Frailty Impact on Periprocedural Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Cohort Selection

2.3. Frailty Assessment

2.4. Baseline Variables

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Periprocedural Complications by Frailty

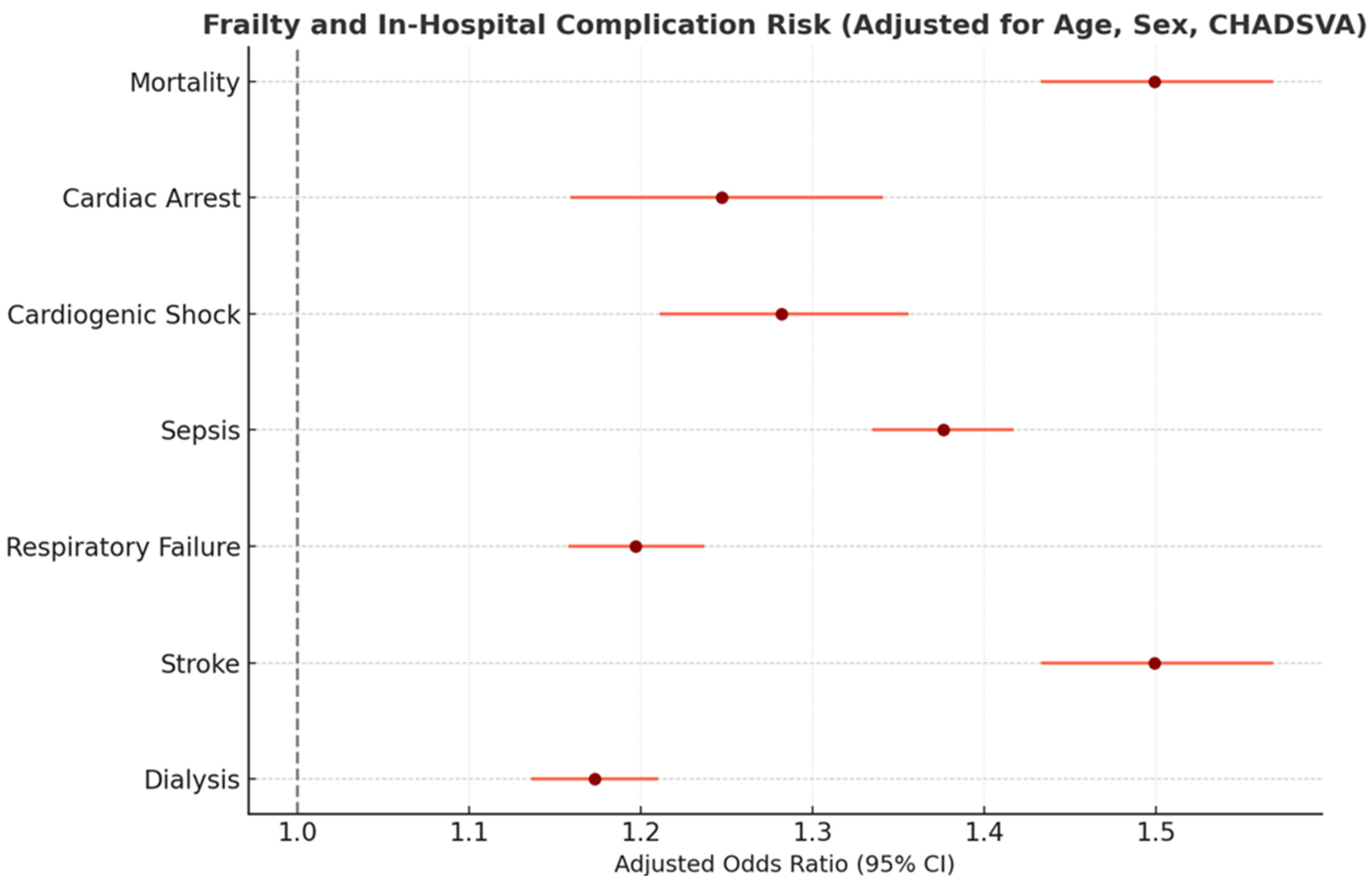

3.3. Multivariable Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afilalo, J.; Alexander, K.P.; Mack, M.J.; Maurer, M.S.; Green, P.; Allen, L.A.; Popma, J.J.; Ferrucci, L.; Forman, D.E. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundi, H.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Valsdottir, L.R.; Shen, C.; Yao, X.; Yeh, R.W.; Kramer, D.B. Relation of frailty to outcomes after catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 125, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Forman, D.E.; van Diepen, S.; Alexander, K.P.; Page, R.L.; Hummel, S.L.; Menon, V.; Katz, J.N.; Albert, N.M.; Afilalo, J.; et al. Older Adults in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit: Factoring Geriatric Syndromes in the Management, Prognosis, and Process of Care: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e6–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.H.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Arocutipa, C.; Carvallo-Castañeda, D.; Chumbiauca, M.; Mamas, M.A.; Hernandez, A.V. Impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent cardiac ablation using a nationwide database. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 203, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Dong, Y.; Yadav, N.; Chen, Q.; Cao, K.; Zhang, F. Prediction of Recurrence of Atrial Fibrillation After Radiofrequency Ablation by Frailty. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e038044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Chen, K.; He, Z.; Chen, D. Impact of frailty on outcomes of elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 41, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, T.; Neuburger, J.; Kraindler, J.; Keeble, E.; Smith, P.; Ariti, C.; Arora, S.; Street, A.; Parker, S.; Roberts, H.C.; et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: An observational study. Lancet 2018, 391, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulai, R.; Uy, C.P.; Sulke, N.; Patel, N.; Veasey, R.A. Frailty status and atrial fibrillation ablation outcomes: A retrospective single-center analysis. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 46, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Kumar, M.; Khlidj, Y.; Hendricks, E.; Farooq, F.; Alruwaili, W.; Keisham, B.; Duhan, S.; Gonuguntla, K.; Sattar, Y.; et al. Impact of frailty in hospitalized patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennberg, A.M.; Ebeling, M.; Ek, S.; Meyer, A.; Ding, M.; Talbäck, M.; Modig, K. Trends in Frailty Between 1990 and 2020 in Sweden Among 75-, 85-, and 95-Year-Old Women and Men: A Nationwide Study from Sweden. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonjour, T.; Waeber, G.; Marques-Vidal, P. Trends in prevalence and outcomes of frailty in a Swiss university hospital: A retrospective observational study. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutrani, H.; Briggs, J.; Prytherch, D.; Andrikopoulou, E.; Spice, C. Using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score to Predict In-Hospital Mortality Across All Ages. In Intelligent Health Systems–From Technology to Data and Knowledge; Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 327, pp. 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaji, O.; Adabale, O.; Bahar, Y.; Echari, B.; Shenoy, V.; Phagoora, J.; Bahar, A.R.; Chadi Alraies, M.; Ayinde, H.; Catanzaro, J.N. Age, Frailty, and Outcomes After Atrial Fibrillation Ablation: A Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2025, 36, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Impact of COVID-19 on U.S. Healthcare; CDC WONDER: Online Publication, 2020.

- Reddy, V.Y.; Gerstenfeld, E.P.; Natale, A.; Whang, W.; Cuoco, F.A.; Patel, C.; Mountantonakis, S.E.; Gibson, D.N.; Harding, J.D.; Ellis, C.R.; et al. Pulsed Field or Conventional Thermal Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1660–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Lu, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, J. Meta-analysis of pulsed-field ablation versus cryoablation for atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrouche, N.F.; Brachmann, J.; Andresen, D.; Siebels, J.; Boersma, L.; Jordaens, L.; Merkely, B.; Pokushalov, E.; Sanders, P.; Proff, J.; et al. Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation with Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohns, C.; Fox, H.; Marrouche, N.F.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; Costard-Jaeckle, A.; Bergau, L.; Hindricks, G.; Dagres, N.; Sossalla, S.; Schramm, R.; et al. Catheter Ablation in End-Stage Heart Failure with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Low Frailty (HFRS < 5) (n = 34,265) | Intermediate Frailty (HFRS 5–15) (n = 6425) | High Frailty (HFRS > 15) (n = 2140) | p-Value (Overall) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 66.2 (9.4) | 72.8 (8.3) | 79.4 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, % | 42.3% | 49.8% | 58.1% | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 10.2% | 28.5% | 55.3% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 76.3% | 88.7% | 94.1% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14.0% | 24.6% | 33.8% | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke/TIA | 4.1% | 9.7% | 15.2% | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean | 1.7 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.4) | 4.1 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Primary AF diagnosis (vs secondary) | 85% | 72% | 60% | <0.001 |

| Group as % of total cohort | 80.0% | 15.0% | 5.0% | – |

| Outcome | Low Frailty (HFRS < 5) | Intermediate Frailty (HFRS 5–15) | High Frailty (HFRS > 15) | p-Value (Trend) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality | 1.0% (≈342/34,265) | 2.8% (≈180/6425) | 6.1% (≈130/2140) | <0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke or TIA | 0.3% | 1.1% | 4.0% | <0.001 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 3.5% | 9.8% | 18.0% | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 1.2% | 4.3% | 8.0% | <0.001 |

| Acute dialysis | 0.5% | 1.9% | 4.0% | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0.5% | 1.1% | 3.0% | 0.002 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 0.2% | 0.8% | 2.5% | 0.010 |

| Any major complication | 7.4% | 15.6% | 28.3% | <0.001 |

| Predictor | Intermediate Frailty (vs. Low) | High Frailty (vs. Low) | Female Sex (vs. Male) | Age (per Year) | Heart Failure (CHF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality OR (95% CI) | 2.1 (1.3–3.2) ** | 4.5 (2.8–7.2) ** | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 1.05 (1.03–1.07) ** | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) ** |

| Stroke OR (95% CI) | 3.2 (1.1–8.5) * | 5.5 (2.0–15.2) ** | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) * | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) |

| Resp. Failure OR (95% CI) | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) ** | 4.0 (3.1–5.1) ** | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) * | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) ** | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) ** |

| Sepsis OR (95% CI) | 2.4 (1.8–3.1) ** | 3.7 (2.6–5.3) ** | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) ** | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| Dialysis OR (95% CI) | 3.3 (1.8–6.0) ** | 6.2 (3.2–11.9) ** | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) * | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) |

| Cardiac Arrest OR (95% CI) | 2.0 (0.9–4.1) | 4.1 (1.8–9.3) ** | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 3.0 (1.7–5.2) ** |

| Shock OR (95% CI) | 2.8 (0.8–9.5) | 5.6 (1.5–20.5) ** | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 4.5 (2.1–9.5) ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leshem, E.; Carny, D.; Folman, A.; Kazatsker, M.; Roguin, A.; Margolis, G. Frailty Impact on Periprocedural Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010170

Leshem E, Carny D, Folman A, Kazatsker M, Roguin A, Margolis G. Frailty Impact on Periprocedural Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeshem, Eran, Daniel Carny, Adam Folman, Mark Kazatsker, Ariel Roguin, and Gilad Margolis. 2026. "Frailty Impact on Periprocedural Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010170

APA StyleLeshem, E., Carny, D., Folman, A., Kazatsker, M., Roguin, A., & Margolis, G. (2026). Frailty Impact on Periprocedural Outcomes of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010170