Causal Mediation Analysis of the Effects of Pain Education on Disability and Pain Intensity in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Interventions

2.3.1. Physiotherapy

2.3.2. Pain Education

2.4. Measurement

2.4.1. Outcome Measures

2.4.2. Mediators

2.5. Analysis

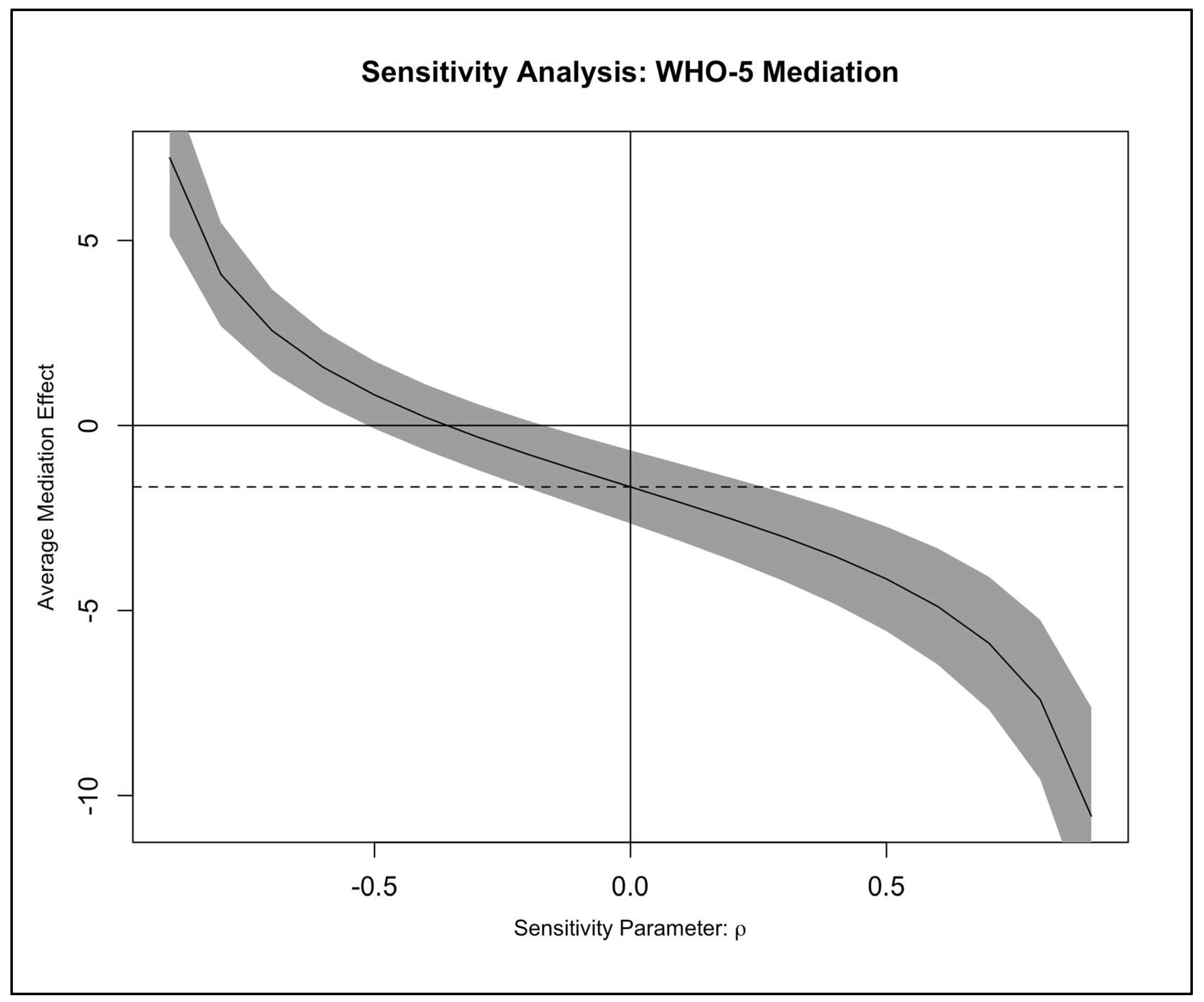

Sensitivity Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Mediation Analysis

3.2.1. Causal Mediation Effects on Disability (RMDQ)

3.2.2. Causal Mediation Effects on Pain Intensity (VAS)

3.3. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Well-Being in the Effect of Pain Education on Disability

4.3. Self-Efficacy as a Non-Significant Mediator

4.4. Implications and Future Directions

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira, M.L.; De Luca, K.; Haile, L.M.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Culbreth, G.T.; Cross, M.; Kopec, J.A.; Ferreira, P.H.; Blyth, F.M.; Buchbinder, R. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; Hoy, D.; Karppinen, J.; Pransky, G.; Sieper, J. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaseem, A.; Wilt, T.J.; McLean, R.M.; Forciea, M.A.; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.A.; Ellis, J.; Ogilvie, R.; Malmivaara, A.; van Tulder, M.W. Exercise therapy for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD009790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatchel, R.J.; Peng, Y.B.; Peters, M.L.; Fuchs, P.N.; Turk, D.C. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.; Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain 2012, 153, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, H. Self-efficacy and chronic pain outcomes: A meta-analytic review. J. Pain 2014, 15, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, E.; Åsenlöf, P.L. Self-efficacy, fear avoidance, and pain intensity as predictors of disability in subacute and chronic musculoskeletal pain patients in primary care health. Pain 2004, 111, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J.; Shaw, W.S. Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.; Linton, S.J. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain 2000, 85, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.M.; Morley, S. The psychological flexibility model: A basis for integration and progress in psychological approaches to chronic pain management. J. Pain 2014, 15, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.B.; Patel, K.V.; Twiddy, H.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Palermo, T.M. Age differences in cognitive–affective processes in adults with chronic pain. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Cancela, J.; Conde Vázquez, O.; Navarro Ledesma, S.; Pruimboom, L. The effectiveness of pain neuroscience education in people with chronic nonspecific low back pain: An umbrella review with meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 68, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryum, T.; Stiles, T.C. Changes in pain catastrophizing, fear-avoidance beliefs, and pain self-efficacy mediate changes in pain intensity on disability in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Pain Rep. 2023, 8, e1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, C.T.; Chernofsky, A.; Lodi, S.; Sherman, K.J.; Saper, R.B.; Roseen, E.J. Do physical therapy and yoga improve pain and disability through psychological mechanisms? A causal mediation analysis of adults with chronic low back pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 52, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, A.; O’Sullivan, K.; O’Sullivan, P.; Purtill, H.; O’Keeffe, M. Examining what factors mediate treatment effect in chronic low back pain: A mediation analysis of a Cognitive Functional Therapy clinical trial. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fordham, B.; Ji, C.; Hansen, Z.; Lall, R.; Lamb, S.E. Explaining how cognitive behavioral approaches work for low back pain: Mediation analysis of the back skills training trial. Spine 2017, 42, E1031–E1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Anderson, M.L.; Balderson, B.H.; Cook, A.J.; Sherman, K.J.; Cherkin, D.C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: Similar effects on mindfulness, catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance in a randomized controlled trial. Pain 2016, 157, 2434–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkin, D.C.; Sherman, K.J.; Balderson, B.H.; Cook, A.J.; Anderson, M.L.; Hawkes, R.J.; Hansen, K.E.; Turner, J.A. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Z.K.; Long, C.R.; Chrischilles, E.; Goertz, C.; Wallace, R.; Casteel, C.; Carnahan, R.M. Secondary causal mediation analysis of a pragmatic clinical trial to evaluate the effect of chiropractic care for US active-duty military on biopsychosocial outcomes occurring through effects on low back pain interference and intensity. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e083509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansell, G.; Hill, J.C.; Main, C.J.; Von Korff, M.; Van Der Windt, D. Mediators of treatment effect in the back in action trial: Using latent growth modeling to take change over time into account. Clin. J. Pain 2017, 33, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidiq, M.; Muzaffar, T.; Janakiraman, B.; Masoodi, S.; Vasanthi, R.K.; Ramachandran, A.; Bansal, N.; Chahal, A.; Kashoo, F.Z.; Rizvi, M.R. Effects of pain education on disability, pain, quality of life, and self-efficacy in chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0294302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashin, A.G.; McAuley, J.H.; Lamb, S.E.; Hopewell, S.; Kamper, S.J.; Williams, C.M.; Henschke, N.; Lee, H. Development of a guideline for reporting mediation analyses (AGReMA). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Guideline Centre (UK). Low Back Pain and Sciatica in Over 16s: Assessment and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Jensen, M.P.; Moseley, G.L.; Abbott, J.H. Pain education for patients with non-specific low back pain in Nepal: Protocol of a feasibility randomised clinical trial (PEN-LBP Trial). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.; Moseley, G. Explain Pain Supercharged; NOI Group Publishers: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley, G.L.; Butler, D.S. The Explain Pain Handbook: Protectometer; NOI Group Publishers: Adelaide, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, M.; Fairbank, J. The Roland–Morris disability questionnaire and the Oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine 2000, 25, 3115–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual analog scale for pain (vas pain), numeric rating scale for pain (nrs pain), mcgill pain questionnaire (mpq), short-form mcgill pain questionnaire (sf-mpq), chronic pain grade scale (cpgs), short form-36 bodily pain scale (sf-36 bps), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (icoap). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, S240–S252. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; Causal and control belief; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1995; Volume 35, p. 82-003. [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. The general self-efficacy scale: Multicultural validation studies. J. Psychol. 2005, 139, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, M.K. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur. J. Pain 2007, 11, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Hübscher, M.; Moseley, G.L.; Kamper, S.J.; Traeger, A.C.; Mansell, G.; McAuley, J.H. How does pain lead to disability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies in people with back and neck pain. Pain 2015, 156, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.; Keele, L.; Tingley, D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J. Applied Regression Analysis and Generalized Linear Models; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.C.C.; Fisher, E.; Hearn, L.; Eccleston, C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD007407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keeffe, M.; O’Sullivan, P.; Purtill, H.; Bargary, N.; O’Sullivan, K. Cognitive functional therapy compared with a group-based exercise and education intervention for chronic low back pain: A multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiech, K. Deconstructing the sensation of pain: The influence of cognitive processes on pain perception. Science 2016, 354, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hooff, M.L.; Vriezekolk, J.E.; Kroeze, R.J.; O’Dowd, J.K.; van Limbeek, J.; Spruit, M. Targeting self-efficacy more important than dysfunctional behavioral cognitions in patients with longstanding chronic low back pain; a longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Gómez, A.F. Mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 2017, 40, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlhauser, Y.; Vogt, L.; Niederer, D. How and how fast does pain lead to disability? A multilevel mediation analysis on structural, temporal and biopsychosocial pathways in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2020, 49, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, J.E.; Keefe, F.J.; Schneider, S.; Junghaenel, D.U.; Bruckenthal, P.; Schwartz, J.E.; Kaell, A.T.; Caldwell, D.S.; McKee, D.; Gould, E. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain is effective, but for whom? Pain 2016, 157, 2115–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.A.; Holtzman, S.; Mancl, L. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive–behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain 2007, 127, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Level | Control (n = 46) | Pain Education (n = 46) | Control (6 Weeks Post-Intervention) (n = 46) | Pain Education (6 Weeks Post-Intervention) (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.52 (13.32) | 42.02 (8.24) | |||

| Gender | Female | 35 (76.1) | 25 (54.3) | ||

| Male | 11 (23.9) | 21 (45.7) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.96 (4.08) | 27.76 (4.28) | |||

| Duration of LBP (months) | 35.85 (50.37) | 20.93 (34.33) | |||

| Level of activity | Light | 14 (30.4) | 17 (37.0) | ||

| Moderate | 23 (50.0) | 20 (43.5) | |||

| Very active | 9 (19.6) | 9 (19.6) | |||

| Smoker | No | 42 (91.3) | 34 (73.9) | ||

| Yes | 4 (8.7) | 12 (26.1) | |||

| Hours of sleep | 6.33 (1.73) | 6.74 (1.32) | |||

| VAS (0–10) | 5.98 (1.71) | 5.70 (1.66) | 5.57 (1.15) | 2.26 (0.88) | |

| RMDQ (0–24) | 15.02 (4.78) | 12.65 (4.71) | 14.00 (4.74) | 5.80 (2.49) | |

| WHO-5 (0–100) | 54.41 (18.56) | 53.48 (17.53) | 56.39 (16.34) | 70.13 (14.42) | |

| GSE (10–40) | 25.78 (6.40) | 25.83 (5.61) | 30.28 (5.84) | 28.85 (5.54) |

| Mediator | Path a 1 | Path b 2 | Total Effect 3 [95% CI] | Direct Effect (ADE) [95% CI] | Indirect Effect (ACME) [95% CI] | ACME p-Value | % Mediated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE | −1.66 [−3.48, 0.16] | −0.06 [−0.21, 0.09] | −7.02 [−8.37, −5.66] | −7.11 [−8.5, −5.68] | 0.1 [−0.15, 0.38] | 0.410 | −1.4 |

| WHO-5 | 14.49 [10.53, 18.45] | −0.11 [−0.18, −0.05] | −7.02 [−8.37, −5.69] | −5.37 [−7.13, −3.67] | −1.66 [−2.8, −0.72] | 0.001 | 23.6 |

| VAS | −3.23 [−3.6, −2.86] | 0.21 [−0.51, 0.94] | −7.01 [−8.4, −5.68] | −6.32 [−8.67, −4.09] | −0.69 [−2.56, 1.39] | 0.508 | 9.9 |

| Mediator | Path a 1 | Path b 2 | Total Effect 3 [95% CI] | Direct Effect (ADE) [95% CI] | Indirect Effect (ACME) [95% CI] | ACME p-Value | % Mediated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE | −1.35 [−3.11, 0.4] | −0.03 [−0.08, 0.01] | −3.21 [−3.57, −2.86] | −3.26 [−3.61, −2.92] | 0.05 [−0.02, 0.16] | 0.254 | −1.4 |

| WHO-5 | 14.32 [10.47, 18.17] | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.01] | −3.21 [−3.57, −2.85] | −3.02 [−3.47, −2.58] | −0.18 [−0.47, 0.1] | 0.226 | 5.7 |

| RMDQ | −7.01 [−8.27, −5.74] | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.08] | −3.23 [−3.59, −2.88] | −3.1 [−3.59, −2.58] | −0.13 [−0.54, 0.29] | 0.580 | 4.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alalawi, A. Causal Mediation Analysis of the Effects of Pain Education on Disability and Pain Intensity in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010348

Alalawi A. Causal Mediation Analysis of the Effects of Pain Education on Disability and Pain Intensity in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010348

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlalawi, Ahmed. 2026. "Causal Mediation Analysis of the Effects of Pain Education on Disability and Pain Intensity in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010348

APA StyleAlalawi, A. (2026). Causal Mediation Analysis of the Effects of Pain Education on Disability and Pain Intensity in Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010348