Evolution of Retinal Morphology Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. OCT Data

3.3. Clinical Scores

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

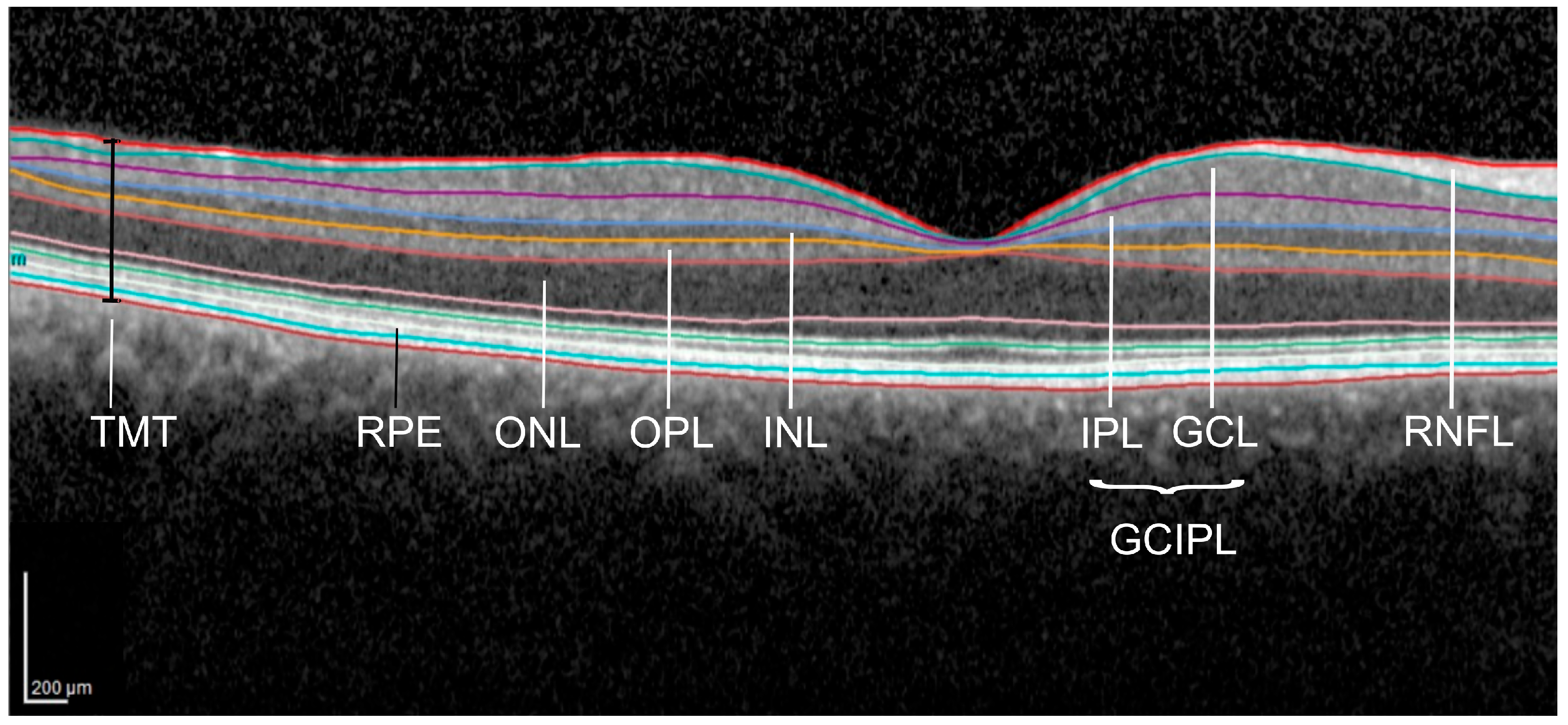

| TMT | total macular thickness |

| pRNFL | peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer |

| mRNFL | macular retinal nerve fiber layer |

| GCIPL | complex of GCL = ganglion cell layer + IPL = inner plexiform layer |

| INL | inner nuclear layer |

| OPL | outer plexiform layer |

| ONL | outer nuclear layer |

| RPE | retinal pigment epithelium |

| ALS | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| OCT | optic coherence tomography |

| HCs | healthy controls |

| ALS-FRS | ALS functional rating scale |

| mRS | modified Rankin scale |

| GEE | generalized estimation equation model |

References

- Goutman, S.A.; Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chió, A.; Savelieff, M.G.; Kiernan, M.C.; Feldman, E.L. Recent advances in the diagnosis and prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura-Kiyono, C.; Kimura, F.; Ishida, S.; Nakajima, H.; Hosokawa, T.; Sugino, M.; Hanafusa, T. Onset and spreading patterns of lower motor neuron involvements predict survival in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2011, 82, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, H.E.; McCluskey, L.; Elman, L.; Hoskins, K.; Talman, L.; Grossman, M.; Balcer, L.J.; Galetta, S.L.; Liu, G.T. Cross-sectional evaluation of clinical neuro-ophthalmic abnormalities in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis population. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 314, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, Y.; Sitty, M. Non-Motor Symptoms of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Multi-Faceted Disorder. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2021, 8, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R. Diagnosing ALS: The Gold Coast criteria and the role of EMG. Pract. Neurol. 2022, 22, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60: II. Prognosis. Scott. Med. J. 1957, 2, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulter, G.; Steen, C.; de Keyser, J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke 1999, 30, 1538–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedarbaum, J.M.; Stambler, N.; Malta, E.; Fuller, C.; Hilt, D.; Thurmond, B.; Nakanishi, A. The ALSFRS-R: A revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 169, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Writing Group. Safety and efficacy of edaravone in well defined patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; Itoyama, Y.; Sobue, G.; Tsuji, S.; Aoki, M.; Doyu, M.; Hamada, C.; Kondo, K.; Yoneoka, T.; Akimoto, M.; et al. Confirmatory double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety of edaravone (MCI-186) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2014, 15, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchi, E.; Vinceti, M.; Malagoli, C.; Fini, N.; Gessani, A.; Fasano, A.; Rizzi, R.; Sette, E.; Cavazza, S.; Fiocchi, A.; et al. High-frequency motor rehabilitation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomized clinical trial. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019, 6, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Montuschi, A.; Pender, N.; Chio, A.; Hardiman, O. Predicting prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A simple algorithm. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Janse Mantgem, M.R.; van Eijk, R.P.A.; van der Burgh, H.K.; Tan, H.H.G.; Westeneng, H.J.; van Es, M.A.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Prognostic value of weight loss in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidha, S.; Syc, S.B.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Eckstein, C.; Warner, C.V.; Farrell, S.K.; Oakley, J.D.; Durbin, M.K.; Meyer, S.A.; Balcer, L.J.; et al. Primary retinal pathology in multiple sclerosis as detected by optical coherence tomography. Brain A J. Neurol. 2011, 134, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesler, A.; Vakhapova, V.; Korczyn, A.D.; Naftaliev, E.; Neudorfer, M. Retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2011, 113, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, P.; Müller, A.-K.; Südmeyer, M.; Ferrea, S.; Ringelstein, M.; Cohn, E.; Aktas, O.; Dietlein, T.; Lappas, A.; Foerster, A.; et al. Optical coherence tomography in parkinsonian syndromes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringelstein, M.; Albrecht, P.; Südmeyer, M.; Harmel, J.; Müller, A.; Keser, N.; Finis, D.; Ferrea, S.; Guthoff, R.; Schnitzler, A.; et al. Subtle retinal pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2014, 1, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytulun, A.; Cruz-Herranz, A.; Aktas, O.; Balcer, L.J.; Balk, L.; Barboni, P.; Blanco, A.A.; Calabresi, P.A.; Costello, F.; Sanchez-Dalmau, B.; et al. APOSTEL 2.0 Recommendations for Reporting Quantitative Optical Coherence Tomography Studies. Neurology 2021, 97, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Herranz, A.; Balk, L.J.; Oberwahrenbrock, T.; Saidha, S.; Martinez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Lagreze, W.A.; Schuman, J.S.; Villoslada, P.; Calabresi, P.; Balcer, L.; et al. The APOSTEL recommendations for reporting quantitative optical coherence tomography studies. Neurology 2016, 86, 2303–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewarie, P.; Balk, L.; Costello, F.; Green, A.; Martin, R.; Schippling, S.; Petzold, A. The OSCAR-IB consensus criteria for retinal OCT quality assessment. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, N.M.; Saidha, S.; Zimmermann, H.; Brandt, A.U.; Oberwahrenbrock, T.; Maragakis, N.J.; Tumani, H.; Ludolph, A.C.; Meyer, T.; Calabresi, P.A.; et al. Optical coherence tomography does not support optic nerve involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2013, 20, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.; de Hoz, R.; Ramírez, A.I.; Ferreras, A.; Salobrar-Garcia, E.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.L.; Urcelay-Segura, J.L.; Salazar, J.J.; Ramírez, J.M. Changes in Retinal OCT and Their Correlations with Neurological Disability in Early ALS Patients, a Follow-Up Study. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohani, M.; Meysamie, A.; Zamani, B.; Sowlat, M.M.; Akhoundi, F.H. Reduced retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness in ALS patients: A window to disease progression. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, G.; Kharel, S.; Coghlan, M.A.; Yadav, J.K.; Parajuli, P.; Pandit, K.; Shing, Y.K.; Ojha, R. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and retinal changes in optical coherence tomography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, N.J.; Simonett, J.; Fawzi, A.A.; Siddique, T. Ophthalmic Manifestations of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (An American Ophthalmological Society Thesis). Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 2015, 113, T12. [Google Scholar]

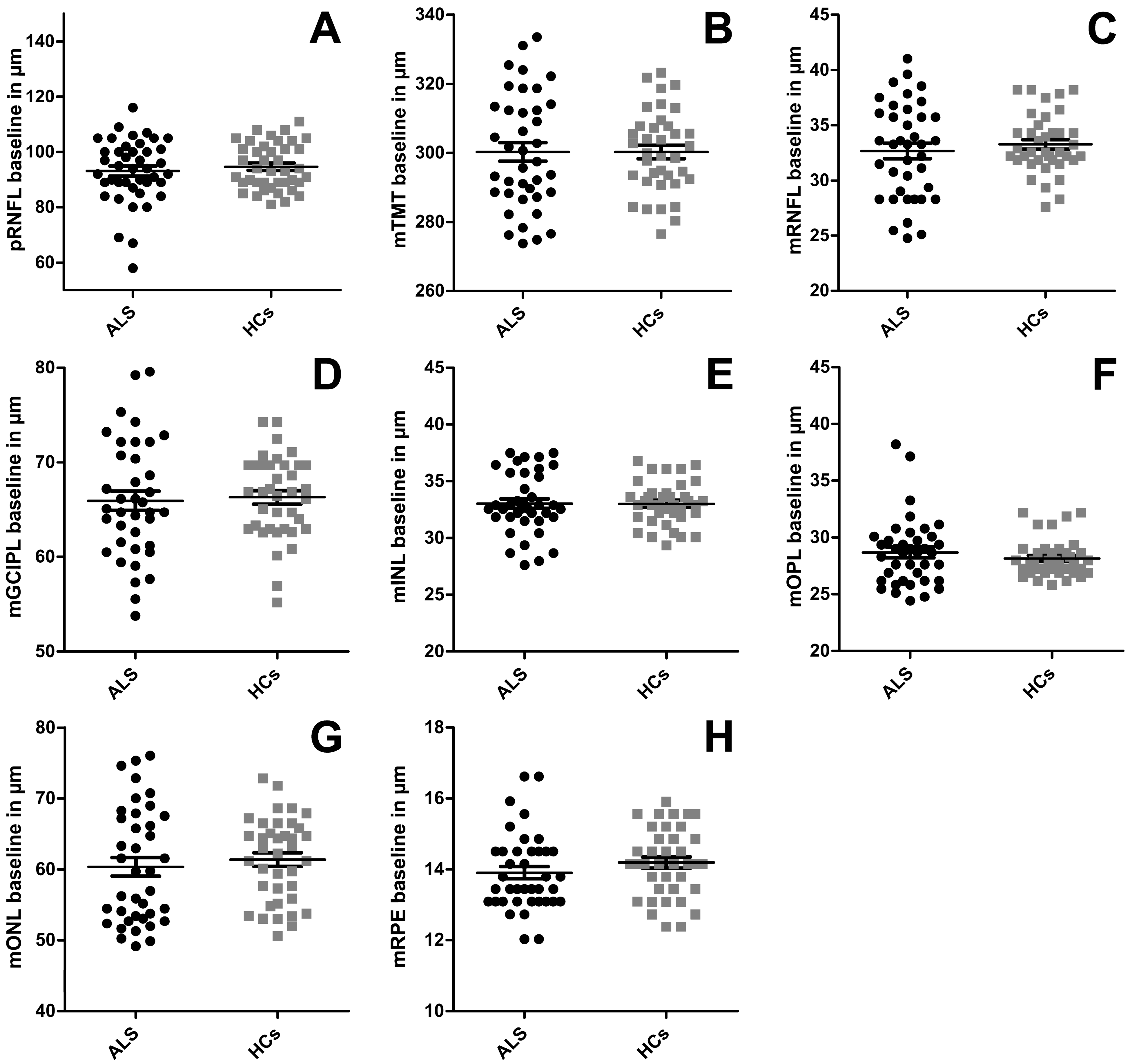

| OCT Layer, µm a | ALS | HCs | Statistics: ALS vs. HC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline a | (n = 22) | (n = 21) | GEE |

| pRNFL | 93.20 (±1.83) | 94.15 (±1.38) | p = 0.357 |

| TMT | 299.63 (±2.74) | 300.18 (±2.01) | p = 0.711 |

| mRNFL | 32.44 (±0.67) | 33.26 (±0.46) | p = 0.383 |

| mGCIPL | 65.74 (±1.02) | 66.12 (±0.73) | p = 0.525 |

| mINL | 33.03 (±0.44) | 32.87 (±0.31) | p = 0.773 |

| mOPL | 28.58 (±0.48) | 28.19 (±0.28) | p = 0.399 |

| mONL | 60.46 (±1.33) | 61.20 (±1.00) | p = 0.631 |

| mRPE | 13.90 (±0.18) | 14.14 (±0.916) | p = 0.367 |

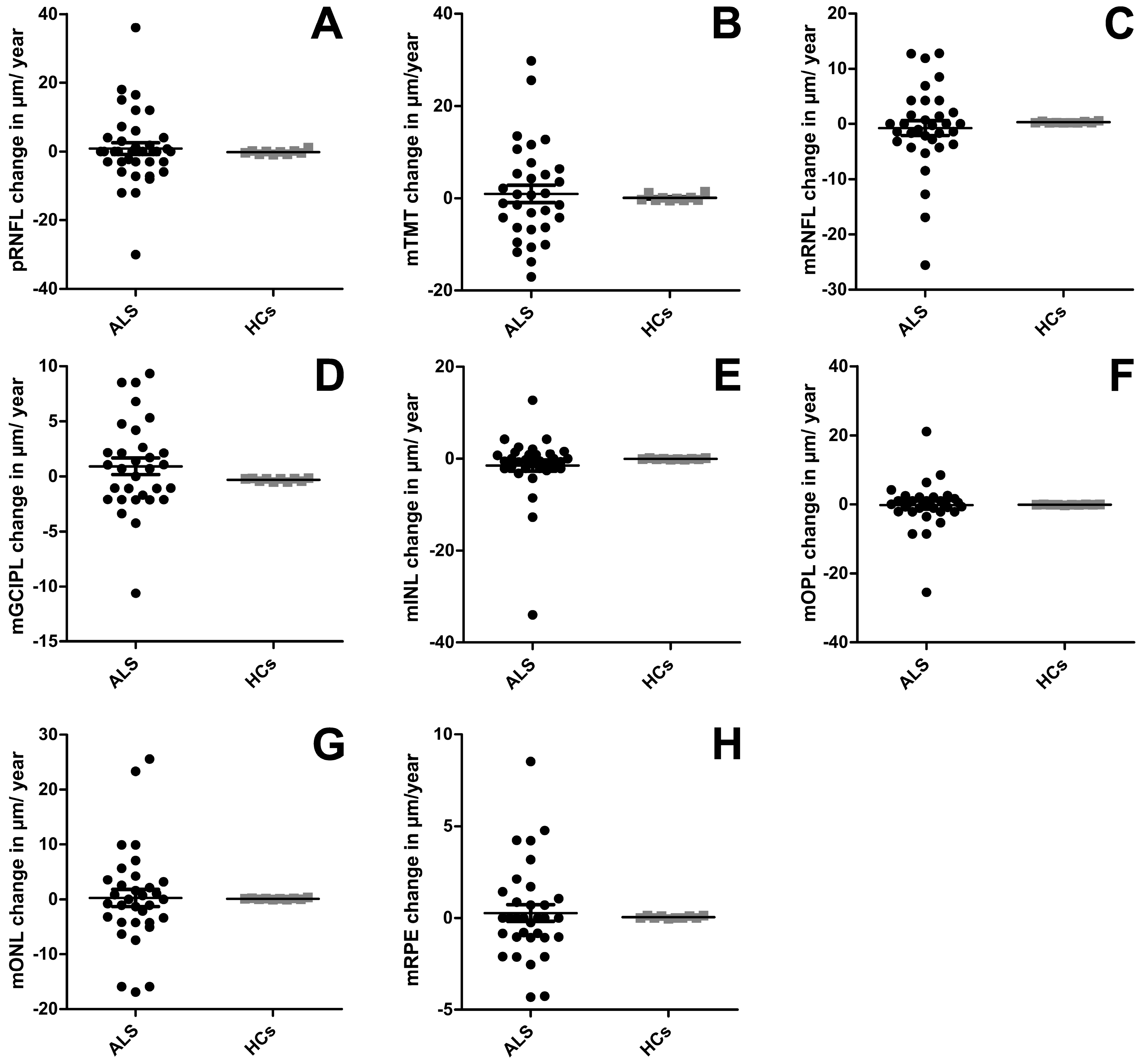

| Annualized Change Rate After 12 Months b,c | |||

| (n = 22) | (n = 5) | Mann–Whitney d | |

| pRNFL | −1.73 (±2.50); p = 0.928 b (<0.001 c) | −0.18 (±1.93); p = 0.005 c | p = 0.864 |

| TMT | 0.94 (±1.85); p = 0.080 (<0.001) | 0.70 (±0.22); p = 0.005 | p = 0.703 |

| mRNFL | 0.00 (±1.14); p = 0.071 (<0.001) | 0.30 (±0.05); p = 0.005 | p = 0.182 |

| mGCIPL | 0.91 (±0.75); p = 0.402 (<0.001) | −0.31 (±0.05); p = 0.005 | p = 0.340 |

| mINL | −0.48 (±0.71); p = 0.654 (<0.001) | −0.06 (±0.04); p = 0.005 | p = 0.849 |

| mOPL | 0.56 (±0.90); p = 0.274 (<0.001) | −0.12 (±0.02); p = 0.005 | p = 0.341 |

| mONL | 0.78 (±1.50); p = 0.867 (<0.001) | −0.09 (±0.04); p = 0.005 | p = 0.849 |

| mRPE | 0.15 (±0.45); p = 0.381 (<0.001) | −0.04 (±0.02); p = 0.005 | p = 0.503 |

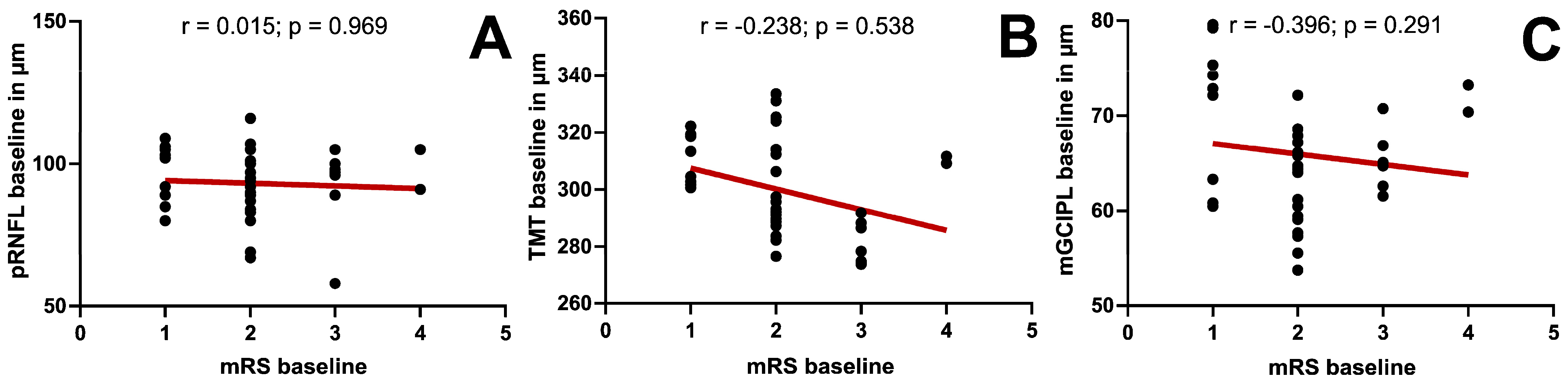

| OCT-Parameter, µm | mRS (n = 22) | BI (n = 9) | ALSFRS-R (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| pRNFL | 0.15 (p = 0.969) | 0.25 (p = 0.517) | −0.348 (p = 0.499) |

| TMT | −0.238 (p = 0.538) | −0.079 (p = 0.839) | −0.086 (p = 0.872) |

| mRNFL | −0.337 (p = 0.376) | 0.129 (p = 0.741) | 0.600 (p = 0.208) |

| mGCIPL | −0.396 (p = 0.291) | 0.099 (p = 0.800) | −0.257 (p = 0.623) |

| mINL | −0.487 (p = 0.183) | 0.03 (p = 0.939) | −0.464 (p = 0.354) |

| mOPL | −0.644 (p = 0.061) | 0.119 (p = 0.761) | −0.314 (p = 0.544) |

| mONL | 0.218 (p = 0.573) | −0.099 (p = 0.800) | −0.257 (p = 0.623) |

| mRPE | −0.219 (p = 0.572) | 0.592 (p = 0.093) | 0.314 (p = 0.544) |

| Follow-Up | |||

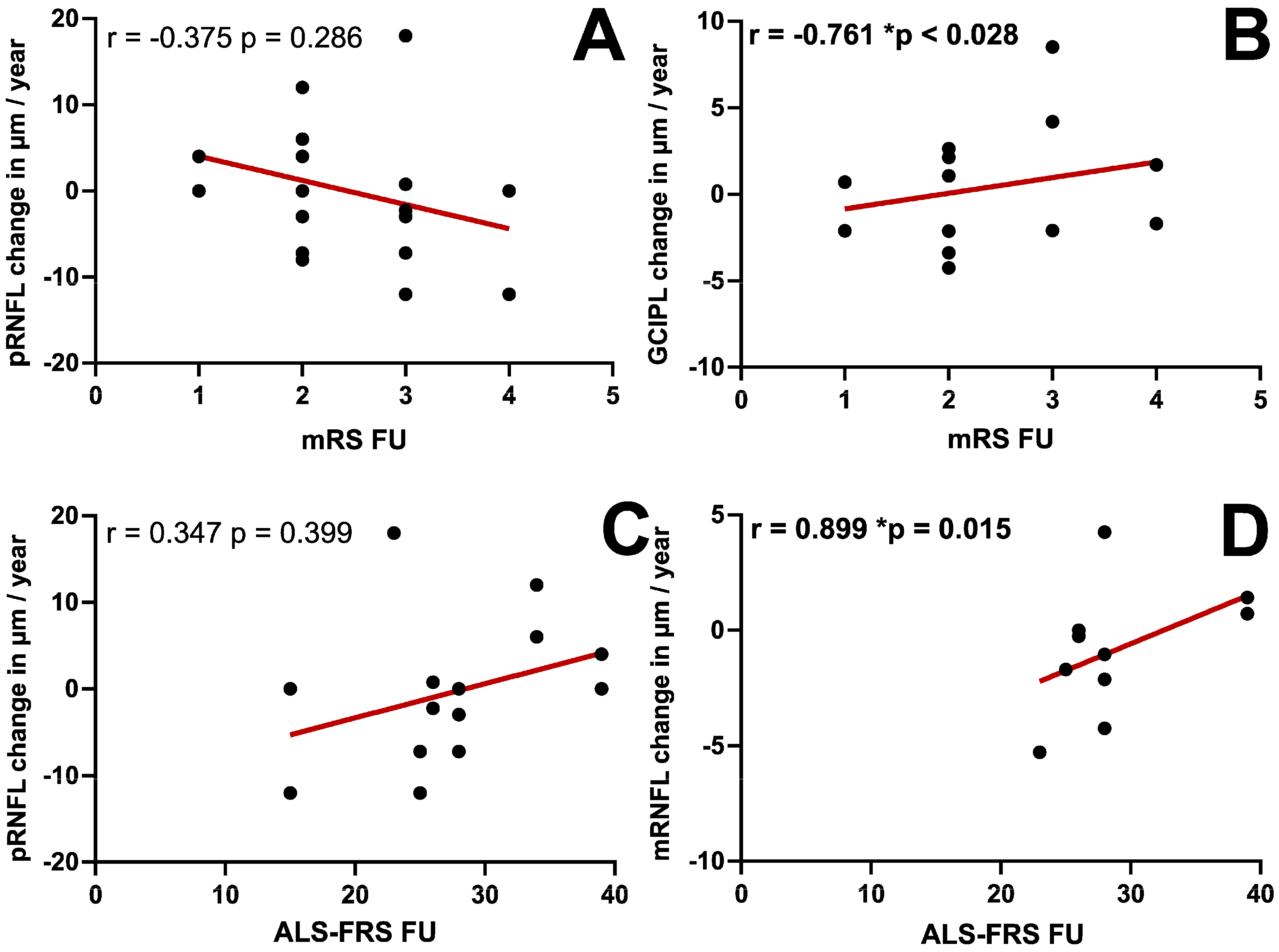

| pRNFL | −0.375 (p = 0.286) | 0.006 (p = 0.986) | 0.347 (p = 0.399) |

| TMT | −0.391 (p = 0.338) | 0.064 (p = 0.881) | 0.406 (p = 0.425) |

| mRNFL | −0.587 (p = 0.126) | 0.37 (p = 0.366) | 0.899 (p = 0.015) |

| mGCIPL | −0.761 (p = 0.028) | 0.54 (p = 0.168) | 0.754 (p = 0.084) |

| mINL | −0.531 (p = 0.175) | 0.373 (p = 0.363) | 0.638 (p = 0.173) |

| mOPL | 0.548 (p = 0.160) | −0.026 (p = 0.952) | −0.232 (p = 0.658) |

| mONL | −0.587 (p = 0.126) | −0.128 (p = 0.763) | 0.174 (p = 0.742) |

| mRPE | 0.156 (p = 0.711) | −0.549 (p = 0.159) | −0.464 (p = 0.354) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Koska, V.; Teufel, S.; Aytulun, A.; Weise, M.; Ringelstein, M.; Guthoff, R.; Meuth, S.G.; Albrecht, P. Evolution of Retinal Morphology Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010258

Koska V, Teufel S, Aytulun A, Weise M, Ringelstein M, Guthoff R, Meuth SG, Albrecht P. Evolution of Retinal Morphology Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010258

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoska, Valeria, Stefanie Teufel, Aykut Aytulun, Margit Weise, Marius Ringelstein, Rainer Guthoff, Sven G. Meuth, and Philipp Albrecht. 2026. "Evolution of Retinal Morphology Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010258

APA StyleKoska, V., Teufel, S., Aytulun, A., Weise, M., Ringelstein, M., Guthoff, R., Meuth, S. G., & Albrecht, P. (2026). Evolution of Retinal Morphology Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010258