, P.; Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; Reinisch, W.; Olson, A.; Johanns, J.; Travers, S.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2462–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travis, S.P.; Schnell, D.; Krzeski, P.; Abreu, M.T.; Altman, D.G.; Colombel, J.F.; Feagan, B.G.; Hanauer, S.B.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Marteau, P.R.; et al. Reliability and initial validation of the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Tang, T.; Shatila, M.; Faleck, D.; Harris, J.; Dougan, M.; Olsson-Brown, A.; Johnson, D.B.; Shi, C.; et al. Novel endoscopic scoring system for immune mediated colitis: A multicenter retrospective study of 674 patients. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100, 273–282.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Bermejo, F.; Pajares, R.; Pérez-Calle, J.L.; Rodríguez, M.; Algaba, A.; Mancenido, N.; de la Morena, F.; Carneros, J.A.; McNicholl, A.G.; et al. Oral and intravenous iron treatment in inflammatory bowel disease: Hematological response and quality of life improvement. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthey, L.; Mateus, C.; Mussini, C.; Nachury, M.; Nancey, S.; Grange, F.; Zallot, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Rahier, J.F.; de Beauregard, M.B.; et al. Cancer Immunotherapy with Anti-CTLA-4 Monoclonal Antibodies Induces an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuren, E.C.; van der Eertwegh, A.J.; Wonders, J.; Slangen, R.M.; van Delft, F.; van Bodegraven, A.; Neefjes-Borst, A.; de Boer, N.K. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Characteristics of Ipilimumab-Associated Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Sbeih, H.; Ali, F.S.; Luo, W.; Qiao, W.; Raju, G.S.; Wang, Y. Importance of endoscopic and histological evaluation in the management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geukes Foppen, M.H.; Rozeman, E.A.; van Wilpe, S.; Postma, C.; Snaebjornsson, P.; van Thienen, J.V.; van Leerdam, M.E.; van der Heuvel, M.; Blank, C.U.; van Dieren, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition-related colitis: Symptoms, endoscopic features, histology and response to management. ESMO Open 2018, 3, e000278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, S.; Nakamura, S.; Kawasaki, K.; Toya, Y.; Akasaka, R.; Oizumi, T.; Ishida, K.; Sugai, T.; Matsumoto, T. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced diarrhea: Clinicopathological study of 11 patients. Dig. Endosc. 2020, 32, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Son, H.N.; Hong, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Yang, D.H.; Ye, B.D.; Byeon, J.-S.; Myung, S.-J.; Yang, S.-K.; Yoon, S.; et al. CD8+ cell dominance in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis and its heterogeneity across endoscopic features. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2024, 17, 17562848241309445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasson, S.C.; Slevin, S.M.; Cheung, V.T.; Nassiri, I.; Olsson-Brown, A.; Fryer, E.; Ferreira, R.C.; Trzupek, D.; Gupta, T.; Al-Hillawi, L.; et al. Interferon-Gamma-Producing CD8+ Tissue Resident Memory T Cells Are a Targetable Hallmark of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Colitis. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1229–1244.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, B.C.; Kryczek, I.; Yu, J.; Vatan, L.; Caruso, R.; Matsumoto, M.; Sato, Y.; Shaw, M.H.; Inohara, N.; Xie, Y.; et al. Microbiota-dependent activation of CD4+ T cells induces CTLA-4 blockade-associated colitis via Fcγ receptors. Science 2024, 383, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.F.; Slowikowski, K.; Manakongtreecheep, K.; Sen, P.; Samanta, N.; Tantivit, J.; Nasrallah, M.; Zubiri, L.; Smith, N.P.; Tirard, A.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses reveal distinct immune cell contributions to epithelial barrier dysfunction in checkpoint inhibitor colitis. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overall (N = 196) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Woman | 79 (40.3%) |

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 62.7 (11.4) |

| Range | 20.0–89.0 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |

| Yes | 11 (5.6%) |

| COPD | |

| Yes | 26 (13.3%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Yes | 42 (21.4%) |

| Hypertension | |

| Yes | 83 (42.3%) |

| History of IBD | |

| Yes | 8 (4.1%) |

| Smoking status | |

| Active smoker | 50 (25.5%) |

| Former smoker | 80 (40.8%) |

| Never smoker | 66 (33.7%) |

| Obesity | |

| Yes | 15 (7.7%) |

| Tumor location | |

| Breast | 5 (2.6%) |

| Colon | 8 (4.1%) |

| Genitourinary | 20 (10.2%) |

| Gynecologic | 6 (3.1%) |

| Head and neck | 7 (3.6%) |

| Liver | 11 (5.6%) |

| Lung | 66 (33.7%) |

| Melanoma | 58 (29.6%) |

| Other | 5 (2.6%) |

| Upper GI | 10 (5.1%) |

| Tumor stage | |

| Metastatic | 135 (68.9%) |

| Mechanism of action | |

| CTLA-4 | 42 (21.4%) |

| CTLA-4+PD1 | 4 (2.0%) |

| PD1 | 121 (61.7%) |

| PDL1 | 29 (14.8%) |

| Concomitant therapies | |

| Chemotherapy | 66 (33.7%) |

| Targeted therapy | 44 (22.4%) |

| Immunotherapy cycles | |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2–8) |

| Time from immunotherapy start to symptoms | |

| Median (IQR) | 76.5 (28–197) |

| Prior corticosteroid use | |

| Systemic | 81 (41.3%) |

| Topical | 5 (2.6%) |

| COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Variable | N = 196 |

|---|---|

| Blood in stool | |

| Yes | 76 (39%) |

| Abdominal pain | |

| Absent | 48 (24%) |

| Mild | 69 (35%) |

| Moderate | 75 (38%) |

| Severe | 4 (2%) |

| Bowel movements/24 h, median (IQR) | 8 (6, 10) |

| General condition | |

| Good | 13 (6.6%) |

| Mildly impaired | 50 (26%) |

| Moderately impaired | 117 (60%) |

| Severely impaired | 16 (8.2%) |

| Tachycardia | |

| Yes | 48 (26%) |

| Hemodynamic instability | |

| Yes | 16 (8.2%) |

| Anemia | |

| Yes | 96 (49%) |

| Variable | N = 139 |

|---|---|

| Loss of vascular pattern | |

| Partial | 38 (27%) |

| Total | 73 (53%) |

| No | 28 (20%) |

| Mucosal bleeding | |

| Significant spontaneous | 4 (2.9%) |

| Mild spontaneous | 20 (14%) |

| On contact | 50 (36%) |

| None | 65 (47%) |

| Mucosal lesions | |

| Deep ulcers | 21 (15%) |

| Superficial ulcers | 30 (22%) |

| Aphthae | 45 (32%) |

| None | 43 (31%) |

| Mayo endoscopic score | |

| 3 | 51 (37%) |

| 2 | 45 (32%) |

| 1 | 22 (16%) |

| 0 | 21 (15%) |

| UCEIS classification | |

| Severe | 12 (8.6%) |

| Moderate | 30 (22%) |

| Mild | 61 (44%) |

| Remission | 36 (26%) |

| Variable | N = 141 |

|---|---|

| Crypt abscesses | |

| Yes | 52 (37%) |

| Cryptitis | |

| Yes | 71 (50%) |

| Lymphocytic infiltration | |

| Yes | 68 (48%) |

| Apoptosis | |

| Yes | 36 (26%) |

| Lamina propria expansion | |

| Yes | 37 (26%) |

| Collagen band thickening | |

| Yes | 5 (3.5%) |

| Eosinophilic infiltration | |

| Yes | 5 (3.5%) |

| Basal plasmacytosis | |

| Yes | 9 (6.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Casas Deza, D.; Polo Cuadro, C.; Gascón Ruiz, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Mañosa, M.; Rodríguez-Moranta, F.; Zabana, Y.; Céspedes Martínez, E.; Ordás, I.; Miranda Bautista, J.; et al. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histological Characteristics of Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010353

Casas Deza D, Polo Cuadro C, Gascón Ruiz M, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Mañosa M, Rodríguez-Moranta F, Zabana Y, Céspedes Martínez E, Ordás I, Miranda Bautista J, et al. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histological Characteristics of Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010353

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasas Deza, Diego, Cristina Polo Cuadro, Marta Gascón Ruiz, Manuel Barreiro-de Acosta, Míriam Mañosa, Francisco Rodríguez-Moranta, Yamile Zabana, Elena Céspedes Martínez, Ingrid Ordás, José Miranda Bautista, and et al. 2026. "Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histological Characteristics of Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010353

APA StyleCasas Deza, D., Polo Cuadro, C., Gascón Ruiz, M., Barreiro-de Acosta, M., Mañosa, M., Rodríguez-Moranta, F., Zabana, Y., Céspedes Martínez, E., Ordás, I., Miranda Bautista, J., García, M. J., García de la Filia Molina, I., Roig Ramos, C., Ruiz Cerulla, A., Segarra-Ortega, J. X., Matallana Royo, V., Rodríguez González, E., Martínez de Juan, F., Manceñido Marcos, N., ... García López, S., on behalf of the GETECCU. (2026). Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histological Characteristics of Severe Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Colitis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010353