Optimising Pain Relief in Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

3. Opioids

4. Other Modalities

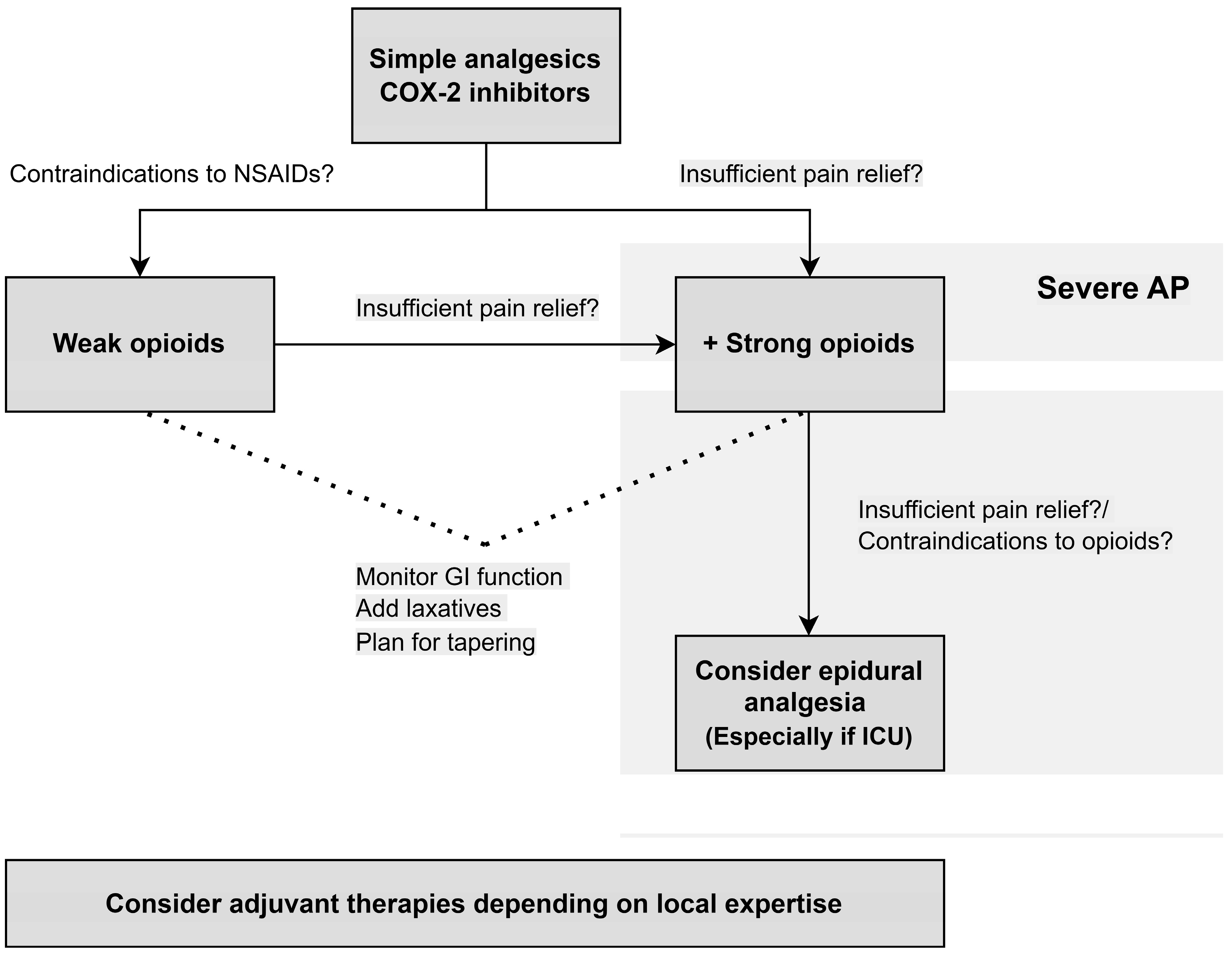

5. Treatment Algorithm

- COX-2 inhibitors decrease the risk of severe AP in patients with no contraindications to NSAIDs.

- Opioid-based therapies decrease the need for rescue analgesia.

- Opioids are safe for AP patients. Due to the risk of dependency, physicians should have a plan for tapering.

- Epidural analgesia is a safe alternative and may improve pain relief for patients with severe AP requiring admission to the intensive care unit or for patients with contraindications to opioid treatment.

- Adjuvant therapies, such as nerve blocks and acupuncture, should be considered in all patients depending on local expertise for add-on effect.

- In patients with severe AP, including organ failure, pain control should be prioritised and strong opioids, alternatively epidural analgesia, should be started upfront.

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Acute Pancreatitis |

| NSAIDs | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| VAS | Visual Analogous Scale |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| APACHE-II | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II |

References

- Banks, P.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Dervenis, C.; Gooszen, H.G.; Johnson, C.D.; Sarr, M.G.; Tsiotos, G.G.; Vege, S.S.; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, 62, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandanaboyana, S.; Siggaard Knoph, C.; Kuhlmann, L.; Forget, P.; Pogatzki-Zahn, E.; Huang, W.; Bonovas, S.; Piovani, D.; Scheers, I.; Cardenas Jean, K.; et al. Opioid analgesia and severity of acute pancreatitis: An international multicentre cohort study on pain management in acute pancreatitis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2024, 12, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoph, C.S.; Pandanaboyana, S.; Drewes, A.M.; Kuhlmann, L.; Joseph, N.; Windsor, J.; Olsen, S.S.; Varghese, C.; Huang, W.; Dhar, J.; et al. Pain intensity and prognosis of acute pancreatitis in an international, prospective study. Br. J. Surg. 2025, 112, znaf155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasanell, K.E.; Davis, B.; Lyons, J.; Chen, Z.; Lee, K.K.; Slivka, A.; Whitcomb, D.C. Pain in Chronic Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 36, 335–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, O.H.; Gerasimenko, J.V.; Gerasimenko, O.V.; Gryshchenko, O.; Peng, S. The roles of calcium and ATP in the physiology and pathology of the exocrine pancreas. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1691–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szatmary, P. Acute Pancreatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Drugs 2022, 82, 1251–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criddle, D.N. Reactive oxygen species, Ca2+ stores and acute pancreatitis; a step closer to therapy? Cell Calcium 2016, 60, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, M.D.; Bonkhoff, H.; Vollmar, B. Ischemia-reperfusion-induced pancreatic microvascular injury. An intravital fluorescence microscopic study in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1996, 41, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2013, 13, e1–e15. [CrossRef]

- De-Madaria, E.; Buxbaum, J.L.; Maisonneuve, P.; García García de Paredes, A.; Zapater, P.; Guilabert, L.; Vaillo-Rocamora, A.; Rodríguez-Gandía, M.Á.; Donate-Ortega, J.; Lozada-Hernández, E.E.; et al. Aggressive or Moderate Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Pancreatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Han, C.; Luo, R.; Cai, W.; Xia, Q.; Jiang, R.; Ferdek, P.E.; Liu, T.; Huang, W. Molecular mechanisms of pain in acute pancreatitis: Recent basic research advances and therapeutic implications. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1331438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceppa, E.P.; Lyo, V.; Grady, E.F.; Knecht, W.; Grahn, S.; Peterson, A.; Bunnett, N.W.; Kirkwood, K.S.; Cattaruzza, F. Serine proteases mediate inflammatory pain in acute pancreatitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 300, G1033–G1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, V.; Munnelly, S.; Grammatikopoulos, T.; Mole, D.; Hopper, A.; Ryan, B.; Phillips, M.; Tarpey, M.; Leeds, J. The top 10 research priorities for pancreatitis: Findings from a James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 780–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, P.E.; Raghavan, M. Stress-hyperglycemia, insulin and immunomodulation in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungqvist, O.; Nygren, J.; Soop, M.; Thorell, A. Metabolic perioperative management: Novel concepts. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2005, 11, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, B.A.; Faraday, N.; Campbell, D.; Dise, K.; Bell, W.; Goldschmidt, P. Hemostatic effects of stress hormone infusion. Anesthesiology 1994, 81, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilakopoulos, T.; Mastora, Z.; Katsaounou, P.; Doukas, G.; Klimopoulos, S.; Roussos, C.; Zakynthinos, S. Contribution of pain to inspiratory muscle dysfunction after upper abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 161, 1372–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaussier, M.; Genty, T.; Lescot, T.; Aissou, M. Influence of pain on postoperative ventilatory disturbances. Management and expected benefits. Ann. Franç. Anesth. Réanim. 2014, 33, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardeni, I.Z.; Shavit, Y.; Bessler, H.; Mayburd, E.; Grinevich, G.; Beilin, B. Comparison of postoperative pain management techniques on endocrine response to surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Surg. 2007, 5, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Morlion, B.; Perrot, S.; Dahan, A.; Dickenson, A.; Kress, H.G.G.; Wells, C.; Bouhassira, D.; Mohr Drewes, A. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenner, S.; Vege, S.S.; Sheth, S.G.; Sauer, B.; Yang, A.; Conwell, D.L.; Yadlapati, R.H.; Gardner, T.B. American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäniemi, A.; Tolonen, M.; Tarasconi, A.; Segovia-Lohse, H.; Gamberini, E.; Kirkpatrick, A.W.; Ball, C.G.; Parry, N.; Sartelli, M.; Wolbrink, D.; et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2019, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoe, M.; Takada, T.; Mayumi, T.; Yoshida, M.; Isaji, S.; Wada, K.; Itoi, T.; Sata, N.; Gabata, T.; Igarashi, H.; et al. Japanese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: Japanese Guidelines 2015. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2015, 22, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandanaboyana, S.; Siggaard Knoph, C.; Kuhlmann, L.; Forget, P.; Pogatzki-Zahn, E.; Huang, W.; Bonovas, S.; Piovani, D.; Scheers, I.; Cardenas Jean, K.; et al. European Interdisciplinary Guidelines on Pain Management in Acute Pancreatitis: UEG, EPC, EDS, ESDO, EAGEN, ESPGHAN, ESGAR, and ESPCG evidence-based recommendations Acute Pancreatitis Multidisciplinary Group. United European Gastroenterol. J. 2025, under review. [Google Scholar]

- Lankisch, P.G.; Apte, M.; Banks, P.A. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet 2015, 386, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventafridda, V.; Saita, L.; Ripamonti, C.; De Conno, F. WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. Int. J. Tissue React. 1985, 7, 93–96. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2409039 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Knoph, C.S.; Lucocq, J.; Kamarajah, S.K.; Olesen, S.S.; Jones, M.; Samanta, J.; Talukdar, R.; Capurso, G.; De-Madaria, E.; Yadav, D.; et al. Global trends in opioid use for pain management in acute pancreatitis: A multicentre prospective observational study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2024, 12, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbehøj, N.; Friis, J.; Svendsen, L.B.; Bülow, S.; Madsen, P. Indomethacin treatment of acute pancreatitis: A controlled double-blind trial. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1985, 20, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülen, B.; Dur, A.; Serinken, M.; Karcioğlu, Ö.; Sönmez, E. Pain treatment in patients with acute pancreatitis: A randomized controlled trial. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 27, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.S.; Muktesh, G.; Samra, T.; Sarma, P.; Samanta, J.; Sinha, S.K.; Dhaka, N.; Yadav, T.D.; Gupta, V.; Kochhar, R. Comparison of efficacy of diclofenac and tramadol in relieving pain in patients of acute pancreatitis: A randomized parallel group double blind active controlled pilot study. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, M.; Samanta, J.; Kumar, A.; Choudhury, A.; Dhar, J.; Jafra, A.; Chauhan, R.; Muktesh, G.; Gupta, P.; Gupta, V.; et al. Buprenorphine Versus Diclofenac for Pain Relief in Acute Pancreatitis: A Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 22, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.J.; Jain, S.; Bopanna, S.; Gupta, S.; Singh, P.; Trikha, A.; Sreenivas, V.; Garg, P.K. Pentazocine, a Kappa-Opioid AgonistIs Better Than Diclofenac for Analgesia in Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.; Dutta, P.; Hawa, F.; Quingalahua, E.; Marin, R.; Vilela, A.; Nix, T.; Mendoza-Ladd, A.; Wilcox, C.M.; Chalhoub, J.M.; et al. Effect of selective COX-2 inhibitors and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on severity of acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology 2025, 25, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurso, G.; Malesci, A. Targeting inflammation to prevent severe acute pancreatitis: NSAIDs are not the holy grail. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 1021–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machicado, J.D.; Mounzer, R.; Paragomi, P.; Pothoulakis, I.; Hart, P.A.; Conwell, D.L.; De-Madaria, E.; Greer, P.; Yadav, D.; Whitcomb, D.C.; et al. Rectal Indomethacin Does Not Mitigate the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome in Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized Trial. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2021, 12, e00415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatpanahi, Z.V.; Shahbazi, S.; Shahbazi, E. Ketorolac and Predicted Severe Acute Pancreatitis: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Med. Res. 2022, 20, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Ma, X.; Jia, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, M.; Wan, X.; Tang, C.; Huang, L. Prevention of Severe Acute Pancreatitis with Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Feng, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, R.; Peng, L.; He, M.; Tang, Y.; et al. Parecoxib sequential with imrecoxib for occurrence and remission of severe acute pancreatitis: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Gut 2025, 74, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.J.; Garg, P. Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Pathway: ‘Ice’ for Burning Pancreas? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1540–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Cai, W.; Kattakayam, A.; He, W.; Ke, L.; Szatmary, P.; Liu, T.; Singh, V.; Mukherjee, R.; Huang, W.; et al. Pharmacological trials of early intervention in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: Implications for therapeutic window and core outcome set. Gut 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.U.; Butler, R.K.; Chen, W. Factors Associated with Opioid Use in Patients Hospitalized for Acute Pancreatitis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, B.; Gougol, A.; Gao, X.; Reddy, N.; Talukdar, R.; Kochhar, R.; Goenka, M.K.; Gulla, A.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Singh, V.K.; et al. Worldwide Variations in Demographics, Management, and Outcomes of Acute Pancreatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1567–1575.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobs, R.; Adamek, M.U.; von Bubnoff, A.C.; Riemann, J.F. Buprenorphine or procaine for pain relief in acute pancreatitis. A prospective randomized study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 35, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Pross, M.; Schulz, H.U.; Schmidt, U.; Malfertheiner, P. Procaine hydrochloride fails to relieve pain in patients with acute pancreatitis. Digestion 2004, 69, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, A.M.; Martínez, J.; Martinez, E.; de Madaria, E.; Llorens, P.; Horga, J.F.; Pérez-Mateo, M. Efficacy and Tolerance of Metamizole versus Morphine for Acute Pancreatitis Pain. Pancreatology 2008, 8, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamey, S.L.; Finlay, I.G.; Carter, D.C.; Imrie, C.W. Analgesia in acute pancreatitis: Comparison of buprenorphine and pethidine. Br. Med. J. Clin. Res. Ed. 1984, 288, 1494–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Esler, R.; Asher, G. Transdermal fentanyl for the management of acute pancreatitis pain. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2002, 15, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jiang, K.; Liu, F.; Zhu, P.; Cai, F.; He, Y.; Jin, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, Q.; Hu, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenous hydromorphone patient-controlled analgesia versus intramuscular pethidine in acute pancreatitis: An open-label, randomized controlled trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 962671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ona, X.B.; Comas, D.R.; Urrútia, G. Opioids for acute pancreatitis pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 7, CD009179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Liu, F.; Wen, Y.; Han, C.; Prasad, M.; Xia, Q.; Singh, V.K.; Sutton, R.; Huang, W. Pain Management in Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 782151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, M.; Almulihi, Q.; Almumtin, H.; Alghanim, M.; AlAbdulbaqi, D.; Almulihi, F. The Efficacy and Safety of Using Opioids in Acute Pancreatitis: An Update on Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Arch. 2023, 77, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, C.; Bai, Z.; Zhou, W.; Yan, J.; Li, X. Parenteral analgesics for pain relief in acute pancreatitis: A. systematic review. Pancreatology 2013, 13, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrai, M.; Dawra, S.; Singh, A.K.; Jha, D.K.; Kochhar, R. Controversies in the management of acute pancreatitis: An update. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 2582–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thavanesan, N.; White, S.; Lee, S.; Ratnayake, B.; Oppong, K.W.; Nayar, M.K.; Sharp, L.; Drewes, A.M.; Capurso, G.; De-Madaria, E.; et al. Analgesia in the Initial Management of Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. World J. Surg. 2022, 46, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C. Opioid receptors. Annu. Rev. Med. 2016, 67, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewes, A.M. Definition, diagnosis and treatment strategies for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction—Recommendations of the Nordic Working Group. Scand. J. Pain 2016, 11, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, C.; Olesen, S.S.; Olesen, A.E.; Frøkjaer, J.B.; Andresen, T.; Drewes, A.M. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: Pathophysiology; management. Drugs 2012, 72, 1847–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.D.; Zhang, Z.H.; Jin, J.Z.; Kong, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, D.Y.; Wang, M.F. Effects of narcotic analgesic drugs on human Oddi’s sphincter motility. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 2901–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Banerjee, S.; Charboneau, R.; Barke, R.A.; Roy, S. Morphine Induces Bacterial Translocation in Mice by Compromising Intestinal Barrier Function in a TLR-Dependent Manner. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlass, U.; Dutta, R.; Cheema, H.; George, J.; Sareen, A.; Dixit, A.; Yuan, Z.; Giri, B.; Meng, J.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Morphine worsens the severity and prevents pancreatic regeneration in mouse models of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2018, 67, 600–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.R.; Fűr, G.; Kui, B.; Balla, Z.; Kormányos, E.S.; Orján, E.M.; Tóth, B.; Horváth, G.; Szűcs, E.; Benyhe, S.; et al. Fentanyl but Not Morphine or Buprenorphine Improves the Severity of Necrotizing Acute Pancreatitis in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerveld, B.G.-V.; Gardner, C.J.; Little, P.J.; Hicks, G.A.; Dehaven-Hudkins, D.L. Preclinical studies of opioids and opioid antagonists on gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2004, 16, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashok, A.; Faghih, M.; Azadi, J.R.; Parsa, N.; Fan, C.; Bhullar, F.; Gonzalez, F.G.; Jalaly, N.Y.; Boortalary, T.; Khashab, M.A.; et al. Morphologic Severity of Acute Pancreatitis on Imaging Is Independently Associated with Opioid Dose Requirements in Hospitalized Patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.M.; Pendharkar, S.A.; Asrani, V.M.; Windsor, J.A.; Petrov, M.S. Effect of Intravenous Fluids and Analgesia on Dysmotility in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Pancreas 2017, 46, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, A.; Korytny, A.; Klein, A.; Khoury, Y.; Ben Hur, D.; Braun, E.; Azzam, Z.S.; Ghersin, I. The Association Between Opioid Use and Opioid Type and the Clinical Course and Outcomes of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreas 2022, 51, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoph, C.S.; Joseph, N.; Lucocq, J.; Olesen, S.S.; Huang, W.; Dhar, J.; Samanta, J.; Talukdar, R.; Capurso, G.; Preatoni, P.; et al. No definite associations between opioid doses and severity of acute pancreatitis—Results from a multicentre international prospective study. Pancreatology 2025, 25, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoph, C.S.; Cook, M.E.; Novovic, S.; Hansen, M.B.; Mortensen, M.B.; Nielsen, L.B.J.; Høgsberg, I.M.; Salomon, C.; Neergaard, C.E.L.; Aajwad, A.J.; et al. No Effect of Methylnaltrexone on Acute Pancreatitis Severity: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoph, C.S.; Hesthaven, A.S.; Cook, M.E.; Novovic, S.; Hansen, M.B.; Mortensen, M.B.; Nielsen, L.B.J.; Høgsberg, I.M.; Salomon, C.; Thorlacius-Ussing, O.; et al. Gastrointestinal Transit Time Assessed Using a CT-Based Radiopaque Marker Method in Patients with Acute Pancreatitis During Methylnaltrexone Treatment. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2025, 37, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S.P.; Anderson, M.P.; Maatman, T.K.; Roch, A.M.; Butler, J.R.; Ceppa, E.P.; House, M.G.; Nakeeb, A.; Nguyen, T.K.; Schmidt, C.M.; et al. Opioid analgesia in necrotizing pancreatitis: Incidence and timing of a hidden crisis. Am. J. Surg. 2023, 225, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.L.; Jin, D.X.; Srivoleti, P.; Banks, P.A.; McNabb-Baltar, J. Are Opioid-Naive Patients with Acute Pancreatitis Given Opioid Prescriptions at Discharge? Pancreas 2019, 48, 1397–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Yakah, W.; Freedman, S.D.; Kothari, D.J.; Sheth, S.G. Evaluation of Opioid Use in Acute Pancreatitis in Absence of Chronic Pancreatitis: Absence of Opioid Dependence an Important Feature. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabaudon, M.; Chabanne, R.; Sossou, A.; Bertrand, P.M.; Kauffmann, S.; Chartier, C.; Guérin, R.; Imhoff, E.; Zanre, L.; Brénas, F.; et al. Epidural analgesia in the intensive care unit: An observational series of 121 patients. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2015, 34, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabaudon, M.; Belhadj-Tahar, N.; Rimmelé, T.; Joannes-Boyau, O.; Bulyez, S.; Lefrant, J.Y.; Malledant, Y.; Leone, M.; Abback, P.S.; Tamion, F.; et al. Thoracic epidural analgesia and mortality in acute pancreatitis: A multicenter propensity analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e198–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fu, B.; Su, D.; Fu, X. Impact of early thoracic epidural analgesia in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, e13740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasabuchi, Y.; Yasunaga, H.; Matsui, H.; Lefor, A.K.; Fushimi, K.; Sanui, M. Epidural analgesia is infrequently used in patients with acute pancreatitis: A retrospective cohort study. Acta Gastroenterol. Belg. 2017, 80, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sadowski, S.M.; Andres, A.; Morel, P.; Schiffer, E.; Frossard, J.L.; Platon, A.; Poletti, P.A.; Bühler, L. Epidural anesthesia improves pancreatic perfusion and decreases the severity of acute pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 12448–12456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabaudon, M.; Genevrier, A.; Jaber, S.; Windisch, O.; Bulyez, S.; Laterre, P.-F.; Escudier, E.; Sossou, A.; Guerci, P.; Bertrand, P.-M.; et al. Thoracic epidural analgesia in intensive care unit patients with acute pancreatitis: The EPIPAN multicenter randomized controlled trial. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Gupta, Y.R.; Das, S.; Rai, G.; Gupta, A. Effect of segmental thoracic epidural block on pancreatitis induced organ dysfunction: A preliminary study. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 23, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarano, C.A.; Sandhu, N.S.; Villaluz, J.E. Localizing the pain: Continuous paravertebral nerve blockade in a patient with acute pancreatitis. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e934189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantuani, D.; Luftig, P.A.J.; Herring, A.; Mian, M.; Nagdev, A. Successful emergency pain control for acute pancreatitis with ultrasound guided erector spinae plane blocks. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 1298.e5–1298.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkoundi, A.; Eloukkal, Z.; Bensghir, M.; Belyamani, L.; Lalaoui, S.J. Erector Spinae Plane Block for Hyperalgesic Acute Pancreatitis. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 1055–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, S.G.; Gómez Facundo, H.; Deiros García, C.; Pueyo Periz, E.M.; Ribas Montoliu, R.; Coronado Llanos, D.; Masdeu Castellvi, J.; Martin-Baranera, M. Transversus abdominis plane block in acute pancreatitis pain management. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 44, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintara, S.; Shah, I.; Yakah, W.; Kowalczyk, J.J.; Sorrento, C.; Kandasamy, C.; Ahmed, A.; Freedman, S.D.; Kothari, D.J.; Sheth, S.G. Comparison of Opioid-Based Patient-Controlled Analgesia with Physician-Directed Analgesia in Acute Pancreatitis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, S.S.; Bouwense, S.A.W.; Wildersmith, O.H.G.; Van Goor, H.; Drewes, A.M. Pregabalin reduces pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis in a randomized, controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, A.M.; Kempeneers, M.A.; Andersen, D.K.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Besselink, M.G.; Boermeester, M.A.; Bouwense, S.; Bruno, M.; Freeman, M.; Gress, T.M.; et al. Controversies on the endoscopic and surgical management of pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis: Pros and cons! Gut 2019, 68, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiley, M.M.; Lu, Y.; Vera-Portocarrero, L.P.; Zidan, A.; Westlund, K.N. Intrathecal Gabapentin Enhances the Analgesic Effects of Subtherapeutic Dose Morphine in a Rat Experimental Pancreatitis Model. Anesthesiology 2004, 101, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Vera-Portocarrero, L.P.; Westlund, K.N. Intrathecal Coadministration of D-APV and Morphine Is Maximally Effective in a Rat Experimental Pancreatitis Model. Anesthesiology 2003, 98, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Vera-Portocarrero, L.P.; Ossipov, M.H.; Vardanyan, M.; Lai, J.; Porreca, F. Attenuation of Persistent Experimental Pancreatitis Pain by a Bradykinin B2 Receptor Antagonist. Pancreas 2010, 39, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, A.; Minaiyan, M.; Safaei, A.; Taheri, D. Effect of Diazepam on Severity of Acute Pancreatitis: Possible Involvement of Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptors. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2013, 2013, 484128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, D.K.; Lee, J.K.; Jung, C.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kang, H.R.; Lee, Y.S.; Yoon, J.H.; Joo, K.R.; Chae, M.K.; Baek, Y.H.; et al. Electroacupuncture for abdominal pain relief in patients with acute pancreatitis: A three-arm randomized controlled trial. J. Integr. Med. 2023, 21, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Yin, S.; Zhu, X.; Che, D.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Yan, H.; Gan, D.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; et al. Acupuncture for Relieving Abdominal Pain and Distension in Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 786401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Chen, Z.; Jin, T.; Cai, F.; He, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Guo, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; et al. Traditional Chinese medicine Chaiqinchengqi decoction for patients with acute pancreatitis: A randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2025, 138, 156393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N.; Kuhlmann, L.; Lucocq, J.; Aulenkamp, J.; Knoph, C.S.; Olesen, S.S.; Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M.; Windsor, J.A.; Drewes, A.M.; Pandanaboyana, S. A Systematic Review of Pain Assessment Domains in Acute Pancreatitis Randomised Controlled Trials. Pancreas 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, L.; Pogatzki-Zahn, E.M.; Joseph, N.; Lucocq, J.; Aulenkamp, J.; Knoph, C.S.; Olesen, S.S.; Windsor, J.A.; Drewes, A.M.; Pandanaboyana, S. Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Acute Pancreatitis Pain Core Outcome Set (CAPPOS): Study Protocol. Pancreas 2025, 54, e661–e666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, S.; Crowe, S.; Watson, W.; Rasmussen, B.; Wynter, K.; Holton, S. End PJ Paralysis: An initiative to reduce patient’s functional decline. Aust. Nurs. Midwifery J. 2020, 27, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Capurso, G.; Ponz de Leon Pisani, R.; Lauri, G.; Archibugi, L.; Hegyi, P.; Papachristou, G.I.; Pandanaboyana, S.; Maisonneuve, P.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; De-Madaria, E. Clinical usefulness of scoring systems to predict severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis with pre and post-test probability assessment. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2023, 11, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Knoph, C.S.; Pandanaboyana, S. Optimising Pain Relief in Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010113

Knoph CS, Pandanaboyana S. Optimising Pain Relief in Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010113

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnoph, Cecilie Siggaard, and Sanjay Pandanaboyana. 2026. "Optimising Pain Relief in Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010113

APA StyleKnoph, C. S., & Pandanaboyana, S. (2026). Optimising Pain Relief in Acute Pancreatitis: An Evidence-Based Approach. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 113. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010113