Clinical Outcomes of Surgery Versus Radiotherapy in Bilsky Grade 3 Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

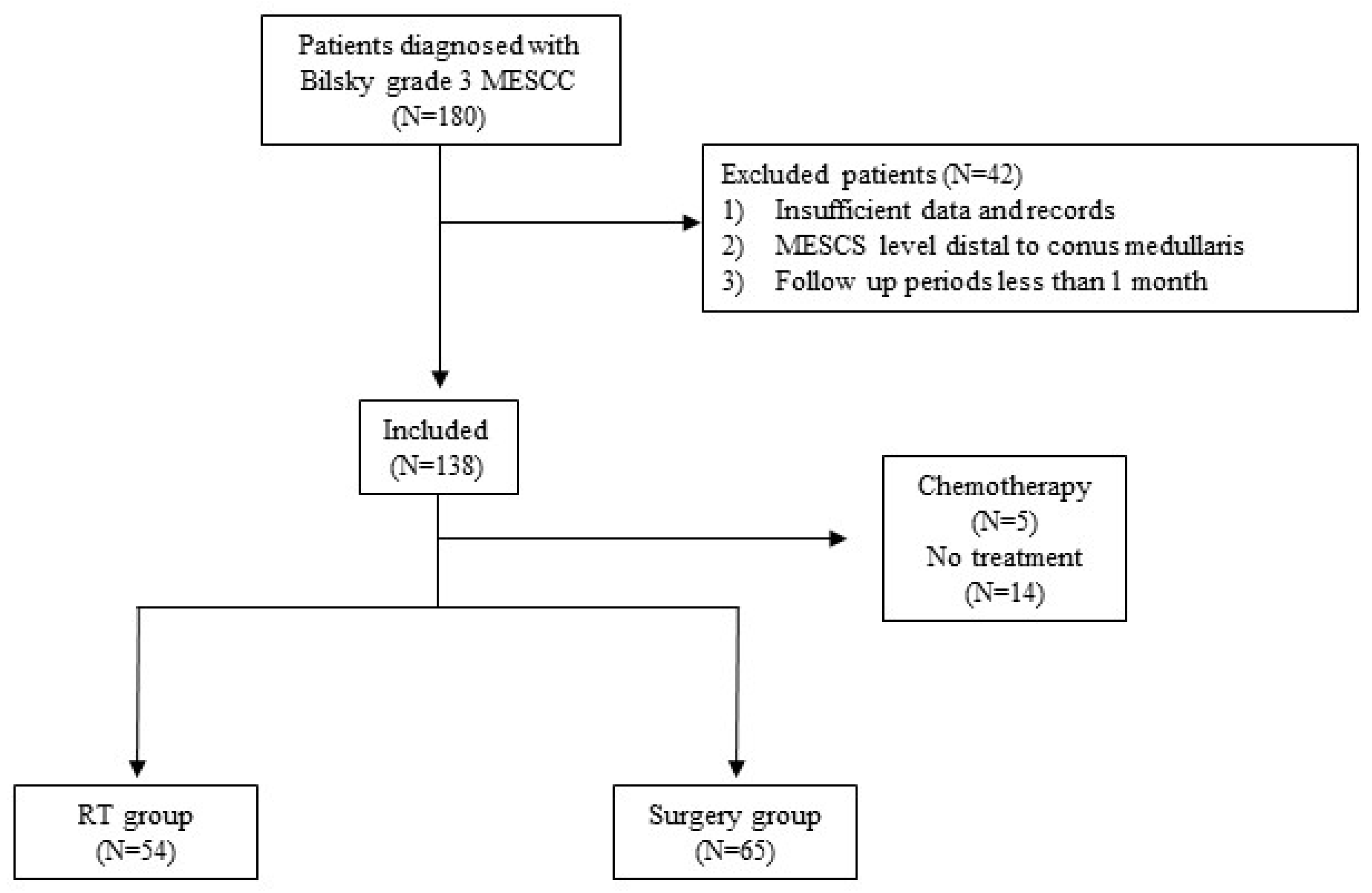

2.1. Study Design and Patient Inclusion

2.2. Data Collection and Outcome Evaluation

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

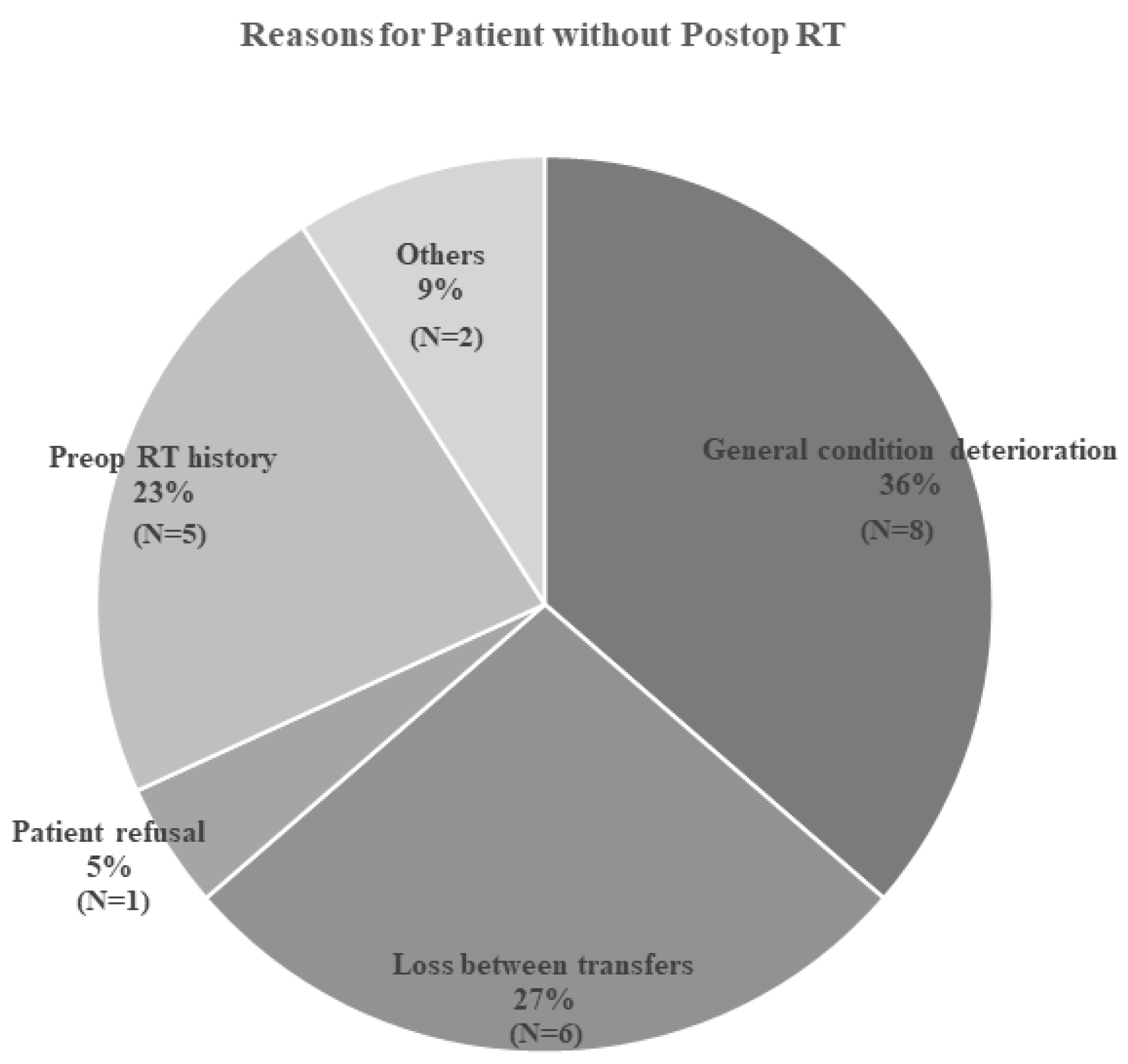

3.1. Comparison Between the RT and Surgery Groups

3.2. Risk Factor Analysis for Local Progression, Motor Recovery, and Ambulatory Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MESCC | Metastatic epidural spinal cord compression |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SBRT | Stereotactic body radiation therapy |

| EBRT | External beam radiation therapy |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status |

| SINS | Spine Instability Neoplastic Score |

| mMRC | Modified Medical Research Council |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| IRB | Institutional review board |

References

- Van den Brande, R.; Cornips, E.M.; Peeters, M.; Ost, P.; Billiet, C.; Van de Kelft, E. Epidemiology of spinal metastases, metastatic epidural spinal cord compression and pathologic vertebral compression fractures in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 35, 100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.X.; Gong, Y.N.; Jiang, X.D.; Jiang, L.; Zhuang, H.Q.; Meng, N.; Liu, X.G.; Wei, F.; Liu, Z.J. Local Tumor Control for Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression Following Separation Surgery with Adjuvant CyberKnife Stereotactic Radiotherapy or Image-Guided Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy. World Neurosurg. 2020, 141, e76–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, D.H.; Hwang, C.J.; Cho, J.H. Spine surgery for metastatic spine cancer in the era of advanced radiation therapy. Asian Spine J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavourakis, M.; Sakellariou, E.; Galanis, A.; Karampinas, P.; Zachariou, D.; Tsalimas, G.; Marougklianis, V.; Argyropoulou, E.; Rozis, M.; Kaspiris, A.; et al. Comprehensive Insights into Metastasis-Associated Spinal Cord Compression: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis: A State-of-the-Art Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, I.; Rubin, D.G.; Lis, E.; Cox, B.W.; Stubblefield, M.D.; Yamada, Y.; Bilsky, M.H. The NOMS Framework: Approach to the Treatment of Spinal Metastatic Tumors. Oncology 2013, 18, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Perna, G.; Baldassarre, B.; Armocida, D.; De Marco, R.; Pesaresi, A.; Badellino, S.; Bozzaro, M.; Petrone, S.; Buffoni, L.; Sonetto, C.; et al. Application of the NSE score (Neurology-Stability-Epidural compression assessment) to establish the need for surgery in spinal metastases of elderly patients: A multicenter investigation. Eur. Spine J. 2024, 33, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Lee, D.H.; Hwang, C.J.; Jeong, G.; Choi, J.U.; Sohn, H.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Cho, J.H. Treatment Approach for Bilsky Grade 2 Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression Based on Radiation Therapy Failure Risk. Glob. Spine J. 2025, 21925682251359292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, J.W.; Park, J.H.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, D.H.; Hwang, C.J.; Yang, J.J.; Cho, J.H. Factors affecting the prognosis of recovery of motor power and ambulatory function after surgery for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Neurosurg. Focus 2022, 53, E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, I.; Zuckerman, S.L.; Bird, J.E.; Bilsky, M.H.; Lazáry, Á.; Quraishi, N.A.; Fehlings, M.G.; Sciubba, D.M.; Shin, J.H.; Mesfin, A.; et al. Predicting Neurologic Recovery after Surgery in Patients with Deficits Secondary to MESCC: Systematic Review. Spine 2016, 41, S224–S230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, Q.; Ke, L.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L. The impact of radiosensitivity on clinical outcomes of spinal metastases treated with stereotactic body radiotherapy. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 13279–13289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendfeldt, G.A.; Chanbour, H.; Chen, J.W.; Gangavarapu, L.S.; LaBarge, M.E.; Ahmed, M.; Jonzzon, S.; Roth, S.G.; Chotai, S.; Luo, L.Y.; et al. Does Low-Grade Versus High-Grade Bilsky Score Influence Local Recurrence and Overall Survival in Metastatic Spine Tumor Surgery? Neurosurgery 2023, 93, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uei, H.; Tokuhashi, Y.; Maseda, M. Analysis of the Relationship Between the Epidural Spinal Cord Compression (ESCC) Scale and Paralysis Caused by Metastatic Spine Tumors. Spine 2018, 43, E448–E455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murotani, K.; Fujibayashi, S.; Otsuki, B.; Shimizu, T.; Sono, T.; Onishi, E.; Kimura, H.; Tamaki, Y.; Tsubouchi, N.; Ota, M.; et al. Prognostic Factors after Surgical Treatment for Spinal Metastases. Asian Spine J. 2024, 18, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dea, N.; Versteeg, A.L.; Sahgal, A.; Verlaan, J.J.; Charest-Morin, R.; Rhines, L.D.; Sciubba, D.M.; Schuster, J.M.; Weber, M.H.; Lazary, A.; et al. Metastatic Spine Disease: Should Patients with Short Life Expectancy Be Denied Surgical Care? An International Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurosurgery 2020, 87, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leshem, Y.; Dolev, Y.; Siegelmann-Danieli, N.; Sharman Moser, S.; Apter, L.; Chodick, G.; Nikolaevski-Berlin, A.; Shamai, S.; Merimsky, O.; Wolf, I. Association between diabetes mellitus and reduced efficacy of pembrolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 2789–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Zhang, S.; Ou, F.S.; Venook, A.P.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Lenz, H.J.; Innocenti, F.; O’Neil, B.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Polite, B.N.; et al. Diabetes and Clinical Outcome in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: CALGB 80405 (Alliance). JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2020, 4, pkz078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues Mantuano, N.; Stanczak, M.A.; Oliveira, I.A.; Kirchhammer, N.; Filardy, A.A.; Monaco, G.; Santos, R.C.; Fonseca, A.C.; Fontes, M.; Bastos, C.S., Jr.; et al. Hyperglycemia Enhances Cancer Immune Evasion by Inducing Alternative Macrophage Polarization through Increased O-GlcNAcylation. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildegaard, T.H.; Sabroe, D.; Wang, M.; Høy, K. How to select a treatment method for patients with potentially unstable metastatic vertebrae (spinal instability neoplastic score 7–12): A systematic review. Asian Spine J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, N.; Faddoul, J.; Tarabay, B.; Attieh, C.; Chalah, M.A.; Ayache, S.S.; Abi Lahoud, G.N. Ten Years After SINS: Role of Surgery and Radiotherapy in the Management of Patients with Vertebral Metastases. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 802595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.C.Y.; Lee, S.F.; Chan, A.W.; Caini, S.; Hoskin, P.; Simone, C.B., 2nd; Johnstone, P.; van der Linden, Y.; van der Velden, J.M.; Martin, E.; et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus conventional external beam radiotherapy for spinal metastases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 189, 109914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Deshmukh, S.; Timmerman, R.D.; Movsas, B.; Gerszten, P.; Yin, F.-F.; Dicker, A.; Abraham, C.D.; Zhong, J.; Shiao, S.L.; et al. Stereotactic Radiosurgery vs Conventional Radiotherapy for Localized Vertebral Metastases of the Spine: Phase 3 Results of NRG Oncology/RTOG 0631 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.; Chang, B.S.; Kim, H.; Hong, S.H.; Chang, S.Y. Separation surgery followed by stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for metastatic epidural spinal cord compression: A systematic review and meta-analysis for local progression rate. J. Bone Oncol. 2022, 36, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patchell, R.A.; Tibbs, P.A.; Regine, W.F.; Payne, R.; Saris, S.; Kryscio, R.J.; Mohiuddin, M.; Young, B. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: A randomised trial. Lancet 2005, 366, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quraishi, N.A.; Arealis, G.; Salem, K.M.; Purushothamdas, S.; Edwards, K.L.; Boszczyk, B.M. The surgical management of metastatic spinal tumors based on an Epidural Spinal Cord Compression (ESCC) scale. Spine J. 2015, 15, 1738–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber-Levine, C.; Jiang, K.; Al-Mistarehi, A.-H.; Welland, J.; Hersh, A.M.; Horowitz, M.A.; Davidar, A.D.; Sattari, S.A.; Redmond, K.J.; Lee, S.H.; et al. The role of combination surgery and radiotherapy in patients with metastatic spinal cord compression: What are the remaining grey areas? A systematic review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2025, 248, 108632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| RT Group (N = 54) | Surgery Group (N = 65) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient demographics | |||

| Age | 61.62 (±11.86) | 58.12 (±12.41) | 0.124 |

| Sex (M:F) | 34:20 | 48:17 | 0.235 |

| DM | 8 | 12 | 0.615 |

| HTN | 20 | 13 | 0.208 |

| Smoking | 22 | 27 | 1.000 |

| Pathology | 0.301 | ||

| Lung | 17 | 16 | |

| HCC | 10 | 12 | |

| RCC | 2 | 5 | |

| Breast cancer | 2 | 3 | |

| GI | 6 | 10 | |

| Hematologic | 4 | 4 | |

| GU | 9 | 3 | |

| OBGY | 2 | 4 | |

| Sarcoma | 2 | 3 | |

| Others | 0 | 5 | |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| ECOG | 2.10 ± 1.22 | 2.12 ± 1.09 | 0.895 |

| Initial symptoms | 0.003 * | ||

| No symptom | 2 | 0 | |

| Pain | 23 | 14 | |

| Weakness | 29 | 51 | |

| Motor grade for patients with weakness | 3.54 ± 1.72 | 2.90 ± 1.54 | 0.042 * |

| Image findings | |||

| Involved location (Cervical:Thoracic:Multiple) | 6:45:3 | 8:56:1 | 0.499 |

| Pathologic fracture | 24 | 42 | 0.063 |

| Compression direction (Anterior:Posterior:Circumferential) | 5:6:43 | 10:7:48 | 0.673 |

| SINS | 10.27 ± 3.23 | 11.08 ± 2.84 | 0.16 |

| RT Group (N = 54) | Surgery Group (N = 65) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor recovery | <0.001 * | ||

| Improved | 6 | 32 | |

| Maintained | 24 | 27 | |

| Worsened | 24 | 6 | |

| Ambulation recovery | 0.017 * | ||

| Success | 21 | 40 | |

| Failure | 33 | 25 | |

| Local progression | 11(20.3%) | 15 (23.1%) | 0.825 |

| Survival period | 6.31 ± 6.01 | 7.55 ± 7.17 | 0.600 |

| Complications | 2 | 5 | 0.454 |

| Patient Treated with Operation | |

| Operation Approach | |

| Anterior | 5 (7.7%) |

| Posterior | 57 (88.6%) |

| Combined | 3 (4.6%) |

| Operation type | |

| Laminectomy | 2 (3%) |

| Laminectomy and fusion | 59 (90.8%) |

| Corpectomy | 4 (6.2%) |

| Postop RT | |

| Yes | 43 (66.2%) |

| No | 22 (33.8%) |

| RT type | |

| EBRT | 25 (58.1%) |

| SBRT | 18 (41.9%) |

| Patient treated with Radiotherapy | |

| RT type | |

| EBRT | 30 (55.6%) |

| SBRT | 24 (44.4%) |

| All Patients | Univariate OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 0.73 | ||

| Sex (F) | 0.60 (0.22–1.65) | 0.32 | — | — |

| DM | 3.00 (1.07–8.40) | 0.037 * | 2.89 | 0.050 * |

| HTN | 0.55 (0.19–1.61) | 0.28 | — | — |

| Smoking | 1.06 (0.44–2.56) | 0.89 | — | — |

| Pathology | 0.82 (0.39–1.73) | 0.36 | — | — |

| ECOG | 0.99 (0.68–1.45) | 0.96 | — | — |

| Initial motor power | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) | 0.44 | — | — |

| Tumor Location (Cervical, Thoracic, Multiple) | 1.12 (0.79–1.59) | 0.52 | — | — |

| Pathologic Fx | 1.00 | 0.09 | — | — |

| Compression direction (Ant, post, circumferential) | 1.00 | 0.33 | — | — |

| SINS total score | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 0.81 | — | — |

| Initial Tx (Surgery vs. RT) | 1.17 (0.49–2.82) | 0.72 | — | — |

| RT modality (SBRT) | 0.89 (0.35–2.23) | 0.80 | — | — |

| Surgery Group | ||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 0.64 | — | — |

| Sex (F) | 0.64 (0.16–2.63) | 0.54 | — | — |

| DM | 1.91 (0.48–7.52) | 0.36 | — | — |

| HTN | 0.49 (0.10–2.47) | 0.39 | — | — |

| Smoking | 1.86 (CI 0.58–5.97) | 0.29 | — | — |

| ECOG | 1.03 (0.60–1.75) | 0.92 | — | — |

| Initial motor grade | 0.82 (0.56–1.20) | 0.31 | — | — |

| Tumor Location (Cervical, Thoracic, Multiple) | — | 0.49 | — | — |

| Pathologic Fx | 1.12 (0.33–3.81) | 0.85 | — | — |

| Compression direction (Ant, post, circumferential) | — | 0.13 | — | — |

| SINS total | 0.99 (0.81–1.21) | 0.90 | — | — |

| Postoperative RT | 0.32 (0.10–1.06) | 0.061 * | 0.29 (0.08–1.03) | 0.055 * |

| Surgery type | — | 0.73 | — | — |

| RT Group | ||||

| Age | 1.003 (0.95–1.06) | 0.92 | — | — |

| Sex (F) | 0.57 (0.13–2.47) | 0.46 | — | — |

| DM | 5.57 (1.12–27.66) | 0.036 ** | 5.44 (1.02–29.00) | 0.047 ** |

| HTN | 0.63 (0.15–2.74) | 0.54 | — | — |

| Smoking | 0.47 (0.11–2.03) | 0.31 | — | — |

| Pathology | — | 0.21 | — | — |

| ECOG | 0.95 (0.55–1.64) | 0.86 | — | — |

| Tumor Location (Cervical, Thoracic, Multiple) | — | 0.47 | — | — |

| Pathologic Fx | 0.76 (0.20–2.87) | 0.68 | — | — |

| Compression direction (Ant, post, circumferential) | — | 0.67 | — | — |

| SINS total | 0.97 (0.79–1.19) | 0.78 | — | — |

| RT modality (SBRT) | 0.66 (0.17–2.58) | 0.55 | — | — |

| Dose per Fraction | 1.00 (0.994–1.006) | 0.55 | — | — |

| Total Radiation Dose | 1.00 (0.997–1.014) | 0.17 | — | — |

| All Patients (N = 80) | Univariate OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.11 (0.97–1.04) | 0.812 | ||

| Sex (F) | 1.00 (0.46–2.72) | 0.950 | — | — |

| DM | 0.96 (0.32–2.85) | 0.942 | ||

| HTN | 0.56 (0.22–1.44) | 0.23 | — | — |

| Smoking | 0.78 (0.34–1.80) | 0.56 | — | — |

| Pathology | — | 0.71 | — | — |

| ECOG | 1.24 (0.86–1.80) | 0.25 | — | — |

| Initial motor power | 1.12 (0.87–1.44) | 0.39 | — | — |

| Location (C/T/M) | 0.38 | 0.14 | — | — |

| Pathologic Fx | 1.01 (0.43–2.36) | 0.99 | — | — |

| Compression direction (Ant, post, circumferential) | — | 0.23 | — | — |

| SINS total score | 1.20 (1.03–1.40) | 0.02 * | 1.18 (0.99–1.40) | 0.07 |

| Initial Tx (Surgery) | 9.82 (3.49–27.67) | <0.001 ** | 10.05 (3.36–30.10) | <0.001 ** |

| RT modality (SBRT) | 0.76 (0.31–1.86) | 0.55 | — | — |

| All Patients | Univariate OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment Surgery vs. RT | 2.33 (1.10–4.90) | 0.03 * | 4.33 (1.66–11.29) | 0.003 ** |

| ECOG | 0.47 (0.33–0.68) | <0.001 ** | 0.60 (0.40–0.92) | 0.02 * |

| Initial motor power | 1.57 (1.21–1.99) | <0.001 ** | 1.57 (1.12–2.19) | 0.01 ** |

| Metastasis level Thoracic vs. Cervical | 0.26 (0.07–1.07) | 0.05 * | 0.28 (0.07–1.16) | 0.08 |

| Metastasis level Multiple vs. Cervical | 0.09 (0.01–1.60) | 0.07 | 0.09 (0.01–1.56) | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kwon, K.; Park, S.; Song, M.G.; Park, W.S.; Hwang, C.J.; Lee, D.-H.; Cho, J.H. Clinical Outcomes of Surgery Versus Radiotherapy in Bilsky Grade 3 Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010216

Kwon K, Park S, Song MG, Park WS, Hwang CJ, Lee D-H, Cho JH. Clinical Outcomes of Surgery Versus Radiotherapy in Bilsky Grade 3 Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010216

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Kihyun, Sehan Park, Myeong Geun Song, Wan Soo Park, Chang Ju Hwang, Dong-Ho Lee, and Jae Hwan Cho. 2026. "Clinical Outcomes of Surgery Versus Radiotherapy in Bilsky Grade 3 Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010216

APA StyleKwon, K., Park, S., Song, M. G., Park, W. S., Hwang, C. J., Lee, D.-H., & Cho, J. H. (2026). Clinical Outcomes of Surgery Versus Radiotherapy in Bilsky Grade 3 Metastatic Epidural Spinal Cord Compression. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010216