Menstrual Cycle-Related Hormonal Fluctuations in ADHD: Effect on Cognitive Functioning—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

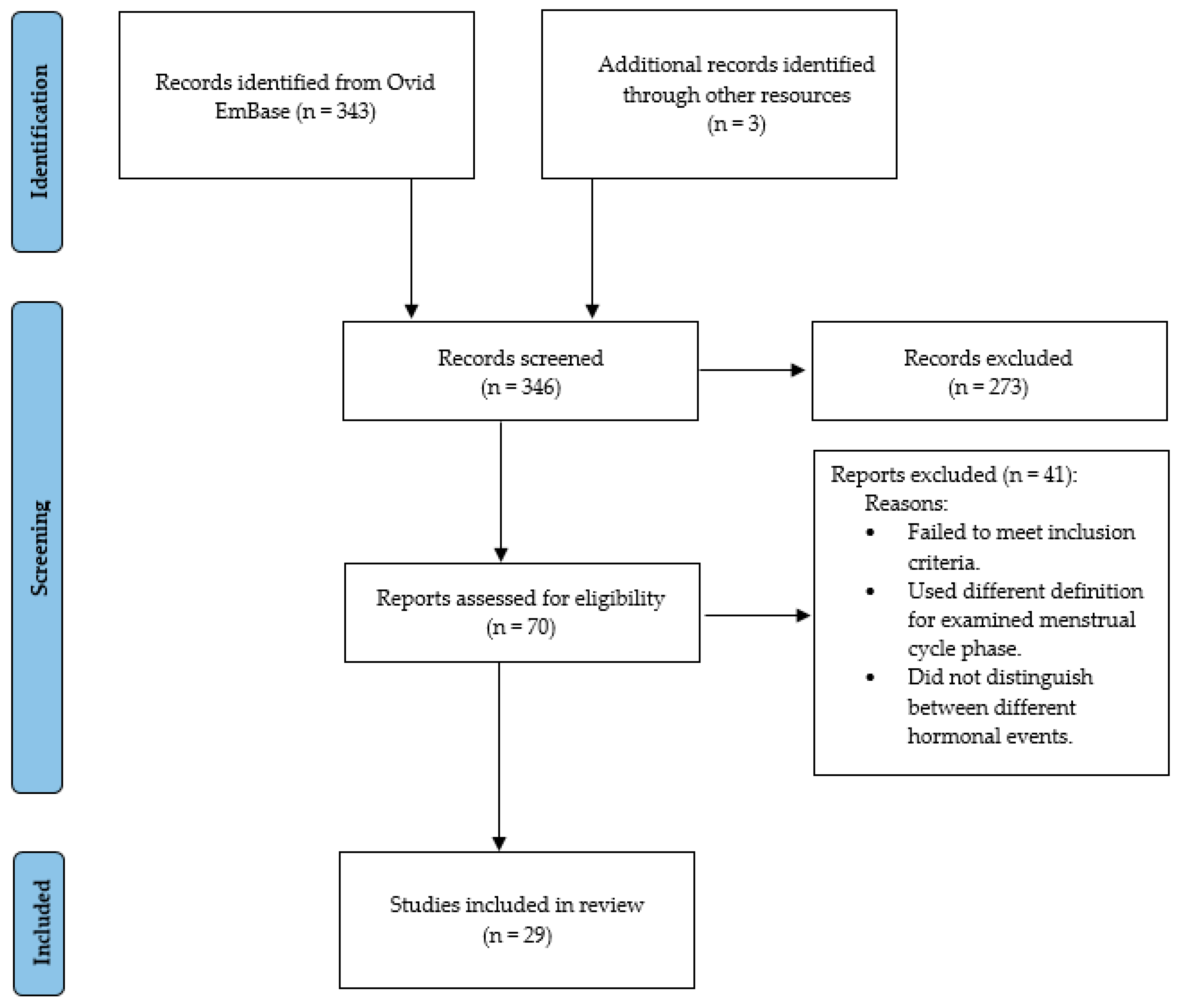

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Attention

- Seven were non-clinical investigations which reported improved or faster attentional performance during mid-luteal phases;

- Two studies that examined divided attention showed mixed results;

- Two studies reported impaired sustained attention during elevated oestrogen periods;

- Four studies examining clinical samples, including PMS and PMDD, identified attentional decline or increased variability during the mid-luteal or pre-menstrual phase.

3.2. Executive Function

- Four reported enhanced or more stable performance during the mid-luteal phase in non-clinical samples;

- Two studies identified performance decline during the pre-menstrual phase in women with PMS or PMDD.

Working Memory

- Four studies found no significant changes across menstrual cycle phases;

- Two studies observed contrasting effects of task-difficulty on working memory performance across the menstrual cycle;

- Three studies examining working memory found significant changes related to target detection during the mid-luteal phase;

- One study reported a perimenstrual decline in women with suicidal ideation, which was prevented with transdermal oestrogen administration.

3.3. Inhibition and Impulsivity

- Out of 4 studies that examined inhibition across the menstrual cycle, 3 studies in non-clinical samples reported no cycle-related differences, and only 1 study found an impaired response inhibition during the post-ovulatory and pre-menstrual phase in women with PMDD.

- All 5 studies in non-clinical women and women with PMDD that assessed objective or subjective impulsivity found that it increased around either ovulation or menstruation.

- One neuroimaging study in a non-clinical sample showed that right dlPFC activity was elevated during the mid-luteal phase and was sensitive to oestrogen levels.

3.4. ADHD Symptoms

- One study in a non-clinical sample found that ADHD symptoms exacerbated when oestrogen levels were low and progesterone levels were high, especially in those with high-trait impulsivity.

- Another study observed that women with both PMDD and ADHD reported more memory problems and dysfunctional impulsivity during the pre-ovulatory and mid-luteal phases compared to women with PMDD alone.

- Two qualitative studies reported that women with ADHD experienced worsening ADHD and depressive symptoms during the mid-luteal and (pre-)menstrual phase, and a decrease in stimulant medication effectiveness.

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognitive Function Across the Menstrual Cycle in ADHD

4.2. Cognitive Function Across the Menstrual Cycle in Relation to Mood

4.3. Cognitive Function Across the Menstrual Cycle in the General Population

4.4. Limitations and Future Considerations

4.5. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

- Within-subject, multi-cycle prospective designs;

- Standardised cognitive and hormonal measurement methods;

- Carefully monitored trials evaluating tailored medication strategies.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinshaw, S.P.; Nguyen, P.T.; O’Grady, S.M.; Rosenthal, E.A. Annual Research Review: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Girls and Women: Underrepresentation, Longitudinal Processes, and Key Directions. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 63, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowlem, F.D.; Rosenqvist, M.A.; Martin, J.; Lichtenstein, P.; Asherson, P.; Larsson, H. Sex Differences in Predicting ADHD Clinical Diagnosis and Pharmacological Treatment. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussbaum, N.L. ADHD and Female Specific Concerns: A Review of the Literature and Clinical Implications. J. Atten. Disord. 2012, 16, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, C.; Sundström Poromaa, I.; Leksell, D.; Ekholm Selling, K.; Cars, T.; Giacobini, M.; Young, S.; Kopp Kallner, H. Time after Time: Failure to Identify and Support Females with ADHD—A Swedish Population Register Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 65, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.; Johnston, C. Gender Differences in Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Narrative Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 40, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubia, K. Cognitive Neuroscience of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Its Clinical Translation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnin, E.; Maurs, C. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder during Adulthood. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 173, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pievsky, M.A.; McGrath, R.E. The Neurocognitive Profile of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review of Meta-Analyses. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2018, 33, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, J.J.S.; de Jong, M.; Agnew-Blais, J.; Amoretti, S.; Bang Madsen, K.; Barclay, I.; Bölte, S.; Borg Skoglund, C.; Broughton, T.; Carucci, S.; et al. Research Advances and Future Directions in Female ADHD: The Lifelong Interplay of Hormonal Fluctuations with Mood, Cognition, and Disease. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2025, 6, 1613628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, E.; Arbula, S.; Rossato, C.; Pacella, V.; Vallesi, A. Neuro-Cognitive Architecture of Executive Functions: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cortex 2019, 119, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuki, F.; Constantinidis, C. Bottom-up and Top-down Attention: Different Processes and Overlapping Neural Systems. Neuroscientist 2014, 20, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.E.; Posner, M.I. The Attention System of the Human Brain: 20 Years After. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A. Working Memory: Theories, Models, and Controversies. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Campo, N.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Sahakian, B.J.; Robbins, T.W. The Roles of Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, e145–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, T.R.; Monegro, A.; Nene, Y.; Fayyaz, M.; Bollu, P.C. Neurobiology of ADHD: A Review. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2019, 6, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wang, G.J.; Kollins, S.H.; Wigal, T.L.; Newcorn, J.H.; Telang, F.; Fowler, J.S.; Zhu, W.; Logan, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Evaluating Dopamine Reward Pathway in ADHD: Clinical Implications. JAMA 2009, 302, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, C.; Villringer, A.; Sacher, J. Sex Hormones Affect Neurotransmitters and Shape the Adult Female Brain during Hormonal Transition Periods. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

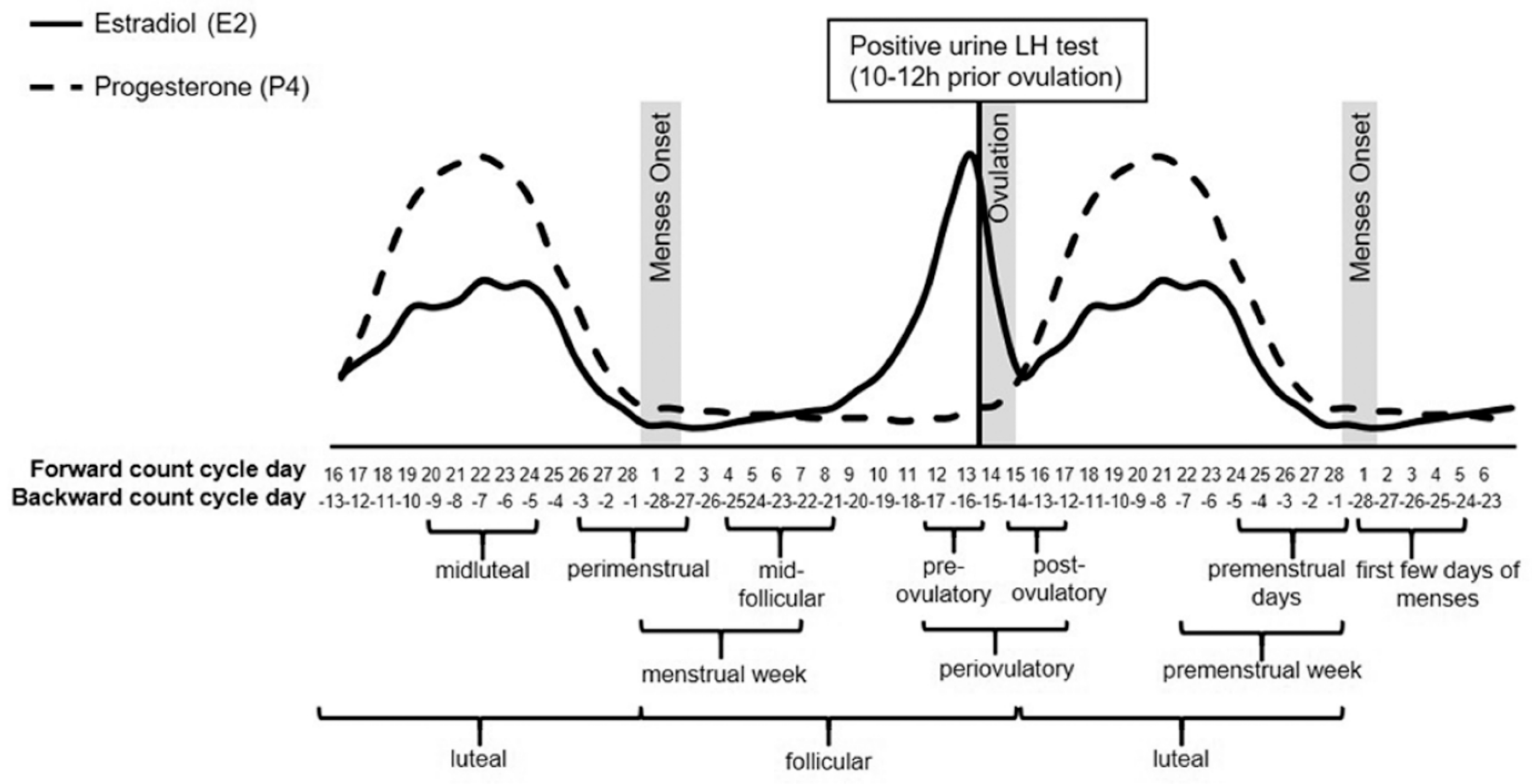

- Schmalenberger, K.M.; Tauseef, H.A.; Barone, J.C.; Owens, S.A.; Lieberman, L.; Jarczok, M.N.; Girdler, S.S.; Kiesner, J.; Ditzen, B.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A. How to Study the Menstrual Cycle: Practical Tools and Recommendations. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 123, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, A.G.; Nirjar, U.; Elkins, A.R.; Sizemore, Y.J.; Monticello, K.N.; Petersen, M.K.; Miller, S.A.; Barone, J.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A.; Martel, M.M. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and the Menstrual Cycle: Theory and Evidence. Horm. Behav. 2024, 158, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimov-Kochman, R.; Berger, I. Cognitive Functions of Regularly Cycling Women May Differ throughout the Month, Depending on Sex Hormone Status; a Possible Explanation to Conflicting Results of Studies of ADHD in Females. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 00191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, F.M.; Groen, Y.; Fuermaier, A.B.M.; Tucha, O. The Female Side of Pharmacotherapy for ADHD-A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 0239257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, J.; Thomas, N.; Gurvich, C. Cognition, the Menstrual Cycle, and Premenstrual Disorders: A Review. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorani, F.; Bijlenga, D.; Beekman, A.T.F.; van Someren, E.J.W.; Kooij, J.J.S. Prevalence of Hormone-Related Mood Disorder Symptoms in Women with ADHD. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 133, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, A.L. Women’s Health Equity: Call for Research on ADHD in Females. Available online: https://www.additudemag.com/health-equity-adhd-in-women-research/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A Scoping Review on the Conduct and Reporting of Scoping Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Z.Z.; Gotlieb, N.; Erez, O.; Wiznitzer, A.; Arbel, O.; Matas, D.; Koren, L.; Henik, A. Attentional Networks during the Menstrual Cycle. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 425, 113817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarczyk, J.; Schwertner, E.; Woloszyn, K.; Kuniecki, M. Phase of the Menstrual Cycle Affects Engagement of Attention with Emotional Images. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 104, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotzner, C.P.; Klimesch, W.; Kerschbaum, H.H. Progesterone-Associated Increase in ERP Amplitude Correlates with an Improvement in Performance in a Spatial Attention Paradigm. Brain Res. 2015, 1595, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Deng, S.W. Social Attention, Memory, and Memory-Guided Orienting Change across the Menstrual Cycle. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 251, 113808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkanat, M.; Özdemir Alkanat, H.; Akgün, E. Effects of Menstrual Cycle on Divided Attention in Dual-Task Performance. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 2021, 38, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, A. High Progesterone Levels Facilitate Women’s Social Information Processing by Optimizing Attention Allocation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 122, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Chen, D.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.Z. The Cycling Brain in the Workplace: Does Workload Modulate the Menstrual Cycle Effect on Cognition? Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 856276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pletzer, B.; Harris, T.A.; Ortner, T. Sex and Menstrual Cycle Influences on Three Aspects of Attention. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 179, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronca, F.; Blodgett, J.M.; Bruinvels, G.; Lowery, M.; Raviraj, M.; Sandhar, G.; Symeonides, N.; Jones, C.; Loosemore, M.; Burgess, P.W. Attentional, Anticipatory and Spatial Cognition Fluctuate throughout the Menstrual Cycle: Potential Implications for Female Sport. Neuropsychologia 2025, 206, 108909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, B.L.; Weymar, M.; Wendt, J. Premenstrual Syndrome Is Associated with Differences in Heart Rate Variability and Attentional Control throughout the Menstrual Cycle: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2024, 204, 112374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y. Early and Late Luteal Executive Function, Cognitive and Somatic Symptoms, and Emotional Regulation of Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Long, C.Y.; Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y. Comorbid Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. J. Women’s Health 2024, 33, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.Y.; Lin, P.C.; Hsu, C.J.; Lin, C.; Chen, I.J.; Ko, C.H. Attention, Response Inhibition, Impulsivity, and Decision-Making within Luteal Phase in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2023, 26, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Lopez, E.; Pletzer, B. Interactive Effects of Dopamine Baseline Levels and Cycle Phase on Executive Functions: The Role of Progesterone. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 00403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.X.; Fu, L.; Lei, Q.; Zhuang, J.Y. Ovarian Hormone Effects on Cognitive Flexibility in Social Contexts: Evidence from Resting-State and Task-Based FMRI. Physiol. Behav. 2025, 292, 114842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggert, L.; Kleinstäuber, M.; Hiller, W.; Witthöft, M. Emotional Interference and Attentional Processing in Premenstrual Syndrome. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaizauskaite, R.; Gladutyte, L.; Zelionkaite, I.; Griksiene, R. Exploring the Role of Sex, Sex Steroids, Menstrual Cycle, and Hormonal Contraception Use in Visual Working Memory: Insights from Behavioral and EEG Analyses. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2025, 209, 112520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Lopez, E.; Pletzer, B. Fronto-Striatal Changes along the Menstrual Cycle during Working Memory: Effect of Sex Hormones on Activation and Connectivity Patterns. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 125, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeners, B.; Kruger, T.H.C.; Geraedts, K.; Tronci, E.; Mancini, T.; Ille, F.; Egli, M.; Röblitz, S.; Saleh, L.; Spanaus, K.; et al. Lack of Associations between Female Hormone Levels and Visuospatial Working Memory, Divided Attention and Cognitive Bias across Two Consecutive Menstrual Cycles. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 00120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, C.C.; Jacobs, E.; D’Esposito, M.; Moser, J. Estradiol and the Catechol-o-Methyltransferase Gene Interact to Predict Working Memory Performance: A Replication and Extension. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2023, 35, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalenberger, K.M.; Mulligan, E.M.; Barone, J.C.; Nagpal, A.; Divine, M.M.; Maki, P.M.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A. Effects of Acute Estradiol Administration on Perimenstrual Worsening of Working Memory, Verbal Fluency, and Inhibition in Patients with Suicidal Ideation: A Randomized, Crossover Clinical Trial. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 342, 116188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsyan, K.K.; Manna, S.; Ahluwalia, H. Effects of Menstrual Cycle on Working Memory and Its Correlation with Menstrual Distress Score: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2023, 17, CC01–CC05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulsyan, K.K.; Manna, S.; Ahluwalia, H. Change in Auditory and Visuospatial Working Memory with Phases of Menstrual Cycle: A Prospective Study of Three Consecutive Cycles. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2025, 32, 1394–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürger, I.; Erlandsson, K.; Borneskog, C. Perceived Associations between the Menstrual Cycle and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Qualitative Interview Study Exploring Lived Experiences. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2024, 40, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Wynchank, D.S.M.R.; van Andel, E.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Kooij, J.J.S. Female-Specific Pharmacotherapy in ADHD: Premenstrual Adjustment of Psychostimulant Dosage. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1306194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekhof, E.K. Be Quick about It. Endogenous Estradiol Level, Menstrual Cycle Phase and Trait Impulsiveness Predict Impulsive Choice in the Context of Reward Acquisition. Horm. Behav. 2015, 74, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pletzer, B.; Harris, T.A.; Scheuringer, A.; Hidalgo-Lopez, E. The Cycling Brain: Menstrual Cycle Related Fluctuations in Hippocampal and Fronto-Striatal Activation and Connectivity during Cognitive Tasks. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.; Martel, M.M. Reproductive Steroids and ADHD Symptoms across the Menstrual Cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 88, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.Y.; Wang, J.X.; Lei, Q.; Zhang, W.; Fan, M. Neural Basis of Increased Cognitive Control of Impulsivity During the Mid-Luteal Phase Relative to the Late Follicular Phase of the Menstrual Cycle. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 568399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, W.J.; Lee, T.Y.; Kim, N.S.; Kwon, J.S. The Role of Estrogen Receptors and Their Signaling across Psychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoest, K.E.; Cummings, J.A.; Becker, J.B. Estradiol, Dopamine and Motivation. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2014, 14, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E.; D’Esposito, M. Estrogen Shapes Dopamine-Dependent Cognitive Processes: Implications for Women’s Health. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 5286–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, M.B.; Wankhede, N.L.; Goyanka, B.K.; Gupta, R.; Bishoyi, A.K.; Nathiya, D.; Kaur, P.; Shanno, K.; Taksande, B.G.; Khalid, M.; et al. Unveiling the Neurotransmitter Symphony: Dynamic Shifts in Neurotransmitter Levels during Menstruation. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, P.A.; Ezzat, W.H.; Ginsburg, K.; Moore, G.J. Prefrontal Cortex as the Site of Estrogen’s Effect on Cognition. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001, 26, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubol, M.; Epperson, C.N.; Sacher, J.; Pletzer, B.; Derntl, B.; Lanzenberger, R.; Sundström-Poromaa, I.; Comasco, E. Neuroimaging the Menstrual Cycle: A Multimodal Systematic Review. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 60, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, T.; Nieder, A. Dopamine and Cognitive Control in Prefrontal Cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.R.; Schmalenberger, K.M.; Eng, A.G.; Stumper, A.; Martel, M.M.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.A. Dimensional Affective Sensitivity to Hormones across the Menstrual Cycle (DASH-MC): A Transdiagnostic Framework for Ovarian Steroid Influences on Psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 30, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malén, T.; Karjalainen, T.; Isojärvi, J.; Vehtari, A.; Bürkner, P.C.; Putkinen, V.; Kaasinen, V.; Hietala, J.; Nuutila, P.; Rinne, J.; et al. Atlas of Type 2 Dopamine Receptors in the Human Brain: Age and Sex Dependent Variability in a Large PET Cohort. Neuroimage 2022, 255, 119149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachry, J.E.; Nolan, S.O.; Brady, L.J.; Kelly, S.J.; Siciliano, C.A.; Calipari, E.S. Sex Differences in Dopamine Release Regulation in the Striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixo, M.; Johansson, M.; Timby, E.; Michalski, L.; Bäckström, T. Effects of GABA Active Steroids in the Female Brain with a Focus on the Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 30, e12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingen, G.A.; Van Broekhoven, F.; Verkes, R.J.; Petersson, K.M.; Bäckström, T.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Fernández, G. Progesterone Selectively Increases Amygdala Reactivity in Women. Mol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäckström, T.; Bixo, M.; Johansson, M.; Nyberg, S.; Ossewaarde, L.; Ragagnin, G.; Savic, I.; Strömberg, J.; Timby, E.; van Broekhoven, F.; et al. Allopregnanolone and Mood Disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 113, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantsoo, L.; Epperson, C.N. Allopregnanolone in Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): Evidence for Dysregulated Sensitivity to GABA-A Receptor Modulating Neuroactive Steroids across the Menstrual Cycle. Neurobiol. Stress 2020, 12, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.; Mandal, N.; Sinha, V.K. Change of Symptoms of Schizophrenia across Phases of Menstrual Cycle. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2020, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endicott, J.; Nee, J.; Harrison, W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP): Reliability and Validity. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2005, 9, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynchank, D.; De Jong, M.; Kooij, S.J.; Wynchank, D.S.M.R. Practical Tools for Female-Specific ADHD: The Impact of Hormonal Fluctuations in Clinical Practice and from the Literature. Eur. Psychiatry 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Zhang, J.; Elfenbein, H.A. Menstrual Cycle Effects on Cognitive Performance: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.G.V.; Ramos, M.G.; Hara, C.; Stumpf, B.P.; Rocha, F.L. Neuropsychological Performance and Menstrual Cycle: A Literature Review. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2012, 34, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, G.; Frazier, J.A.; Rauch, S.L.; Seidman, L.J.; Whalen, P.J.; Jenike, M.A.; Rosen, B.R.; Biederman, J. Anterior Cingulate Cortex Dysfunction in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Revealed by FMRI and the Counting Stroop. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 45, 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, G. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Attention Networks. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevarra, D.A.; Louis, C.C.; Gloe, L.M.; Block, S.R.; Kashy, D.A.; Klump, K.L.; Moser, J.S. Examining a Window of Vulnerability for Affective Symptoms in the Mid-Luteal Phase of the Menstrual Cycle. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 147, 105958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.A.; Makhanova, A.; Marcinkowska, U.M.; Jasienska, G.; McNulty, J.K.; Eckel, L.A.; Nikonova, L.; Maner, J.K. Progesterone and Women’s Anxiety across the Menstrual Cycle. Horm. Behav. 2018, 102, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, N.; London, E.D.; Liang, L.; Ghahremani, D.G.; Gerards, R.; Goldman, L.; Rapkin, A.J. Emotion Regulation in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggert, L.; Witthoft, M.; Hiller, W.; Kleinstauber, M. Emotion Regulation in Women with Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS): Explicit and Implicit Assessments. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2016, 40, 747–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Wynchank, D.S.M.R.; Michielsen, M.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Kooij, J.J.S. A Female-Specific Treatment Group for ADHD-Description of the Programme and Qualitative Analysis of First Experiences. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Subjects | Measured Domains (Instrument) | Menstrual Cycle Phases | Phase Verification Method | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen et al. (2022) [26] | NCF = 21 OCF = 24 | Attention (Attentional network test—interactions with alerting and no-alerting condition) | Mid-follicular Mid-luteal | Saliva samples | No significant differences between phases in attention in OCF group Mid-luteal phase: ↑Alertness mediated by P4 in NCF group, ↑Interference in incongruent trials |

| Pilarczyk et al. (2019) [27] | NCF = 20 | Attention allocation to different stimuli (eye-tracking) | Mid-follicular Mid-luteal | Saliva samples Ovulation test | Mid-luteal phase: Faster RT, attention was allocated earlier to key regions of presented stimuli P4 levels did not correlate significantly with any measure of visual attention. |

| Brotzner et al. (2015) [28] | NCF = 18 | Spatial attention (Visuospatial cued attention task) | Mid-follicular Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Saliva samples Ovulation test | Mid-luteal phase: ↑Attention, RT correlated positively to P4 levels |

| Li and Deng (2022) [29] | NCF = 36 | Social cognition (visual search task with social and object distractors) Attention (eye-tracking) | Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Backwards counting a | Pre-ovulatory phase: Slower RT, ↓Fixation on social distractors Mid-luteal phase: Faster RT, ↑Fixation social distractors |

| Alkanat et al. (2021) [30] | NCF = 40 | Divided attention (Annett’s peg moving task + Go/no-go task) | Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Ovulation test | Mid-luteal phase: ↑Divided attention |

| Wang and Chen (2020) [31] | NCF = 26 | Attention (Attention network test) Emotional information processing (Emotional face flanker task) | Menstrual Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal Pre-menstrual | Self-report tracking b Saliva samples | Mid-luteal phase: Slower RT, ↑Accuracy RT to sad faces correlated positively with P4 levels |

| Xu et al. (2022) [32] | NCF = 79 | Cognitive flexibility (Task-switching paradigm) Divided attention (Audiovisual cross-modal monitoring task) Inhibition (spatial Stroop task) Working memory (Multiple change detection paradigm) | Menstrual Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Backwards counting a | Mid-luteal: ↑Sensitivity on divided attention task, ↑Cognitive flexibility |

| Pletzer et al. (2017) [33] | Males = 35 NCF = 32 | Selective, divided and sustained attention (d2-R, FAIR-2, sustained attention test from the Wiener Test system) | Mid-follicular Mid-luteal | Backwards counting b Ovulation test | Mid-luteal phase: ↓Selective/divided attention, ↓Sustained attention in NCF |

| Ronca et al. (2025) [34] | Males = 96 NCF = 105 OCF = 47 | Sustained attention, inhibition (Smiley task battery) Reaction time (Spatial simple reaction time) Visuospatial function (Cube Analysis test) Mood (Burgess Brief Mood Questionnaire) | Menstrual Mid-follicular Pre-ovulatory Luteal | Self-report tracking a Backwards counting a | Menstrual phase: ↑Cognitive performance, faster RT, ↓Mood in NCF Pre-ovulatory phase: ↓Sustained attention in NCF |

| Blaser et al. (2024) [35] | Low PMS = 36 High PMS = 29 | Attention (Attentional network test-R with emotional stimuli) | Mid-follicular Mid-luteal Pre-menstrual | Forward and backwards counting a | Mid-luteal phase: ↓Attentional control in high PMS |

| Lin et al. (2022) [36] | PMDD = 63 NCF = 53 | Executive function (Simon Task) Attention (Attention and Performance Self-Assessment scale) Fatigue (Fatigue Severity Scale) Insomnia (Pittsburgh Insomnia Rating Scale) Depression (The Center for Epidemiological Studies’ Depression Scale) Emotion regulation (Emotion Regulation Questionnaire) | Mid-luteal Pre-menstrual | Self-report tracking a | Mid-luteal: ↓Cognitive reappraisal of emotions in PMDD Pre-menstrual: ↓Executive function, ↓Attention, ↓Cognitive reappraisal of emotions, ↑Insomnia, ↑Fatigue in PMDD Inattention was the most associated factor of PMDD functional impairment |

| Lin et al. (2024) [37] | PMDD = 58 No PMDD = 50 | ADHD symptoms (psychiatric assessment) Attention (Attention and Performance Self-Assessment scale) Impulsivity (Dickman Impulsivity Inventory) | Pre-menstrual Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Self-report tracking b Ovulation test | Diagnostic criteria for ADHD were met significantly more often in PMDD group Pre-menstrual phase: ↓Attention, ↑Impulsivity in PMDD only Pre-ovulatory phase: ↓Attention, ↑Impulsivity in PMDD (with ADHD) Mid-luteal phase: ↓Attention |

| Yen et al. (2023) [38] | PMDD = 63 No PMDD = 53 | Inhibition (Go/no-go task) Attention (Go trials in Go/no-go task) Impulsivity (Dickman’s Impulsivity Inventory) | Post-ovulatory Pre-menstrual | Self-report tracking a | Post-ovulatory phase: ↓Inhibition, ↑Impulsivity in PMDD Pre-menstrual phase: ↓Inhibition, ↓Attention, ↑Impulsivity in PMDD |

| Hidalgo-Lopez and Pletzer (2017) [39] | NCF = 36 | WM (n-back test) Executive function (Stroop task) | Menstrual Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Saliva samples | Mid-luteal phase: ↑WM when ↑P4, faster RT on Stroop-task when ↑P4, ↑Baseline DA was related to ↓Inhibition, ↓Eyeblink-rate was related to ↑Inhibition |

| Wang et al. (2025) [40] | Pre-ovulatory = 28 Mid-luteal = 25 | Executive function (face-gender Stroop task) Resting-state fMRI Task-based fMRI | Pre-menstrual Mid-luteal | Self-report tracking b Saliva samples | Mid-luteal phase: ↑Accuracy for female face stimuli only P4 was positively correlated to differences in RT to female and male faces, and the nodal efficiency of inferior frontal gyrus in the resting-state executive control network |

| Eggert et al. (2017) [41] | PMS = 55 Non-PMS = 55 | Executive Function (Emotional Stroop task) | Mid-follicular Pre-menstrual | Self-report tracking a | Mid-follicular phase: ↑Emotional Stroop effect in non-PMS women Pre-menstrual phase: ↑Emotional Stroop effect in PMS women |

| Gaizauskaite et al. (2025) [42] | Males = 32 NCF = 133 OCF = 37 IUD = 28 | WM (Bilateral change detection task) | Mid-follicular Mid-luteal | Saliva samples | No systematic differences in WM between groups nor any correlations with hormone levels Mid-follicular phase: ↓WM with increasing task difficulty |

| Hidalgo-Lopez and Pletzer (2021) [43] | NCF = 39 | WM (n-back test) Executive function (n-back test) | Menstrual Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Saliva samples | No menstrual cycle effects were observed on behavioural measures Different patterns of brain connectivity, depending on menstrual cycle phase Menstrual phase: ↓Connectivity between fronto-striatal areas and regions related to salience and cognitive effort Pre-ovulatory: Negative connectivity between fronto-striatal areas and regions related to salience and cognitive effort Mid-luteal: ↑Connectivity between fronto-striatal areas, posteromedial structures, and regions related to salience and cognitive effort |

| Leeners et al. (2017) [44] | First cycle: NCF = 88, Second cycle: NCF = 68 | WM (block span test) Attention (Divided Attention Bimodal task) Cognitive control (Cognitive Bias test) | Pre-menstrual Mid-follicular Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Blood samples Transvaginal ultrasound | Mid-follicular phase: ↓Attention in first cycle only Pre-ovulatory phase: ↑Attention in first cycle only Mid-luteal: P4 negatively correlated to WM in first cycle only No findings replicated during the second menstrual cycle |

| Louis et al. (2023) [45] | Met/Met c NCF = 33 Val/Val c NCF = 41 | WM (n-back test) | Full menstrual cycle | Daily saliva samples | Val/Val*: when ↑E2, ↑WM (within-person) Met/Met*: when ↑E2, ↓WM (within-person) Within-person E2 levels were negatively correlated to RT |

| Schmalenberger et al. (2024) [46] | NCF = 19 (with suicidal ideation) | WM (n-back) Verbal fluency (Verbal fluency test) Inhibition (Stop-signal task) | Menstrual Mid-follicular Mid-luteal | Ovulation test E2 transdermal patch Placebo patch Placebo pill | (pre-)menstrual phase: ↓WM, ↓Verbal fluency in placebo condition E2 administration (regardless of additional P4) prevented decreased WM and verbal fluency performance during the (pre-)menstrual phase |

| Tuslyan et al. (2023a) [47] | NCF = 40 | WM (dual-task n-back test) | Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Self-report tracking a Backwards counting a | Mid-luteal phase: ↑WM |

| Tuslyan et al. (2023b) [48] | NCF = 40 | WM (dual-task n-back test) | Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Self-report tracking a Backwards counting a | Mid-luteal phase: ↑Target detection, performance remained stable No significant differences were found across 3 menstrual cycles |

| Bürger et al. (2024) [49] | NCF with ADHD = 10 | ADHD symptoms (interviews) | Full menstrual cycle | Self-report tracking a | Menstrual phase: ↑ADHD symptoms (Executive dysfunction, emotional dysregulation, inattention) Mid-luteal phase: ↑ADHD symptoms (Executive dysfunction, emotional dysregulation, inattention), ↓Effectiveness medication |

| De Jong et al. (2023) [50] | NCF with ADHD and co-occurring conditions = 9 | ADHD symptoms and pharmacotherapy (Community case study) | Pre-menstrual | Self-report tracking a | Pre-menstrual phase: ↑ADHD and depressive symptoms, ↓Effectiveness medication. Increasing the stimulant dosage during the premenstrual week improved ADHD and mood symptoms with minimal adverse events |

| Diekhof (2015) [51] | NCF = 28 (low trait impulsivity = 14) | Impulsivity (reward acquisition paradigm) Trait impulsivity (Barrett Impulsiveness Scale) | Menstrual Pre-ovulatory | Self-report tracking b Saliva samples | Menstrual phase: ↑Impulsive choices E2 levels correlated positively with impulsive choices during the menstrual phase, particularly in women with low trait impulsiveness |

| Pletzer et al. (2019) [52] | NCF = 36 | Spatial navigation (landmark test) Verbal fluency (verbal fluency test) | Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Saliva samples Ovulation test | No significant cognitive performance differences along the menstrual cycle. Pre-ovulatory phase: E2 boosts hippocampal activation Mid-luteal phase: P4 boosts fronto-striatal activation |

| Roberts et al. (2018) [53] | NCF = 32 | ADHD symptoms (Current ADHD Symptoms Scale: Self-report) Trait impulsivity (Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking-Positive Urgency Trait Impulsivity Scale) | Full menstrual cycle | Saliva samples (daily) | Post-ovulatory phase: ↑Inattention symptoms, ↑Hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms Mid-follicular phase: ↑Hyperactivity/impulsivity, especially with high trait impulsivity Decreased E2 + increased P4 (mid-luteal phase): ↑ADHD symptoms, especially with high trait impulsivity |

| Zhuang et al. (2020) [54] | NCF = 16 | Impulsivity (Monetary delay discounting task) Resting-state fMRI Task-based fMRI | Pre-ovulatory Mid-luteal | Backwards counting a | Pre-ovulatory phase: ↑Responsivity to short-term rewards, ↑Activity in dorsal striatum, dorsal striatum-dlPFC connectivity magnitude correlated negatively with impulsivity Mid-luteal phase: ↑DlPFC activity in rest, which was sensitive to E2 levels |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wynchank, D.; Sutrisno, R.M.G.T.M.F.; van Andel, E.; Kooij, J.J.S. Menstrual Cycle-Related Hormonal Fluctuations in ADHD: Effect on Cognitive Functioning—A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010121

Wynchank D, Sutrisno RMGTMF, van Andel E, Kooij JJS. Menstrual Cycle-Related Hormonal Fluctuations in ADHD: Effect on Cognitive Functioning—A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010121

Chicago/Turabian StyleWynchank, Dora, Regina M. G. T. M. F. Sutrisno, Emma van Andel, and J. J. Sandra Kooij. 2026. "Menstrual Cycle-Related Hormonal Fluctuations in ADHD: Effect on Cognitive Functioning—A Narrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010121

APA StyleWynchank, D., Sutrisno, R. M. G. T. M. F., van Andel, E., & Kooij, J. J. S. (2026). Menstrual Cycle-Related Hormonal Fluctuations in ADHD: Effect on Cognitive Functioning—A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010121