Variability of the Sprint Step Movement Pattern and Its Association with Hamstring Injury Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Procedure

2.3. Hamstring Injury Survey

2.4. Kinematic Analysis of the 50 m Sprint

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

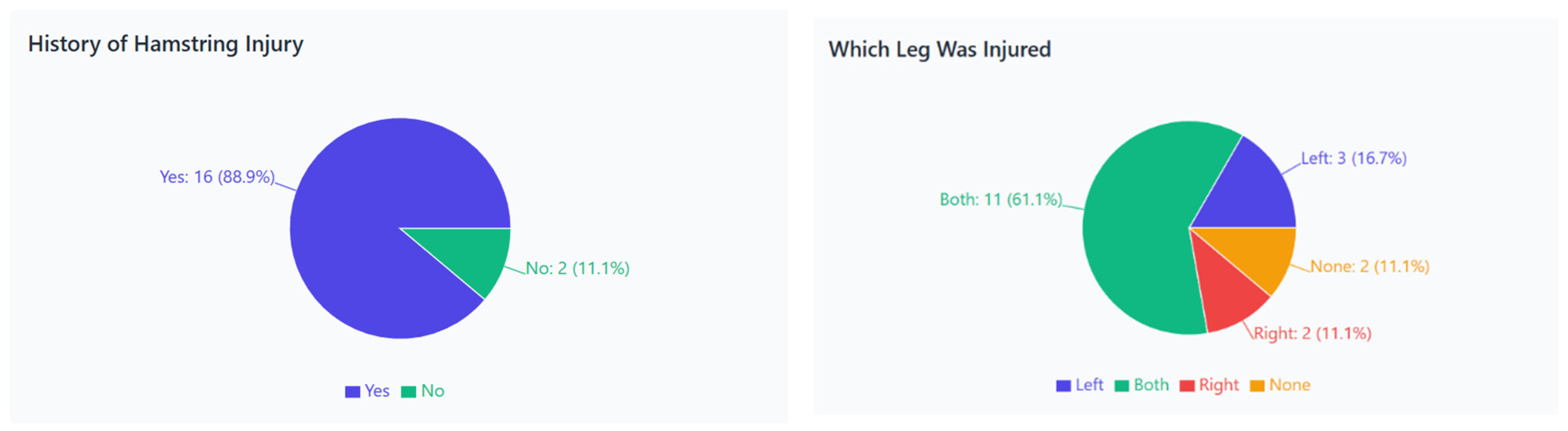

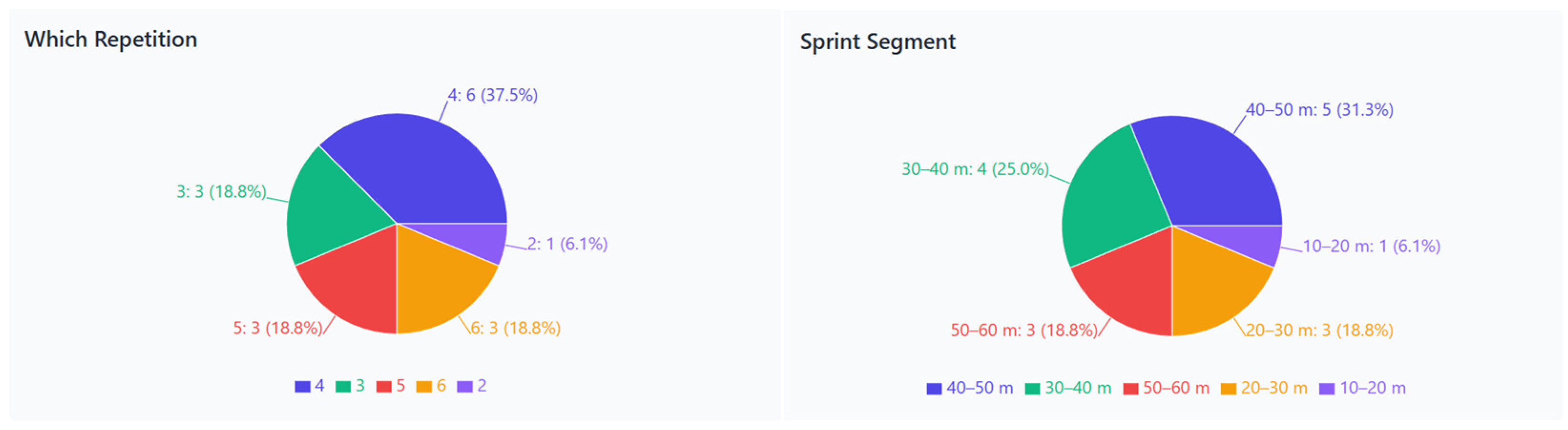

3.1. Survey—Analysis of Key Factors

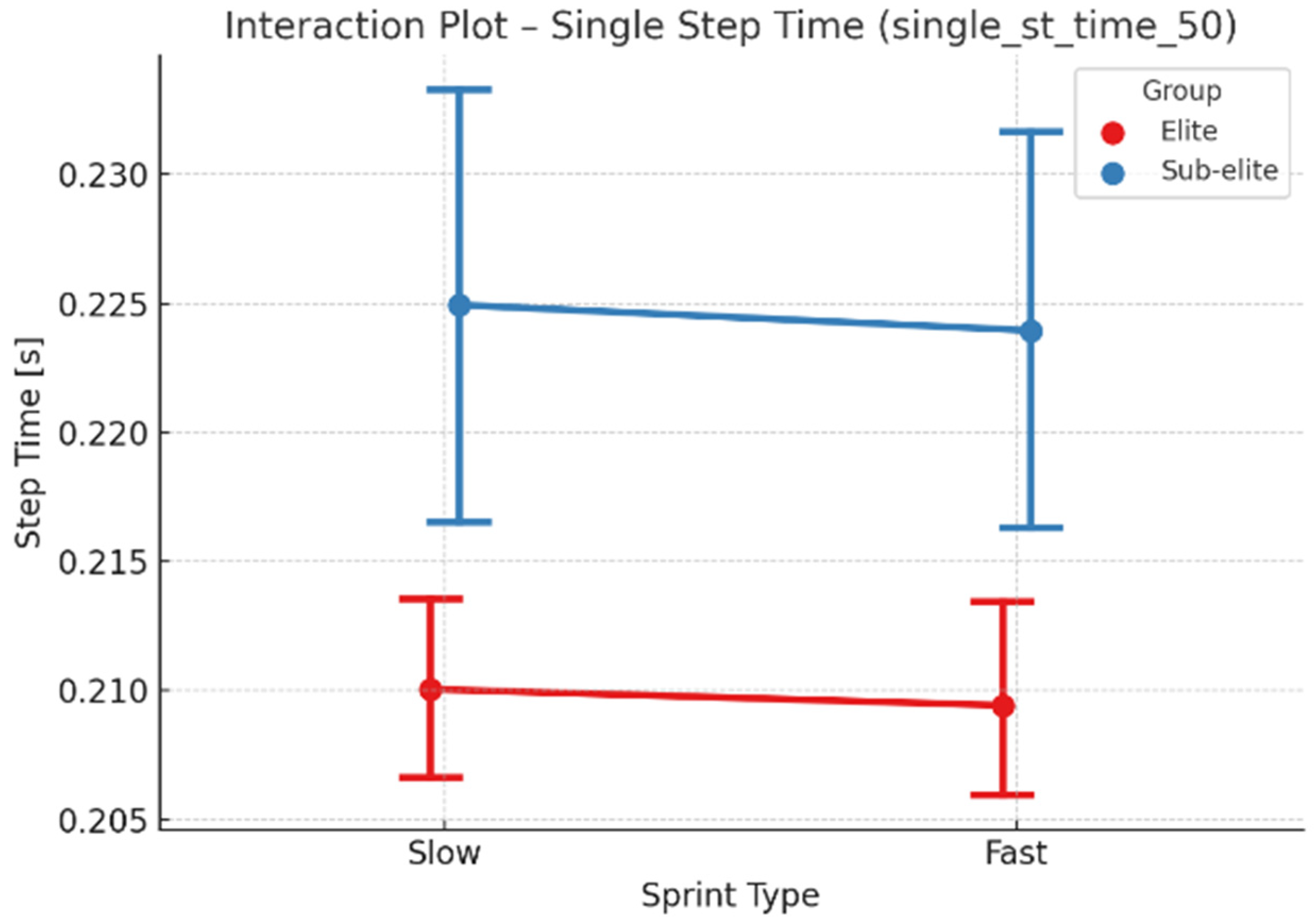

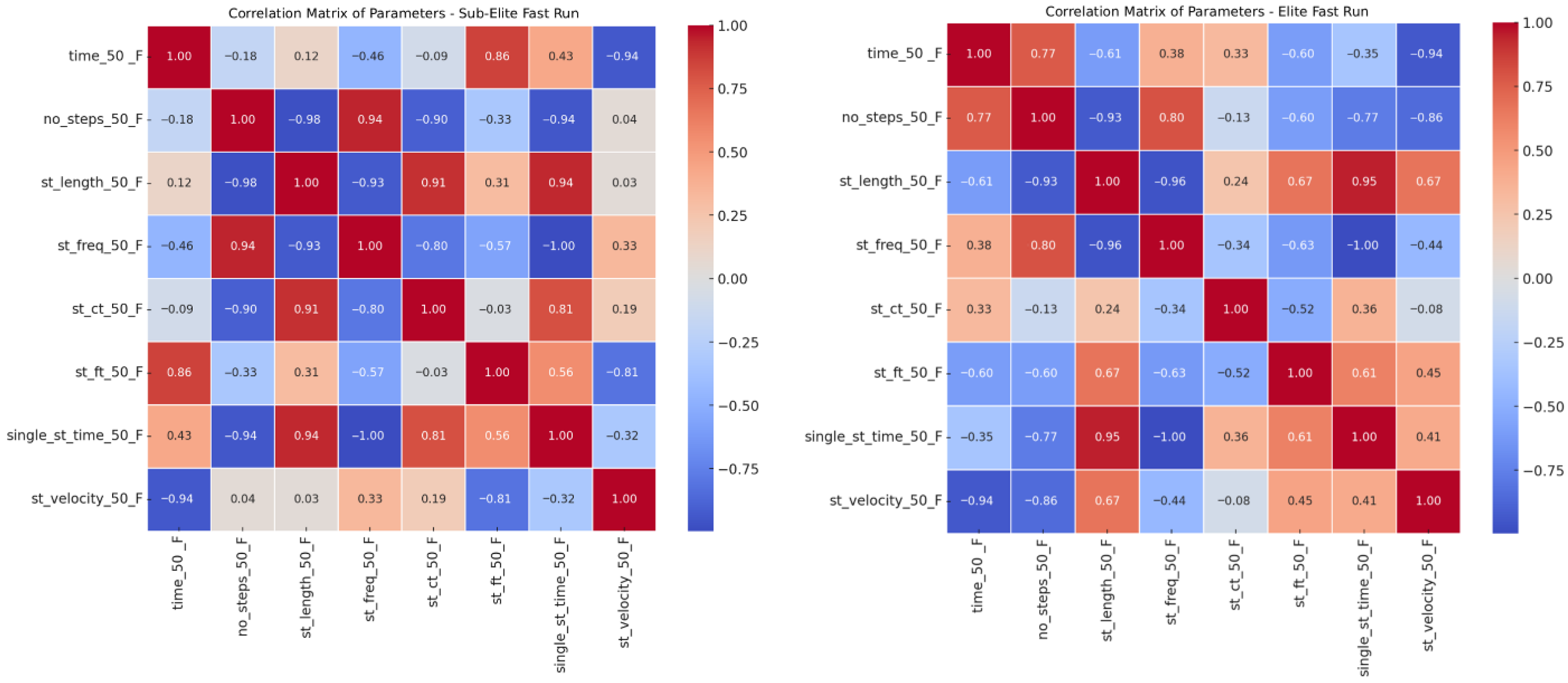

3.2. Kinematic Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions and Implications for Training

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morin, J.B.; Edouard, P.; Samozino, P. Technical ability of force application as a determinant factor of sprint performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyand, P.G.; Sternlight, D.B.; Bellizzi, M.J.; Wright, S. Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces, not more rapid leg movements. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.P.; Marshall, R.N.; McNair, P.J. Relationships between ground reaction force impulse and kinematics of sprint-running acceleration. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Prampero, P.E.; Fusi, S.; Morin, J.B.; Belli, A.; Antonutto, G. Sprint running: A new, energetic approach. J. Exp. Biol. 2005, 208, 2809–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billaut, F.; Basset, F.; Falgairette, G. Muscle coordination changes during intermittent cycling sprints. Neurosci. Lett. 2005, 380, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, V.; Lahti, J.; Castaño Zambudio, A.; Mendiguchia, J.; Jiménez-Reyes, P.; Morin, J.B. Effects of fatigue induced by repeated sprints on sprint biomechanics in football players: Should we look at the group or the individual? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramah, C.; Mendiguchia, J.; Dos Santos, T.; Morin, J.B. Exploring the role of sprint biomechanics in hamstring strain injuries: A current opinion on existing concepts and evidence. Sports Med. 2023, 54, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramah, C.; Rhodes, S.; Clarke-Cornwell, A.; Dos Santos, T.; Morin, J.B.; Mendiguchia, J. Sprint running mechanics are associated with hamstring strain injury: A 6-month prospective cohort study of 126 elite male footballers. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalema, R.N.; Duhig, S.J.; Williams, M.D.; Donaldson, A.; Shield, A.J. Sprinting technique and hamstring strain injuries: A concept mapping study. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2022, 25, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagos, A.; Merchant, A.A.; Kayani, B.; Yasen, A.T.; Fares, S.; Haddad, F.S. Risk factors and injury prevention strategies for hamstring injuries: A narrative review. EFORT Open Rev. 2025, 10, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askling, C.; Tengvar, M.; Saartok, T.; Thorstensson, A. Sports-related hamstring strains—Two cases with different etiologies and injury sites. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2000, 10, 304–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opar, D.A.; Williams, M.D.; Shield, A.J. Hamstring strain injuries: Factors that lead to injury and re-injury. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edouard, P.; Mendiguchia, J.; Guex, K.; Lahti, J.; Prince, C.; Samozino, P. Sprinting: A key piece of the hamstring injury risk management puzzle. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsson, A.; van Hooren, B.; Horvath, C.; Halvorsen, K.A. The mechanism of hamstring injuries: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.; Giorgi, F.; Donati, D. Sprint training for hamstring injury prevention: A scoping review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Higashihara, A.; Shinohara, J.; Hirose, N.; Fukubayashi, T. Estimation of tensile force in the hamstring muscles during overground sprinting. Int. J. Sports Med. 2015, 36, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Schache, A.G.; Dorn, T.W.; Blanch, P.D.; Brown, N.A.T.; Pandy, M.G. Mechanics of the human hamstring muscles during sprinting. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Queen, R.M.; Liu, Y.; Garrett, W.E. Mechanism of hamstring muscle strain injury in sprinting. J. Sport Health Sci. 2017, 6, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, G.; Moreno-Simonet, L.; Cosio, P.L.; Astrella, A.; Fernández, D.; Padullés, X.; Cadefau, J.A.; Padullés, J.M.; Mendiguchia, J. Acute changes in hamstring injury risk factors after a high-volume maximal sprinting session in soccer players. Sports Health 2025, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Murray, E.; Sainsbury, D. The effect of warm-up, static stretching, and dynamic stretching on hamstring flexibility in previously injured subjects. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneally-Dabrowski, C.J.B.; Brown, N.A.T.; Lai, A.K.M.; Perriman, D.; Spratford, W.; Serpell, B.G. Late swing or early stance? A narrative review of hamstring injury mechanisms during high-speed running. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sople, D.; Wilcox, R.B. Dynamic warm-ups play a pivotal role in athletic performance and injury prevention. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2024, 7, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelidis, P.E.; Shan, X.; Otsuka, S.; Yang, C.; Yamagishi, T.; Kawakami, Y. Fatigue-induced changes in hamstrings’ active muscle stiffness: Effect of contraction type and implications for strain injuries. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 123, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, M.; Li, L.; Chen, C.; Wu, X. Stretch could reduce hamstring injury risk during sprinting by right shifting the length-torque curve. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2190–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagahara, R.; Mizutani, M.; Matsuo, A.; Kanehisa, H.; Fukunaga, T. Association of step length and step frequency during sprinting with acceleration and maximum speed performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Mendiguchia, J.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Brughelli, M. Hamstring strain injuries: Are we heading in the right direction? Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, A.; Ono, T.; Kubota, J.; Okuwaki, T.; Fukubayashi, T. Functional differences in the activity of the hamstring muscles with increasing running speed. J. Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumanov, E.S.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Thelen, D.G. Hamstring musculotendon dynamics during stance and swing phases of high-speed running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 39, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Rafiq, M.T.; Ul-Hassan, T.; Sharif, A. Role of warm-up exercise in preventing hamstring injury in sprinters. Rawal Med. J. 2022, 47, 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura, Y.; Sakuma, K.; Sakuraba, K.; Sato, Y. Prevention of hamstring injuries in collegiate sprinters. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2017, 5, 2325967116681524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čoh, M. Differences between the elite and subelite sprinters in kinematic and dynamic determinations of countermovement jump and drop jump. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 3146–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezodis, N.E.; Willwacher, S.; Salo, A.I.T. The biomechanics of the track and field sprint start: A narrative review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1345–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Queen, R.M.; Abbey, A.N.; Liu, Y.; Moorman, C.T.; Garrett, W.E. Hamstring muscle kinematics and activation during overground sprinting. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 3121–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandy, M.G.; Lai, A.K.M.; Schache, A.G.; Lin, Y.C. How muscles maximize performance in accelerated sprinting. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 1882–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiguchia, J.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Myer, G.D. The role of hamstrings in the prevention of hamstring injuries. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 751–763. [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi, A.; Csala, D.; Péter, A.; Finni, T.; Cronin, N.J. High-density electromyography activity in various hamstring exercises. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerone, G.L.; Nicola, R.; Caruso, M.; Rossanigo, R.; Cereatti, A.; Vieira, T.M. Running speed changes the distribution of excitation within the biceps femoris muscle in 80 m sprints. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023, 33, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Guo, C.; Li, H.S.; Liu, H.; Sun, P. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of the effects of different warm-up methods on the acute effects of lower limb explosive strength. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramah, C.; McLeod, P.; Wilson, R. The sprint mechanics assessment score: A qualitative tool for assessing sprint running mechanics associated with lower limb injuries in male and female soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Gurchiek, R.D.; Teplin, Z.; Falisse, A.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. Hamstrings are stretched more and faster during accelerative running compared to speed-matched constant-speed running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2025, 57, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | s | v | Confidence | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −95% | +95% | ||||||||

| 50 m Slow Run Time [s] | Elite | 9 | 5.427 | 0.10 | 1.84 | 5.35 | 5.50 | −3.71 | 0.0019 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 5.627 | 0.13 | 2.31 | 5.53 | 5.73 | |||

| 50 m Fast Run Time [s] | Elite | 9 | 5.351 | 0.11 | 2.06 | 5.27 | 5.44 | −3.49 | 0.0030 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 5.544 | 0.12 | 2.16 | 5.45 | 5.64 | |||

| Number of Steps (Slow) | Elite | 9 | 25.556 | 0.88 | 3.44 | 24.88 | 26.23 | 1.05 | 0.3100 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 24.889 | 1.69 | 6.79 | 23.59 | 26.19 | |||

| Number of Steps (Fast) | Elite | 9 | 25.556 | 1.01 | 3.95 | 24.78 | 26.33 | 1.48 | 0.1572 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 24.778 | 1.20 | 4.84 | 23.85 | 25.70 | |||

| Step Length (Slow) [cm] | Elite | 9 | 191.658 | 6.17 | 3.22 | 186.91 | 196.40 | −1.30 | 0.2107 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 197.344 | 11.54 | 5.85 | 188.48 | 206.21 | |||

| Step Length (Fast) [cm] | Elite | 9 | 192.243 | 7.16 | 3.72 | 186.74 | 197.75 | −1.39 | 0.1831 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 198.144 | 10.51 | 5.30 | 190.06 | 206.23 | |||

| Step Frequency (Slow) [steps/s] | Elite | 9 | 4.781 | 0.13 | 2.72 | 4.68 | 4.88 | 2.93 | 0.0097 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 4.472 | 0.29 | 6.48 | 4.25 | 4.69 | |||

| Step Frequency (Fast) [steps/s] | Elite | 9 | 4.784 | 0.14 | 2.93 | 4.68 | 4.89 | 3.03 | 0.0080 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 4.484 | 0.26 | 5.80 | 4.28 | 4.69 | |||

| Contact Time (Slow) [s] | Elite | 9 | 0.105 | 0.01 | 9.52 | 0.10 | 0.11 | −2.57 | 0.0204 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 0.116 | 0.01 | 8.62 | 0.11 | 0.12 | |||

| Contact Time (Fast) [s] | Elite | 9 | 0.104 | 0.01 | 9.62 | 0.10 | 0.11 | −2.72 | 0.0151 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 0.115 | 0.01 | 8.70 | 0.11 | 0.12 | |||

| Flight Phase (Slow) [s] | Elite | 9 | 0.105 | 0.01 | 9.52 | 0.10 | 0.11 | −1.46 | 0.1642 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 0.109 | 0.01 | 9.17 | 0.10 | 0.12 | |||

| Flight Phase (Fast) [s] | Elite | 9 | 0.105 | 0.01 | 9.52 | 0.10 | 0.11 | −1.05 | 0.3079 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 0.109 | 0.01 | 9.17 | 0.10 | 0.11 | |||

| Single Step Time (Slow) [s] | Elite | 9 | 0.210 | 0.01 | 4.76 | 0.21 | 0.21 | −2.90 | 0.0105 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 0.225 | 0.01 | 4.44 | 0.21 | 0.24 | |||

| Single Step Time (Fast) [s] | Elite | 9 | 0.209 | 0.01 | 4.78 | 0.20 | 0.21 | −3.07 | 0.0073 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 0.224 | 0.01 | 4.46 | 0.21 | 0.23 | |||

| Step Velocity (Slow) [m/s] | Elite | 9 | 9.183 | 0.14 | 1.84 | 9.08 | 9.29 | 4.66 | 0.0003 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 8.807 | 0.20 | 2.31 | 8.65 | 8.96 | |||

| Step Velocity (Fast) [m/s] | Elite | 9 | 9.208 | 0.11 | 2.06 | 9.13 | 9.29 | 4.75 | 0.0002 |

| Sub-elite | 9 | 8.874 | 0.18 | 2.16 | 8.73 | 9.01 | |||

| Parameter | Group Effect (p) | Sprint Type Effect (p) | Interaction (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Running time | 0.0000 | 0.0482 | 0.9191 |

| Number of steps | 0.0892 | 0.8936 | 0.8936 |

| Step length | 0.0658 | 0.8214 | 0.9721 |

| Step frequency | 0.0865 | 0.9868 | 0.8074 |

| Ground contact time | 0.0007 | 0.8127 | 0.9165 |

| Flight phase | 0.0865 | 0.9868 | 0.8074 |

| Single-step time | 0.0002 | 0.8190 | 0.9585 |

| Step velocity | 0.0000 | 0.3908 | 0.7021 |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Mean Difference | Lower CI | Upper CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elite_Fast | Elite_Slow | 0.0006 | −0.0128 | 0.0140 | 0.9993 |

| Elite_Fast | Sub-elite_Fast | 0.0145 | 0.0011 | 0.0279 | 0.0293 |

| Elite_Fast | Sub-elite_Slow | 0.0155 | 0.0021 | 0.0289 | 0.0180 |

| Elite_Slow | Sub-elite_Fast | 0.0139 | 0.0005 | 0.0273 | 0.0393 |

| Elite_Slow | Sub-elite_Slow | 0.0149 | 0.0015 | 0.0283 | 0.0245 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jopek, M.; Krzysztofik, M.; Mroczek, D.; Zajac, A.; Mackala, K. Variability of the Sprint Step Movement Pattern and Its Association with Hamstring Injury Risk. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010281

Jopek M, Krzysztofik M, Mroczek D, Zajac A, Mackala K. Variability of the Sprint Step Movement Pattern and Its Association with Hamstring Injury Risk. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010281

Chicago/Turabian StyleJopek, Mateusz, Michal Krzysztofik, Dariusz Mroczek, Adam Zajac, and Krzysztof Mackala. 2026. "Variability of the Sprint Step Movement Pattern and Its Association with Hamstring Injury Risk" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010281

APA StyleJopek, M., Krzysztofik, M., Mroczek, D., Zajac, A., & Mackala, K. (2026). Variability of the Sprint Step Movement Pattern and Its Association with Hamstring Injury Risk. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010281