Maxillofacial Fractures in Southern Hungary: A 15-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of 1948 Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

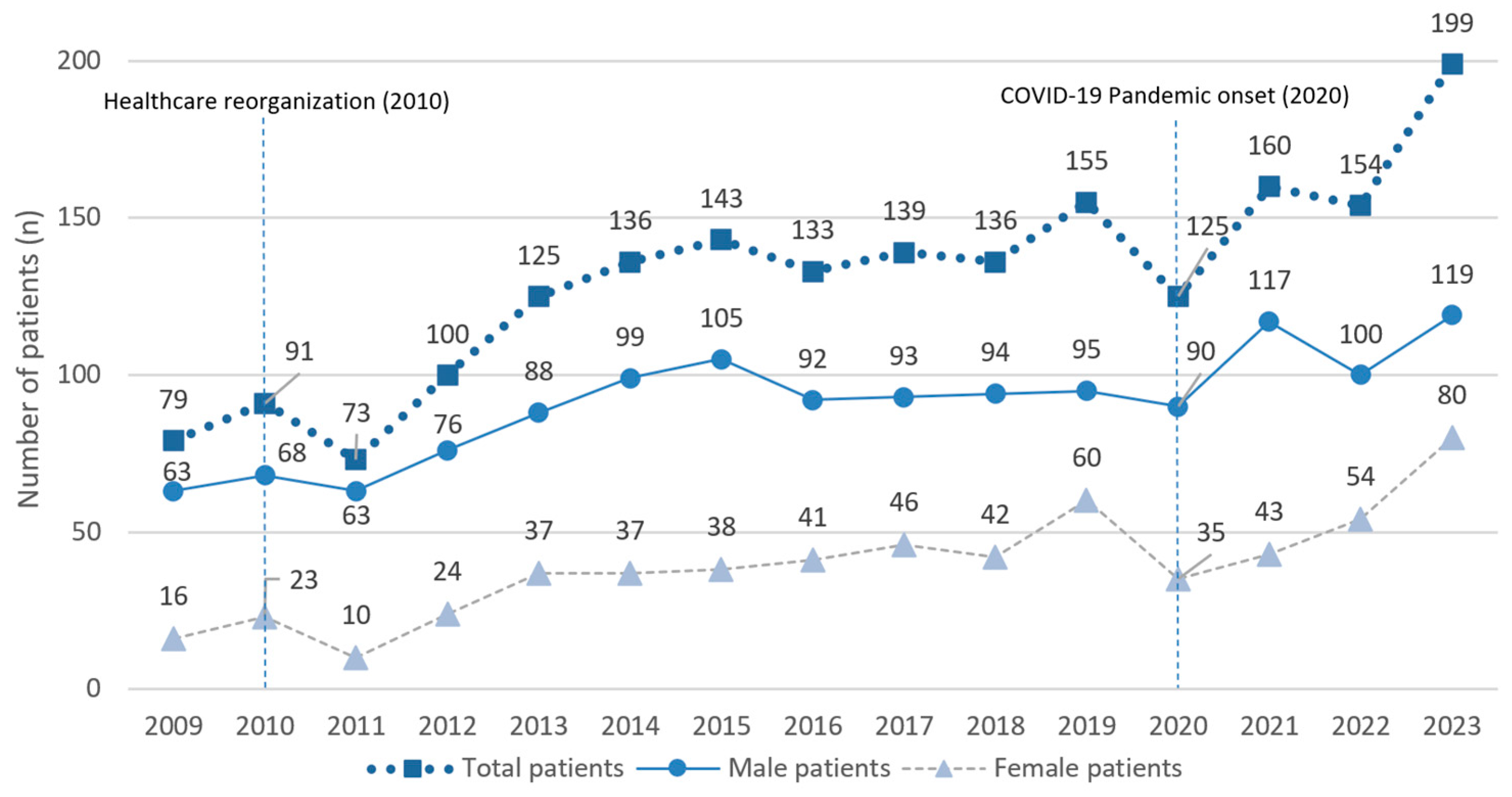

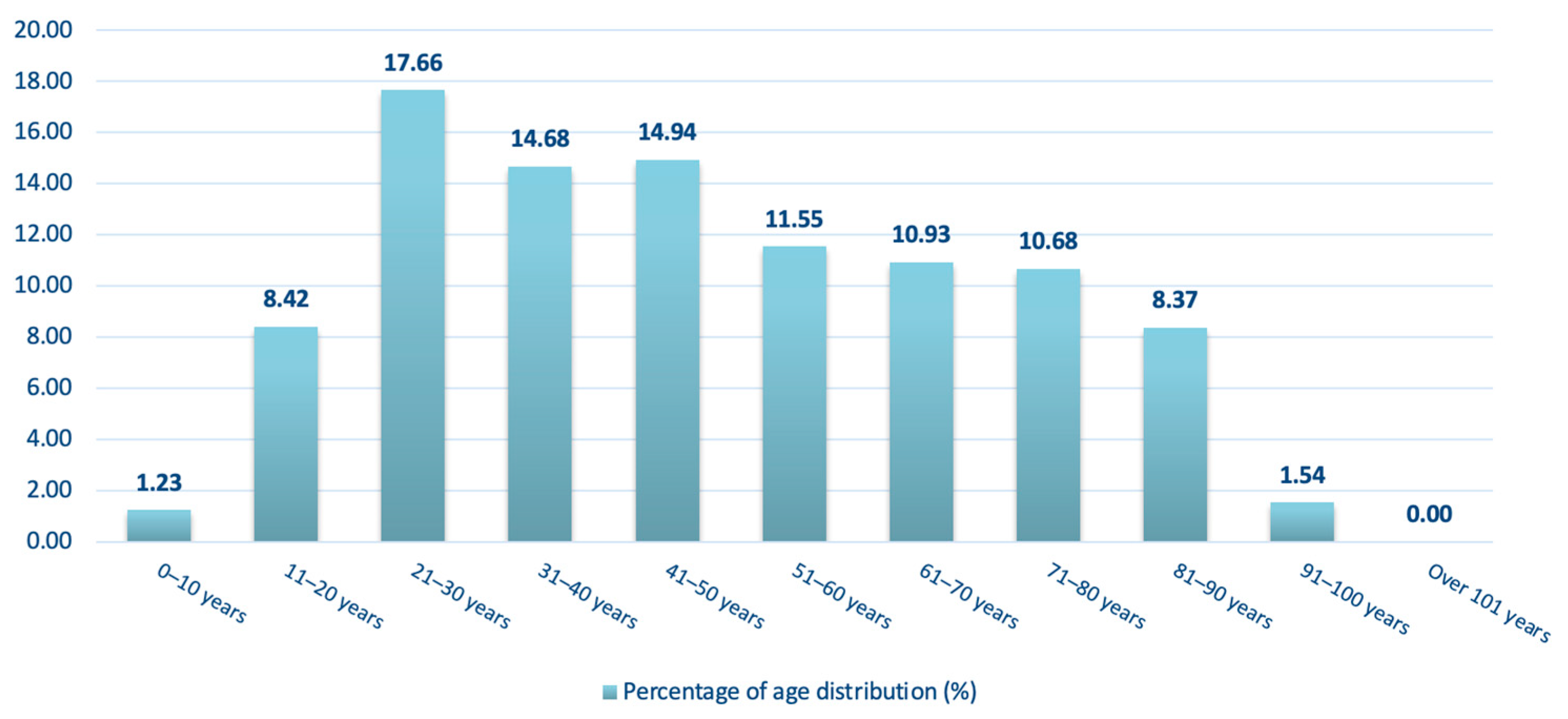

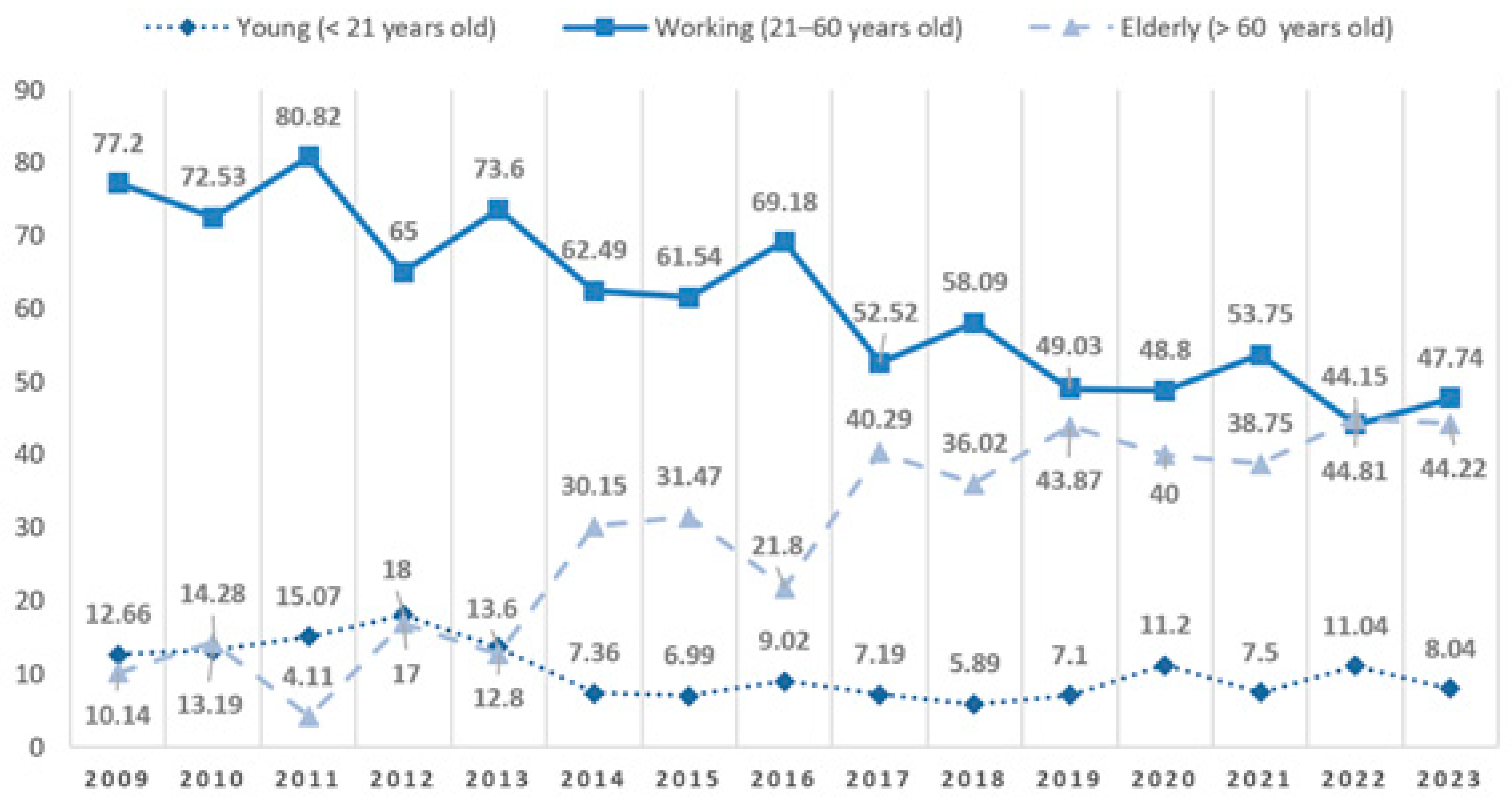

3.1. Distribution of Patients by Year, Sex, and Age

3.2. Occurrence of Maxillofacial Injuries and Days of the Week

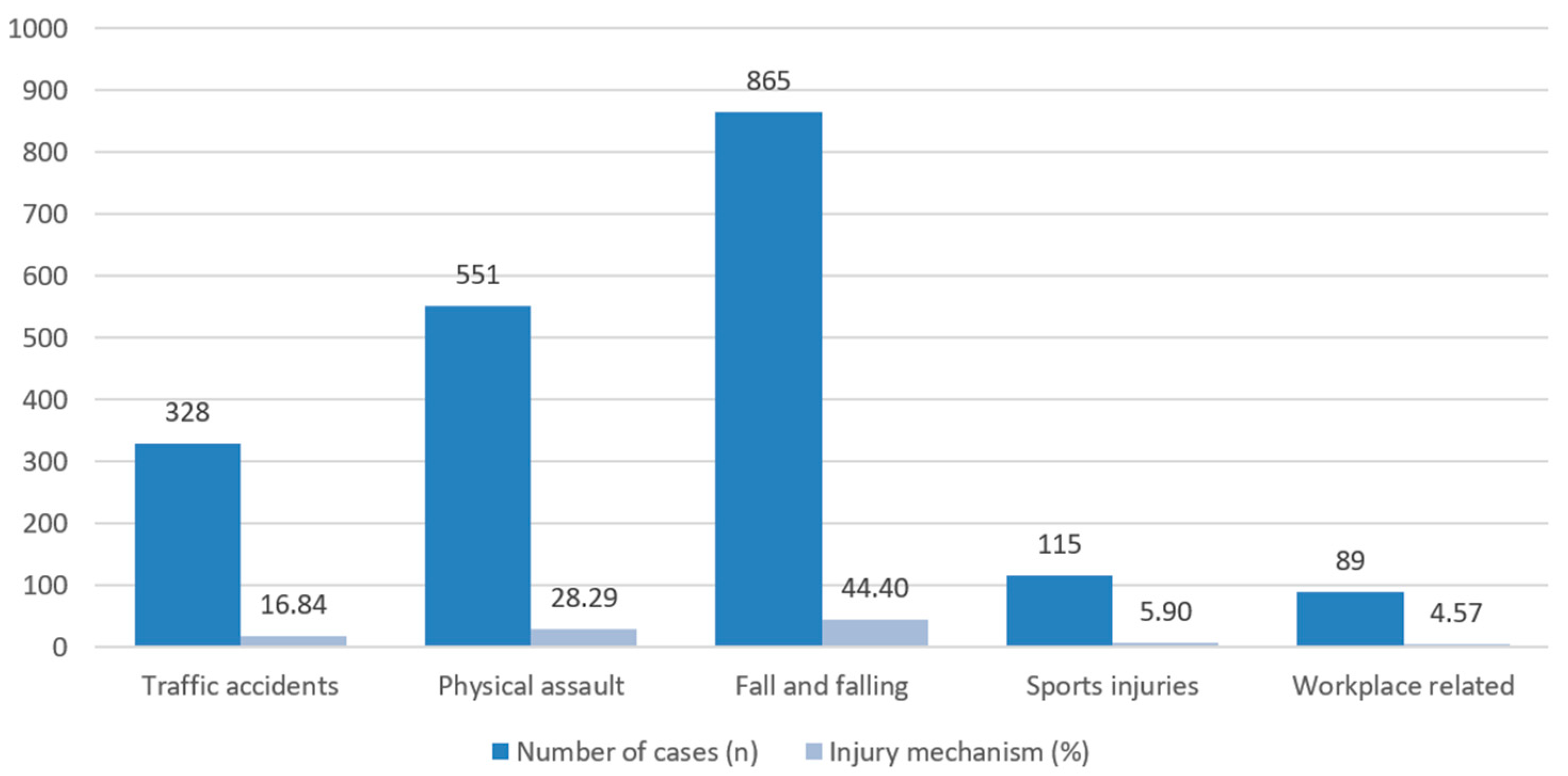

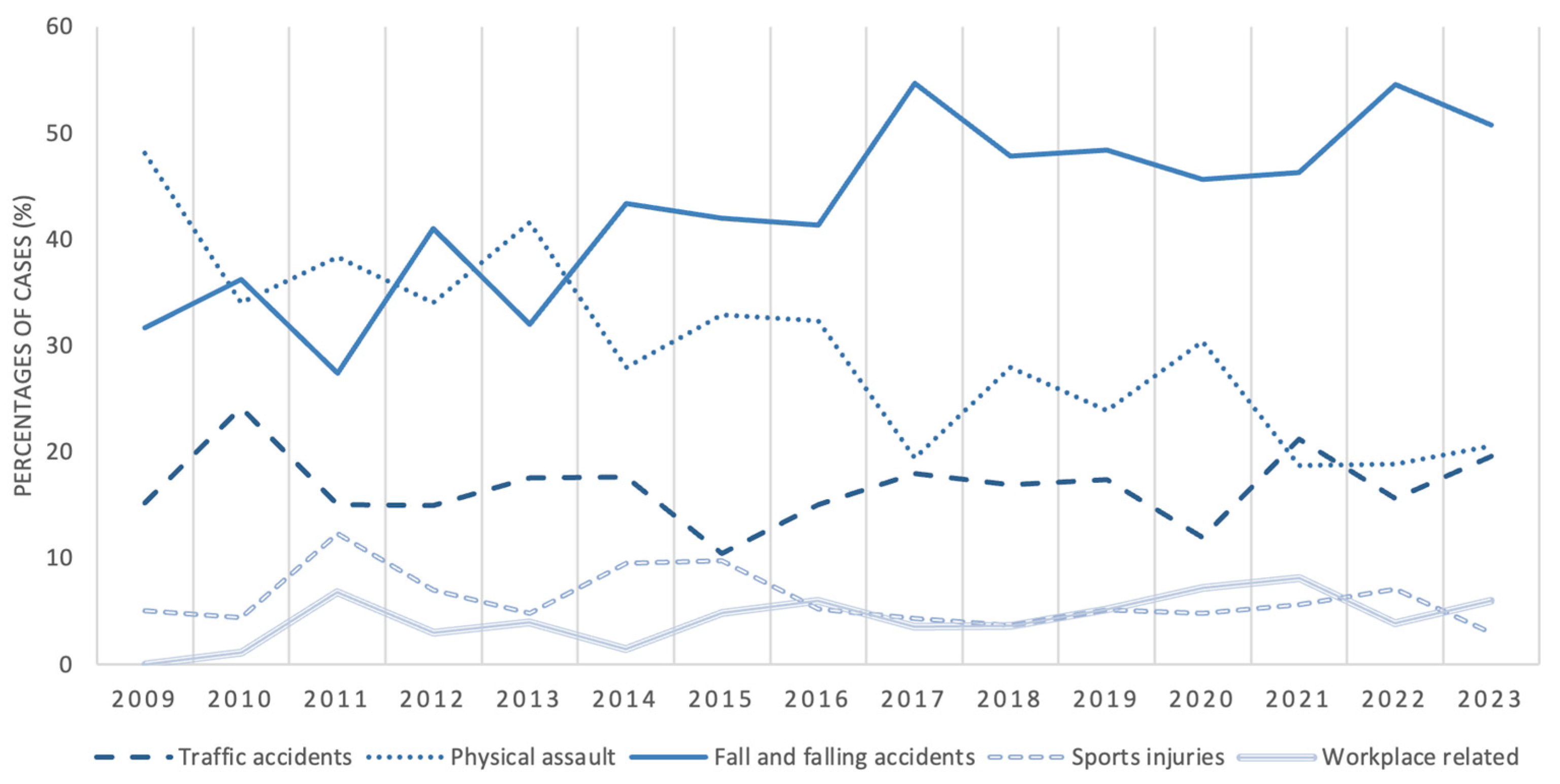

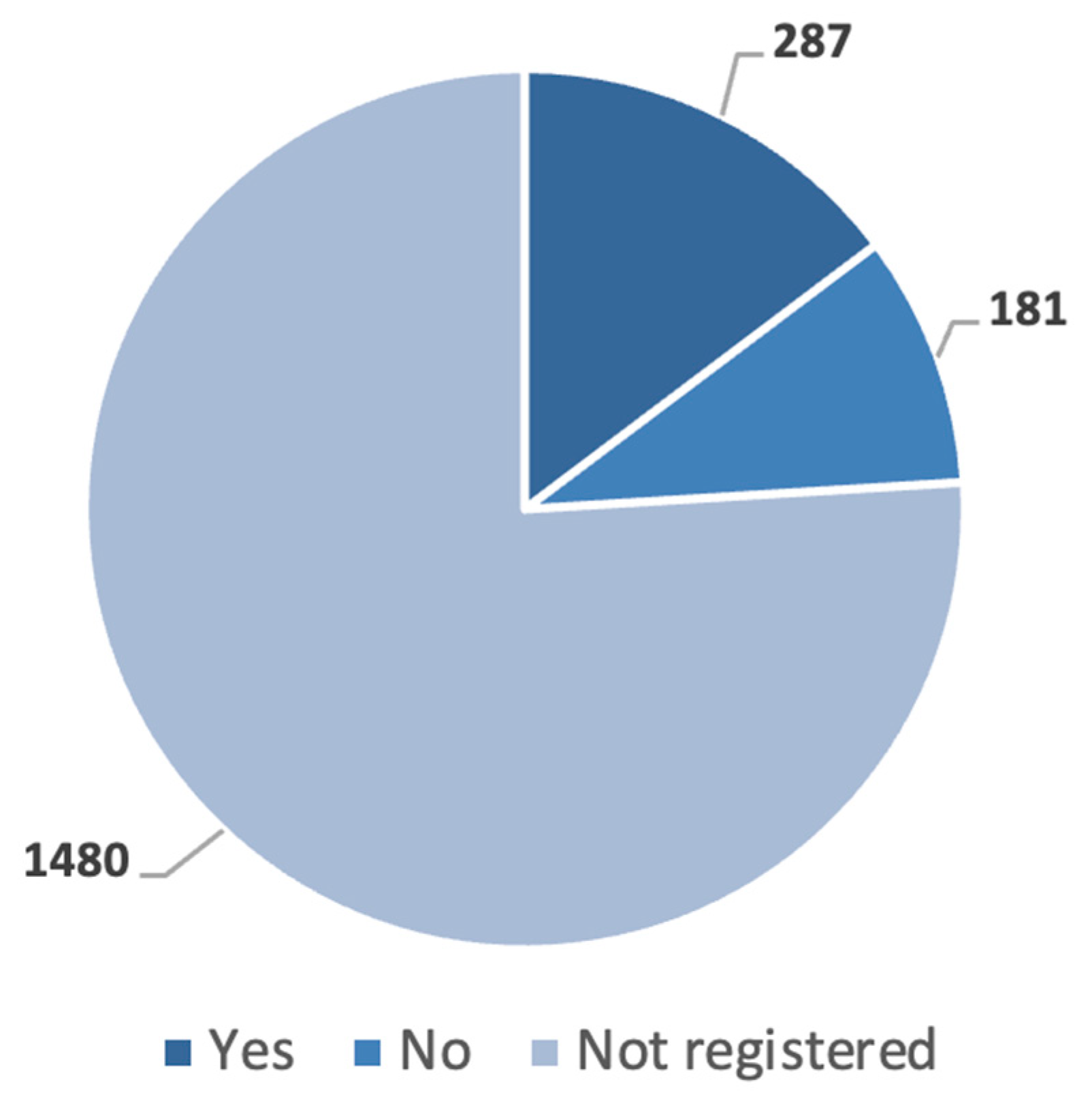

3.3. Distribution by Etiology and Alcohol Consumption

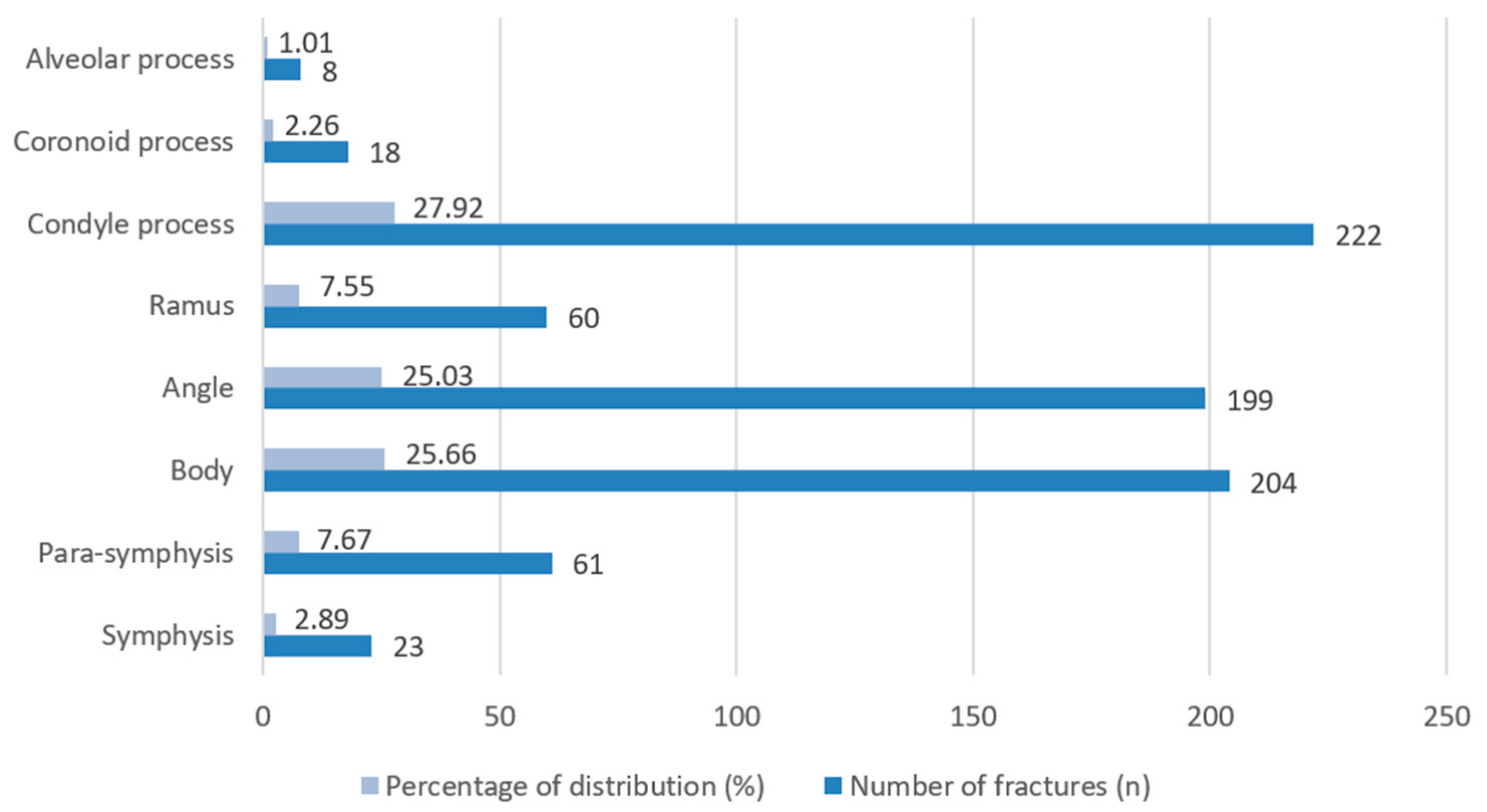

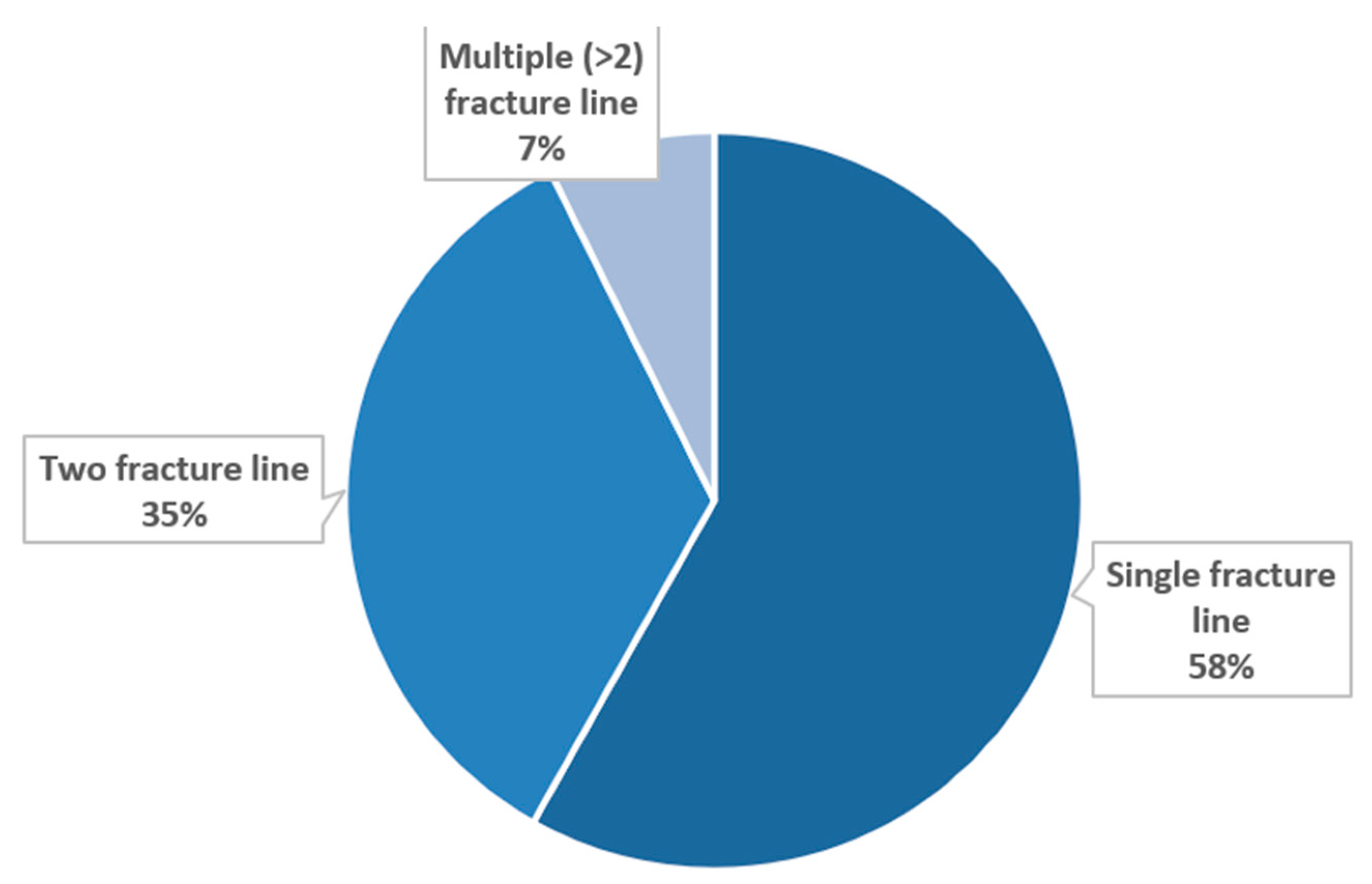

3.4. Characteristics of Mandibular Fractures

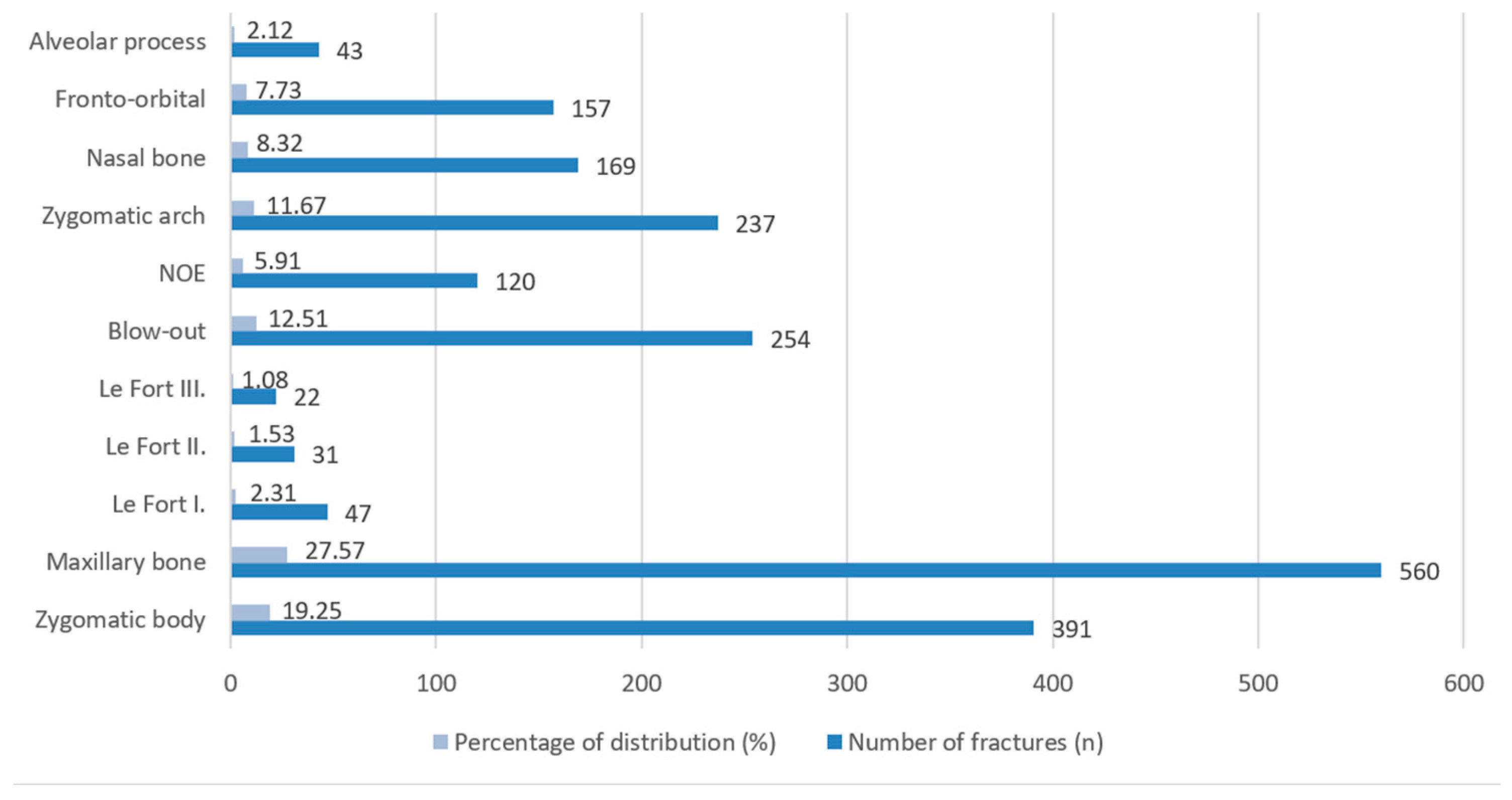

3.5. Characteristics of Maxillofacial Fractures

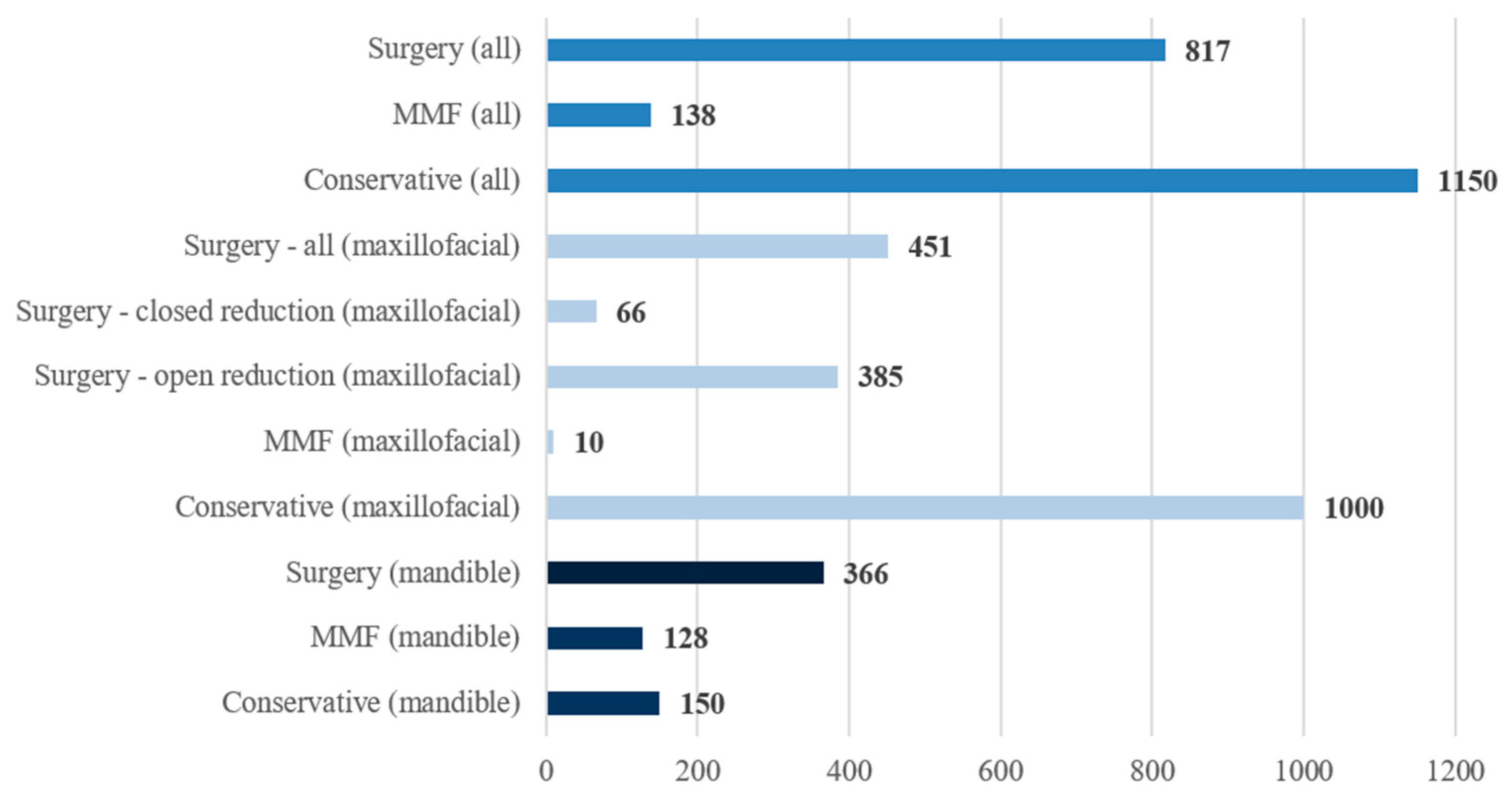

3.6. Characteristics of Therapy for Mandibular and Maxillofacial Fractures

3.7. Distribution of Surgical Fixation Plate Removal by Number and Cause and Postoperative Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ORIF | Open reduction and internal fixation |

| MMF | Mandibulomaxillary fixation |

| KK | Klinikai Központ (Clinical Center) |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| Portable Document Format | |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| USA | United States of America |

| BNO | Betegségek Nemzetközi Osztályozása (Hungarian version of ICD) |

| NOE | Naso-orbito-ethmoidal |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| HCSO | Hungarian Central Statistical Office |

References

- Boffano, P.; Kommers, S.C.; Karagozoglu, K.H.; Forouzanfar, T. Aetiology of maxillofacial fractures: A review of published studies during the last 30 years. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 52, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffano, P.; Roccia, F.; Zavattero, E.; Dediol, E.; Uglešić, V.; Kovačič, Ž.; Vesnaver, A.; Konstantinović, V.S.; Petrović, M.; Stephens, J.; et al. European Maxillofacial Trauma (EURMAT) project: A multicentre and prospective study. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Augustovski, F.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Briggs, A.H.; Carswell, C.; Caulley, L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Greenberg, D.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: Updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, P.A.; Schliephake, H.; Ghali, G.E.; Cascarini, L. Etiology and changing patterns of maxillofacial trauma. In Maxillofacial Surgery, 3rd ed.; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, C.; Manchella, S.; Nastri, A.; Bordbar, P. Mandibular fractures—What a difference 30 years has made. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 60, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallis, G.; Stathopoulos, P.; Igoumenakis, D.; Krasadakis, C.; Mourouzis, C.; Mezitis, M. Treating maxillofacial trauma for over half a century: How can we interpret the changing patterns in etiology and management? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 119, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.J.; Morlandt, A.B. Advancements in Maxillofacial Trauma: A Historical Perspective. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 2256–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, M.; Scivoletto, G.; Pisapia, F.; Priore, P.; Valentini, V. Analysis of Surgical Complications in Mandibular Fractures in the Center of Italy: A Retrospective Study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2024, 35, e71–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmuş, H.İ.; Polat, M.E. A Retrospective Study of the Presentation, Imaging Findings, and Outcomes in 195 Patients with Maxillofacial Fractures Treated with Closed Reduction or Open Reduction with Internal Fixation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e949933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyikwa, C.L.; Okoroafor, F.C.; Onyebuchi, E.P.; Olaopa, O.; Chukwuneke, F.N.; Arakeri, G.; Brennan, P.A. Surgical approaches and postoperative outcomes in zygomatic fractures: A systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 63, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, C.A.; Morris, J.M.; Sharaf, B.A. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma: The Past, Present and the Future. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2023, 34, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccia, F.; Sotong, J.; Savoini, M.; Ramieri, G.; Zavattero, E. Maxillofacial Injuries Due to Traffic Accidents. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, e288–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, I.; Roccia, F.; Aladelusi, T.; Rae, E.; Laverick, S.; Ganasouli, D.; Zanakis, S.N.; de Oliveira Gorla, L.F.; Pereira-Filho, V.A.; Gallafassi, D.; et al. A Multicentric Prospective Study on Maxillofacial Trauma Due to Road Traffic Accidents: The World Oral and Maxillofacial Trauma Project. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2022, 33, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifuentes-Cervantes, J.S.; Bravo-Liranza, V.M.; Pérez-Nuñez, L.I.; Martinez-Rovira, A.; Castro-Núñez, J.; Guerrero, L.M. Facial Injuries in the National Basketball Association. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 81, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, M.; Ali, I.M.; Bayram, A.; Korkmaz, U.T.K.; Sahin, M.; Irmak, S. Challenges in the Head and Neck Department in the Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment of Patients Presenting to a Single Tertiary Hospital of Somalia with Extreme War Injuries. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2023, 34, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonavolontà, P.; Dell’aversana Orabona, G.; Abbate, V.; Vaira, L.A.; Lo Faro, C.; Petrocelli, M.; Attanasi, F.; De Riu, G.; Iaconetta, G.; Califano, L. The epidemiological analysis of maxillofacial fractures in Italy: The experience of a single tertiary center with 1720 patients. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliotta, Y.; Roccia, F.; Sobrero, F.; Ramieri, G.; Volpe, F. Changing trends in maxillofacial injuries among paediatric, adult and elderly populations: A 22-year statistical analysis of 3424 patients in a tertiary care centre in Northwest Italy. Dent. Traumatol. 2024, 40, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spallaccia, F.; Vellone, V.; Colangeli, W.; De Tomaso, S. Maxillofacial Fractures in the Province of Terni (Umbria, Italy) in the Last 11 Years: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2022, 33, e853–e858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Guerrero, E.E.; Guillén-Medina, M.R.; Márquez-Sandoval, F.; Vera-Cruz, J.M.; Gallegos-Arreola, M.P.; Rico-Méndez, M.A.; Aguilar-Velázquez, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Hurtado, I.A. Methodological and Statistical Considerations for Cross-Sectional, Case-Control, and Cohort Studies. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiskes, M.H.; Goeman, J.J.; Beekman, M.; Slagboom, P.E.; Putter, H.; Rodríguez-Girondo, M. Clarifying the biological and statistical assumptions of cross-sectional biological age predictors: An elaborate illustration using synthetic and real data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Çelik, B.; Brouns, S.H.A.; Kaymak, U.; Haak, H.R. No age thresholds in the emergency department: A retrospective cohort study on age differences. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.medcalc.org/calc/odds_ratio.php (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Jaber, M.A.; AlQahtani, F.; Bishawi, K.; Kuriadom, S.T. Patterns of Maxillofacial Injuries in the Middle East and North Africa: A Systematic Review. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, I.; Sobrero, F.; Roccia, F.; Dolan, S.; Laverick, S.; Carlaw, K.; Aquilina, P.; Bojino, A.; Ramieri, G.; Duran-Valles, F.; et al. A multicentric, prospective study on oral and maxillofacial trauma in the female population around the world. Dent. Traumatol. 2022, 38, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicsák, Á.; Koch, L.; Hassfeld, S.; Bonitz, L. A comparison of isolated midface and forehead fractures and pattern of fractures of the midface and forehead in cases with panfacial fractures—A study from 2007 to 2024 on 6588 patients. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2025, 53, 1704–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.Y.; Como, J.J.; Vacca, M.; Nowak, M.J.; Thomas, C.L.; Claridge, J.A. Trends in maxillofacial trauma: A comparison of two cohorts of patients at a single institution 20 years apart. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meisgeier, A.; Pienkohs, S.; Dürrschnabel, F.; Moosdorf, L.; Neff, A. Epidemiologic Trends in Maxillofacial Trauma Surgery in Germany-Insights from the National DRG Database 2005–2022. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Jopp, D.; Ribeiro, O. Centenarians in Europe. Maturitas 2017, 104, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrubka, Z.; Kincses, Á.; Ferenci, T.; Kovács, L.; Gulácsi, L.; Péntek, M. Comparing actuarial and subjective healthy life expectancy estimates: A cross-sectional survey among the general population in Hungary. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.; Kalra, N. A retrospective analysis of maxillofacial injuries in patients reporting to a tertiary care hospital in East Delhi. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2012, 2, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Khanal, N. Is There a Weekend Effect in the Management of Maxillofacial Trauma Patients? J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2022, 19, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, J.E.; Lester, E.L.W.; Maluso, P.J.; Tatebe, L.C.; Bokhari, F. There Is No Weekend Effect in the Trauma Patient. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 258, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, L.D.; da Silveira, I.A.; Nascimento, G.G.; Lund, R.G.; da Silva, R.H.A.; Leite, F.R.M. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Maxillofacial Injuries in Brazil, a 5-year Retrospective Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2018, 17, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, A.B. The incidence and patterns of maxillofacial fractures and associated head and neck injuries. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2024, 52, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruç, M.; Işik, V.M.; Kankaya, Y.; Gürsoy, K.; Sungur, N.; Aslan, G.; Koçer, U. Analysis of Fractured Mandible Over Two Decades. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucoli, M.; Boffano, P.; Romeo, I.; Corio, C.; Benech, A.; Ruslin, M.; Forouzanfar, T.; Starch-Jensen, T.; Rodríguez-Santamarta, T.; de Vicente, J.C.; et al. Management of maxillofacial trauma in the elderly: A European multicenter study. Dent. Traumatol. 2019, 36, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanala, S.; Gudipalli, S.; Perumalla, P.; Jagalanki, K.; Polamarasetty, P.V.; Guntaka, S.; Gudala, A.; Boyapati, R.P. Aetiology, prevalence, fracture site and management of maxillofacial trauma. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2021, 103, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, E.; Makszin, L.; Nyárády, Z.; Olasz, L.; Szalma, J. Age-Related Patterns of Midfacial Fractures in a Hungarian Population: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/iga/en/iga0003.html (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Hoffman, G.R.; Walton, G.M.; Narelda, P.; Qiu, M.M.; Alajami, A. COVID-19 social-distancing measures altered the epidemiology of facial injury: A United Kingdom-Australia comparative study. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, S.G. What is the Impact of the 2020 Coronavirus Lockdown on Maxillofacial Trauma? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1329.e1–1329.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/tur/en/tur0015.html (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Nesset, M.B.; Gudde, C.B.; Mentzoni, G.E.; Palmstierna, T. Intimate partner violence during COVID-19 lockdown in Norway: The increase of police reports. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piquero, A.R.; Jennings, W.G.; Jemison, E.; Kaukinen, C.; Knaul, F.M. Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic—Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 74, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourti, A.; Stavridou, A.; Panagouli, E.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Spiliopoulou, C.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 719–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Olsen, J.; Sun, J.; Chandu, A. Alcohol-involved maxillofacial fractures. Aust. Dent. J. 2017, 62, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikritzhs, T.; Livingston, M. Alcohol and the Risk of Injury. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, J.; Erdogan, M.; Green, R.S. The prevalence of alcohol-related trauma recidivism: A systematic review. Injury 2016, 47, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, R.A.; O’Neill, K.M.; Johnson, D.C.; Becher, R.D.; Schuster, K.M.; Davis, K.A.; Maung, A.A. Assessing the Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Inequities in Blood Alcohol Testing After Trauma. J. Surg. Res. 2022, 273, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualtieri, M.; Pisapia, F.; Fadda, M.T.; Priore, P.; Valentini, V. Mandibular Fractures Epidemiology and Treatment Plans in the Center of Italy: A Retrospective Study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, e346–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancar, B.; Çetiner, Y.; Dayı, E. Evaluation of the pattern of fracture formation from trauma to the human mandible with finite element analysis. Part 2: The corpus and the angle regions. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.; Bebeau, N.P.; Brockhoff, H.; Tandon, R.; Tiwana, P. Mandibular fractures: An analysis of the epidemiology and patterns of injury in 4,143 fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 951.e1–951.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adik, K.; Lamb, P.; Moran, M.; Childs, D.; Francis, A.; Vinyard, C.J. Trends in mandibular fractures in the USA: A 20-year retrospective analysis. Dent. Traumatol. 2023, 39, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamed, A.; Batomen, B.; Boucher, V.; Yadav, K.; Mercier, É.; Isaac, C.J.; Bérubé, M.; Bernard, F.; Chauny, J.M.; Moore, L.; et al. Epidemiology, injury pattern and outcome of older trauma patients: A 15-year study of level-I trauma centers. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, M.M.; Homsi, N.; Pereira, C.C.; Jardim, E.C.; Garcia, I.R., Jr. Epidemiologic evaluation of mandibular fractures in the Rio de Janeiro high-complexity hospital. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2011, 22, 2026–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucoli, M.; Boffano, P.; Broccardo, E.; Benech, A.; Corre, P.; Bertin, H.; Pechalova, P.; Pavlov, N.; Petrov, P.; Tamme, T.; et al. The “European zygomatic fracture” research project: The epidemiological results from a multicenter European collaboration. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.E.; Iezzi, Z.; Licata, J.J.; Othman, S.; Zwillenberg, S. An Update on Maxillary Fractures: A Heterogenous Group. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 1920–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülses, A.; Klingauf, L.; Emmert, M.; Karayürek, F.; Naujokat, H.; Acil, Y.; Wiltfang, J.; Spille, J. Injury patterns and outcomes in bicycle-related maxillofacial traumata: A retrospective analysis of 162 cases. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2022, 50, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojino, A.; Roccia, F.; Carlaw, K.; Aquilina, P.; Rae, E.; Laverick, S.; Romeo, I.; Iocca, O.; Copelli, C.; Sobrero, F.; et al. A multicentric prospective analysis of maxillofacial trauma in the elderly population. Dent. Traumatol. 2022, 38, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, M.K.; Jones, J.P.; Sullivan, M.A.; Amarista, F.J.; Ellis, E., 3rd. Most Facial Fractures Do Not Require Surgical Intervention. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 1628–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Barrachina, R.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; García-Sanz, V.; Almerich-Silla, J.M.; Paredes-Gallardo, V.; Bellot-Arcís, C. Titanium plate removal in orthognathic surgery: Prevalence, causes and risk factors. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widar, F.; Afshari, M.; Rasmusson, L.; Dahlin, C.; Kashani, H. Incidence and risk factors predisposing plate removal following orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2017, 124, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, M.; Gul, M.; Inayat, F.; Ullah, M.J.; Malik, M.; Jehanzeb, N.; Khan, N. Analysis of factors influencing the removal of titanium bone plates in maxillofacial trauma patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Kuroki, T.; Akita, S.; Koizumi, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Rikihisa, N.; Mitsukawa, N.; Satoh, K. Association between plate location and plate removal following facial fracture repair. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2012, 65, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ICD-10 Code (WHO) | BNO Code (Hungarian) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| S02.2 | S0220 | Fracture of nasal bones |

| S02.3 | S0230 | Fracture of orbital floor |

| S02.4 | S0240 | Fracture of malar and maxillary bones |

| S02.6 | S0260 | Fracture of mandible |

| S02.7 | S0270 | Multiple fractures involving skull and facial bones |

| S02.8 | S0280 | Fractures of other skull and facial bones |

| S02.9 | S0290 | Fracture of skull and facial bones, part unspecified |

| Author(s) Year of Publication | Number of Patients (n) | Country | Main Etiological Factors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boffano et al., 2015 [2] | 3396 | Multicenter (Europe) | Physical assaults (39%) Falls and falling accidents (31%) Sport injuries (11%) |

| Bonavolontà et al., 2017 [16] | 1720 | Italy | Traffic accidents (57.1%) Physical assaults (21.7%) Fall and falling accidents (14.2%) |

| Gugliotta et al., 2024 [17] | 3424 | Italy | Physical assaults (27.4%) Traffic accidents (26.2%) Fall and falling accidents (25.2%) |

| Spallaccia et al., 2022 [18] | 603 | Italy | Traffic accidents (36%) Fall and falling accidents (27%) Sport injuries (13%) and physical assaults (13%) |

| Martinez et al., 2014 [26] | 1736 | USA | Physical assaults (29.7%) Traffic accidents (29.6%) Fall and falling accidents (22.1%) |

| Kapoor et al., 2012 [30] | 1000 | India | Physical assaults (53.8%) Traffic accidents (40.4%) Fall and falling accidents (3.3%) |

| Conceição et al., 2018 [33] | 3262 | Brazil | Physical assaults (81.8%) Traffic accidents (11.4%) Fall and falling accidents (4.9%) |

| Bataineh, 2024 [34] | 481 | Jordan | Traffic accidents (62.1%) Physical assaults (15.2%) Fall and falling accidents (15%) |

| Oruç et al., 2016 [35] | 283 | Turkey | Physical assaults (36.7%) Traffic accidents (32.9%) Fall and falling accidents (29.3%) |

| Brucoli et al., 2019 [36] | 1406 | Multicenter (Europe) | Physical assaults (38%) Fall and falling accidents (30%) Traffic accidents (14%) |

| Kanala et al. 2021 [37] | 1112 | India | Traffic accidents (70%) Fall and falling accidents (19%) Physical assaults (9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rajnics, Z.; Horváth, O.; Horváth, V.; Salimian, P.; Marada, G.; Szalma, J. Maxillofacial Fractures in Southern Hungary: A 15-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of 1948 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010280

Rajnics Z, Horváth O, Horváth V, Salimian P, Marada G, Szalma J. Maxillofacial Fractures in Southern Hungary: A 15-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of 1948 Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010280

Chicago/Turabian StyleRajnics, Zsolt, Olivér Horváth, Viktória Horváth, Parnia Salimian, Gyula Marada, and József Szalma. 2026. "Maxillofacial Fractures in Southern Hungary: A 15-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of 1948 Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010280

APA StyleRajnics, Z., Horváth, O., Horváth, V., Salimian, P., Marada, G., & Szalma, J. (2026). Maxillofacial Fractures in Southern Hungary: A 15-Year Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of 1948 Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010280