Postoperative Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Versus Conventional Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Within an ERACS Protocol: A Matched Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

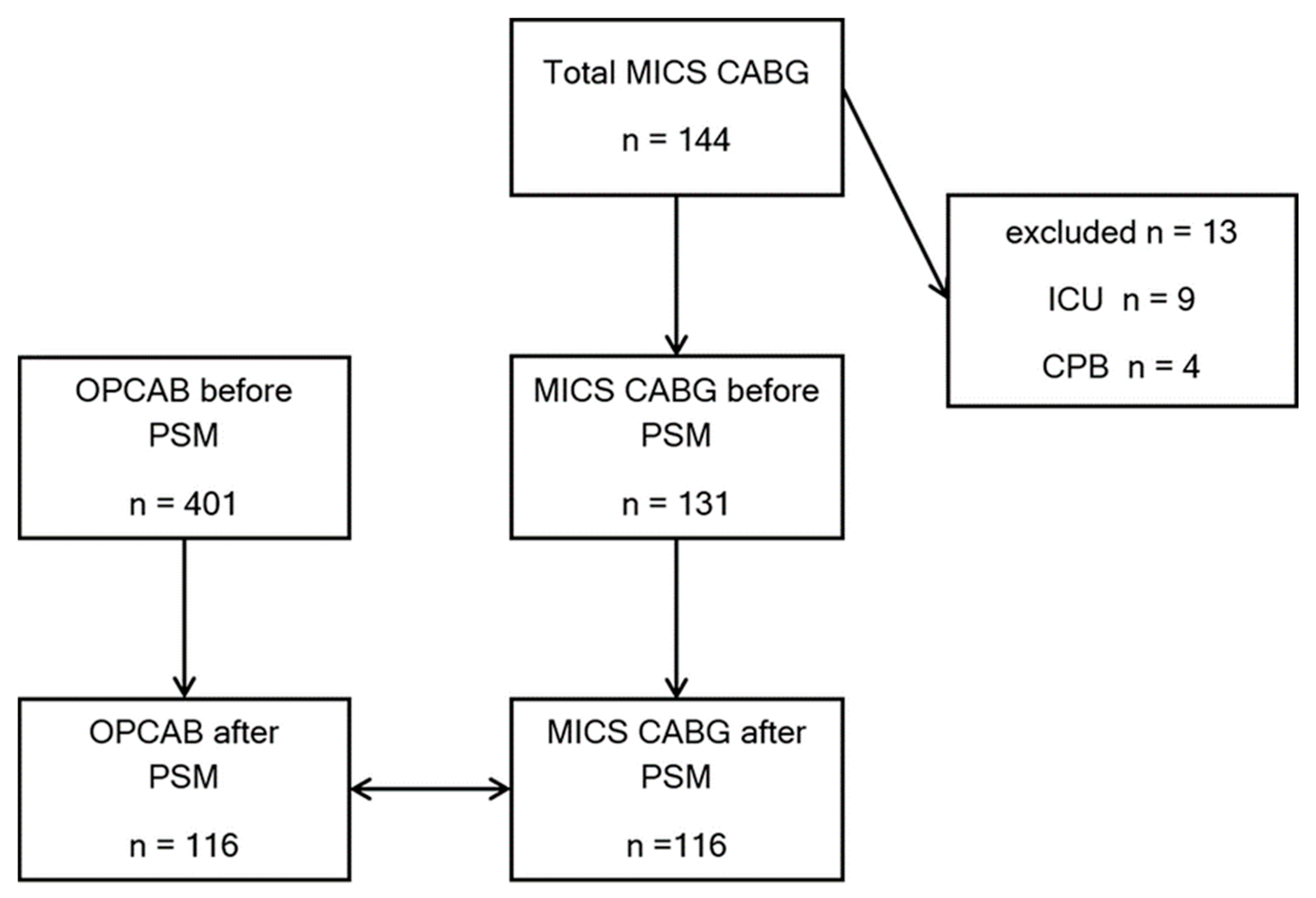

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Endpoints

2.4. Anesthetic Management

2.5. Surgical Approach Selection and Operative Technique

2.6. PACU Management

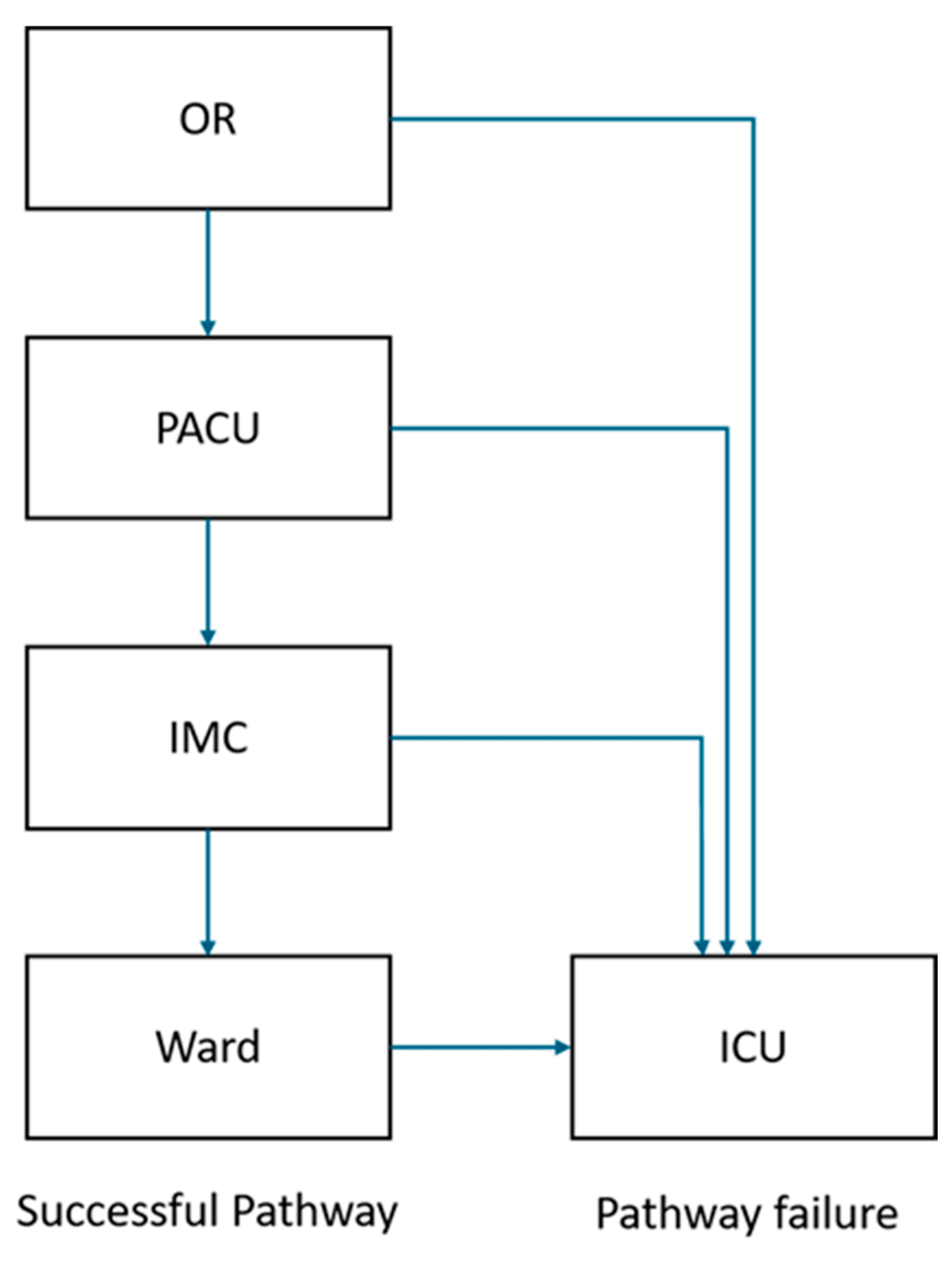

2.7. ERACS Program

2.8. Data Collection

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MICS-CABG | Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting |

| OPCAB | Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass |

| ERACS | Enhanced Recovery after Cardiac Surgery |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary Bypass |

| SLV | Single Lung Ventilation |

References

- St John, A.; Caturegli, I.; Kubicki, N.S.; Kavic, S.M. The Rise of Minimally Invasive Surgery: 16 Year Analysis of the Progressive Replacement of Open Surgery with Laparoscopy. JSLS J. Soc. Laparosc. Robot. Surg. 2020, 24, e2020.00076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinn, J.T., Jr.; Usman, S.; Lapierre, H.; Pothula, V.R.; Mesana, T.G.; Ruel, M. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting: Dual-center experience in 450 consecutive patients. Circulation 2009, 120, S78–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, H.; Chan, V.; Sohmer, B.; Mesana, T.G.; Ruel, M. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting via a small thoracotomy versus off-pump: A case-matched study. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011, 40, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, C.A.; Pike, K.; Angelini, G.D.; Reeves, B.C.; Glauber, M.; Ferrarini, M.; Murphy, G.J. An open randomized controlled trial of median sternotomy versus anterolateral left thoracotomy on morbidity and health care resource use in patients having off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: The Sternotomy Versus Thoracotomy (STET) trial. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2013, 146, 306–316.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruel, M.; Shariff, M.A.; Lapierre, H.; Goyal, N.; Dennie, C.; Sadel, S.M.; Sohmer, B.; McGinn, J.T., Jr. Results of the Minimally Invasive Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Angiographic Patency Study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 147, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehi Hassanabad, A.; Kang, J.; Maitland, A.; Adams, C.; Kent, W.D.T. Review of Contemporary Techniques for Minimally Invasive Coronary Revascularization. Innovations 2021, 16, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.H.; Wells, G.A.; Glineur, D.; Fortier, J.; Davierwala, P.M.; Kikuchi, K.; Lemma, M.G.; Mishra, Y.K.; McGinn, J.; Ramchandani, M.; et al. Minimally Invasive coronary surgery compared to STernotomy coronary artery bypass grafting: The MIST trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2019, 78, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ender, J.; Borger, M.A.; Scholz, M.; Funkat, A.K.; Anwar, N.; Sommer, M.; Mohr, F.W.; Fassl, J. Cardiac surgery fast-track treatment in a postanesthetic care unit: Six-month results of the Leipzig fast-track concept. Anesthesiology 2008, 109, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, D.T.; Ben Ali, W.; Williams, J.B.; Perrault, L.P.; Reddy, V.S.; Arora, R.C.; Roselli, E.E.; Khoynezhad, A.; Gerdisch, M.; Levy, J.H.; et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Cardiac Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society Recommendations. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.C.; Crisafi, C.; Alvarez, A.; Arora, R.C.; Brindle, M.E.; Chatterjee, S.; Ender, J.; Fletcher, N.; Gregory, A.J.; Gunaydin, S.; et al. Perioperative Care in Cardiac Surgery: A Joint Consensus Statement by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Cardiac Society, ERAS International Society, and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2024, 117, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verevkin, A.; Dashkevich, A.; Gadelkarim, I.; Shaqu, R.; Otto, W.; Sgouropoulou, S.; Ender, J.; Kiefer, P.; Borger, M.A. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting via left anterior minithoracotomy: Setup, results, and evolution of a new surgical procedure. JTCVS Tech. 2025, 29, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, J.S.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Bischoff, J.M.; Bittl, J.A.; Cohen, M.G.; DiMaio, J.M.; Don, C.W.; et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e18–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Yoo, K.J.; Youn, Y.N. Transit-Time Flow Measurement and Outcomes in Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Patients. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2023, 35, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhary, W.; Lindner, J.; Sgouropoulou, S.; Eibel, S.; Probst, S.; Scholz, M.; Ender, J. Independent Risk Factors for Fast-Track Failure Using a Predefined Fast-Track Protocol in Preselected Cardiac Surgery Patients. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2015, 29, 1461–1465, Erratum in J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2017, 31, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasheminejad, E.; Flo Forner, A.; Meineri, M.; Ender, J.; Zakhary, W. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting Prophylaxis in Fast-Track Cardiac Anesthesia: A Patient Matched Retrospective before and after Study. Int. J. Anesthesiol. Pain Med. 2022, 8, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Zakhary, W.Z.A.; Turton, E.W.; Flo Forner, A.; von Aspern, K.; Borger, M.A.; Ender, J.K. A comparison of sufentanil vs. remifentanil in fast-track cardiac surgery patients. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teman, N.R.; Hawkins, R.B.; Charles, E.J.; Mehaffey, J.H.; Speir, A.M.; Quader, M.A.; Ailawadi, G.; Investigators for the Virginia Cardiac Services Quality Initiative. Minimally Invasive vs Open Coronary Surgery: A Multi-Institutional Analysis of Cost and Outcomes. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 111, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabindranauth, P.; Burns, J.G.; Vessey, T.T.; Mathiason, M.A.; Kallies, K.J.; Paramesh, V. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Innovations 2014, 9, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziankou, A.; Ostrovsky, Y. Early and Midterm Results of No-Touch Aorta Multivessel Small Thoracotomy Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: A Propensity Score-Matched Study. Innovations 2015, 10, 258–267; discussion 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Probst, S.; Cech, C.; Haentschel, D.; Scholz, M.; Ender, J. A specialized post anaesthetic care unit improves fast-track management in cardiac surgery: A prospective randomized trial. Crit. Care 2014, 18, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grutzner, H.; Flo Forner, A.; Meineri, M.; Janai, A.; Ender, J.; Zakhary, W.Z.A. A Comparison of Patients Undergoing On- vs. Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery Managed with a Fast-Track Protocol. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambala, S.; Mishra, Y.K.; Ruel, M. Less invasive multivessel coronary artery bypass grafting: Now is the time. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2021, 36, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poston, R.S.; Tran, R.; Collins, M.; Reynolds, M.; Connerney, I.; Reicher, B.; Zimrin, D.; Griffith, B.P.; Bartlett, S.T. Comparison of economic and patient outcomes with minimally invasive versus traditional off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting techniques. Ann. Surg. 2008, 248, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Extubation Criteria |

|---|---|

| Consciousness | Fully awake and alert, no neurological deficit |

| Hemodynamic Stability | Stable without inotropic support |

| Core Temperature | ≥36 °C |

| Arterial Blood Gases | PaO2 ≥ 100 mmHg, PaCO2 ≤ 42 mmHg on FiO2 0.40 |

| CentralVenous Oxygen Saturation (ScvO2) | >65% |

| Ventilation | Adequate tidal volumes with pressure support of 8 cmH2O and PEEP of 5 cmH2O |

| Chest drain output | <100 mL/h |

| Serum lactate | Within normal range |

| ECG and Chest X-ray | No new ischemic changes or pulmonary complications |

| Parameter | Transfer Criteria |

|---|---|

| Consciousness | Fully awake, no neurological deficit |

| Hemodynamic Stability | Stable without significant support |

| Inotropic Support | None or minimal |

| Arterial blood gases | PaO2 > 90 mmHg, PaCO2 < 46 mmHg |

| Oxygen Saturation (SpO2) | >96% with 2–6 L/min O2 |

| Urinary output | >0.5 mL/kg/h |

| Chest drain output | <50 mL/h, serous |

| Serum Lactate | Normal |

| Central Venous Oxygen Saturation (ScvO2) | >60% |

| Cardiac Enzymes & Chest X-ray | No findings requiring intervention |

| Pain Control | NRS < 4 |

| MICS-CABG (n = 116) | OPCAB (n = 116) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.72 ± 8.93 | 64.69 ± 9.56 | 0.983 |

| Female sex | 22 (19.0%) | 18 (15.5%) | 0.602 |

| Height, cm | 171.79 ± 8.24 | 174.01 ± 8.29 | 0.042 |

| Weight, kg | 81.31 ± 15.84 | 82.78 ± 13.53 | 0.449 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.48 ± 4.63 | 27.32 ± 4.12 | 0.788 |

| LVEF, % | 55.34 ± 11.04 | 55.34 ± 7.99 | 0.994 |

| History of MI | 40 (34.5%) | 41 (35.3%) | 0.999 |

| EuroScore II | 1.66 ± 1.67 | 1.53 ± 1.15 | 0.477 |

| ASA II | 3 (2.6%) | 13 (11.2%) | 0.017 |

| ASA III | 106 (91.4%) | 98 (84.5%) | 0.158 |

| ASA IV | 7 (6.0%) | 5 (4.3%) | 0.766 |

| NYHA I | 17 (14.7%) | 14 (12.1%) | 0.699 |

| NYHA II | 51 (44.0%) | 66 (56.9%) | 0.066 |

| NYHA III | 48 (41.4%) | 35 (30.2%) | 0.100 |

| NYHA IV | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.999 |

| Hypertension | 97 (83.6%) | 103 (88.8%) | 0.341 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 14 (12.1%) | 5 (4.3%) | 0.055 |

| COPD | 5 (4.3%) | 6 (5.2%) | 0.999 |

| CNS disease | 9 (7.8%) | 9 (7.8%) | 0.999 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (7.8%) | 13 (11.2%) | 0.501 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (37.9%) | 35 (30.2%) | 0.267 |

| Smoker | 28 (24.1%) | 27 (23.3%) | 0.999 |

| Urgency | 20 (17.2%) | 17 (14.7%) | 0.719 |

| Redo surgery | 3 (2.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.621 |

| Preoperative arrhythmia | 10 (8.6%) | 9 (7.8%) | 0.999 |

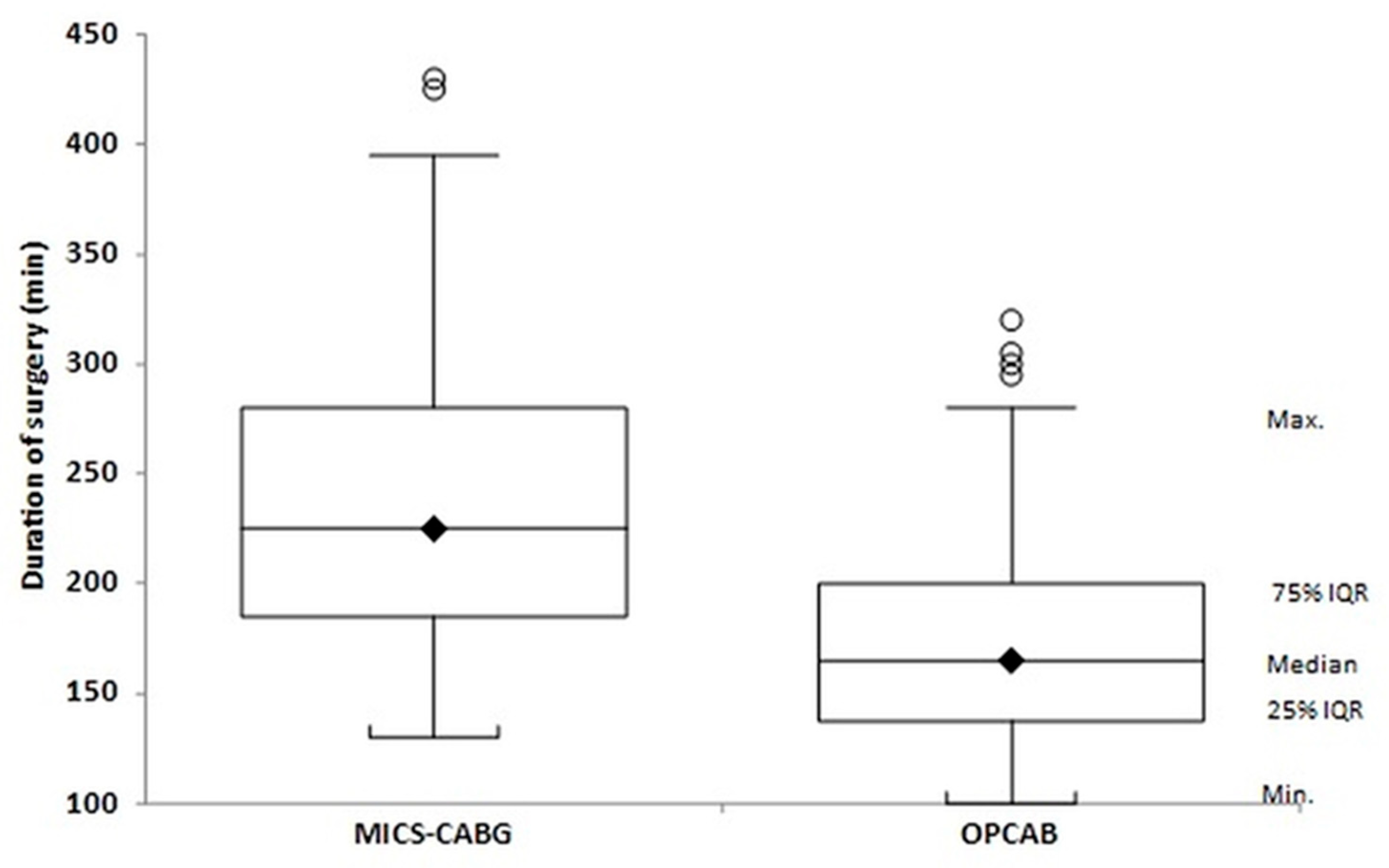

| Operative duration, min | 238.88 ± 65.07; 225 [185–280] | 174.96 ± 48.20; 165 [139–200] | <0.001 |

| Number of grafts | 2.31 ± 0.64; 2 [2–3] | 2.33 ± 0.49; 2 [2–3] | 0.817 |

| MICS-CABG (n = 116) | OPCAB (n = 116) | Effect Size (MD/OR) | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventilation time, min | 112.20 ± 56.91; 100 [75–136] | 116.87 ± 64.74; 105 [75–145] | 4.67 | −12.42 to 21.75 | 0.590 |

| PACU LOS, min | 262.08 ± 75.69; 258 [214–318] | 265.04 ± 87.24; 250 [210–303] | 2.96 | −19.91 to 25.83 | 0.798 |

| Unplanned ICU transfer | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (2.6%) | 3.08 | 0.32 to 30.06 | 0.369 |

| Hospital LOS, days | 8.70 ± 3.97; 7 [7–9] | 8.55 ± 4.09; 7 [6–9] | −0.15 | −1.19 to 0.90 | 0.782 |

| MICS-CABG (n = 116) | OPCAB (n = 116) | Effect (MD/OR) | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pericardial effusion | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3.03 | 0.12 to 75.05 | 0.999 |

| Myocardial infarction | 18 (15.5%) | 13 (11.2%) | 0.69 | 0.32 to 1.48 | 0.440 |

| Arrhythmia | 38 (32.8%) | 35 (30.2%) | 0.89 | 0.51 to 1.54 | 0.777 |

| Delirium | 6 (5.2%) | 9 (7.8%) | 1.54 | 0.53 to 4.48 | 0.593 |

| Stroke | 3 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.14 | 0.01 to 2.72 | 0.246 |

| Renal complications | 8 (6.9%) | 15 (12.9%) | 2.00 | 0.82 to 4.93 | 0.187 |

| Pulmonary complications | 17 (14.7%) | 14 (12.1%) | 0.80 | 0.37 to 1.71 | 0.699 |

| Significant bleeding | 35 (30.2%) | 27 (23.3%) | 0.70 | 0.39 to 1.26 | 0.299 |

| RBC transfusion (patients) | 17 (14.6%) | 28 (24.1%) | 0.54 | 0.28 to 1.05 | 0.096 |

| RBC units, all patients | 0.40 ± 1.43 | 0.68 ± 1.41 | −0.27 | −0.62 to 0.07 | 0.120 |

| RBC units, transfused only | 2.76 ± 2.81 | 2.82 ± 1.51 | −0.71 | −1.57 to 0.16 | 0.103 |

| Re-exploration | 4 (3.4%) | 2 (1.7%) | 0.49 | 0.09 to 2.74 | 0.683 |

| PONV | 5 (4.3%) | 3 (2.6%) | 0.59 | 0.14 to 2.53 | 0.721 |

| NRS pain score | 2.03 ± 0.95; 2 [2–2] | 1.90 ± 1.04; 2 [1–2] | −0.12 | −0.38 to 0.14 | 0.347 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.20 | 0.01 to 4.14 | 0.497 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saad, M.; Gadelkarim, I.; Borger, M.; Meineri, M.; Janai, A.; Sgouropoulou, S.; Ender, J.; Zakhary, W. Postoperative Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Versus Conventional Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Within an ERACS Protocol: A Matched Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010328

Saad M, Gadelkarim I, Borger M, Meineri M, Janai A, Sgouropoulou S, Ender J, Zakhary W. Postoperative Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Versus Conventional Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Within an ERACS Protocol: A Matched Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010328

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaad, Mostafa, Ibrahim Gadelkarim, Michael Borger, Massimiliano Meineri, Aniruddha Janai, Sophia Sgouropoulou, Jörg Ender, and Waseem Zakhary. 2026. "Postoperative Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Versus Conventional Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Within an ERACS Protocol: A Matched Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010328

APA StyleSaad, M., Gadelkarim, I., Borger, M., Meineri, M., Janai, A., Sgouropoulou, S., Ender, J., & Zakhary, W. (2026). Postoperative Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Versus Conventional Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Within an ERACS Protocol: A Matched Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010328