Real-World Retrospective Report on the Efficacy, Tolerability, and Molecular Responses to Ropeginterferon-α2b in Patients with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics at Ropeg-IFNa Initiation

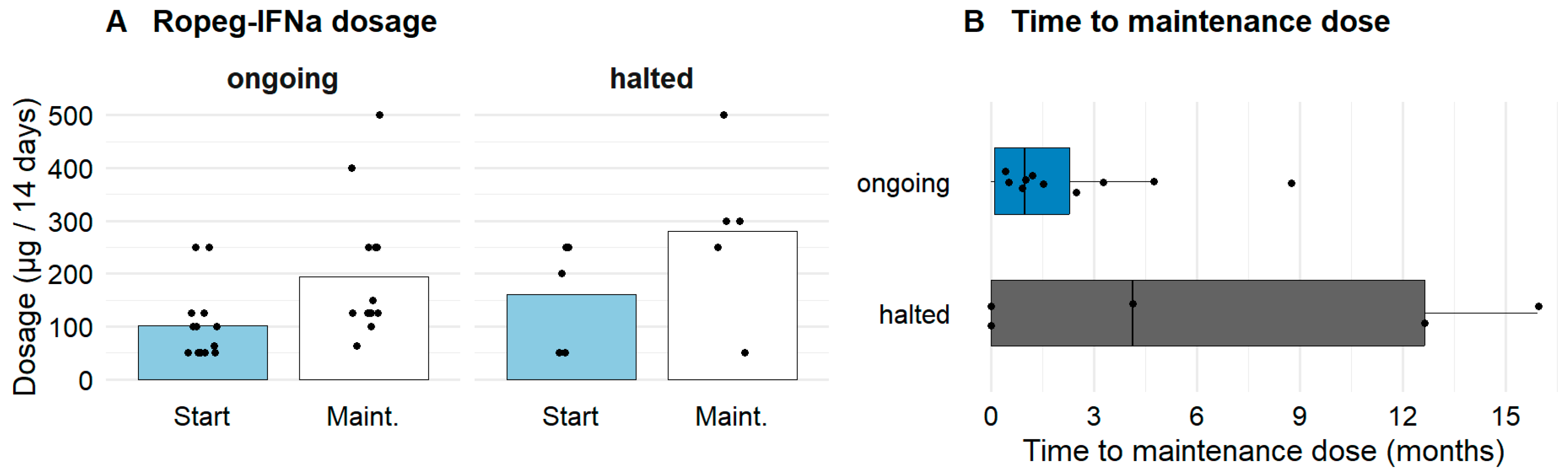

3.2. Characteristics of Ropeg-IFNa Administration

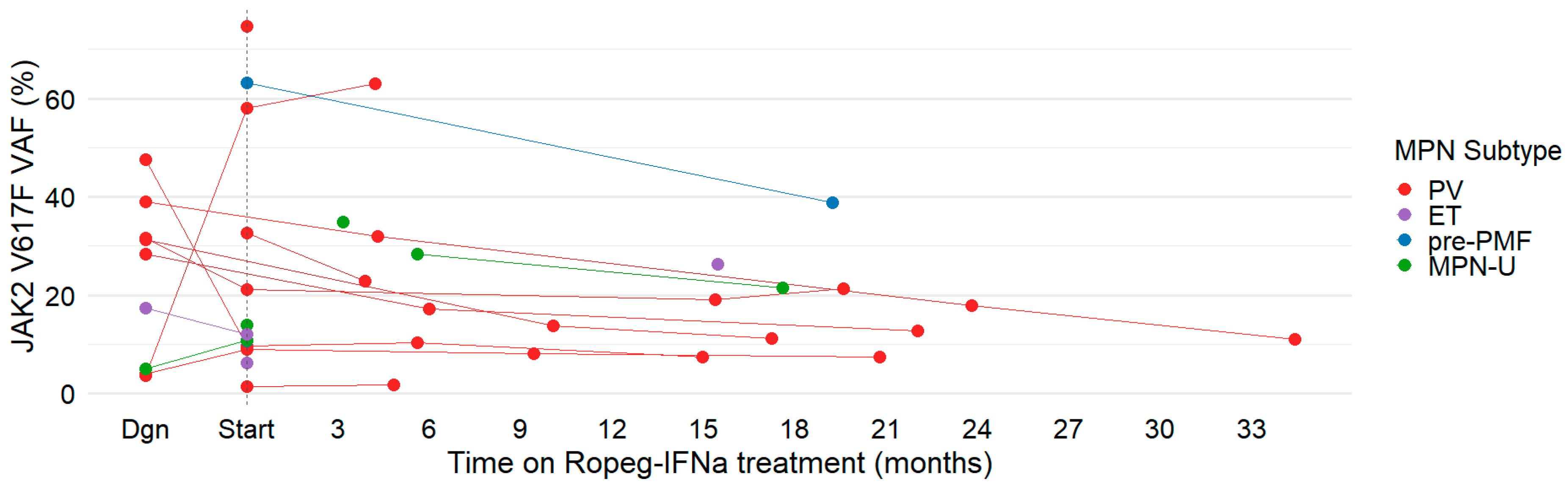

3.3. Hematologic and Molecular Responses to Ropeg-IFNa

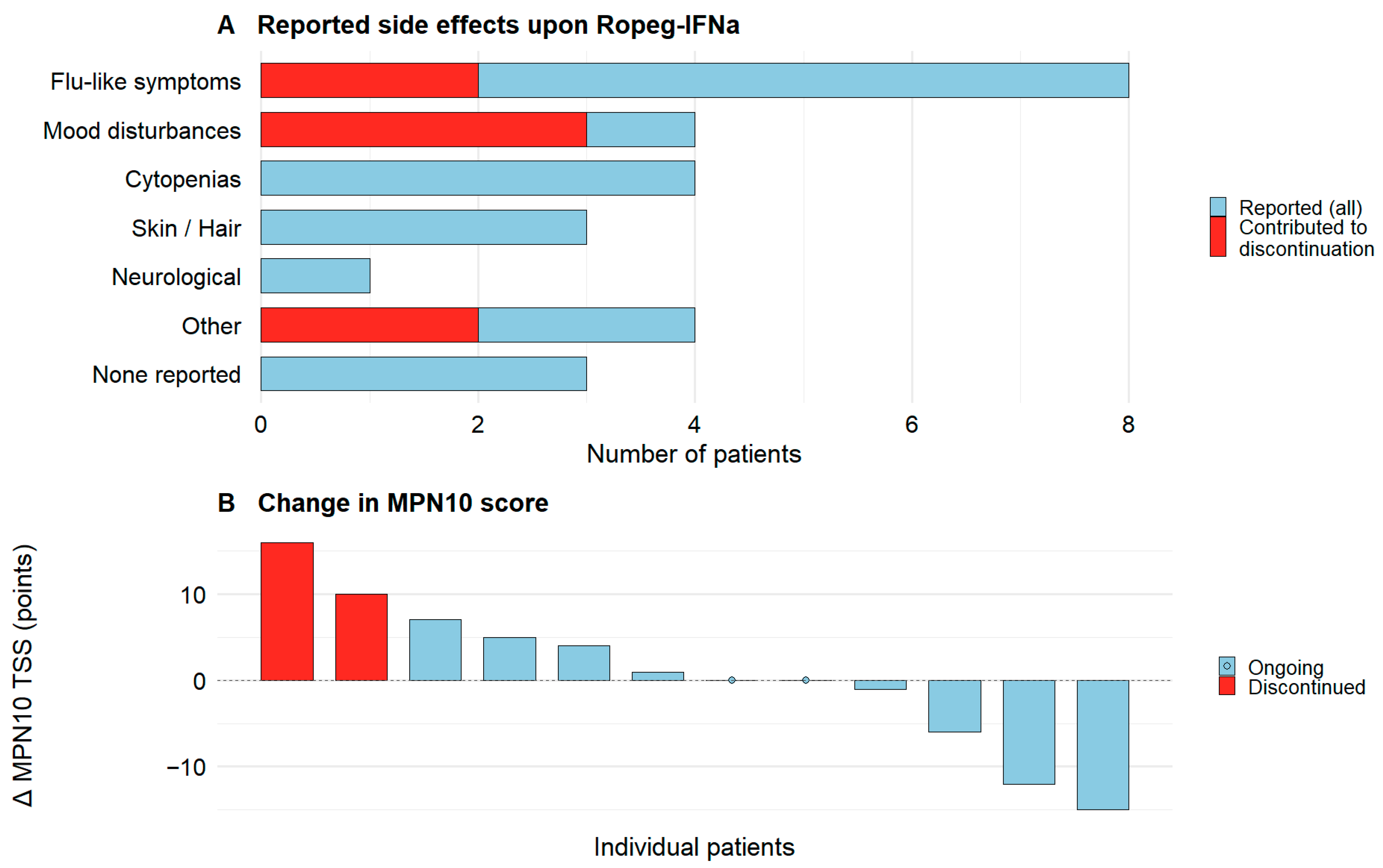

3.4. Side Effects of Ropeg-IFNa Treatment in MPN

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| ET | Essential Thrombocythemia |

| IFNa | Interferon-Alpha |

| MPN | Myeloproliferative Neoplasm |

| MPN-U | MPN unclassifiable |

| Pre-PMF | Prefibrotic Primary Myelofibrosis |

| PV | Polycythemia Vera |

| Ropeg-IFNa | Ropeginterferon alfa-2b |

| VAF | Variant Allele Frequency |

References

- Spivak, J.L. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2168–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampal, R.; Al-Shahrour, F.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Patel, J.P.; Brunel, J.-P.; Mermel, C.H.; Bass, A.J.; Pretz, J.; Ahn, J.; Hricik, T.; et al. Integrated genomic analysis illustrates the central role of JAK-STAT pathway activation in myeloproliferative neoplasm pathogenesis. Blood 2014, 123, e123-33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szybinski, J.; Meyer, S.C. Genetics of Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 35, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, C.N.; Garcia, N.C. Management of MPN beyond JAK2. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2014, 2014, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.H.; Koren-Michowitz, M.; Lavi, N.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Mesa, R.; Harrison, C.N. Ruxolitinib for the management of myelofibrosis: Results of an international physician survey. Leuk. Res. 2017, 61, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefferi, A.; Alkhateeb, H.; Gangat, N. Blast phase myeloproliferative neoplasm: Contemporary review and 2024 treatment algorithm. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachhani, P.; Mascarenhas, J.; Bose, P.; Hobbs, G.; Yacoub, A.; Palmer, J.M.; Gerds, A.T.; Masarova, L.; Kuykendall, A.T.; Rampal, R.K.; et al. Interferons in the treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2024, 15, 20406207241229588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiladjian, J.-J.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; Sivcheva, L.; et al. Long-term outcomes of polycythemia vera patients treated with ropeginterferon Alfa-2b. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1408–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisslinger, H.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Rossiev, V.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): A randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e196–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisslinger, H.; Klade, C.; Georgiev, P.; Krochmalczyk, D.; Gercheva-Kyuchukova, L.; Egyed, M.; Dulicek, P.; Illes, A.; Pylypenko, H.; Sivcheva, L.; et al. Event-free survival in patients with polycythemia vera treated with ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus best available treatment. Leukemia 2023, 37, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucine, N.; Jessup, J.A.; Cooper, T.M.; Urbanski, R.W.; Kolb, E.A.; Resar, L.M.S. Position paper: The time for cooperative group study of ropeginterferon alfa-2b in young patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms is now. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70, e30559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Vannucchi, A.M.; De Stefano, V.; Carobbio, A.; Ghirardi, A.; Carioli, G.; Masciulli, A.; Rossi, E.; Ciceri, F.; Bonifacio, M.; et al. Ropeginterferon versus Standard Therapy for Low-Risk Patients with Polycythemia Vera. NEJM Evid. 2023, 2, EVIDoa2200335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-E.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Hsu, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tsou, H.-Y.; Li, C.-P.; Lai, Y.-H.; Lu, C.-H.; Chen, P.-T.; Chen, C.-C. Real-world experience with Ropeginterferon-alpha 2b (Besremi) in Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okikiolu, J.; Woodley, C.; Cadman-Davies, L.; O’Sullivan, J.; Radia, D.; Garcia, N.C.; Harrington, P.; Kordasti, S.; Asirvatham, S.; Sriskandarajah, P.; et al. Real world experience with ropeginterferon alpha-2b (Besremi) in essential thrombocythaemia and polycythaemia vera following exposure to pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys). Leuk. Res. Reports 2023, 19, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova-Labachevska, M.; Cvetanoski, M.; Ridova, N.; Trajkova, S.; Stojanovska-Jakimovska, S.; Mojsovska, T.; Stojanoski, Z.; Pivkova-Veljanovska, A.; Panovska-Stavridis, I. Effectiveness of Ropeginterferon Alfa-2B in High-Risk Patients with Philadelphia Chromosome Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms– Evaluation of Clinicohaematologic Response, and Safety Profile: Single Centre Experience. PRILOZI 2023, 44, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palandri, F.; Branzanti, F.; Venturi, M.; Dedola, A.; Fontana, G.; Loffredo, M.; Patuelli, A.; Ottaviani, E.; Bersani, M.; Reta, M.; et al. Real-life use of ropeg-interferon α2b in polycythemia vera: Patient selection and clinical outcomes. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 2347–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarova, L.; Patel, K.P.; Newberry, K.J.; Cortes, J.; Borthakur, G.; Konopleva, M.; Estrov, Z.; Kantarjian, H.; Verstovsek, S. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a in patients with essential thrombocythaemia or polycythaemia vera: A post-hoc, median 83 month follow-up of an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet. Haematol. 2017, 4, e165–e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yacoub, A.; Mascarenhas, J.; Kosiorek, H.; Prchal, J.T.; Berenzon, D.; Baer, M.R.; Ritchie, E.; Silver, R.T.; Kessler, C.; Winton, E.; et al. Pegylated interferon alfa-2a for polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia resistant or intolerant to hydroxyurea. Blood 2019, 134, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, H.; Masarova, L.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Komatsu, N.; Jin, J.; Kirito, K.; Ohishi, K.; Shirane, S.; Tashi, T.; et al. Better Safety and Efficacy with Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b over Anagrelide as Second-Line Treatment of Essential Thrombocythemia in the Topline Results of the Randomized Phase 3 SURPASS-ET Trial. In Proceedings of the EHA Abstract, Online, 14 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bewersdorf, J.P.; Giri, S.; Wang, R.; Podoltsev, N.; Williams, R.T.; Rampal, R.K.; Tallman, M.S.; Zeidan, A.M.; Stahl, M. Interferon Therapy in Myelofibrosis: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020, 20, e712–e723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.; Yacoub, A.; Tashi, T.; Chai-Ho, W.; Yoon, C.H.; Mascarenhas, J. Navigating the peginterferon Alfa-2a shortage: Practical guidance on transitioning patients to ropeginterferon alfa-2b. Ann. Hematol. 2025, 104, 2571–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Tefferi, A.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Passamonti, F.; Silver, R.T.; Hoffman, R.; Verstovsek, S.; Mesa, R.; Kiladjian, J.-J.; Hehlmann, R.; et al. Philadelphia chromosome-negative classical myeloproliferative neoplasms: Revised management recommendations from European LeukemiaNet. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, M.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Griesshammer, M.; Harrison, C.; Koschmieder, S.; Gisslinger, H.; Álvarez-Larrán, A.; De Stefano, V.; Guglielmelli, P.; Palandri, F.; et al. Appropriate management of polycythaemia vera with cytoreductive drug therapy: European LeukemiaNet 2021 recommendations. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e301–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherber, R.; Dueck, A.C.; Johansson, P.; Barbui, T.; Barosi, G.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Passamonti, F.; Andreasson, B.; Ferarri, M.L.; Rambaldi, A.; et al. The Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Assessment Form (MPN-SAF): International prospective validation and reliability trial in 402 patients. Blood 2011, 118, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Shimoda, K.; Suo, S.; Fu, R.; Kirito, K.; Wu, D.; Liao, J.; Chen, H.; Wu, L.; Su, X.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics-Pharmacodynamics and Exposure-Response of Ropeginterferon Alfa-2b in Chinese and Japanese Patients With Polycythemia Vera. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2025, 13, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, A.L.; Skov, V.; Kjær, L.; Bjørn, M.E.; Eickhardt-Dalbøge, C.S.; Larsen, M.K.; Nielsen, C.H.; Thomsen, C.; Rahbek Gjerdrum, L.M.; Knudsen, T.A.; et al. Combination therapy with ruxolitinib and pegylated interferon alfa-2a in newly diagnosed patients with polycythemia vera. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 5416–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compendium—Fachinformation Besremi. 2025. Available online: https://compendium.ch/product/1450797-besremi-inj-los-250-mcg-0-5-ml/mpro (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. EMA—Besremi: EPAR—Product Information. 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/besremi-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

| Variable | All Patients (n = 20) | PV (n = 11) | ET (n = 3) | Pre-PMF (n = 2) | MPN-U (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 52.9 (34–77) | 51.9 (34–77) | 57 (38–70) | 49 (43–55) | 54.5 (38–70) |

| Sex, n (M/F) | 11/9 | 7/4 | 2/1 | 1/1 | 1/3 |

| Disease duration, (months) median (range) | 21.5 (2–300) | 35 (6–300) | 5 (4–32) | 3 (2–4) | 60 (6–96) |

| Hematocrit (%), mean ± SD | 41.4 ± 4.6 | 42.0 ± 4.5 | 42.3 ± 5.5 | 37.5 ± 6.4 | 41.0 ± 4.3 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L), mean ± SD | 138.0 ± 13.2 | 140.0 ± 10.4 | 143.0 ± 20.6 | 122.5 ± 13.4 | 142.7 ± 16.4 |

| Leukocyte count (G/L), mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 3.4 | 5.9 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 9.8 ± 4.5 | 9.0 ± 6.1 |

| Platelet count (G/L), mean ± SD | 417.6 ± 287.6 | 385.1 ± 371.9 | 489.3 ± 85.2 | 524.0 ± 223.4 | 383.0 ± 149.8 |

| JAK2 V617F VAF analysis performed, n (%) | 13 (65) | 7 (64) | 2 (67) | 2 (100) | 2 (50) |

| JAK2 V617F VAF %, median (range) | 12.0 (1.4–74.6) | 21.2 (1.4–74.6) | 9.1 (6.3–12.0) | 37.0 (10.8–63.2) | 12.4 (10.9–14.0) |

| Additional mutations in NGS (positive/tested) | 5/9 | ASXL1, DNMT3A (2/4) | EZH2, ASXL1 (1/2) | None (0/1) | BCOR, TET2, NF1 (2/2) |

| MPN10 SAF analysis performed, n (%) | 12 (55) | 6 (55) | 2 (67) | 1 (50) | 3 (75) |

| MPN10 SAF median (range) | 5.5 (0–36) | 5.0 (3–15) | 18 (0–36) | 0 | 6 (5–24) |

| ELN thrombotic risk score (high vs. low) | 11/9 | 3/8 | 3/0 | 1/1 | 4/0 |

| Patients with previous thromboembolism (n, %) | 10 (50) | 2 (18) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | 4 (100) |

| Previous cytoreductive therapy (n, %) * | 18 (90) | 10 (91) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 3 (75) |

| Previous phlebotomy (n, %) | 9 (45) | 8 (73) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Previous hydroxyurea (n, %) | 13 (65) | 6 (55) | 3 (100) | 2 (100) | 2 (50) |

| Previous pegylated interferon alfa-2a (n, %) | 8 (40) | 8 (73) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Previous JAK2 inhibition (n, %) | 2 (10) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Previous anticoagulation (n, %) | 10 (50) | 3 (27) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) |

| Previous antiaggregation (n, %) | 8 (40) | 6 (55) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Ropeg-IFNa starting dose (µg Q2W, mean ± SD) | 115.7 ± 78.7 | 155.7 ± 85.7 | 66.7 ± 28.9 | 75 ± 35.4 | 62.5 ± 25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Christen, M.; Kaderli, D.; Ratknic, M.; de Angelis, A.D.; Aebi, P.S.; Porret, N.; Tchinda, J.; Baran, N.; Rim, W.; Tanner, P.J.; et al. Real-World Retrospective Report on the Efficacy, Tolerability, and Molecular Responses to Ropeginterferon-α2b in Patients with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010128

Christen M, Kaderli D, Ratknic M, de Angelis AD, Aebi PS, Porret N, Tchinda J, Baran N, Rim W, Tanner PJ, et al. Real-World Retrospective Report on the Efficacy, Tolerability, and Molecular Responses to Ropeginterferon-α2b in Patients with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristen, Matthias, Domenic Kaderli, Milos Ratknic, Adrián Dante de Angelis, Philipp Stefan Aebi, Naomi Porret, Joëlle Tchinda, Natalia Baran, Wuddri Rim, Pascale Julia Tanner, and et al. 2026. "Real-World Retrospective Report on the Efficacy, Tolerability, and Molecular Responses to Ropeginterferon-α2b in Patients with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010128

APA StyleChristen, M., Kaderli, D., Ratknic, M., de Angelis, A. D., Aebi, P. S., Porret, N., Tchinda, J., Baran, N., Rim, W., Tanner, P. J., Mathes, S., Angelillo-Scherrer, A., Rovó, A., & Meyer, S. C. (2026). Real-World Retrospective Report on the Efficacy, Tolerability, and Molecular Responses to Ropeginterferon-α2b in Patients with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010128