Unravelling the Mystery of Psoriasis Dermatitis (PsoDermatitis): A Practical Guide to Recognition and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Nomenclature

3.2. Epidemiology

3.2.1. Non-Drug-Related PsoDermatitis

3.2.2. PsoDermatitis as a Paradoxical Reaction (Drug-Related PsoDermatitis)

- PsoDermatitis associated with biological drugs used to treat Pso

- PsoDermatitis associated with biological drugs used to treat AD

3.3. Genetics

3.4. The Immunological Spectrum

3.5. Pathogenesis

3.5.1. Non-Drug-Related PsoDermatitis

3.5.2. Drug-Related PsoDermatitis

- PsoDermatitis associated with biological drugs used to treat Pso

- PsoDermatitis associated with biological drugs used to treat AD

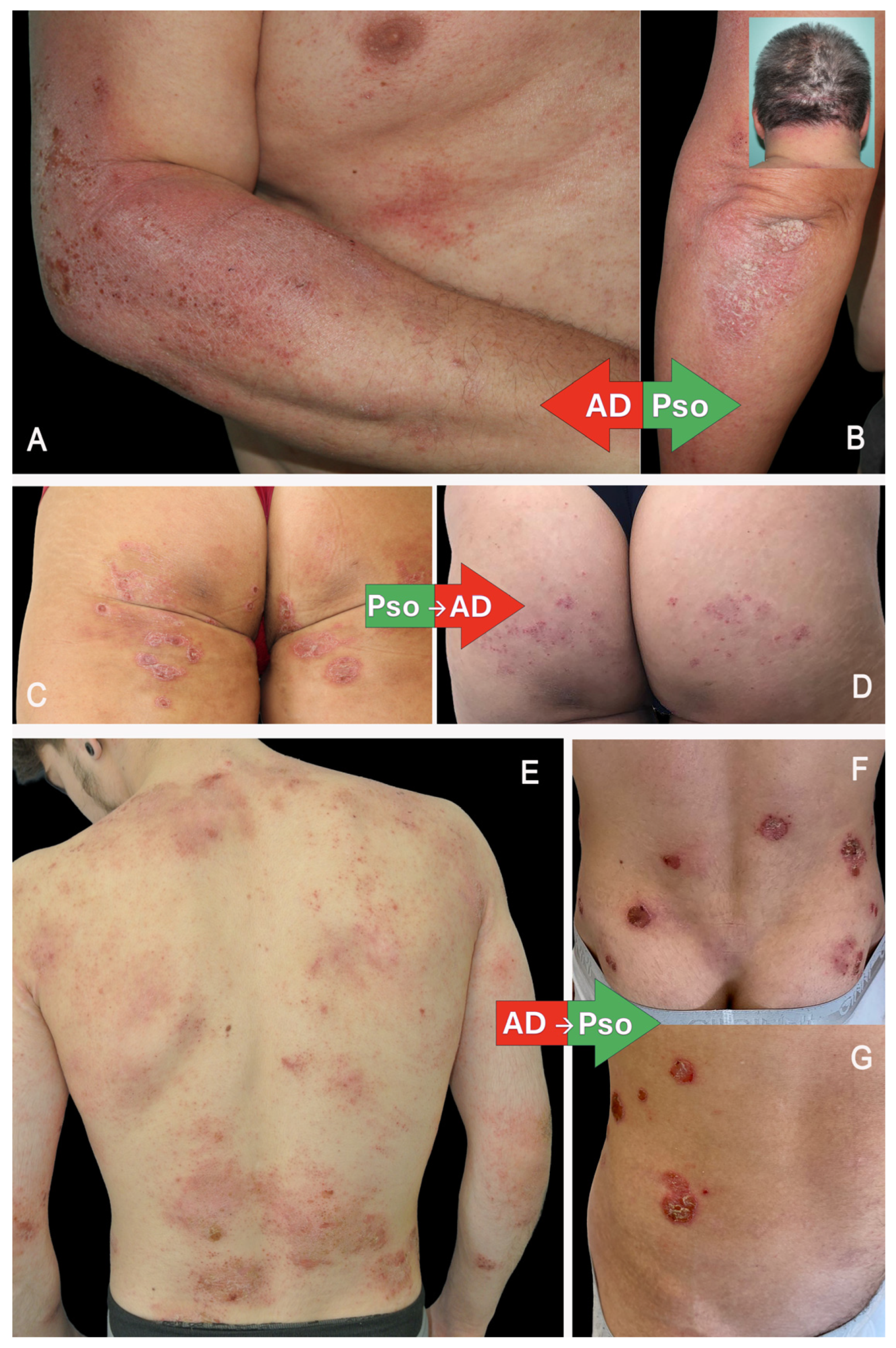

3.6. Clinical and Histological Manifestations

3.6.1. PsoDermatitis Associated with Biological Drugs Used to Treat Pso

3.6.2. PsoDermatitis Associated with Biological Drugs Used to Treat AD

3.7. Clinical Implications and Management

3.7.1. Recognition: How to Perform a Differential Diagnosis

3.7.2. Prevention

- Before Receiving Biologics for Pso

- Before Receiving Biologics for AD

3.8. Treatment (Figure 2)

3.8.1. Non-Drug-Related PsoDermatitis

3.8.2. Drug-Related PsoDermatitis

- Combination of Monoclonal Antibodies (CMAs)—combined targeted therapies that comprise both immunological axes. If the underlying disease for which biological therapy was initiated is well controlled—particularly in the case of multi-failure patients—the addition of another targeted therapy appears to be a reasonable option. This approach has been shown to be safe and effective, although it raises concerns with regard to economic sustainability [41].

- PsoDermatitis associated with anti TNF-alpha—consider JAKis, CMAs or a swap for anti-IL-23. The latter is based on the observation that paradoxical eczema risk seems to be lowest in patients receiving IL-23 inhibitors [11].

- PsoDermatitis associated with anti-IL-17—consider JAKi, CMA or a swap for anti-IL-23. In the case of PsoDermatitis associated with anti-IL-17A, broader IL-17 pathway inhibition may help to prevent this adverse event; therefore, the use of brodalumab may be considered, as it targets the IL-17 receptor A (IL-17RA) and thereby blocks multiple IL-17 isoforms, including IL-17C and IL-17E (the latter is involved in Th2-mediated inflammation).

- PsoDermatitis associated with anti-IL-23: consider JAKi or CMA.

- PsoDermatitis associated with anti-IL-4/13: Consider JAKi or CMA. Despite the paucity of reported cases—and due to the recent approval of these drugs—the development of PsoDermatitis has also been associated with selective IL-13 inhibition by tralokinumab. To date, no such reports have been documented for lebrikizumab [42].

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Atopic Dermatitis. |

| Pso | Psoriasis. |

| JAKs | Janus Kinases. |

| CMA | Combination of Monoclonal Antibodies |

References

- Barry, K.; Zancanaro, P.; Casseres, R.; Abdat, R.; Dumont, N.; Rosmarin, D. Concomitant atopic dermatitis and psoriasis—A retrospective review. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramovits, W.; Cockerell, C.; Stevenson, L.C.; Goldstein, A.M.; Ehrig, T.; Menter, A. PsEma—A hitherto unnamed dermatologic entity with clinical features of both psoriasis and eczema. SKINmed Dermatol. Clin. 2005, 4, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestri, R.; Magnano, M.; Girardelli, C.R.; Bortolotti, R.; Rech, G. Long-term safety of combined biological therapy in a patient affected by arthropathic psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunliffe, A.; Gran, S.; Ali, U.; Grindlay, D.; Lax, S.J.; Williams, H.C.; Burden-Teh, E. Can atopic eczema and psoriasis coexist? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Skin Health Dis. 2021, 1, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Henseler, T.; Christophers, E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1995, 32, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.X.; Tai, Y.H.; Chang, Y.T.; Chen, T.J.; Chen, M.H. Bidirectional Association between Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Dermatology 2021, 237, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangge, H.; Gindl, S.; Kenzian, H.; Schauenstein, K. Atopic dermatitis as a side effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 2506–2507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.L.; Davis-Reed, L.; Kimball, A.B. Counter-regulatory balance: Atopic dermatitis in patients undergoing infliximab infusion therapy. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2004, 3, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Lee, K.; Singh, R.; Zhu, T.H.; Farahnik, B.; Abrouk, M.; Koo, J.; Bhutani, T. Eczema as an adverse effect of anti-TNFα therapy in psoriasis and other Th1-mediated diseases: A review. J. Dermatolog Treat. 2017, 28, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Foulkes, A.C.; Mason, K.; Smith, C.H.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Warren, R.B. Phenotypic switch to eczema in patients receiving biologics for plaque psoriasis: A systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Janabi, A.; Alabas, O.A.; Yiu, Z.Z.N.; Foulkes, A.C.; Eyre, S.; Khan, A.R.; Reynolds, N.J.; Smith, C.H.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Warren, R.B. BADBIR Study Group. Risk of Paradoxical Eczema in Patients Receiving Biologics for Psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jaulent, L.; Staumont-Sallé, D.; Tauber, M.; Paul, C.; Aubert, H.; Marchetti, A.; Sassolas, B.; Valois, A.; Nicolas, J.F.; Nosbaum, A. for GREAT Research Group. De novo psoriasis in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab: A retrospective cohort. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, e296–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M.; Scalvenzi, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Cinelli, E.; Patruno, C. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during dupilumab therapy for adult atopic dermatitis: A case series. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M.; Ferrillo, M.; Patruno, C.; Scalvenzi, M.; D’Andrea, M.; Fabbrocini, G. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Clinical Practice: One Year of Experience on 165 Adult Patients from a Tertiary Referral Centre. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 11, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehrmal, S.; Uppal, P.; Nedley, N.; Giesey, R.L.; Delost, G.R. The global, regional, and national burden of psoriasis in 195 countries and territories, 1990 to 2017: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casale, F.; Nguyen, C.; Dobry, A.; Smith, J.; Mesinkovska, N.A. Dupilumab-associated psoriasis and psoriasiform dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2022, 63, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Z.; Zeng, Y.P. Dupilumab-Associated Psoriasis and Psoriasiform Manifestations: A Scoping Review. Dermatology 2023, 239, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Tsai, T.F. Overlapping Features of Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis: From Genetics to Immunopathogenesis to Phenotypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Rodriguez, E.; Degenhardt, F.; Baurecht, H.; Wehkamp, U.; Volks, N.; Szymczak, S.; Swindell, W.R.; Sarkar, M.K.; Raja, K.; et al. Atopic Dermatitis Is an IL-13-Dominant Disease with Greater Molecular Heterogeneity Compared to Psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1480–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cookson, W.O.; Ubhi, B.; Lawrence, R.; Abecasis, G.R.; Walley, A.J.; Cox, H.E.; Coleman, R.; Leaves, N.I.; Trembath, R.C.; Moffatt, M.F.; et al. Genetic linkage of childhood atopic dermatitis to psoriasis susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Li, D.; Shi, D. Skin barrier-inflammatory pathway is a driver of the psoriasis-atopic dermatitis transition. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1335551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Krueger, J.G. Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: Two different immune diseases or one spectrum? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 48, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, S.; Welchowski, T.; Schmid, M.; Maintz, L.; Herrmann, N.; Wilsmann-Theis, D.; Royeck, T.; Havenith, R.; Bieber, T. Development of a clinical algorithm to predict phenotypic switches between atopic dermatitis and psoriasis (the “Flip-Flop” phenomenon). Allergy 2024, 79, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffel, E.; Maier, H.; Riedl, E.; Brüggen, M.C.; Reininger, B.; Schaschinger, M.; Bangert, C.; Guenova, E.; Stingl, G.; Brunner, P.M. Analysis of anti-tumour necrosis factor-induced skin lesions reveals strong T helper 1 activation with some distinct immunological characteristics. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, R.; Wolk, K.; Loyal, L.; Döcke, W.D.; Ghoreschi, K. T cell pathology in skin inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eyerich, S.; Onken, A.T.; Weidinger, S.; Franke, A.; Nasorri, F.; Pennino, D.; Grosber, M.; Pfab, F.; Schmidt-Weber, C.B.; Mempel, M.; et al. Mutual antagonism of T cells causing psoriasis and atopic eczema. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, S.; Honda, T.; Doi, H.; Kabashima, K. Concurrence of psoriasis vulgaris and atopic eczema in a single patient exhibiting different expression patterns of psoriatic autoantigens in the lesional skin. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pichler, W.J. Adverse side-effects to biological agents. Allergy 2006, 61, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.H.; Reynolds, J.M.; Pappu, B.P.; Chen, G.; Martinez, G.J.; Dong, C. Interleukin-17C promotes Th17 cell responses and autoimmune disease via interleukin-17 receptor E. Immunity 2011, 35, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vandeghinste, N.; Klattig, J.; Jagerschmidt, C.; Lavazais, S.; Marsais, F.; Haas, J.D.; Auberval, M.; Lauffer, F.; Moran, T.; Ongenaert, M.; et al. Neutralization of IL-17C Reduces Skin Inflammation in Mouse Models of Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munera-Campos, M.; Ballesca, F.; Richarz, N.; Ferrandiz, C.; Carrascosa, J.M. Paradoxical eczematous reaction to ixekizumab. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, e40–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M.; Megna, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Nisticò, S.P.; Balato, N.; Dastoli, S.; Patruno, C. Eczematous eruption during anti-interleukin 17 treatment of psoriasis: An emerging condition. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 604–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, K.E.; Pupo Wiss, I.M.; Pathoulas, J.T.; Walker, C.J.; Senna, M.M. Dupilumab-induced psoriasis in a patient with atopic dermatitis and alopecia totalis: A case report and literature review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.; Wu, L.; Qiu, Y.; Li, M. Case report: Clinical and histopathological characteristics of psoriasiform erythema and de novo IL-17A cytokines expression on lesioned skin in atopic dermatitis children treated with dupilumab. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 932766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Succaria, F.; Bhawan, J. Cutaneous side-effects of biologics in immune-mediated disorders: A histopathological perspective. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldarola, G.; Pirro, F.; Di Stefani, A.; Talamonti, M.; Galluzzo, M.; D’Adamio, S.; Magnano, M.; Bernardini, N.; Malagoli, P.; Bardazzi, F.; et al. Clinical and histopathological characterization of eczematous eruptions occurring in course of anti IL-17 treatment: A case series and review of the literature. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Felici Del Giudice, M.B.; Ravaglia, G.; Brusasco, M.; Satolli, F. Managing the Overlap: Therapeutic Approaches in Patients with Concomitant Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis-A Case Series. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McInnes, I.B.; Anderson, J.K.; Magrey, M.; Merola, J.F.; Liu, Y.; Kishimoto, M.; Jeka, S.; Pacheco-Tena, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; et al. Trial of Upadacitinib and Adalimumab for Psoriatic Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mease, P.J.; Lertratanakul, A.; Anderson, J.K.; Papp, K.; Van den Bosch, F.; Tsuji, S.; Dokoupilova, E.; Keiserman, M.; Wang, X.; Zhong, S.; et al. Upadacitinib for psoriatic arthritis refractory to biologics: SELECT-PsA 2. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferrucci, S.M.; Buffon, S.; Marzano, A.V.; Maronese, C.A. Phenotypic switch from atopic dermatitis to psoriasis during treatment with upadacitinib. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 986–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gisondi, P.; Maurelli, M.; Costanzo, A.; Esposito, M.; Girolomoni, G. The Combination of Dupilumab with Other Monoclonal Antibodies. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chiei Gallo, A.; Tavoletti, G.; Termini, D.; Marzano, A.V.; Ferrucci, S.M. Tralokinumab-induced psoriasis relapse in a patient with atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 580–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokura, Y.; Hayano, S. Subtypes of atopic dermatitis: From phenotype to endotype. Allergol. Int. 2022, 71, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ranking of Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis Clinical Features | ||

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | Atopic Dermatitis | |

| 1 | Erythrosquamous plaques on the body and/or extremities * | Eczema and/or lichenification of the flexors * |

| 2 | Pustules (facial pustules excluded) * | Dyshidrotic eczema * |

| 3 | Erythema of the rima ani | Dennie–Morgan fold and/or orbital darkening |

| 4 | Scalp infestation beyond the forehead hairline | Perlèche (angular cheilitis) and/or cheilitis * |

| 5 | Plaques psoriasis localized retroauricular | Head and neck dermatitis and/or dirty neck |

| 6 | Psoriatic nail changes (pitting, oil-drop spots, nail plate crumbling) | Keratosis pilaris |

| 7 | Dactylitis/enthesopathy | Personal history for atopy (AST, AD, ARC) |

| 8 | Exacerbation after discontinuation of systemic steroid therapy | Sensitizations/food allergies |

| 9 | Family history of psoriasis | Palmar hyper-linearity |

| 10 | Joint pain | Family history of atopy (AST, AD, ARC, “eczema”) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Balestri, R.; Magnano, M.; Infusino, S.D.; Ioris, T.; Lacava, R.; Girardelli, C.R.; Rech, G. Unravelling the Mystery of Psoriasis Dermatitis (PsoDermatitis): A Practical Guide to Recognition and Management. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010130

Balestri R, Magnano M, Infusino SD, Ioris T, Lacava R, Girardelli CR, Rech G. Unravelling the Mystery of Psoriasis Dermatitis (PsoDermatitis): A Practical Guide to Recognition and Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010130

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalestri, Riccardo, Michela Magnano, Salvatore Domenico Infusino, Tommaso Ioris, Rossella Lacava, Carlo Rene Girardelli, and Giulia Rech. 2026. "Unravelling the Mystery of Psoriasis Dermatitis (PsoDermatitis): A Practical Guide to Recognition and Management" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010130

APA StyleBalestri, R., Magnano, M., Infusino, S. D., Ioris, T., Lacava, R., Girardelli, C. R., & Rech, G. (2026). Unravelling the Mystery of Psoriasis Dermatitis (PsoDermatitis): A Practical Guide to Recognition and Management. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010130