1. Introduction

Mucormycosis is an angioinvasive illness induced by molds from the order Mucorales and is increasingly acknowledged as a significant cause of invasive fungal disease in high-risk individuals [

1]. The disease has a broad clinical spectrum; however, rhino-sinonasal, rhino-orbital, and rhino-orbito-cerebral variants are predominant in otorhinolaryngology, with infection usually initiating in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses before potentially spreading to the orbit and central nervous system. Talmi and associates characterized rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) as a swiftly advancing, frequently lethal infection in immunocompromised individuals, with a death rate over 50% with brain dissemination [

2]. Subsequent studies and evaluations have corroborated the perspective that ROCM constitutes one of the most severe manifestations of fungal sinusitis faced by ENT surgeons [

3].

The epidemiology of mucormycosis has evolved in the last twenty years. Extensive reviews suggest an increasing prevalence, with the illness currently regarded as the third most prevalent invasive mycosis following candidiasis and aspergillosis in certain high-risk groups [

4]. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus has historically been the main risk factor, especially when ketoacidosis is present. However, other factors that significantly increase susceptibility include hematological malignancies, neutropenia, solid organ transplantation, chronic kidney disease, iron overload, and prolonged corticosteroid therapy [

5]. More recent study has revealed a complicated interplay between hyperglycemia, reduced neutrophil activity, and altered iron metabolism, which may produce a permissive environment for Mucorales invasion in the paranasal sinuses and surrounding tissues [

6].

The COVID-19 epidemic has further transformed the picture by magnifying both exposure to steroids and the burden of uncontrolled diabetes. Case data from India and elsewhere reveal surges of ROCM with successive waves of SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly in individuals who previously had systemic corticosteroids or other immunomodulators [

7]. These reports routinely reveal significant rates of sinonasal and orbital involvement, frequent requirement for major surgery, and mortality that can approach 40–50% despite amphotericin-based therapy. At the same time, mucormycosis remains an important opportunistic infection in other immunocompromised groups, including hematology patients and solid organ transplant recipients [

8].

Management recommendations now converge on numerous basic themes. Early diagnosis, swift imaging, histological confirmation, immediate commencement of high-dose liposomal amphotericin B, and aggressive surgical debridement are recognized as the cornerstones of successful therapy [

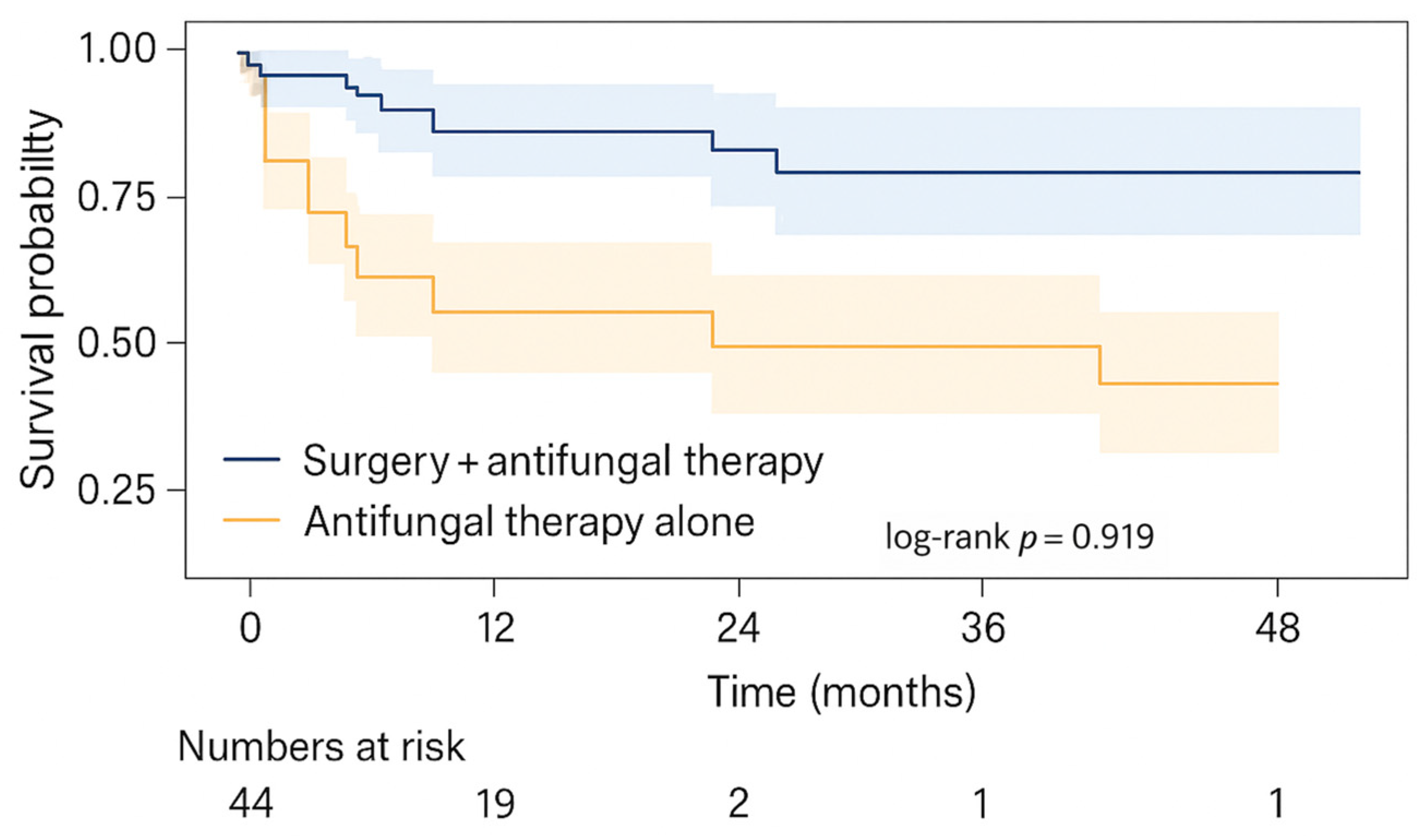

9]. Observational data imply that combination surgical and medicinal treatment is associated with greater survival than either modality alone, although causality remains difficult to prove due to confounding by disease severity [

10]. There is continued disagreement over the proper scope of surgery, especially regarding indications for ocular exenteration, and concerning the function of newer triazoles such as posaconazole and isavuconazole in step-down or salvage regimens [

11].

Despite this growing collection of information, numerous gaps remain. Many published series focus on chosen high-risk populations or brief epidemic episodes, like COVID-associated mucormycosis, rather than presenting long-term institutional data from ENT departments. Moreover, there are relatively few studies that integrate comorbidity profiles, detailed radiological staging, treatment strategies, and survival outcomes in a single cohort, especially from middle-income regions where diabetes is highly prevalent and access to advanced antifungal therapy may be variable [

12].

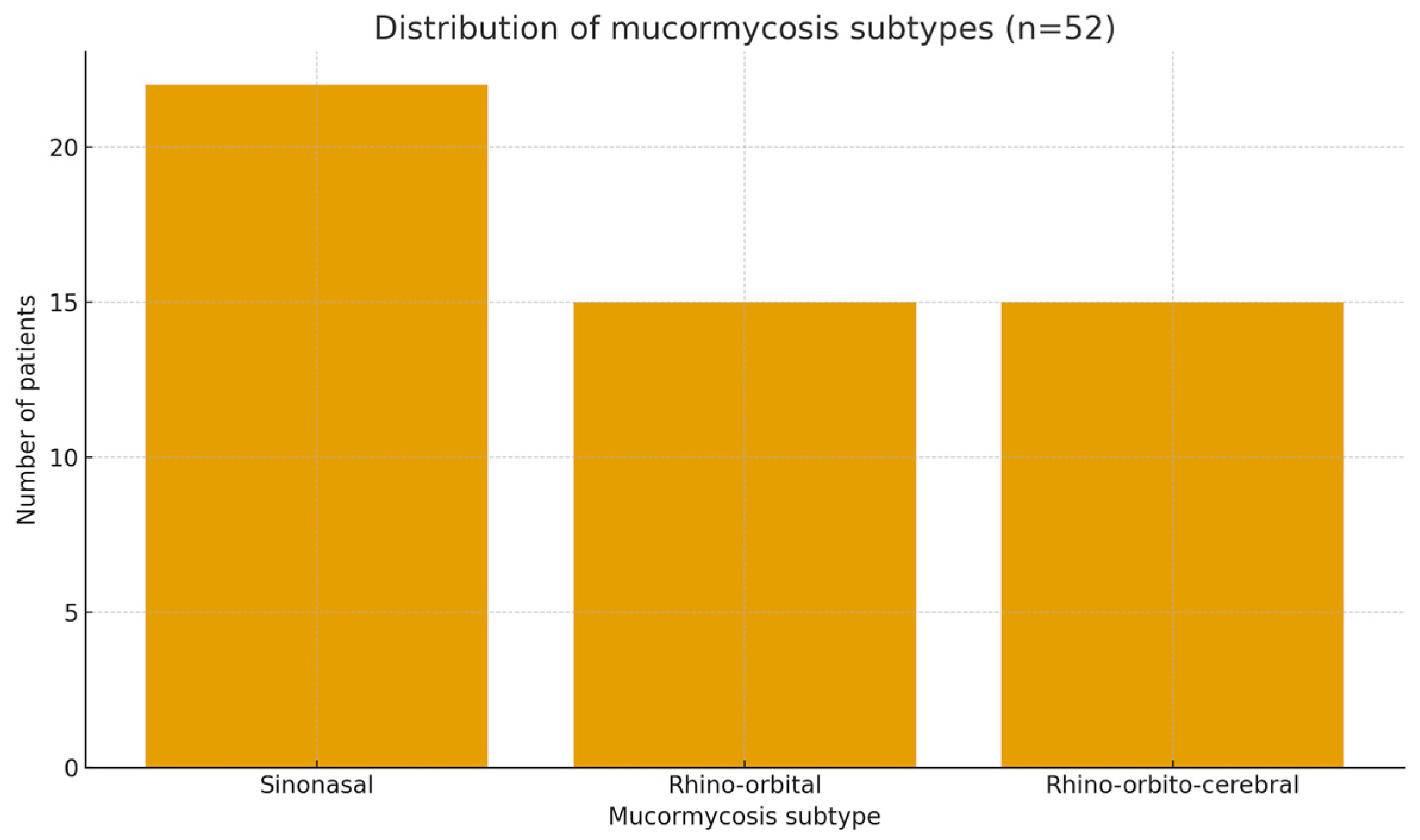

The present study intends to fill part of this gap by retrospectively evaluating all patients with histopathologically proven mucormycosis treated in the Dicle University ENT clinic between 2010 and 2023. We analyze demographic features, comorbidities, mucormycosis subtypes, baseline CT findings, surgical and medicinal therapy, and survival outcomes in a sample of 52 patients. Our fundamental hypothesis is that anatomical extent of disease and treatment strategy will be more significantly related with mortality than individual concomitant conditions, notably diabetes. A further hypothesis is that combination surgery + systemic antifungal therapy will be linked with greater survival compared with antifungal therapy alone, even after accounting for variations in disease stage. By situating these data alongside contemporary international evidence and guideline recommendations, we aim to contribute an ENT-focused perspective on prognostic factors and management strategies in mucormycosis.

2. Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study was designed as a single–center, retrospective quantitative analysis conducted in the Otorhinolaryngology (ENT) Department of Dicle University Faculty of Medicine. Hospital archives and electronic medical records were reviewed to identify all consecutive patients who were evaluated with a preoperative diagnosis of mucormycosis and subsequently treated and followed in the clinic between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2023. The study focuses on relationships between patient comorbidities, radiological extent of disease, treatment modalities and survival outcomes.

Population and Sampling

The target population consisted of adult and pediatric patients of any sex who presented to the ENT clinic within the study period and had histopathologically confirmed mucormycosis. All eligible cases within this timeframe were included in the analysis, so the sample is essentially exhaustive for the department. A priori, a minimum sample size of 52 patients was considered sufficient to provide approximately 80% statistical power to detect clinically meaningful differences in survival across key risk groups, assuming conventional effect sizes and a two sided alpha of 0.05. The final sample met this target (n = 52). The adequacy of the sample size was assessed using power analysis. The power analysis was designed to detect differences in overall survival between predefined clinical subgroups, particularly according to treatment modality and extent of anatomical involvement.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included if they met all of the following criteria:

Presentation to Dicle University ENT clinic with clinical or radiological suspicion of mucormycosis and a subsequent pathology report confirming mucormycosis. All consecutive patients with histopathologically confirmed mucormycosis treated between January 2010 and December 2023 were included. Both adult and pediatric patients were included to ensure an exhaustive representation of all eligible cases managed at our institution during the study period; however, pediatric cases constituted a small proportion of the cohort and were therefore analyzed descriptively rather than as a separate statistical subgroup.

Receipt of either surgical intervention, systemic antifungal therapy, or both, within the ENT or associated departments.

Availability of pre-treatment paranasal sinus computed tomography (CT) imaging suitable for review.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded when any of the criteria below applied:

No histopathological confirmation of mucormycosis despite clinical suspicion.

Lack of active therapeutic intervention, defined as absence of both surgery and systemic antifungal treatment.

Missing or non-retrievable paranasal sinus CT images at baseline.

Variables and Operational Definitions

Key variables were defined and operationalized prior to data extraction.

Demographic factors included age at diagnosis (years) and sex (male or female).

Comorbidities comprised diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive conditions (such as hematologic malignancy, solid organ malignancy, chronic corticosteroid use, organ transplantation), chronic kidney disease and other relevant systemic disorders. Each condition was coded as present or absent based on physician documentation and discharge summaries.

Mucormycosis subtype was categorized according to primary anatomical involvement documented in clinical, radiologic and operative reports (for example, rhino-sinonasal, rhino-orbital, rhino-orbito-cerebral, or other).

Radiologic findings on baseline paranasal sinus CT included the extent of sinus opacification, bony erosion, orbital involvement, intracranial extension and other predefined features. CT examinations were performed using a multidetector CT scanner (e.g., Siemens SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). These variables were coded as binary or ordinal indicators, depending on the level of detail available. Pretreatment paranasal sinus computed tomography (PNS CT) was available for all included patients. Paranasal sinus CT examinations were preferentially performed with intravenous contrast enhancement when not contraindicated; non-contrast CT was obtained in patients with contraindications to contrast administration. CT scans were obtained with intravenous iodinated contrast medium (e.g., Iohexol, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The imaging protocol focused on evaluating sinonasal involvement, bony erosion, orbital extension, and possible intracranial spread.

All patients received systemic antifungal therapy according to institutional protocols. Liposomal amphotericin B (e.g., AmBisome®, Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA) was used as the first-line antifungal agent in all eligible patients. Step-down therapy to oral posaconazole (e.g., Noxafil®, Merck & Co., Kenilworth, NJ, USA) was considered after initial disease control, whereas isavuconazole (e.g., Cresemba®, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA) was reserved for selected cases as an alternative or salvage therapy, particularly in patients with intolerance or contraindications to amphotericin B. The decision to initiate step-down therapy was based on a combination of clinical and logistical criteria, including clinical stabilization, improvement or resolution of endoscopic and/or radiological findings, risk of amphotericin B–related renal toxicity, and feasibility of hospital discharge or outpatient management.

Treatment variables captured whether patients underwent endoscopic sinus surgery, open approaches, orbital procedures (decompression or exenteration), repeated debridements, and the type and duration of systemic antifungal therapy (for example, liposomal amphotericin B, conventional amphotericin B, azoles). Surgical intervention was performed to remove necrotic tissue and to achieve local disease control. In patients with suspected cerebral or skull base involvement, surgical decisions were made within a multidisciplinary team including otorhinolaryngology, neurosurgery, radiology, and infectious diseases specialists. The extent of debridement was planned in a stepwise manner based on the macroscopic boundaries of necrotic tissue. While endoscopic approaches were preferred whenever feasible, combined endoscopic and open techniques were employed in selected cases with extensive disease. In the presence of suspected dural or skull base defects, excessively aggressive resection was avoided to minimize the risk of complications such as cerebrospinal fluid leakage or meningoencephalocele.

The primary outcome of the study was survival. The primary outcome measure was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause or last follow-up. Outcome variables included vital status at last follow up, time from diagnosis to death or censoring (months), and period specific mortality rates. Overall survival was defined as the interval from histopathological diagnosis to death from any cause or last clinical contact.

Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected retrospectively from paper charts, operative notes, pathology reports, radiology information systems and electronic hospital records. A standardized case report form was used to extract demographic data, comorbidities, clinical presentation, imaging findings, operative details, antifungal regimens and follow up information. For radiological variables, pre-treatment paranasal sinus CT scans were retrieved and reviewed. When necessary, missing or ambiguous data were clarified by reexamining original documents. Data entry was performed by two investigators working independently; discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, if needed, consultation with a senior ENT specialist. Cases with irretrievable key information (for example, missing CT images or incomplete survival data) were excluded according to the prespecified criteria. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not routinely performed in all patients but was selectively obtained in cases with clinical or radiological suspicion of orbital apex involvement, cavernous sinus invasion, or central nervous system (CNS) extension, as well as in patients presenting with neurological symptoms, using a 1.5-Tesla MRI system (e.g., Philips Achieva, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Major antifungal-related adverse events, including nephrotoxicity, electrolyte disturbances, and hepatotoxicity, were retrospectively identified through a systematic review of medical records, laboratory results, and treatment notes documented during hospitalization.

Validity and Reliability

To promote data quality, several steps were implemented. The case report form was piloted on a small subset of records before full data extraction, which allowed refinement of variable definitions and coding rules. For imaging related variables, a random subset of CT scans was independently assessed by two otorhinolaryngologists who were blinded to clinical outcomes. Interobserver agreement for key radiologic features (such as orbital involvement and bony erosion) was quantified using simple consistency ratios and weighted kappa (κ) statistics. Measurement reliability for continuous variables (for example, age, duration of symptoms) was checked through repeated entry of a sample of cases and calculation of variation coefficients (CV%). These procedures were designed to minimize misclassification and improve internal validity, although residual information bias cannot be completely excluded in a retrospective design.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum values, coefficient of variation (CV%) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) when appropriate. Categorical variables were described as counts and percentages.

The distribution of continuous variables was examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to assess conformity to normality. Depending on the outcome of these tests, parametric or non-parametric methods were applied as appropriate. For comparisons of categorical variables between groups, Pearson chi square (χ2) tests were used when expected cell counts were adequate; Yates corrected chi square tests or Fisher exact tests were employed in situations with small cell frequencies. Relationships between continuous variables, or between continuous and ordinal variables, were evaluated using Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses, selected according to the distributional properties of the data.

Survival outcomes were assessed using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Group comparisons of survival curves were conducted using the log-rank test, and corresponding p-values are reported in the Results section and figure legends. Survival curves were generated for relevant subgroups, such as categories of comorbidity or treatment modality, and period specific mortality rates were calculated. Where feasible, differences between survival curves were explored using the log rank test. All statistical tests were two sided, and a p value of 0.05 or less was considered indicative of statistical significance. Given the observational nature of the study, findings are interpreted with caution, and emphasis is placed on effect sizes and confidence intervals rather than on p values alone.

Ethics and Approvals

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee of Dicle University Faculty of Medicine prior to data collection. Because this study was retrospective and based exclusively on the review of existing clinical records, the requirement for individual informed consent was formally waived by the ethics committee. All data were anonymized prior to analysis, and patient confidentiality was maintained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable institutional and international guidelines. Since the analysis was retrospective and based on existing clinical records, individual informed consent was waived in accordance with national and institutional regulations. Patient confidentiality was protected by anonymizing all data before analysis and storing the dataset on password protected computers accessible only to the research team.

4. Discussion

This 14-year, single-center series highlights the substantial clinical burden of mucormycosis in an ENT setting serving a population with a high prevalence of diabetes and other chronic comorbidities. Most patients in our cohort were middle-aged or older, and approximately three-quarters had at least one major comorbidity—findings that align with large-scale epidemiological reviews [

13]. However, our data indicate that the anatomical extent of disease at presentation, and the feasibility of combined therapy, may have a greater impact on survival than the presence of comorbid conditions alone. Survival exceeded 80% among patients with isolated sinonasal mucormycosis, declined to approximately 60% in those with rhino-orbital disease, and fell below 30% in cases with rhino-orbito-cerebral involvement. This gradient reflects prior ENT-based studies identifying intracranial extension as a critical prognostic turning point [

14].

Our findings also support the widely held view that combined surgical and systemic antifungal treatment is associated with improved survival compared to medical therapy alone. Surgical debridement remains a cornerstone of mucormycosis management; however, in cases with cerebral or skull base involvement, the optimal extent of surgery remains debated. In our practice, surgical aggressiveness was balanced against procedural risk. Rather than pursuing radical skull base resections based solely on radiological findings, we adopted a conservative but adequate debridement approach guided by visible necrosis and multidisciplinary assessment. This strategy aimed to achieve infection control while minimizing serious complications, such as cerebrospinal fluid leakage or meningoencephalocele. Patients who received debridement alongside amphotericin-based therapy had significantly higher survival than those treated with antifungals alone. Although selection bias is likely—since patients ineligible for surgery often have more extensive disease or are medically unstable—the direction and magnitude of the observed survival benefit align with observational data and guideline recommendations that emphasize early and repeated debridement when feasible [

5,

9,

10]. Our findings reinforce the clinical principle that timely surgical source control should be pursued aggressively in ENT practice, with operative decisions guided by comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation.

Interestingly, diabetes mellitus, while the most common comorbidity in our cohort, was not an independent predictor of mortality. This may appear counterintuitive, given extensive experimental and clinical data linking diabetes—particularly with ketoacidosis—to increased susceptibility to mucormycosis [

1,

6]. However, once infection is established, disease progression may be more strongly influenced by factors such as the degree of angioinvasion, timing of diagnosis, and capacity to perform radical debridement. Several authors have proposed that comorbidities serve primarily as “entry points” for infection, whereas short-term prognosis is dictated by anatomical stage and treatment adequacy [

9]. Our data support this concept, suggesting that even in diabetic patients, survival can be favorable when the disease is anatomically limited and managed with early surgical and antifungal intervention.

Comparisons with other ENT-focused series provide additional context. Gupta et al. reported a mortality rate of approximately 25% among 80 patients with ROCM, over half of whom had orbital involvement and 20% with intracranial extension [

3]. Similarly, Deb et al. described a cohort of 52 patients with high rates of hyperglycemia and steroid use, and widespread orbital or cerebral involvement [

14]. Studies from Turkey and neighboring regions, including case series and case reports, have likewise emphasized the predominance of diabetic patients and the frequent need for extensive surgery, including orbital exenteration and skull base resection in advanced cases [

15]. Our survival rates for sinonasal and rhino-orbital disease are broadly consistent with these publications. However, outcomes for rhino-orbito-cerebral cases were somewhat poorer in our cohort, which may reflect delayed presentation or limited neurosurgical access.

The surge in COVID-19-associated mucormycosis provides an additional framework for interpreting our findings. Case series from India consistently report high rates of ROCM in patients with recent SARS-CoV-2 infection, prior steroid use, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia, with mortality rates of 30–40% despite amphotericin therapy and extensive surgery [

16]. Although our study spans a longer timeframe and is not limited to COVID-related cases, overall mortality (~40%) and the prevalence of diabetes are similar. However, the higher proportion of isolated sinonasal disease in our sample may suggest that outside of epidemic contexts—with associated resource constraints and diagnostic delays—earlier detection is more achievable, particularly in specialized ENT centers.

Our findings also relate to ongoing debates on the optimal extent of surgery and the role of adjunctive antifungal agents. The strong association between intracranial extension and mortality in our cohort is consistent with the literature identifying cerebral involvement as the most ominous prognostic factor in ROCM [

11]. Despite aggressive debridement and systemic therapy, survival in these patients remained poor. Some authors advocate early orbital exenteration when there is fixed ophthalmoplegia or no light perception, while others recommend a more conservative, globe-sparing approach guided by clinical status and radiological findings [

3,

14]. Our dataset is too small to resolve this controversy; however, the high mortality among patients with brain involvement highlights the need for improved strategies in early staging and risk stratification.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, comparisons between treatment modalities are subject to confounding by indication. Patients treated with antifungal therapy alone often represent a higher-risk group with more extensive disease, poor surgical candidacy, or patient refusal, potentially inflating the observed benefit of combination therapy. Second, the retrospective design limited our ability to precisely reconstruct key time intervals (e.g., symptom onset to diagnosis, diagnosis to antifungal initiation or surgery). As a result, time-dependent effects could not be modeled. Heterogeneity in imaging protocols—particularly the selective use of contrast-enhanced CT or MRI—may have limited the detection of intracranial involvement, potentially leading to underestimation. Third, the small number of pediatric patients precluded age-stratified analyses, though descriptive comparisons suggest that the direction of associations was broadly consistent across age groups. Finally, adverse event monitoring relied on retrospective chart review and may have underestimated the true incidence of treatment-related toxicity.

Despite these limitations, the study has several strengths. It presents a relatively large ENT-focused cohort with histopathological confirmation over a long period, encompassing both pre- and post-COVID eras. It integrates clinical characteristics, imaging findings, treatment strategies, and survival outcomes into a single analysis—a relatively uncommon feature in the mucormycosis literature. Moreover, our findings are broadly consistent with global data and current guideline recommendations, supporting their external validity [

9,

17].

Clinically, three practical messages emerge for ENT teams. First, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for mucormycosis in patients with risk factors such as poorly controlled diabetes, recent steroid exposure, or immunosuppression, especially if they present with sinus or orbital symptoms. Second, rapid diagnosis and early initiation of amphotericin-based therapy, accompanied by timely debridement, remain central to improving outcomes. Third, anatomical staging using early CT and MRI is critical to guide surgical planning and prognostication. Future research should aim to build upon these findings through prospective, multicenter registries incorporating time-to-treatment metrics, functional outcomes, and quality of life measures. Such efforts will be crucial for developing refined, stage-based treatment algorithms that balance aggressive disease control with organ preservation.