Factors Affecting Postoperative Satisfaction After Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Presbyopia-Correcting IOLs

3. Ocular Surface Disease

3.1. Dry Eye Disease

3.2. Cornea Irregular Astigmatism

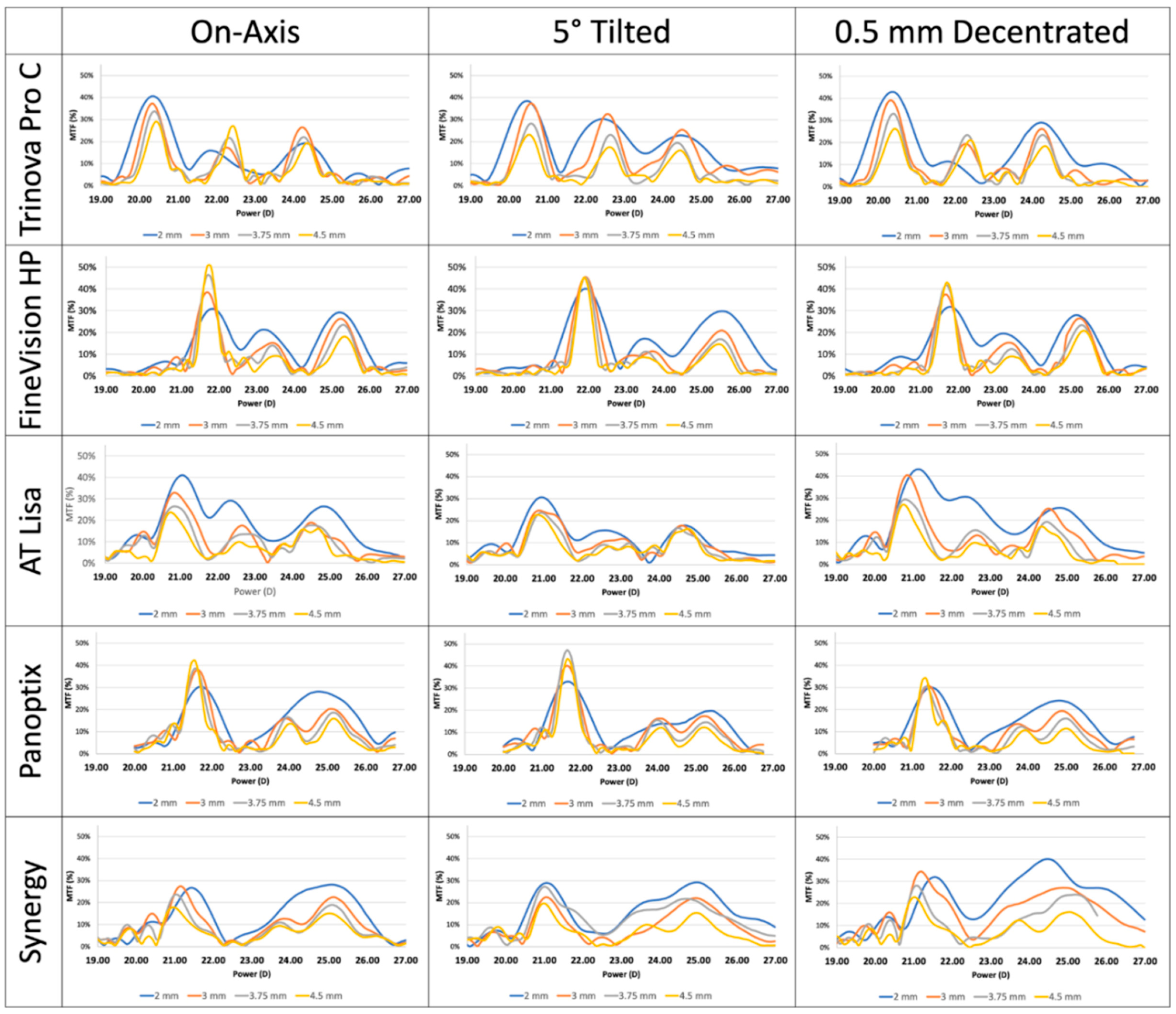

4. Residual Refractive Errors

5. Other Ocular Pathology

5.1. Glaucoma

5.2. Macular Degeneration and Epiretinal Membrane

5.3. Cornea Endothelial Diseases

6. Pupil

7. Tilt and Decentration of Multifocal IOL

8. Large Angle Kappa

9. Choice of Presbyopia Correction Technology

10. Personality and Visual Outcome After Multifocal IOL Implantation

11. Postoperative Management

12. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stern, B.; Gatinel, D.; Nicolaos, G.; Grise-Dulac, A. Intraocular lens models: Ecological distribution footprint and usage trends at a large ophthalmology centre. Eye 2025, 39, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, N.E.; Nuijts, R.M. Multifocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery: Literature review of benefits and side effects. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2013, 39, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanclerz, P.; Toto, F.; Grzybowski, A.; Alio, J.L. Extended Depth-of-Field Intraocular Lenses: An Update. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 9, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampat, R.; Gatinel, D. Multifocal and Extended Depth-of-Focus Intraocular Lenses in 2020. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, e164–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alio, J.L.; Plaza-Puche, A.B.; Fernandez-Buenaga, R.; Pikkel, J.; Maldonado, M. Multifocal intraocular lenses: An overview. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2017, 62, 611–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greve, D.; Bertelmann, E.; Pilger, D.; von Sonnleithner, C. Visual outcome and optical quality of a wavefront-engineered extended depth-of-focus intraocular lens. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2021, 47, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abela-Formanek, C.; Amon, M.; Auffarth, G.U.; Bostanci, B.; Carones, F.; Corbett, D.; Ferreira, T.B.; Mantry, S.; Saad, A.; Llovet, F.; et al. Performance of the First Spiral Refractive Intraocular Lens for Continuous Full Range of Vision. J. Refract. Surg. 2025, 41, e1213–e1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, D.R.H.; Kaymak, H.; Ax, T.; Kretz, F.T.A.; Auffarth, G.U.; Hagen, P.R. Multifocal Intraocular Lenses and Extended Depth of Focus Intraocular Lenses. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 6, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvornicanin, J.; Zvornicanin, E. Premium intraocular lenses: The past, present and future. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2018, 30, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, K.; Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Yao, K. Comparison of trifocal or hybrid multifocal-extended depth of focus intraocular lenses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, N.E.; Webers, C.A.; Touwslager, W.R.; Bauer, N.J.; de Brabander, J.; Berendschot, T.T.; Nuijts, R.M. Dissatisfaction after implantation of multifocal intraocular lenses. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2011, 37, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Tu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Rao, Z.; He, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Tong, Y. A comparative analysis of visual quality and patient satisfaction between monofocal and multifocal intraocular lenses in cataract surgery. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2025, 69, 101826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodov, L.; Reitblat, O.; Levy, A.; Assia, E.I.; Kleinmann, G. Visual Outcomes and Patient Satisfaction for Trifocal, Extended Depth of Focus and Monofocal Intraocular Lenses. J. Refract. Surg. 2019, 35, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, L.C.; Tiveron, M.C., Jr.; Alio, J.L. Multifocal intraocular lenses: Types, outcomes, complications and how to solve them. Taiwan. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 7, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuuminen, R.; Jeon, S.; Jung, B.J.; Moon, K. Prognostic factors for dysphotopsia and spectacle-independent visual function after implantation of non-diffractive extending focus intraocular lenses. Acta Ophthalmol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukai, Y.; Mito, T.; Nakatsugawa, Y.; Seki, Y.; Mita, N.; Shibuya, E.; Yamazaki, M.; Kubo, E.; Sasaki, H. Risk factors for photic phenomena in two different multifocal diffractive intraocular lenses. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, M.A.; Randleman, J.B.; Stulting, R.D. Dissatisfaction after multifocal intraocular lens implantation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2009, 35, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnen, T.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Suryakumar, R. A review of angle kappa and multifocal intraocular lenses and their effect on visual outcomes. Acta Ophthalmol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, A.; Ali, T.K.; Waren, D.P.; Donaldson, K.E. Causes and correction of dissatisfaction after implantation of presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 1965–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mester, U.; Vaterrodt, T.; Goes, F.; Huetz, W.; Neuhann, I.; Schmickler, S.; Szurman, P.; Gekeler, K. Impact of personality characteristics on patient satisfaction after multifocal intraocular lens implantation: Results from the “happy patient study”. J. Refract. Surg. 2014, 30, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, L.; Xue, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, Q. Comparison of the Clinical Performance of Refractive Rotationally Asymmetric Multifocal IOLs with Other Types of IOLs: A Meta-Analysis. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 2018, 4728258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisic, A.; Dekaris, I.; Gabric, N.; Bohac, M.; Romac, I.; Mravicic, I.; Lazic, R. Comparison of diffractive and refractive multifocal intraocular lenses in presbyopia treatment. Coll. Antropol. 2008, 32, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Zhao, J.Y.; Zhang, J.S. Aspheric multifocal intraocular lens. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 423-423.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnen, T.; Herzog, M.; Hemkeppler, E.; Schonbrunn, S.; De Lorenzo, N.; Petermann, K.; Bohm, M. Visual Performance of a Quadrifocal (Trifocal) Intraocular Lens Following Removal of the Crystalline Lens. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 184, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, R.R.; Dey, A.; Bhattacharrya, S.; Bahulayan, A. AcrySof IQ PanOptix Intraocular Lens Versus Extended Depth of Focus Intraocular Lens and Trifocal Intraocular Lens: A Clinical Overview. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 8, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megiddo-Barnir, E.; Alio, J.L. Latest Development in Extended Depth-of-Focus Intraocular Lenses: An Update. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 12, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S.S.; Jun, J.J.; Mak, S.; Booth, M.S.; Shekelle, P.G. Effectiveness of multifocal and monofocal intraocular lenses for cataract surgery and lens replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 257, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatinel, D.; Debellemaniere, G.; Saad, A.; Rampat, R. Theoretical Relationship Among Effective Lens Position, Predicted Refraction, and Corneal and Intraocular Lens Power in a Pseudophakic Eye Model. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, G.; Hoffer, K.J.; Lombardo, M.; Serrao, S.; Schiano-Lomoriello, D.; Ducoli, P. Influence of the effective lens position, as predicted by axial length and keratometry, on the near add power of multifocal intraocular lenses. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Gong, J.; Wu, N.; Yao, Y. Extended depth of focus IOL in eyes with different axial myopia and targeted refraction. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trattler, W.B.; Majmudar, P.A.; Donnenfeld, E.D.; McDonald, M.B.; Stonecipher, K.G.; Goldberg, D.F. The Prospective Health Assessment of Cataract Patients’ Ocular Surface (PHACO) study: The effect of dry eye. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, S.Y.; Jun, I.; Choi, M.; Seo, K.Y.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, T.I. Perioperative Ocular Parameters Associated with Persistent Dry Eye Symptoms After Cataract Surgery. Cornea 2018, 37, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, E.; Marelli, L.; Bonsignore, F.; Lucentini, S.; Luccarelli, S.; Sacchi, M.; Serafino, M.; Nucci, P. The Ocular Surface Frailty Index as a Predictor of Ocular Surface Symptom Onset after Cataract Surgery. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, C.E.; Gupta, P.K.; Farid, M.; Beckman, K.A.; Chan, C.C.; Yeu, E.; Gomes, J.A.P.; Ayers, B.D.; Berdahl, J.P.; Holland, E.J.; et al. An algorithm for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment of ocular surface disorders. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2019, 45, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshigawara, T.; Meguro, A.; Mizuki, N. Impact of Perioperative Dry Eye Treatment with Rebamipide Versus Artificial Tears on Visual Outcomes After Cataract Surgery in Japanese Population. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 1479–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshigawara, T.; Akaishi, M.; Mizuki, Y.; Takeuchi, M.; Yabuki, K.; Hata, S.; Meguro, A.; Mizuki, N. Dry Eye Treatment with Intense Pulsed Light for Improving Visual Outcomes After Cataract Surgery with Diffractive Trifocal Intraocular Lens Implantation. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, S.; Maeda, N. Corneal Topography for Intraocular Lens Selection in Refractive Cataract Surgery. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, e142–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chay, I.W.; Lin, S.T.; Lim, E.W.; Heng, W.J.; Bin Ismail, M.A.; Tan, M.C.; Zhao, P.S.; Nah, G.K.; Ang, B.C. Higher order aberrations and visual function in a young Asian population of high myopes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, T.; Tomidokoro, A.; Samejima, T.; Miyata, K.; Sato, M.; Kaji, Y.; Oshika, T. Corneal regular and irregular astigmatism assessed by Fourier analysis of videokeratography data in normal and pathologic eyes. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almorin-Fernandez-Vigo, I.; Pagan Carrasco, S.; Sanchez-Guillen, I.; Fernandez-Vigo, J.I.; Macarro-Merino, A.; Kudsieh, B.; Fernandez-Vigo, J.A. Influence of Biometric and Corneal Tomographic Parameters on Normative Corneal Aberrations Measured by Root Mean Square. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, X.; Ortega-Usobiaga, J.; Zheng, H.; Luo, W.; Tu, B.; Wang, Y. Characteristics and influencing factors of corneal higher-order aberrations in patients with cataract. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga-Mele, R.; Chang, D.; Dewey, S.; Foster, G.; Henderson, B.A.; Hill, W.; Hoffman, R.; Little, B.; Mamalis, N.; Oetting, T.; et al. Multifocal intraocular lenses: Relative indications and contraindications for implantation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2014, 40, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, N. Assessment of Corneal Optical Quality for Premium IOLs with Pentacam. Highlights Ophthalmol. 2011, 39, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Bradley, A.; Thibos, L.N. Impact of primary spherical aberration, spatial frequency and Stiles Crawford apodization on wavefront determined refractive error: A computational study. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2013, 33, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Qian, D.; Jing, Q.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y. Analysis of Corneal Spherical Aberrations in Cataract Patients with High Myopia. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Buenaga, R.; Alio, J.L.; Perez Ardoy, A.L.; Quesada, A.L.; Pinilla-Cortes, L.; Barraquer, R.I. Resolving refractive error after cataract surgery: IOL exchange, piggyback lens, or LASIK. J. Refract. Surg. 2013, 29, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeely, R.N.; Pazo, E.; Millar, Z.; Richoz, O.; Nesbit, A.; Moore, T.C.; Moore, J.E. Threshold limit of postoperative astigmatism for patient satisfaction after refractive lens exchange and multifocal intraocular lens implantation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2016, 42, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallhorn, S.C.; Hettinger, K.A.; Hannan, S.J.; Venter, J.A.; Teenan, D.; Schallhorn, J.M. Effect of residual sphere on uncorrected visual acuity and satisfaction in patients with monofocal and multifocal intraocular lenses. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2024, 50, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rementeria-Capelo, L.A.; Contreras, I.; Moran, A.; Lorente-Hevia, P.; Marinas, L.; Ruiz-Alcocer, J. Visual Performance of Eyes with Residual Refractive Errors after Implantation of an Extended Vision Intraocular Lens. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 2023, 7701390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.A.; Bala, C.; Alarcon, A.; Vilupuru, S. Tolerance to refractive error with a new extended depth of focus intraocular lens. Eye 2024, 38, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichhpujani, P.; Thakur, S.; Spaeth, G.L. Contrast Sensitivity and Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2020, 29, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.S.Y.; Ang, B.C.H.; Dorairaj, E.; Dorairaj, S. Premium Intraocular Lenses in Glaucoma-A Systematic Review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Sanchez, C.; Rementeria-Capelo, L.A.; Puerto, B.; Lopez-Caballero, C.; Moran, A.; Sanchez-Pina, J.M.; Contreras, I. Visual Function and Patient Satisfaction with Multifocal Intraocular Lenses in Patients with Glaucoma and Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 2021, 9935983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aychoua, N.; Junoy Montolio, F.G.; Jansonius, N.M. Influence of multifocal intraocular lenses on standard automated perimetry test results. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013, 131, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Ahn, J.; Seo, M.; Bae, H.W.; Kim, C.Y.; Choi, W. Efficacy and safety of the enhanced monofocal intraocular lens in glaucoma of varying severity. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcola, A.; Lauzirika, G.; Illarramendi, I.; Soto-Velasco, A.; Sanchez-Avila, R.; Fuente-Garcia, C.; Fernandez-Garcia, A. Evaluation of Visual, Refractive, and Functional Outcomes after Implantation of an Extended Depth of Focus Intraocular Lens in Patients with Stable and Mild Glaucoma. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, T.J.; Wilson, C.W.; Shafer, B.M.; Berdahl, J.P.; Terveen, D.C. Clinical Outcomes of a Non-Diffractive Extended Depth-of-Focus IOL in Eyes with Mild Glaucoma. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 17, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissen-Miyajima, H.; Ota, Y.; Yuki, K.; Minami, K. Implantation of diffractive extended depth-of-focus intraocular lenses in normal tension glaucoma eyes: A case series. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2023, 29, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tojo, N.; Otsuka, M.; Nitta, Y.; Hayashi, A. Effect of enhanced monofocal intraocular lenses on glaucoma patients’ foveal threshold. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Tchah, H. Clinical outcomes after implantation of a new monofocal intraocular lens with enhanced intermediate function in patients with preperimetric glaucoma. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1260298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, J.W.; Lee, J.H.; Zhang, H.; Sung, M.S.; Park, S.W. Comparison of the Visual Outcomes of Enhanced and Standard Monofocal Intraocular Lens Implantations in Eyes with Early Glaucoma. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.B.; Snyder, M.E.; Riemann, C.D.; Foster, R.E.; Sisk, R.A. Short-term outcomes of combined pars plana vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane and phacoemulsification surgery with multifocal intraocular lens implantation. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeon, S. Visual outcomes of epiretinal membrane removal after diffractive-type multifocal intraocular lens implantation. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Choi, A.; Kwon, H. Clinical outcomes after implantation of extended depth-of-focus AcrySof(R) Vivity(R) intraocular lens in eyes with low-grade epiretinal membrane. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 3883–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sararols, L.; Guarro, M.; Vazquez, M.; Ruiz, S.; Lopez, E.; Biarnes, M. Visual Outcomes Following Non-Diffractive Extended-Depth-of-Focus Intraocular Lens Implantation in Patients with Epiretinal Membrane in One Eye and Bilateral Cataracts. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitblat, O.; Velleman, D.A.; Levy, A.; Assia, E.I.; Kleinmann, G. Performance of Extended Depth of Focus Intraocular Lens in Eyes with Preexisting Retinal Disease. Ophthalmologica 2024, 247, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S.; Lee, D.; Park, J.H. Clinical Outcomes of Combined Phacoemulsification, Extended Depth-of-Focus Intraocular Lens Implantation, and Epiretinal Membrane Peeling Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.W.; Ono, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Tsuneya, M.; Abe, Y.; Omoto, T.; Taketani, Y.; Toyono, T.; Aihara, M.; Miyai, T. Regular and irregular astigmatism of bullous keratopathy using Fourier harmonic analysis with anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaup, S.; Pandey, S.K. Cataract surgery in patients with Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy. Community Eye Health 2019, 31, 86–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.Y.; Kuo, Y.S.; Lin, P.Y. Cataract surgery in patients with Fuchs’ dystrophy and corneal decompensation indicated for Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, R.O.; Price, M.O.; Price, F.W., Jr.; Ambrosio, R., Jr.; Belin, M.W. Pentacam characterization of corneas with Fuchs dystrophy treated with Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. J. Refract. Surg. 2010, 26, 972–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnalich-Montiel, F.; Mingo-Botin, D.; Diaz-Montealegre, A. Keratometric, Pachymetric, and Surface Elevation Characterization of Corneas with Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy Treated with DMEK. Cornea 2019, 38, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorcia, V.; Matteoni, S.; Scorcia, G.B.; Scorcia, G.; Busin, M. Pentacam assessment of posterior lamellar grafts to explain hyperopization after Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, V.A.; Son, H.S.; Yildirim, T.M.; Meis, J.; Labuz, G.; Auffarth, G.U.; Khoramnia, R. Refractive outcomes after DMEK: Meta-analysis. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2023, 49, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglio, R.; Vinciguerra, A.L.; Grotto, A.; Milan, S.; Tognetto, D. Hitting the refractive target in corneal endothelial transplantation triple procedures: A systematic review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2024, 69, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, E.D.; Price, F.W., Jr.; Miller, J.; McKee, Y.; Price, M.O. Refractive outcomes of Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty triple procedures (combined with cataract surgery). J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2015, 41, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, M.O.; Pinkus, D.; Price, F.W., Jr. Implantation of Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lenses Staged After Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty in Patients with Fuchs Dystrophy. Cornea 2020, 39, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau-Most, M.; Reitblat, O.; Levy, A.; Assia, E.I.; Kleinmann, G. Clinical outcomes of presbyopia-correcting intraocular lenses in patients with Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.; Rodriguez-Vallejo, M.; Martinez, J.; Burguera, N.; Pinero, D.P. Pupil Diameter in Patients with Multifocal Intraocular Lenses. J. Refract. Surg. 2020, 36, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellopoulos, A.J.; Asimellis, G.; Georgiadou, S. Digital pupillometry and centroid shift changes after cataract surgery. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2015, 41, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandogan, T.; Son, H.S.; Choi, C.Y.; Knorz, M.C.; Auffarth, G.U.; Khoramnia, R. Laboratory Evaluation of the Influence of Decentration and Pupil Size on the Optical Performance of a Monofocal, Bifocal, and Trifocal Intraocular Lens. J. Refract. Surg. 2017, 33, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, E.; Senel, E.C.; Holmstrom, S.T.S.; Pinero, D.P. Comparison of the optical behaviour of five different multifocal diffractive intraocular lenses in a model eye. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, I.D.; Yan, W.; Auffarth, G.U.; Khoramnia, R.; Labuz, G. Optical Quality and Higher Order Aberrations of Refractive Extended Depth of Focus Intraocular Lenses. J. Refract. Surg. 2023, 39, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Thompson, K.; Burns, S.A. Pupil location under mesopic, photopic, and pharmacologically dilated conditions. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 2508–2512. [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi, M.; Shiba, T. Diffractive multifocal intraocular lens implantation in eyes with a small-diameter pupil. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Zhao, T.Y.; Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, W. Tilt and decentration with various intraocular lenses: A narrative review. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 3639–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, M.; Buhren, J.; Kohnen, T. Tilt and decentration of spherical and aspheric intraocular lenses: Effect on higher-order aberrations. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2009, 35, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Hayashi, H.; Nakao, F.; Hayashi, F. Correlation between pupillary size and intraocular lens decentration and visual acuity of a zonal-progressive multifocal lens and a monofocal lens. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 2011–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellucci, R.; Curatolo, M.C. A New Extended Depth of Focus Intraocular Lens Based on Spherical Aberration. J. Refract. Surg. 2017, 33, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Yaish, S.; Zlotnik, A.; Raveh, I.; Yehezkel, O.; Belkin, M.; Zalevsky, Z. Intraocular omni-focal lens with increased tolerance to decentration and astigmatism. J. Refract. Surg. 2010, 26, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, T.; Lu, Y. Effect of Decentration on the Optical Quality of Monofocal, Extended Depth of Focus, and Bifocal Intraocular Lenses. J. Refract. Surg. 2019, 35, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Du, Y.; Wei, L.; Yao, Y.; He, W.; Qian, D.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, X. Distribution of angle alpha and angle kappa in a population with cataract in Shanghai. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2021, 47, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, A.; Ridgway, C.; Gatinel, D.; Debellemaniere, G.; Mimouni, M.; Albert, D.; Cohen, M.; Lloyd, J.; Gauvin, M. Angle Kappa Influence on Multifocal IOL Outcomes. J. Refract. Surg. 2023, 39, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.H.; Waring, G.O.t. The subject-fixated coaxially sighted corneal light reflex: A clinical marker for centration of refractive treatments and devices. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 158, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, G.; Prakash, D.R.; Agarwal, A.; Kumar, D.A.; Agarwal, A.; Jacob, S. Predictive factor and kappa angle analysis for visual satisfactions in patients with multifocal IOL implantation. Eye 2011, 25, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Lin, J.; Leng, L.; Zhao, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; Hu, L. Role of angle kappa in visual quality in patients with a trifocal diffractive intraocular lens. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2018, 44, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holladay, J.T.; Simpson, M.J. Negative dysphotopsia: Causes and rationale for prevention and treatment. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2017, 43, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, R.E.T.; Doroy, Z.A.M.; Yao, J.A.A.; Cruz, E.M. Correlation of angle kappa and angle alpha on visual outcomes in eyes implanted with three types of multifocal intraocular lenses. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hannan, S.J.; Schallhorn, S.C.; Schallhorn, J.M. Angle Kappa is Not Correlated with Patient-Reported Outcomes After Multifocal Lens Implantation. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2024, 18, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusnik, A.; Petrovski, G.; Lumi, X. Dysphotopsias or Unwanted Visual Phenomena after Cataract Surgery. Life 2022, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, S.; Artal, P.; Lundstrom, L.; Yoon, G. Visual simulation of intraocular lenses: Technologies and applications [Invited]. Biomed. Opt. Express 2025, 16, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomro, S.R.; Sager, S.; Paniagua-Diaz, A.M.; Prieto, P.M.; Artal, P. Head-mounted adaptive optics visual simulator. Biomed. Opt. Express 2024, 15, 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Chen, H.; Fan, W. Comparison of bilateral implantation of an extended depth of focus lenses and a blend approach of extended depth of focus lenses and bifocal lenses in cataract patients. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.M.; Miranda, A.C.; Patricio, M.M.; McAlinden, C.; Silva, F.L.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Murta, J.N. Functional magnetic resonance imaging to assess neuroadaptation to multifocal intraocular lenses. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2017, 43, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Xiao, W.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Dong, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Comparison of Visual Neuroadaptations After Multifocal and Monofocal Intraocular Lens Implantation. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 648863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, N.; Gursoy, E. Exploring multifocal IOL experiences: A qualitative study of patient and physician narratives on YouTube. Medicine 2025, 104, e43889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeu, E.; Cuozzo, S. Matching the Patient to the Intraocular Lens: Preoperative Considerations to Optimize Surgical Outcomes. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, e132–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudalevicius, P.; Lekaviciene, R.; Auffarth, G.U.; Liutkeviciene, R.; Jasinskas, V. Relations between patient personality and patients’ dissatisfaction after multifocal intraocular lens implantation: Clinical study based on the five factor inventory personality evaluation. Eye 2020, 34, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.L.; Raimundo, M.; Gil, J.Q.; Henriques, J.; Rosa, A.M.; Quadrado, M.J.; Lobo, C.; Murta, J.N. The influence of personality on the quality of vision after multifocal intraocular lens implantation. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 34, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Du, Z.; Lai, C.; Seth, I.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liao, H.; Hu, Y.; Yu, H.; et al. The association between cataract surgery and mental health in older adults: A review. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 2300–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Fan, Z.; Gao, X.; Huang, W.; Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Lin, M.; Xiao, H.; Ge, J. Illness uncertainty, anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma or cataract. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marilov, V.V.; Shorikhina, O.M. Mental disorders in patients admitted for cataract surgery. Zh Nevrol. Psikhiatr Im. S S Korsakova 2009, 109, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.Y.; Jung, E.H.; Bae, H.W.; Kim, S.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.J. Risk of Depression in Persistent Blue Light Deprivation after Cataract Surgery: APopulation-BasedCohort Study. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrowski, O.; Tavernier, E.; Souied, E.H.; Desmidt, T.; Le Gouge, A.; Bellicaud, D.; Cochener, B.; Limousin, N.; Hommet, C.; Autret-Leca, E.; et al. Sleep and mood changes in advanced age after blue-blocking (yellow) intra ocular lens (IOLs) implantation during cataract surgical treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, P.A.; Al-Dasooqi, D.; Bruce, R.; Prem-Senthil, M. A Review of Ocular Complications Associated with Medications Used for Anxiety, Depression, and Stress. Clin. Optom. 2022, 14, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.A.; Bitsios, P.; Szabadi, E.; Bradshaw, C.M. Comparison of the antidepressants reboxetine, fluvoxamine and amitriptyline upon spontaneous pupillary fluctuations in healthy human volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2000, 149, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.A.; Riedel, W.J.; Vuurman, E.F.; Kruizinga, M.; Ramaekers, J.G. Modulation of the critical flicker fusion effects of serotonin reuptake inhibitors by concomitant pupillary changes. Psychopharmacology 2002, 160, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanten, J.C.; Bauer, N.J.C.; Berendschot, T.; van den Biggelaar, F.; Nuijts, R. Dissatisfaction after implantation of EDOF intraocular lenses. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2025, 51, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, R.K.; Doane, J.; Weinstock, R.; Donaldson, K.E.; Group, A.P.C.S. Work Intensity of Postoperative Care Following Implantation of Presbyopia-Correcting versus Monofocal Intraocular Lenses. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2023, 17, 1993–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shymali, O.; McAlinden, C.; Alio Del Barrio, J.L.; Canto-Cerdan, M.; Alio, J.L. Patients’ dissatisfaction with multifocal intraocular lenses managed by exchange with other multifocal lenses of different optical profiles. Eye Vis. 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.W.; Hou, Y.C. Late intraocular lens exchange in dissatisfied patients with multifocal intraocular lens implantation. Taiwan. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 12, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shymali, O.; Alio Del Barrio, J.L.; McAlinden, C.; Canto, M.; Primavera, L.; Alio, J.L. Multifocal intraocular lens exchange to monofocal for the management of neuroadaptation failure. Eye Vis. 2022, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.J.; Sajjad, A.; Montes de Oca, I.; Koch, D.D.; Wang, L.; Weikert, M.P.; Al-Mohtaseb, Z.N. Refractive outcomes after multifocal intraocular lens exchange. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2017, 43, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Manufacturer | Technology | Pupil Dependent | Add Power Diopter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mplus LS-313 MF30 | Oculentis, Berlin, Germany | refractive | no | +3.00 D |

| M-flex | Rayner, Worthing, UK | refractive | no | +3.00 D |

| Tecnis ZM900 | Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, US | Diffractive | yes | +3.00 D |

| Tecnis ZMB100 | Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, US | Diffractive | yes | +2.75 D |

| Acriva Trinova | VSY-Biotechnology, Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany | diffractive | yes | +3.00 D/trifocal/+1.50 D |

| FineVision HP | BVI Medical, Waltham, US | diffractive | yes | +3.50 D/trifocal/+1.75 D |

| AT LISA tri 839 MP | Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany | diffractive | yes | +3.33 D/trifocal/+1.66 D |

| AT Elena 841P | Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany | diffractive | yes | +3.33 D/trifocal/+1.66 D |

| PanOptix TFNT00 IOL | Alcon, Fort Worth, US | Diffractive; enlightened technology | no | +3.25 D/trifocal/+2.17 D |

| Tecnis Synergy | Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, US | Hybrid: combines extended-depth-of-focus (EDOF) optics with multifocal diffractive elements to deliver a continuous range of vision from distance through intermediate to near | yes | Enhanced depth of field |

| Tecnis Odyssey | Johnson & Johnson. New Brunswick, US | Diffractive: a novel nonparabolic diffractive profile, with nonuniform distribution of smoother, more rounded echelettes | no | Not disclosed |

| Model | Manufacturer | Technology | Pupil Dependence | Add Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mini Well Ready | SIFI, Medtech, Aci S. Antonio, Italy | Refractive; Three optical zones: an outer monofocal zone, a 1.80 mm inner zone with positive spherical aberration for intermediate focus, and a 3.00 mm middle zone with negative spherical aberration to enhance near focus. | Yes | +3.00 D |

| Lentis Comfort | Teleon Surgical, Spankeren, Netherlands | Refractive; a rotationally asymmetric multifocal IOL with +1.50 D near addition | No | +1.50 D |

| Acunex Vario | Teleon Surgical, Spankeren, Netherlands | Refractive; a rotationally asymmetric multifocal IOL with +1.50 D near addition | unknown | +1.50 D |

| IC-8 | AcuFocus, Irvine, US | Pinhole Effect; A 3.23 mm black annular mask made of polyvinylidene difluoride and carbon nanoparticles blocks defocused light, while a central 1.36 mm clear aperture permits paraxial rays, producing an EDOF effect. | No | +3.00 D |

| AT LARA 829 MP | Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany | Diffractive; a continuous diffractive surface profile from intermediate to distance focal points | Yes | 0.95 D, +1.90 D |

| Symfony ZXR00 | Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, US | Diffractive; a biconvex, wavefront-optimized anterior aspheric surface (−0.27 μm) combined with a posterior achromatic diffractive pattern utilizing an echelette design for enhanced optical performance. | Yes | +1.75 D |

| FineVision Triumf | PhysIOL, Liège, Belgium | Diffractive; The design integrates two bifocal diffractive grating elements—one optimized for distance and near vision (+3.50 D add), and the other for distance and intermediate vision (+1.75 D add)—to enhance visual performance across multiple ranges | Yes | +1.75 D, +3.50 D |

| Lucidis | SAV-IOL SA, Neuchâtel, Switzerland | Refractive; The 1 mm central aspheric zone functions as an axicon, generating a Bessel beam that produces a continuous range of focal fields, enabling seamless vision from intermediate to near distances | Yes | +3.00 D |

| EDEN | SAV-IOL SA, Neuchâtel, Switzerland | Refractive/Diffractive; This lens features a hybrid refractive-diffractive design: a 1 mm central aspheric zone enhances near and intermediate vision, encircled by a 3.5 mm diffractive zone for near and distance focus, and a 6 mm outer refractive zone dedicated to distance vision. | Yes | +3.00 D |

| Harmonis | SAV-IOL SA, Neuchâtel, Switzerland | Refractive/Diffractive; This lens features a hybrid refractive-diffractive design: a 1.5 mm central aspheric zone enhances near and intermediate vision, encircled by a 3.7 mm diffractive zone for near and distance focus, and a 6 mm outer refractive zone dedicated to distance vision. | possible | +2.50 to +3.50 D |

| EyHance ICB00 | Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, US | Refractive monofocal EDOF; incorporates a small central plateau that induces a localized refractive power change, while its anterior surface features an aberration-correcting curvature with negative primary spherical aberration. | Yes | +1.50 D |

| AE2UV/ZOE | Eyebright/Ophthalmo Pro GmbH, St. Ingbert, Germany | Refractive monofocal EDOF; A high-order aspheric surface enhances intermediate vision by introducing elevated spherical aberration at the IOL center, which progressively diminishes toward the periphery. | possible | +0.75 to 1.00 D |

| Synthesis PLUS | Cutting Edge, Montpellier, France | Refractive monofocal EDOF; a combination of primary and secondary SAs of opposite signs promoting an increase of the depth of field | possible | +1.50 D |

| Vivity DFT015 | Alcon, Fort Worth, US | Refractive monofocal EDOF; nondiffractive X-WAVE technology which stretches and shifts light | No | +1.50 D |

| LuxSmart | Bausch & Lomb, Vaughan, Canada | Refractive; a combination of 4th and 6th orders of SA of opposite sign | possible | +1.75 D |

| RayOne EMV | Rayner, Worthing, UK | Refractive monovision; an increased positive SA to enhance the depth of focus, while the lens outer periphery behaves aberration-neutral | No | Up to 2.25 D EDOF with 1.00 D offset |

| PureSee | Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, US | Refractive; a combination of 4th and 6th orders of SA of opposite sign | possible | +1.75 diopters at the spectacle plane (2.2 D at the IOL plane) |

| Galaxy | Rayner, Worthing, UK | Spiral optic design increased depth of focus | less pupil dependency | Approximately 4 D range of 0.2 logMAR or better near vision |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Park, C.Y. Factors Affecting Postoperative Satisfaction After Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lens. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010336

Park CY. Factors Affecting Postoperative Satisfaction After Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lens. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):336. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010336

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Choul Yong. 2026. "Factors Affecting Postoperative Satisfaction After Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lens" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010336

APA StylePark, C. Y. (2026). Factors Affecting Postoperative Satisfaction After Presbyopia-Correcting Intraocular Lens. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010336