Planned vs. Performed Treatment Regimens in Diabetic Macular Edema: Real-World Evidence from the PACIFIC Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Treatments

3.3. Treatment Regimens

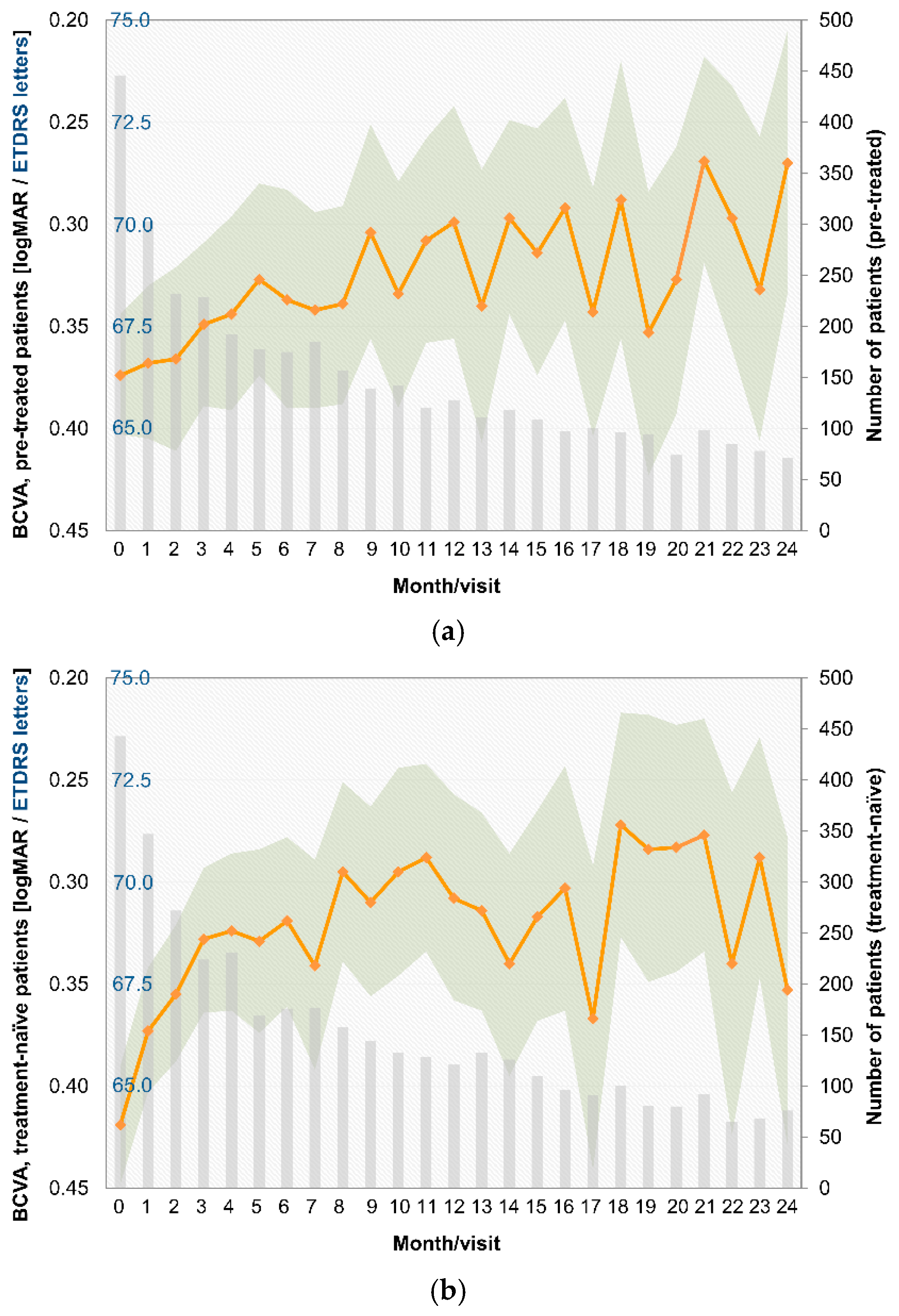

3.4. Visual Acuity

3.5. Adverse Events

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Over the last few years, a learning curve has been recognized, which is reflected in key parameters. The median treatment delay was 6 days for pretreated patients and 5 days for treatment-naïve patients in this study. This is notably shorter than in the preceding OCEAN study (conducted between 2011 and 2016), which reported a median treatment delay of approximately 21 days for DME patients [23]. This finding indicates an increased awareness of the importance of early treatment among ophthalmologists in recent years. Success and long-term preservation of visual function depend largely on the function at the start of treatment [24,25];

- (2)

- The intended treatment pattern showed notable differences compared to the actually performed regimen. At baseline, a “fixed” scheme and “pro re nata” were the most commonly used treatment regimens. This would have been in accordance with the DOG guidelines, which recommend a “fixed” scheme for the first 6 months, followed by “pro re nata” treatment [10]. However, in reality, these regimens were only performed for a small percentage of patients. This finding indicates that undertreatment is still an issue for DME patients [26]. Over the course of the observational period, a shift toward a “monitor and extend” regimen was observed based on the statistical derivation. It is possible that due to the study’s defined query and temporal limits, the data led to an interpretation of the study as a “monitor and extend” regimen in many cases, even if not intended by the physician. It seems important to look for unconscious influences and other relevant factors [27]. In the future, attention should be given to realistic agreements to improve the quality of educational discussions and provide informed consent;

- (3)

- Concomitant laser treatment has much less significance than described in clinical studies. Approximately 41–64% of treatment-naïve DME patients (DRCR.net Protocol T from 2012 to 2014) received at least one laser treatment over 2 years, and 23% of pretreated patients and 15% of treatment-naïve patients among the PACIFIC participants underwent concomitant laser treatment. However, it remains unclear whether this difference is ultimately due to the non-interventional nature of the study or to the basic philosophy of a less aggressive combined approach in Europe vs. the USA [28]. Presumably, both influences are likely to play a role if the decision to use a focal-grid laser in addition to anti-VEGF drugs does not follow a systematic algorithm. Although the stability of the achieved visual acuity gain is more relevant for retreatment than retinal morphology is, given the proportions of persistent fluid in DME [11], the strategy may not always be effective because of unclear expectations and perceived non-response. Although combined laser treatment did not show a general benefit in studies, there is indirect evidence for the benefits of targeted supplementary laser treatment over time [29];

- (4)

- The trend toward low treatment numbers was similar between naïve and pretreated patients. Pretreated patients in the PACIFIC study received a mean of 10.6 injections, and treatment-naïve patients received 9.2 injections (among those patients with documentation for at least two years). Thus, patients received notably more injections than in the previous observational OCEAN study (5.5 injections) [30], but still fewer injections than in clinical trials [31,32];

- (5)

- Treatment discontinuation is still a relevant problem in this treatment indication [33]. Aggravated general conditions often cause patients to discontinue treatment. In the PACIFIC study, patients with very high HbA1c values (>9%) were more likely to be discontinued prematurely and experience more AEs. There were no major outliers in terms of insurance or race, but the analyzed cohort was quite homogeneous and of Central European ancestry [34].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DME | Diabetic Macular Edema |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| BCVA | Best Corrected Visual Acuity |

| NIS | Non-Interventional Study |

| SES | Safety Evaluation Set |

| FAS | Full Analysis Set |

| AEs | Adverse Events |

| SAEs | Severe Adverse Events |

| SADRs | Serious Adverse Drug Reactions |

| MedDRA | Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities |

| DOG | Deutsche Ophthalmologische Gesellschaft (German Ophthalmological Society) |

Appendix A

| Ophthalmological Findings, n (%) a | Pre-Treated N = 458 | Treatment-Naïve N = 452 |

|---|---|---|

| Subretinal fluid with foveal involvement | 142 (31.00%) | 170 (37.61%) |

| Subretinal fluid without foveal involvement | 47 (10.26%) | 66 (14.60%) |

| Cystoid fluid inclusion with foveal involvement | 265 (57.86%) | 274 (60.62%) |

| Cystoid fluid inclusion without foveal involvement | 127 (27.73%) | 158 (34.96%) |

| Diffuse retinal thickening | 183 (39.96%) | 153 (33.85%) |

| Ischemic areas | 55 (12.01%) | 59 (13.05%) |

| Bleeding or punctate bleeding | 275 (60.04%) | 288 (63.72%) |

| Exudate | 155 (33.84%) | 158 (34.96%) |

| Intraretinal microvascular anomalies | 76 (16.59%) | 62 (13.72%) |

| Proliferative diabetic retinopathy | 63 (13.76%) | 74 (16.37%) |

| Cataract | 142 (31.00%) | 140 (30.97%) |

Appendix B

| PI | Center | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Christos Haritoglou | Gemeinschaftspraxis Profs. Haritoglou, Schultheiß, Klink | Munich |

| Martin Bechmann | Augenklinik Airport GmbH | Munich Airport |

| Daniela Erhard | Augenklinik Airport GmbH | Munich Airport |

| Shervin Mir Mohi Sefat | Augenklinik Airport GmbH | Munich Airport |

| Gabriele Kuba | Praxis Gabriele Kuba | Munich |

| Ines Lanzl | Institut Rund ums Auge, I. Lanzl & W. Reich | Prien/Chiemsee |

| Richard Wertheimer | Augenärzte im Arabellahaus, Richard Wertheimer, Katharina Wittmer | Munich |

| Udo Heuer | MEC Augenärzte, Udo Heuer | Hamburg |

| Angela Timm | Augenärztliche Gemeinschaftspraxis. M. Bayer, H. Schneider und A. Timm | Wismar |

| Bertram Machnik | Praxis Bertram Machnik | Hamburg |

| Peter Kaupke | Gemeinschaftspraxis Kaupke, Görges, Miebach und Ehrich | Hamburg |

| Semse Özmen | Augenarztpraxis Gemeinschaftspraxis Wedel | Wedel |

| Christine Onken | Augenarztpraxis Gemeinschaftspraxis Wedel | Wedel |

| Soheyl Asadi | Praxis Augenärzte am Weidenbaumsweg | Hamburg |

| Smbat Berger | Smbat Berger | Bremerhaven |

| Martin Winter | Praxis Martin Winter | Bremen |

| Martin Scheffler | Praxis Martin Scheffler | Rhauderfehn |

| Stephan Kilias | Gemeinschaftspraxis Kilias und Fetter | Hoppegarten |

| Janek Häntzschel | Gemeinschaftspraxis Häntzschel, Later | Pirna |

| Linda Later | Gemeinschaftspraxis Häntzschel, Later | Pirna |

| Marc Marré | Gemeinschaftspraxis Marc Marré | Dresden |

| Lada Matschke | Praxis Lada Matschke | Neubrandenburg |

| Kyra Lauritzen | Kyra Lauritzen | Buchholz i.d.N. |

| Bilal Chamat | Berlin Eye Clinic, Bilal Chamat, FEBO | Berlin |

| Stefan Heinrich | Praxis Stefan Heinrich | Berlin |

| Mehrinfar Ben | Gemeinschaftspraxis Dres. Pahlitzsch, Grüngreiff | Berlin |

| Kathleen Steinberg | Praxis Kathleen Steinberg | Berlin |

| Jochen Thieme | Jochen Thieme | Berlin |

| Mohammed O. Ramez | Praxis M. Osman Ramez | Buxtehude |

| Malek Moubid | Augenarztpraxis Malek Moubid | Buxtehude |

| Christoph Wehner | Praxis Christoph Wehner, Andreas Meyer-Rößler | Bremervörde |

| Mayk Steiner | Gemeinschaftspraxis Anke Steiner und Mayk Steiner | Dannenberg |

| Anke Steiner | Gemeinschaftspraxis Anke Steiner und Mayk Steiner | Dannenberg |

| Alper Bilgic | Alpha Vision Alper Bilgic, Ahmed Galal | Bremerhaven |

| Peter Ruokonen | Gemeinschaftspraxis Baecker und Ruokonen | Berlin |

| Anaelle Laurent | Augenklinik Berlin-Marzahn GmbH | Berlin |

| Sorin Draghici | Augenarztpraxis Draghici & Kontopoulos | Berlin |

| Theodoros Kontopoulos | Augenarztpraxis Draghici & Kontopoulos | Berlin |

| Mirjam Gross | Augenarztpraxis für Gross und Klein | Berlin |

| Thomas Kube | Praxis Thomas Kube | Bielefeld |

| Erik Beeke | Visual eins Ärztehaus-Praxis/Klinik | Osnabrück |

| Susanne Eller-Woywod | Augenärzte Goldmann, Dr.Engels, Dr.Grotheheide, Dr.Eller-Woywod | Gütersloh |

| Sabine Kaps | Sabine Kaps | Obernkirchen |

| Nikolai Holak | Nikolai Holak | Salzgitter |

| Ole Krüger | Augenärzte am Bankplatz Dres. Heinichen, Ahrens, Krüger | Braunschweig |

| T. Heinichen | Augenärzte am Bankplatz Dres. Heinichen, Ahrens, Krüger | Braunschweig |

| S. Heinichen | Augenärzte am Bankplatz Dres. Heinichen, Ahrens, Krüger | Braunschweig |

| M. Ahrens | Augenärzte am Bankplatz Dres. Heinichen, Ahrens, Krüger | Braunschweig |

| Annette Handstein | Praxis Annette Handstein | Paderborn |

| Sandra Festag | Sandra Festag | Petershagen |

| Christof Lenz | Christof Ulrich Lenz | Paderborn |

| Frank-Christian Nickel | Frank Nickel-Augenärztliche Gemeinschaftspraxis | Peine |

| Alexander Petzold | Augenzentrum am Johannisplatz, Alexander Petzold | Leipzig |

| Thomas Hammer | Praxis Thomas Hammer | Halle (Saale) |

| Gernot Duncker | Gernot Duncker-MVZ Augenheilkunde Mitteldeutschland GmbH | Halle (Saale) |

| Kerstin Hellmund | Praxis Kerstin Hellmund | Dresden |

| Matthias Müller-Holz | Überörtliche Gemeinschaftspraxis, Matthias Müller-Holz | Dresden |

| Tobias Riedel | Überörtliche Gemeinschaftspraxis, Matthias Müller-Holz | Dresden |

| Regina Matthes | Praxis Regina Matthes | Dresden |

| Nasser Al-Ashi | Oberlausitz Kliniken gGmbH, Nasser Al-Ashi | Bautzen |

| Jakub Chmielowski | Praxis Jakub Chmielowski | Plauen |

| Simo Murovski | Praxis Simo Murovski | Zschopau |

| Stephan Kretschmar | Praxis Stephan Kretschmar | Bautzen |

| Dirk Pohlmann | Augenzentrum Osthessen | Fulda |

| Houcem Ghribi | Houcem Ghribi | Gifhorn |

| Wolfram Lieschke | Praxis Wolfram Lieschke | Leipzig |

| Christian Ksinsik | Augenarztpraxis am Glacis | Torgau |

| Alain de Alba Castilla | Augenarztpraxis am Glacis | Torgau |

| Jorge Cantu Dibildox | Augenarztpraxis am Glacis | Torgau |

| Alexander Goldberg | Alexander Goldberg | Coswig |

| Alexander Stoll | Praxis Alexander Stoll | Chemnitz |

| Agnes Ute Porstmann | Elbland Augenzentrum am Elblandklinikum-Agnes Ute Porstmann | Radebeul |

| Gregor Schwert | MVZ Beckum I-Röschinger, Grewe und Schwert | Beckum |

| Ulrich Thelen | Augenärzte Klosterstraße | Münster |

| Elisabeth Bator-Banasik | GP Elisabeth Bator-Banasik, Heidi Fischer | Ahaus |

| Farsad Fanihagh | Gemeinschaftspraxis Ch.-L. Kallmann und F. Fanihagh | Ratingen |

| Stephan Dunker | Praxis Stephan Dunker | Troisdorf |

| Maren Unger | Augenzentrum Brühl | Brühl |

| Frederik Wiegand | Gemeinschaftspraxis Radetzky, Jurek-Becker und Looke, Frederik Wiegand | Neuwied |

| Hendrik Fuchs | Belenus Augenzentrum Siegen Service GbR | Siegen |

| Hans-Ulrich Frank | Belenus Augenzentrum Siegen Service GbR | Siegen |

| Omar Mohamed Alnahrawy | Augencentrum Koblenz, M. Derse, C. Papoulis und Kollegen | Koblenz |

| Andreas Schmidt | Augenzentrum Andernach Andreas Schmidt, C. Schmidt-Dudziak | Andernach |

| Christian Abel | Praxis Christian Abel | Trier |

| Markus Strauß | Praxis Markus Strauß | Saarbrücken |

| Stefan Pfennigsdorf | Praxis Stefan Pfennigsdorf | Polch |

| Eduard Berenstein | Augencentrum Koblenz-Höhr-Grenzhausen Derse, Papoulis und Kollegen | Höhr-Grenzhausen |

| Tatyana Lazarova-Hristova | Praxis Fazil Peru | Frankfurt |

| Stefan Müller | Praxis Stefan Müller | Neustadt |

| Martin Rauber | Gemeinschaftspraxis Zuche und Rauber | Saarburg |

| Andreas Liermann | Andreas Liermann | Neustadt |

| Isolde Olivas | Praxis Isolde Olivas | Heddenheim |

| Martin Mundschenk | Praxis Martin Mundschenk | Worms |

| Gerber Tina | Praxis Tina Gerber | Mutterstadt |

| Viktor Gossmann | Praxis Viktor Gossmann | Ludwigshafen |

| Babak Mohammadi | Praxis Babak Mohammadi | Düsseldorf |

| Hakan Kaymak | Breyer, Kaymak und Klabe Augenchirurgie | Düsseldorf |

| Johannes Bohnen | LUMEDICO Johannes Bohnen | Düsseldorf |

| Matthias Grüb | Praxis Matthias Grüb | Breisach |

| Andrea Wißmann | Praxis Hartmut Karl König | Baden-Baden |

| Anita Lis-Kowalczyk | Praxis Anita Lis-Kowalczyk | Freudenstadt |

| Dirk Eberhardt | Gemeinschaftspraxis B. Entenmann und D. Eberhardt | Waldshut-Tiengen |

| Beatrix Entenmann | Gemeinschaftspraxis B. Entenmann und D. Eberhardt | Waldshut-Tiengen |

| David Schell | Praxis David Schell | Memmingen |

| Christian Scherer | Gemeinschaftspraxis Renata Scherer und Christian Scherer | Augsburg |

| Thilo Schimitzek | Augenklinik Kempten, Thilo Schimitzek | Kempten |

| Marianne Liedtke-Maier | Augen-Diagnostik-Zentrum Maier, Liedtke-Maier | Hösbach |

| Othmar Keller | Überörtliche BAG Othmar Keller, Susanne Müller | Herrsching |

| Jürgen Garus | Praxis Jürgen Garus | Pfaffenhofen an der Ilm |

| Uwe Schütz | GP Nikolaus Hillenbrand, Uwe Schütz | Ehingen |

| Christian Schäferhoff | Christian Schäferhoff | Esslingen |

| Barbara Fuchs-Koelwel | Barbara Fuchs-Koelwel | Regensburg |

| Klaus Königsreuther | Praxis Klaus Königsreuther | Eckental/Eschenau |

| Christoph Winkler v. Mohrenfels | Praxis Christoph Winkler v. Mohrenfels | Neutraubling |

| Magda Rau | Privatklinik Rau | Cham |

| Thomas Brandl | Praxis Thomas Brandl | Straubing |

| Georgios Siochos | Praxis Georgios Siochos | Karlsfeld |

| Janna Harder | Janna Harder | Munich |

| Stephan Eckert | Gemeinschaftspraxis Kemmerling und Eckert | Sindelfingen |

| Kamil Weinhold | Praxis Kamil Weinhold | Karlsruhe |

| Axel Hautzinger | Augenärzte Dres. Reichert und Hautzinger | Frankenthal |

| Ralph Maria Alles | Praxis Ralph Maria Alles | Saarlouis |

| Ralf Schmitt | Augen-Zentrum im Medizeum, Ralf Schmitt | Saarbrücken |

| Susanne Grewing | GP Ralf Grewing und Kollegen | Kaiserslautern |

| Michael Kusber | Michael Kusber | Bad Arolsen |

| Björn Feldner | Augenärztliches MVZ Friedländer Weg-Dres. Genée, Feldner und Kolck-Bölling | Göttingen |

| Stefan Kienzle | Praxis Kienzle, Lojewski und Nolte | Herzberg |

| Christian Gittner | Christian Gittner | Einbeck |

| Pia Kirchner | Gemeinschaftspraxis Schröder, Hoerauf, Pia Kirchner | Göttingen |

| Waldemar Jendritza | Praxis Dres. Jendritza | Ludwigshafen |

| Annette Brusis | Praxis Annette Brusis | Heppenheim |

| Harry Domack | Gemeinschaftspraxis Domack, Best und Schmidt | Schweinfurt |

| Peter Lang | Gemeinschaftspraxis H. Lang, P. Lang, K. Gottschalk | Nürnberg |

| Judith Becker | Überörtliche BAG Haupt, Spraul, Teuchert und Zorn | Ulm |

| Carolin Schwamberger | MVZ Augen Rombold, Niederdellmann und Kollegen | Friedberg |

| Martin Lambert | ÜöBAG Dankwart, Schmidl. Lambert, Schmidt | Rüsselsheim |

| Frank Koch | Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main-Augenklinik | Frankfurt |

| Svenja Deuchler | Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main-Augenklinik | Frankfurt |

| Ninel Kenikstul | Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main-Augenklinik | Frankfurt |

| Pankaj Singh | Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main-Augenklinik | Frankfurt |

| Katrin Lorenz | Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz | Mainz |

| Anna Beck | Universitätsmedizin der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz | Mainz |

| Helmut Sachs | Städtisches Klinikum Dresden | Dresden |

| Merle Schrader | Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg | Oldenburg |

| Sabine Aisenbrey | Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg | Oldenburg |

| Guido Esper | Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg | Oldenburg |

| Menelaos Pipilis | Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg | Oldenburg |

| Roland Richter | Augenärzte am Brand 12-Dres. Müller-Richter-Coracas | Mainz |

| Gregor Eberlein | Klinikum Augsburg AöR-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Augsburg |

| Arthur Mueller | Klinikum Augsburg AöR-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Augsburg |

| Jürgen Pleines | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Dieter Hagedorn | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Klaas Heidemann | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Nikolaus Lohmann | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Matthias Meyer | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Nakisa Amiri | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Michael Witteborn | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Hansgeorg Albrechtr | ZG Zentrum Gesundheit GmbH | Leer |

| Claudia Lanzrath | Berufsausübungsgemeinschaft Zentrum Gesundheit Oldenburg GbR | Oldenburg |

| Daniela Fromm | Berufsausübungsgemeinschaft Zentrum Gesundheit Oldenburg GbR | Oldenburg |

| Ramin Khoramnia | Universitäts-Augenklinik Heidelberg | Heidelberg |

| Gerd Auffarth | Universitäts-Augenklinik Heidelberg | Heidelberg |

| Dirk Sandner | GWT-TUD GmbH Sandner | Dresden |

| Matthe Egbert | GWT-TUD GmbH Sandner | Dresden |

| Hüsnü Berk | St. Elisabeth Krankenhaus Köln-Hohenlind Berk | Cologne |

| V. Romanou-Papadopoulou | MVZ der Klinik Dardenne GmbH, Vassiliki Romanou-Papadopoulou | Bonn-Bad Godesberg |

| Hans-Wilhelm Große | MVZ der Klinik Dardenne GmbH, Vassiliki Romanou-Papadopoulou | Bonn-Bad Godesberg |

| Jasmin Bartling | MVZ der Klinik Dardenne GmbH, Vassiliki Romanou-Papadopoulou | Bonn-Bad Godesberg |

| Helmut Höh | Dietrich-Bonhoeffer-Klinikum | Neubrandenburg |

| Mathias Schwanengel | Dietrich-Bonhoeffer-Klinikum | Neubrandenburg |

| Salvatore Grisanti | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Lübeck |

| Martin Rudolf | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Lübeck |

| Matthias Lüke | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Lübeck |

| Mahdy Ranjbar | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Lübeck |

| Laurenz Sonnentag | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein-Klinik für Augenheilkunde | Lübeck |

| Thomas Ach | Universitätsklinikum Würzburg Thomas Ach | Würzburg |

| Jost Hillenkamp | Universitätsklinikum Würzburg Thomas Ach | Würzburg |

| Kerstin Stange | Augenarztpraxis Stange und Langner | Borna |

| Andrea Langner | Augenarztpraxis Stange und Langner | Borna |

| Ulrich Schaudig | Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH-Asklepios Klinik Barmbek | Hamburg |

| Kais Al-Samir | Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH-Asklepios Klinik Barmbek | Hamburg |

| Birthe Stemplewitz | Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH-Asklepios Klinik Barmbek | Hamburg |

| Katinka Westermann-Lammers | Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH-Asklepios Klinik Barmbek | Hamburg |

| Gelareh Winter | Asklepios Kliniken Hamburg GmbH-Asklepios Klinik Barmbek | Hamburg |

| Peter Großkopf | Augenzentrum Hochrhein | Bad Säckingen |

| Gudrun Papadopoulos | Augenzentrum Hochrhein | Bad Säckingen |

| Sebastian Tudor | Augenzentrum Hochrhein | Bad Säckingen |

| Olga Sartorius | Praxis Olga Sartorius | Erkrath |

| Focke Ziemssen Focke | Universitäts-Augenklinik Tübingen, Focke Ziemssen | Tübingen |

| Véronique Kitiratschky | Ortenau Klinikum Offenburg-Gengenbach-St. Josefsklinik | Offenburg |

| Amin Gamael | MVZ der Universitätsmedizin Rostock | Rostock |

| Joachim Schmidt | Lichtblick MVZ Moers GmbH | Moers |

| Roland Koch | Lichtblick MVZ Moers GmbH | Moers |

| Stefanie Schmickler | Augen-Zentrum-Nordwest (MVZ) | Ahaus |

| Olaf Cartsburg | Augen-Zentrum-Nordwest (MVZ) | Ahaus |

| Jens Schrecker Jens | Rudolf Virchow Klinikum Glauchau gGmbH | Glauchau |

| Ute Jüst | Rudolf Virchow Klinikum Glauchau gGmbH | Glauchau |

| Chris P. Lohmann | Klinikum rechts der Isar-Augenklinik und Poliklinik | Munich |

| Georg Spital | Augenärzte am St. Franziskus-Hospital | Münster |

| Frederike Hochhaus | Frederike Hochhaus | Bockhorn |

| Berthold Seitz | Universität des Saarlandes | Homburg/Saar |

| Karl-Heinz Emmerich | Klinikum Darmstadt GmbH | Darmstadt-Eberstadt |

| Andreas Krieb | Klinikum Darmstadt GmbH | Darmstadt-Eberstadt |

| Monica Lang | Klinikum Darmstadt GmbH | Darmstadt-Eberstadt |

| Ralf Ungerechts | Klinikum Darmstadt GmbH | Darmstadt-Eberstadt |

| Christoph Ehlken | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel | Kiel |

| Claus von der Burchard | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel | Kiel |

| Anna-Maria Kirsch | Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel | Kiel |

| Ayman Barouni | Ayman Barouni | Hückelhoven |

| Andrea Wißmann | Praxis Kristin Schubert | Ettlingen |

| Lena Goldammer | Praxis Lena Goldammer | Celle |

| Ralf-H. Gerl | Überörtliche BAG Gerl Raesfeld | Raesfeld |

| Matthias Gerl | Augenklinik Ahaus GmbH & Co. KG | Ahaus |

| Ralf-H. Gerl | Überörtliche BAG Gerl und Kollegen in Rheine | Rheine |

| Pascal Hasler | Universitätsspital Basel Augenklinik | Basel |

| Patrik Kloos | Augenklinik Wil | Wil |

| Marcel Menke | Kantonsspital Aarau Augenklinik | Aarau |

| Ioannis Petropoulos | Centre Ophtalmologique de Rive | Geneva |

| Veronika Vaclavik | Hôpital Cantonal de Fribourg Ophtalmologie | Fribourg |

| Gabriele Thumann | Hôpitaux Universitaires Genève | Geneva |

| Fabrizio Branca | Augenzentrum Bahnhof Basel | Basel |

| Ralf Kiel | Centre neuchâtelois d’ophtalmologie | Neuchatel |

| Pascal Imesch | Imesch AG | Muri |

| Daniel Barthelmes | UniversitätsSpital Zürich Augenklinik | Zürich |

| R.J. Wouters | Oogcentrum Noordholland | Heerhugowaard |

| L.J. Noordzij | Maasstad Ziekenhuis | Rotterdam |

| Janneke van Lith | St. Elisabeth Ziekenhuis | Tilburg |

| V.P.T. Hoppenreijs | Deventer Ziekenhuis | Deventer |

| Mrs. M. Smeets | Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis | ‘s-Hertogenbosch |

| Vicky Boeyden | Ziekenhuis ZorgSaam Zeeuws Vlaanderen | Terneuzen |

| Thorsten Stolwijk | StolMed Oogklinieken | Bergen op Zoom |

| J.P. Martinez Ciriano | Oogziekenhuis Rotterdam | Rotterdam |

References

- Comyn, O.; Sivaprasad, S.; Peto, T.; Neveu, M.M.; Holder, G.E.; Xing, W.; Bunce, C.V.; Patel, P.J.; Egan, C.A.; Bainbridge, J.W.; et al. A randomized trial to assess functional and structural effects of ranibizumab versus laser in diabetic macular edema (the LUCIDATE study). Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massin, P.; Bandello, F.; Garweg, J.G.; Hansen, L.L.; Harding, S.P.; Larsen, M.; Mitchell, P.; Sharp, D.; Wolf-Schnurrbusch, U.E.K.; Gekkieva, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in diabetic macular edema (RESOLVE Study): A 12-month, randomized, controlled, double-masked, multicenter phase II study. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2399–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Brown, D.M.; Marcus, D.M.; Boyer, D.S.; Patel, S.; Feiner, L.; Gibson, A.; Sy, J.; Rundle, A.C.; Hopkins, J.J.; et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: Results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, T.; Li, X.; Koh, A.; Lai, T.Y.; Lee, F.L.; Lee, W.K.; Ma, Z.; Ohji, M.; Tan, N.; Cha, S.B.; et al. The REVEAL Study: Ranibizumab Monotherapy or Combined with Laser versus Laser Monotherapy in Asian Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1402–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodjikian, L.; Lecleire-Collet, A.; Dot, C.; Le Lez, M.; Baillif, S.; Erginay, A.; Souied, E.; Fourmaux, E.; Gain, P.; Ponthieux, A. ETOILE: Real-World Evidence of 24 Months of Ranibizumab 0.5 mg in Patients with Visual Impairment Due to Diabetic Macular Edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 2307–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Shimura, M.; Kitano, S.; Ohji, M.; Ogura, Y.; Yamashita, H.; Suzaki, M.; Mori, K.; Ohashi, Y.; Yap, P.S.; et al. Impact on visual acuity and psychological outcomes of ranibizumab and subsequent treatment for diabetic macular edema in Japan (MERCURY). Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Aken, E.; Favreau, M.; Ramboer, E.; Denhaerynck, K.; MacDonald, K.; Abraham, I.; Brié, H. Real-World Outcomes in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema Treated Long Term with Ranibizumab (VISION Study). Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 4173–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.; Sheidow, T.G.; Farah, M.E.; Mahmood, S.; Minnella, A.M.; Eter, N.; Eldem, B.; Al-Dhibi, H.; Macfadden, W.; Parikh, S.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of ranibizumab 0.5 mg in treatment-naïve patients with diabetic macular edema: Results from the real-world global LUMINOUS study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michl, M.; Fabianska, M.; Seeböck, P.; Sadeghipour, A.; Haj Najeeb, B.; Bogunovic, H.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.M.; Gerendas, B.S. Automated quantification of macular fluid in retinal diseases and their response to anti-VEGF therapy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- German Society of Ophthalmology (DOG); German Retina Society (RG); Professional Association of Ophthalmologists in Germany (BVA). Statement of the German Ophthalmological Society, the German Retina Society, and the Professional Association of Ophthalmologists in Germany on treatment of diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmologe 2021, 118 (Suppl. S1), 40–67. [CrossRef]

- Kalur, A.; Iyer, A.I.; Muste, J.C.; Talcott, K.E.; Singh, R.P. Impact of retinal fluid in patients with diabetic macular edema treated with anti-VEGF in routine clinical practice. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 58, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.A.; Glassman, A.R.; Ayala, A.R.; Jampol, L.M.; Bressler, N.M.; Bressler, S.B.; Brucker, A.J.; Ferris, F.L.; Hampton, G.R.; Jhaveri, C.; et al. Aflibercept, Bevacizumab, or Ranibizumab for Diabetic Macular Edema: Two-Year Results from a Comparative Effectiveness Randomized Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elman, M.J.; Ayala, A.; Bressler, N.M.; Browning, D.; Flaxel, C.J.; Glassman, A.R.; Jampol, L.M.; Stone, T.W.; Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Intravitreal Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema with prompt versus deferred laser treatment: 5-year randomized trial results. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemssen, F.; Schlottman, P.G.; Lim, J.I.; Agostini, H.; Lang, G.E.; Bandello, F. Initiation of intravitreal aflibercept injection treatment in patients with diabetic macular edema: A review of VIVID-DME and VISTA-DME data. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2016, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, P.; Bandello, F.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Lang, G.E.; Massin, P.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Sutter, F.; Simader, C.; Burian, G.; Gerstner, O.; et al. The RESTORE study: Ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U.; Do, D.V.; Holz, F.G.; Boyer, D.S.; Midena, E.; Heier, J.S.; Terasaki, H.; Kaiser, P.K.; Marcus, D.M.; et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Edema: 100-Week Results From the VISTA and VIVID Studies. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2044–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, D.S.; Yoon, Y.H.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Bandello, F.; Maturi, R.K.; Augustin, A.J.; Li, X.Y.; Cui, H.; Hashad, Y.; Whitcup, S.M.; et al. Three-year, randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1904–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, L.Z.; Sivaprasad, S.; Crosby-Nwaobi, R.; Saihan, Z.; Karampelas, M.; Bunce, C.; Peto, T.; Hykin, P.G. A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial comparing a combination of repeated intravitreal Ozurdex and macular laser therapy versus macular laser only in center-involving diabetic macular edema (OZLASE study). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.M.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Marcus, D.M.; Boyer, D.S.; Patel, S.; Feiner, L.; Schlottmann, P.G.; Rundle, A.C.; Zhang, J.; Rubio, R.G.; et al. Long-term outcomes of ranibizumab therapy for diabetic macular edema: The 36-month results from two phase III trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 2013–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophie, R.; Lu, N.; Campochiaro, P.A. Predictors of Functional and Anatomic Outcomes in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with Ranibizumab. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G.E.; Berta, A.; Eldem, B.M.; Simader, C.; Sharp, D.; Holz, F.G.; Sutter, F.; Gerstner, O.; Mitchell, P.; RESTORE Extension Study Group. Two-year safety and efficacy of ranibizumab 0.5 mg in diabetic macular edema: Interim analysis of the RESTORE extension study. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 2004–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.I.; Kim, S.J.; Bailey, S.T.; Kovach, J.L.; Vemulakonda, G.A.; Ying, G.S.; Flaxel, C.J.; American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Retina/Vitreous Committee. Diabetic Retinopathy Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, P75–P162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemssen, F.; Bertelmann, T.; Hufenbach, U.; Scheffler, M.; Liakopoulos, S.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; OCEAN study group. Delayed treatment initiation of more than 2 weeks. Relevance for possible gain of visual acuity after anti-VEGF therapy under real life conditions (interim analysis of the prospective OCEAN study). Ophthalmologe 2016, 113, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugel, P.U.; Hillenkamp, J.; Sivaprasad, S.; Vögeler, J.; Mousseau, M.; Wenzel, A.; Margaron, P.; Hashmonay, R.; Massin, P. Baseline visual acuity strongly predicts visual acuity gain in patients with diabetic macular edema following anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment across trials. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.A.; Glassman, A.R.; Ayala, A.R.; Jampol, L.M.; Aiello, L.P.; Antoszyk, A.N.; Arnold-Bush, B.; Baker, C.W.; Bressler, N.M.; Browning, D.J.; et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Tabano, D.; Kuo, B.L.; LaPrise, A.; Leng, T.; Kim, E.; Hatfield, M.; Garmo, V. How intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor initial dosing impacts patient outcomes in diabetic macular oedema. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pan, J.; Xu, Y.; Dai, Z.; Fang, Q. Exploring the factors influencing the timely intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment in patients with diabetic macular edema: A qualitative interview study using the COM-B model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Cao, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zai, X.; Yan, Z. Anti-VEGF monotherapy versus anti-VEGF therapy combined with laser or intravitreal glucocorticoid therapy for diabetic macular edema: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 2679–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemssen, F.; Cruess, A.; Dunger-Baldauf, C.; Margaron, P.; Snow, H.; Strain, W.D. Ranibizumab in diabetic macular edema–a benefit–risk analysis of ranibizumab 0.5 mg PRN versus laser treatment. Eur. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Ziemssen, F.; Wachtlin, J.; Kuehlewein, L.; Gamulescu, M.A.; Bertelmann, T.; Feucht, N.; Voegeler, J.; Koch, M.; Liakopoulos, S.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; et al. Intravitreal Ranibizumab Therapy for Diabetic Macular Edema in Routine Practice: Two-Year Real-Life Data from a Noninterventional, Multicenter Study in Germany. Diabetes Ther. Res. Treat. Educ. Diabetes Relat. Disord. 2018, 9, 2271–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.A.; Glassman, A.R.; Jampol, L.M.; Aiello, L.P.; Antoszyk, A.N.; Baker, C.W.; Bressler, N.M.; Browning, D.J.; Connor, C.G.; Elman, M.J.; et al. Association of baseline visual acuity and retinal thickness with 1-Year efficacy of aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016, 134, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, J.F.; Wykoff, C.C.; Clark, W.L.; Bruce, B.B.; Boyer, D.S.; Brown, D.M.; TREX-DME Study Group. Randomized trial of treat and extend ranibizumab with and without navigated laser for diabetic macular edema: TREX-DME 1 year outcomes. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peto, T.; Akerele, T.; Sagkriotis, A.; Zappacosta, S.; Clemens, A.; Chakravarthy, U. Treatment patterns and persistence rates with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for diabetic macular edema in the UK: A real-world study. Diabet. Med. 2022, 39, e14746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, N.A.; Greenlee, T.E.; Iyer, A.I.; Conti, T.F.; Chen, A.X.; Singh, R.P. Racial, Ethnic, and Insurance-Based Disparities Upon Initiation of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy for Diabetic Macular Edema in the US. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantrell, R.A.; Lum, F.; Chia, Y.; Morse, L.S.; Rich, W.L.; Salman, C.A.; Willis, J.R. Treatment Patterns for Diabetic Macular Edema: An Intelligent Research in Sight (IRIS®) Registry Analysis. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, B.L.; Tabano, D.; Garmo, V.; Kim, E.; Leng, T.; Hatfield, M.; LaPrise, A.; Singh, R.P. Long-term Treatment Patterns for Diabetic Macular Edema: Up to 6-Year Follow-up in the IRIS® Registry. Ophthalmol. Retina 2024, 8, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziemssen, F.; Sylvanowicz, M.; Amoaku, W.M.; Aslam, T.; Eldem, B.; Finger, R.P.; Gale, R.P.; Kodjikian, L.; Korobelnik, J.F.; Xiaofeng, L.; et al. Improving Clinical Management of Diabetic Macular Edema: Insights from a Global Survey of Patients, Healthcare Providers, and Clinic Staff. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Pretreated N = 458 | Treatment-Naïve N = 452 |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 275 (60.0%) | 267 (59.1%) |

| Female | 183 (40.0%) | 185 (40.9%) |

| Age at initial study visit [years], mean (SD) | 66.4 (11.7) | 66.3 (11.8) |

| Height [cm], mean (SD) | 171.0 (9.1) | 170.4 (9.3) |

| Weight [kg], mean (SD) | 86.1 (18.2) | 86.4 (17.1) |

| Most commonly reported diseases from medical history, n (%)a | ||

| Diabetes mellitus b | 456 (99.6%) | 452 (100.0%) |

| Arterial hypertension b | 236 (51.5%) | 238 (52.7%) |

| Hyperlipidemia b | 44 (9.6%) | 30 (6.6%) |

| Apoplexy | 20 (4.4%) | 26 (5.8%) |

| Myocardial infarct | 21 (4.6%) | 22 (4.9%) |

| Renal insufficiency b | 25 (5.5%) | 18 (4.0%) |

| Patients with diabetes mellitus: specification of type, n (%) | ||

| n | 456 | 452 |

| Type I | 50 (11.0%) | 46 (10.2%) |

| Type II | 358 (78.5%) | 347 (76.8%) |

| Unknown/Missingc | 48 (10.5%) | 59 (13.1%) |

| Diabetes mellitus: baseline HbA1c value | ||

| N | 189 | 184 |

| Mean (SD) [mmol/mol] | 51.7 (25.7) | 49.4 (26.1) |

| Mean (SD) [%] | 6.9 (2.4) | 6.7 (2.4) |

| Baseline BCVA examination of study eye | ||

| n | 446 | 443 |

| logMAR, mean (SD) | 0.374 (0.317) | 0.419 (0.310) |

| ETDRS letters, mean (SD) | 66.3 (15.9) | 64.1 (15.5) |

| Baseline OCT examination of study eye | ||

| Baseline OCT examination performed?, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 313 (68.3%) | 379 (83.8%) |

| No | 129 (28.2%) | 71 (15.7%) |

| Unknown/Missing c | 16 (3.5%) | 2 (0.4%) |

| Baseline OCT: central retinal thickness [µm] | ||

| n | 302 | 369 |

| Mean (SD) | 330.0 (108.1) | 352.8 (114.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haritoglou, C.; Iwersen, M.; Müller, B.; Beeke, E.; Berk, H.; Grüb, M.; Lorenz, K.; Scheffler, M.; Ziemssen, F., on behalf of the PACIFIC Study Group. Planned vs. Performed Treatment Regimens in Diabetic Macular Edema: Real-World Evidence from the PACIFIC Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093120

Haritoglou C, Iwersen M, Müller B, Beeke E, Berk H, Grüb M, Lorenz K, Scheffler M, Ziemssen F on behalf of the PACIFIC Study Group. Planned vs. Performed Treatment Regimens in Diabetic Macular Edema: Real-World Evidence from the PACIFIC Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093120

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaritoglou, Christos, Matthias Iwersen, Bettina Müller, Erik Beeke, Hüsnü Berk, Matthias Grüb, Katrin Lorenz, Martin Scheffler, and Focke Ziemssen on behalf of the PACIFIC Study Group. 2025. "Planned vs. Performed Treatment Regimens in Diabetic Macular Edema: Real-World Evidence from the PACIFIC Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093120

APA StyleHaritoglou, C., Iwersen, M., Müller, B., Beeke, E., Berk, H., Grüb, M., Lorenz, K., Scheffler, M., & Ziemssen, F., on behalf of the PACIFIC Study Group. (2025). Planned vs. Performed Treatment Regimens in Diabetic Macular Edema: Real-World Evidence from the PACIFIC Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 3120. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14093120