Evaluating the Performance of AI Large Language Models in Detecting Pediatric Medication Errors Across Languages: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Case Development

2.2. AI Tools for Evaluation

2.3. Prompting Procedure and Data Collection

2.4. Classification of Responses

2.5. Reproducibility Testing

2.6. Performance Metrics

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

7. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ML | Machine Learning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| TP | True Positive |

| TN | True Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| HSD | Honestly Significant Difference |

| ANOVA | One-way Analysis of Variance |

| κ | Cohen’s Kappa Statistic |

References

- Hussain, W.; Mabrok, M.; Gao, H.; Rabhi, F.A.; Rashed, E.A. Revolutionising healthcare with artificial intelligence: A bibliometric analysis of 40 years of progress in health systems. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241258757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Salim, N.A.; Barakat, M.; Al-Tammemi, A.B. ChatGPT applications in medical, dental, pharmacy, and public health education: A descriptive study highlighting the advantages and limitations. Narra J. 2023, 3, e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, M.M.; Hobson, C.; GholamHosseini, H.; Ullah, E.; Afifi, S. Generative AI in improving personalized patient care plans: Opportunities and barriers towards its wider adoption. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalhalim, A.Z.A.; Ahmed, S.N.N.; Ezzelarab, A.M.D.; Mustafa, M.; Albasheer, M.G.A.; Ahmed, R.E.A.; Elsayed, M.B.G.E. Clinical Impact of Artificial Intelligence-Based Triage Systems in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e85667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gala, D.; Behl, H.; Shah, M.; Makaryus, A.N. The role of artificial intelligence in improving patient outcomes and future of healthcare delivery in cardiology: A narrative review of the literature. Healthcare 2024, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korteling, J.E.H.; van de Boer-Visschedijk, G.C.; Blankendaal, R.A.M.; Boonekamp, R.C.; Eikelboom, A.R. Human- versus Artificial Intelligence. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 622364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarab, A.S.; Al-Qerem, W.; Al-Hajjeh, D.M.; Abu Heshmeh, S.; Mukattash, T.L.; Naser, A.Y.; Alwafi, H.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N. Artificial intelligence utilization in the healthcare setting: Perceptions of the public in the UAE. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2025, 35, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwunweike, J.N.; Adewale, A.A.; Osamuyi, O. Advanced modelling and recurrent analysis in network security: Scrutiny of data and fault resolution. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 23, 2373–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Arora, C.; Kaushik, R.; Upadhyay, V. Evaluating the impact of data quality on machine learning model performance. J. Nonlinear Anal. Optim. 2023, 1, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrio, F.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Giardino, I.; Masciari, E. The role of artificial intelligence in pediatrics from treating illnesses to managing children’s overall well-being. J. Pediatr. 2024, 275, 114291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno, L.; Caroselli, A.; Tonin, G.; Graglia, B.; Pansini, V.; Causio, F.A.; Gatto, A.; Chiaretti, A. Artificial intelligence in pediatric emergency medicine: Applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.; Godhi, B.S.; Saxena, V.; Assiry, A.A.; Alessa, N.A.; Dawasaz, A.A.; Alqarni, A.; Karobari, M.I. Role of artificial intelligence in behavior management of pediatric dental patients-a mini review. J. Clin. Dent 2024, 48, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mocrii, A.-A.; Chirila, O.-S. AI-assisted application for pediatric drug dosing. In Collaboration Across Disciplines for the Health of People, Animals and Ecosystems; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nada, A.; Ahmed, Y.; Hu, J.; Weidemann, D.; Gorman, G.H.; Lecea, E.G.; Sandokji, I.A.; Cha, S.; Shin, S.; Bani-Hani, S. AI-powered insights in pediatric nephrology: Current applications and future opportunities. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Cotta, M.; Raman, S.; Graham, N.; Schlapbach, L.; Roberts, J.A. Individualized precision dosing approaches to optimize antimicrobial therapy in pediatric populations. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majebi, N.L.; Drakeford, O.M.; Adelodun, M.O.; Chinyere, E. Leveraging digital health tools to improve early detection and management of developmental disorders in children. World J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 4, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, R.L.; Fox, A.; Carrington, A.; Dornan, T.; Lloyd, M. Prescribing errors in children: Why they happen and how to prevent them. Pharm. J. 2021, 306, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Navigli, R.; Conia, S.; Ross, B. Biases in large language models: Origins, inventory, and discussion. ACM J. Data Inf. Qual. 2023, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, C.; Orkaby, B.; Kerner, E.; Saban, M. Can large language models assist with pediatric dosing accuracy? Pediatr. Res. 2025, 98, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, J.C.L.; Jin, L.; Elangovan, K.; San Lim, G.Y.; Lim, D.Y.Z.; Sng, G.G.R.; Ke, Y.H.; Tung, J.Y.M.; Zhong, R.J.; Koh, C.M.Y. Large language model as clinical decision support system augments medication safety in 16 clinical specialties. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar, T.S.; Öcal, O.; Çetinkaya Yaprak, A. Comparison of ChatGPT-4, Microsoft Copilot, and Google Gemini for Pediatric Ophthalmology Questions. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2025, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.H. AI Chatbots in Pediatric Orthopedics: How Accurate Are Their Answers to Parents’ Questions on Bowlegs and Knock Knees? Healthcare 2025, 13, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wei, B.; Li, T.; Xu, X. Evaluation of ChatGPT’s performance in providing treatment recommendations for pediatric diseases. Pediatr. Discov. 2023, 1, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, S.; Ness-Engle, G.L.; Behnen, E.M. A comparison of drug information question responses by a drug information center and by ChatGPT. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2025, 82, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, J.; Margolis, A.; Cason, G.; Kim, R.; Kalash, S.; Tchaconas, A.; Milanaik, R. Diagnostic accuracy of a large language model in pediatric case studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondillo, G.; Perrotta, A.; Colosimo, S.; Frattolillo, V.; Masino, M.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. Artificial intelligence in pediatrics: An opportunity to lead, not to follow. J. Pediatr. 2025, 283, 114641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbaş, K.C.; Yıldız, M.; Saygılı, S.; Canpolat, N.; Kasapçopur, Ö. Artificial intelligence in pediatrics: Learning to walk together. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 59, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, E.A.M.; Gilbert, S.; Koval, I.; Wekenborg, M.K. Alarm fatigue in healthcare: A scoping review of definitions, influencing factors, and mitigation strategies. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Alshuaib, O.; Alhajri, H.; Alotaibi, F.; Alkhurainej, D.; Al-Balwah, M.Y.; Barakat, M.; Egger, J. Language discrepancies in the performance of generative artificial intelligence models: An examination of infectious disease queries in English and Arabic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondillo, G.; Perrotta, A.; Frattolillo, V.; Colosimo, S.; Indolfi, C.; del Giudice, M.M.; Rossi, F. Large language models performance on pediatrics question: A new challenge. J. Med. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, S.; Sengul, A.; Moon, J.; Jackevicius, C.A. Accuracy and reproducibility of ChatGPT responses to real-world drug information questions. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2025, 8, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reviewer Specialty | Cases Reviewed | Revisions Suggested | Actions Taken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 1–15 | Case 8: First-line treatment for bacterial pneumonia is amoxicillin, not ampicillin. | Corrected to amoxicillin. |

| Case 9: Dose calculation exceeds per-dose max (should not exceed 500 mg/dose). | Not changed—exceeding 500 mg/dose is acceptable. | ||

| Case 10: Xopenex (Levalbuterol) is not available. | Not changed—may still be used in other countries. | ||

| Endocrinology | 16–30 | Case 16: Recommend stating that serum thyroid function tests confirmed CH. | Corrected. |

| Case 17: Replace “insulin pens” with “multiple daily injections”. | Corrected. | ||

| Case 22: Add frequency of medications (OD, BID, TID). | Corrected. | ||

| Case 23: Add weight and height. | Corrected. | ||

| Case 26: Mention the starting dose. | Corrected. | ||

| Neurology | 31–45 | Case 35: Use generic name “sodium valproate” instead of “Depakine”. | Not changed—brand name retained for AI recognition. |

| Case 41: Use generic name “vigabatrin” instead of “Sabril®”. | Not changed—brand name retained for AI recognition. | ||

| Case 43: Use “physical examination” and clarify “bid” as “twice daily.” | Corrected. | ||

| Infectious Diseases | 46–60 | Case 47: Urinalysis is suggestive, not confirmatory of UTI. TMP dose is 8 mg/kg/day (not 5), divided BID. | Corrected. |

| Case 51: Clarify that this refers to non-typhi Salmonella, as S. typhi has a different treatment. | Corrected. | ||

| Case 52: Described case is early localized Lyme disease, not early disseminated. | Corrected. | ||

| Case 54: Drug of choice for strep throat is penicillin V or amoxicillin, as Group A strep is most likely. | Corrected. | ||

| Case 55: Theophylline is rarely used in pediatric asthma. | Not changed—still used in select cases. | ||

| Case 58: Azithromycin is not recommended for treating or preventing aspiration pneumonia. Use clindamycin instead. | Corrected—Clindamycin used instead. |

| Case Number | System | Question | Key Answer | Number of Correct Responses (Out of 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | Endocrine | A 6-year-old girl (22 kg) diagnosed with central precocious puberty, with height on the 95th percentile and advanced bone age, was started on Decapeptyl IM 3.75 mg (triptorelin) every 6 months. | Decapeptyl 3.75 mg should be given at an interval of 28 days or less. | 8 |

| 32 | Neurology | A 10-year-old boy was diagnosed with ADHD. Past medical history: episodes of fainting during exercise. Blood pressure was normal for age. ECG: Shows prolonged QT interval (QTc = 500 ms). He was diagnosed with ADHD and prolonged Q-T syndrome. Prescribed Ritalin 10 mg/day. In two divided doses before breakfast and before lunch | Methylphenidate (a stimulant). And other stimulants can increase heart rate and QT interval, raising the risk of torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac death in patients with Long QT syndrome. Clonidine (alph-2 agonist) is a safe choice | 8 |

| 52 | Infectious | A 14-year-old boy (60 kg) was diagnosed with Lyme disease (early localized, erythema migrans with mild systemic symptoms). He was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally once daily for 14 days. | Doxycycline should be 100 mg twice daily for Lyme disease in this age group. | 8 |

| 13 | Respiratory | A 13-year-old girl (45 kg) with fatigue, intermittent fever, and a persistent productive cough. Diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis confirmed by sputum. Started on a four-month regimen: daily isoniazid 300 mg, rifapentine 1200 mg, moxifloxacin 400 mg, and pyrazinamide 1500 mg. | Error free | 1 |

| 51 | Infectious | A 9-year-old girl (30 kg) with recent travel history developed bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and fever. Stool culture was positive for Salmonella non-typhi strains. She was prescribed azithromycin 300 mg orally once daily for day 1 then 150 mg for days 2–3. | Error free | 2 |

| 49 | Infectious | A 3-year-old boy (14 kg) with a history of recurrent skin infections presented with a localized cellulitis. He was prescribed clindamycin 150 mg orally every 8 h. | Error free | 3 |

| AI Tool | Language | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | GPT-5 | English | 60.0% | 66.7% | 55.6% |

| Arabic | 53.3% | 33.3% | 66.7% | ||

| GPT-4o | English | 73.3% | 83.3% | 66.7% | |

| Arabic | 73.3% | 83.3% | 66.7% | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | English | 86.7% | 100.0% | 77.8% | |

| Arabic | 86.7% | 66.7% | 100.0% | ||

| Google Gemini | English | 66.7% | 100.0% | 44.4% | |

| Arabic | 60.0% | 50.0% | 66.7% | ||

| Endocrine | GPT-5 | English | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% |

| Arabic | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% | ||

| GPT-4o | English | 73.3% | 87.5% | 57.1% | |

| Arabic | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | English | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% | |

| Arabic | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% | ||

| Google Gemini | English | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% | |

| Arabic | 80.0% | 87.5% | 71.4% | ||

| Neurology | GPT-5 | English | 93.3% | 87.5% | 100.0% |

| Arabic | 80.0% | 77.8% | 83.3% | ||

| GPT-4o | English | 80.0% | 62.5% | 100.0% | |

| Arabic | 86.7% | 75.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | English | 80.0% | 87.5% | 71.4% | |

| Arabic | 80.0% | 100.0% | 57.1% | ||

| Google Gemini | English | 80.0% | 75.0% | 85.7% | |

| Arabic | 80.0% | 75.0% | 85.7% | ||

| Infectious | GPT-5 | English | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% |

| Arabic | 80.0% | 88.9% | 66.7% | ||

| GPT-4o | English | 80.0% | 62.5% | 100.0% | |

| Arabic | 66.7% | 87.5% | 42.9% | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | English | 93.3% | 100.0% | 85.7% | |

| Arabic | 86.7% | 100.0% | 71.4% | ||

| Google Gemini | English | 73.3% | 87.5% | 57.1% | |

| Arabic | 73.3% | 87.5% | 57.1% |

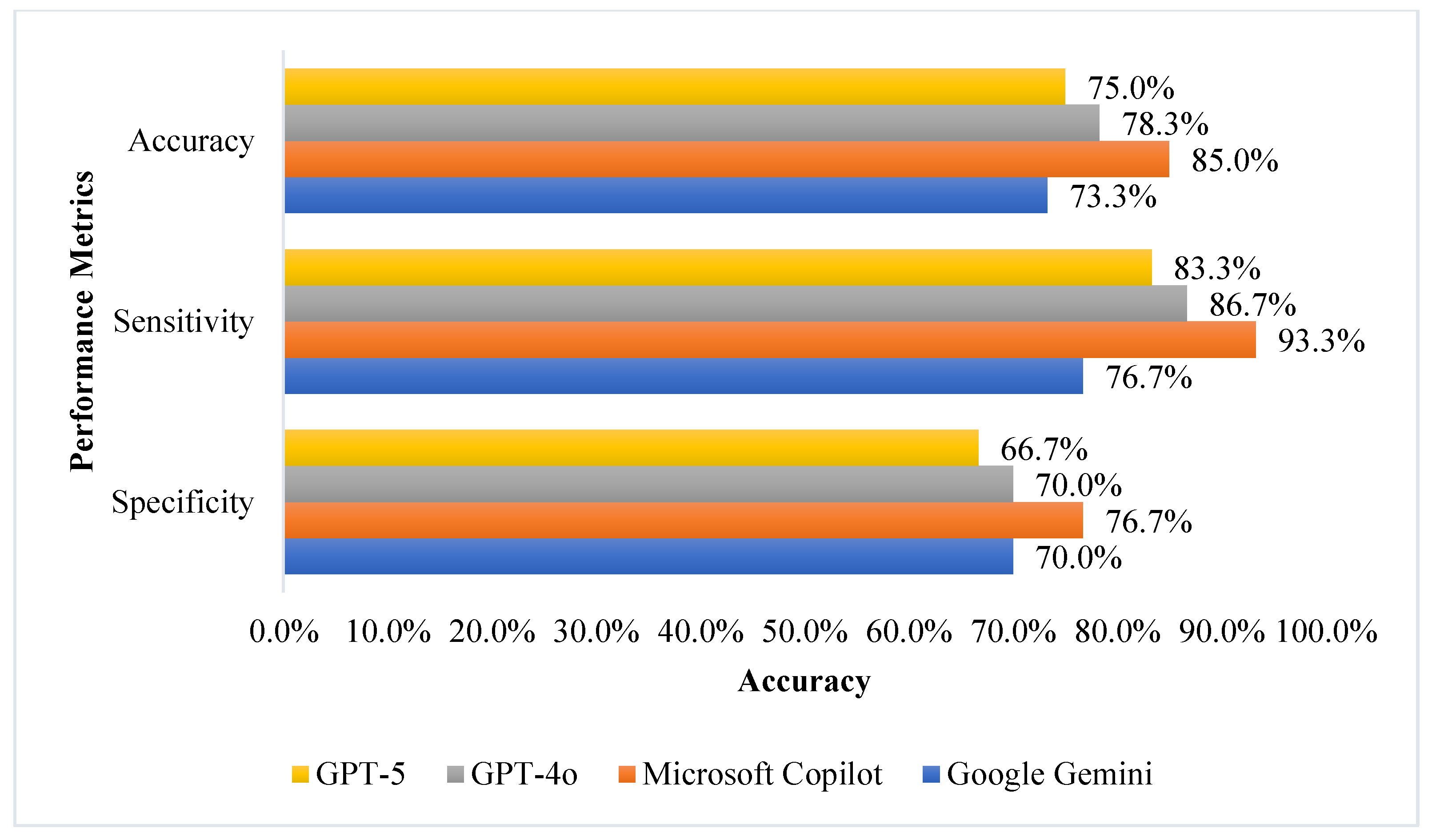

| Metric | Model | Mean ± SD | 95% CI for Mean | p Value # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | GPT-4o | 78.8 ± 2.1 | 75.4–82.1 | 0.005 |

| GPT-5 | 83.4 ± 7.0 | 72.3–94.4 | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | 85.5 ± 1.7 | 82.8–88.1 | ||

| Google Gemini | 73.3 ± 2.7 | 69.0–77.7 | ||

| Sensitivity | GPT-4o | 83.3 ± 8.6 | 69.6–97.0 | 0.037 |

| GPT-5 | 91.7 ± 6.4 | 81.5–100.0 * | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | 92.5 ± 4.2 | 85.8–99.2 | ||

| Google Gemini | 77.5 ± 8.8 | 63.5–91.5 | ||

| Specificity | GPT-4o | 74.2 ± 5.0 | 66.2–82.1 | 0.214 |

| GPT-5 | 75.0 ± 8.4 | 61.6–88.4 | ||

| Microsoft Copilot | 78.4 ± 1.9 | 75.3–81.4 | ||

| Google Gemini | 69.3 ± 5.6 | 60.3–78.2 |

| AI Model | Language | Identical Outputs (n) | Reproducibility Index Between 1st and 2nd Run (%) | Round 1 vs. 2 Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s Kappa (κ) | Cohen’s Kappa (κ) 95% CI | p-Value | ||||

| GPT-5 | English | 52 | 86.6% | 0.783 | 0.654–0.912 | <0.001 |

| Arabic | 46 | 76.6% | 0.645 | 0.496–0.794 | <0.001 | |

| GPT-4o | English | 47 | 78.3% | 0.676 | 0.533–0.819 | <0.001 |

| Arabic | 50 | 83.3% | 0.751 | 0.616–0.886 | <0.001 | |

| Microsoft Copilot | English | 54 | 90.0% | 0.836 | 0.717–0.955 | <0.001 |

| Arabic | 53 | 88.3% | 0.815 | 0.692–0.938 | <0.001 | |

| Google Gemini | English | 42 | 70.0% | 0.567 | 0.414–0.720 | <0.001 |

| Arabic | 42 | 70.0% | 0.573 | 0.416–0.730 | <0.001 | |

| AI Model | Identical Outputs (n) | Reproducibility Index Between English and Arabic for the 1st Run (%) | Intra-Language Agreement for the 1st Run | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s Kappa (κ) | Cohen’s Kappa (κ) 95% CI | p-Value | |||

| GPT-5 | 46 | 76.7% | 0.650 | 0.501–0.799 | <0.001 |

| GPT-4o | 41 | 68.3% | 0.532 | 0.375–0.689 | <0.001 |

| Microsoft Copilot | 49 | 81.7% | 0.701 | 0.556–0.846 | <0.001 |

| Google Gemini | 44 | 73.3% | 0.610 | 0.457–0.763 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abu-Farha, R.K.; Abuzaid, H.; Alalawneh, J.; Sharaf, M.; Al-Ghawanmeh, R.; Qunaibi, E.A. Evaluating the Performance of AI Large Language Models in Detecting Pediatric Medication Errors Across Languages: A Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010162

Abu-Farha RK, Abuzaid H, Alalawneh J, Sharaf M, Al-Ghawanmeh R, Qunaibi EA. Evaluating the Performance of AI Large Language Models in Detecting Pediatric Medication Errors Across Languages: A Comparative Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu-Farha, Rana K., Haneen Abuzaid, Jena Alalawneh, Muna Sharaf, Redab Al-Ghawanmeh, and Eyad A. Qunaibi. 2026. "Evaluating the Performance of AI Large Language Models in Detecting Pediatric Medication Errors Across Languages: A Comparative Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010162

APA StyleAbu-Farha, R. K., Abuzaid, H., Alalawneh, J., Sharaf, M., Al-Ghawanmeh, R., & Qunaibi, E. A. (2026). Evaluating the Performance of AI Large Language Models in Detecting Pediatric Medication Errors Across Languages: A Comparative Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010162