Compliance of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Basis

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Search Terms

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

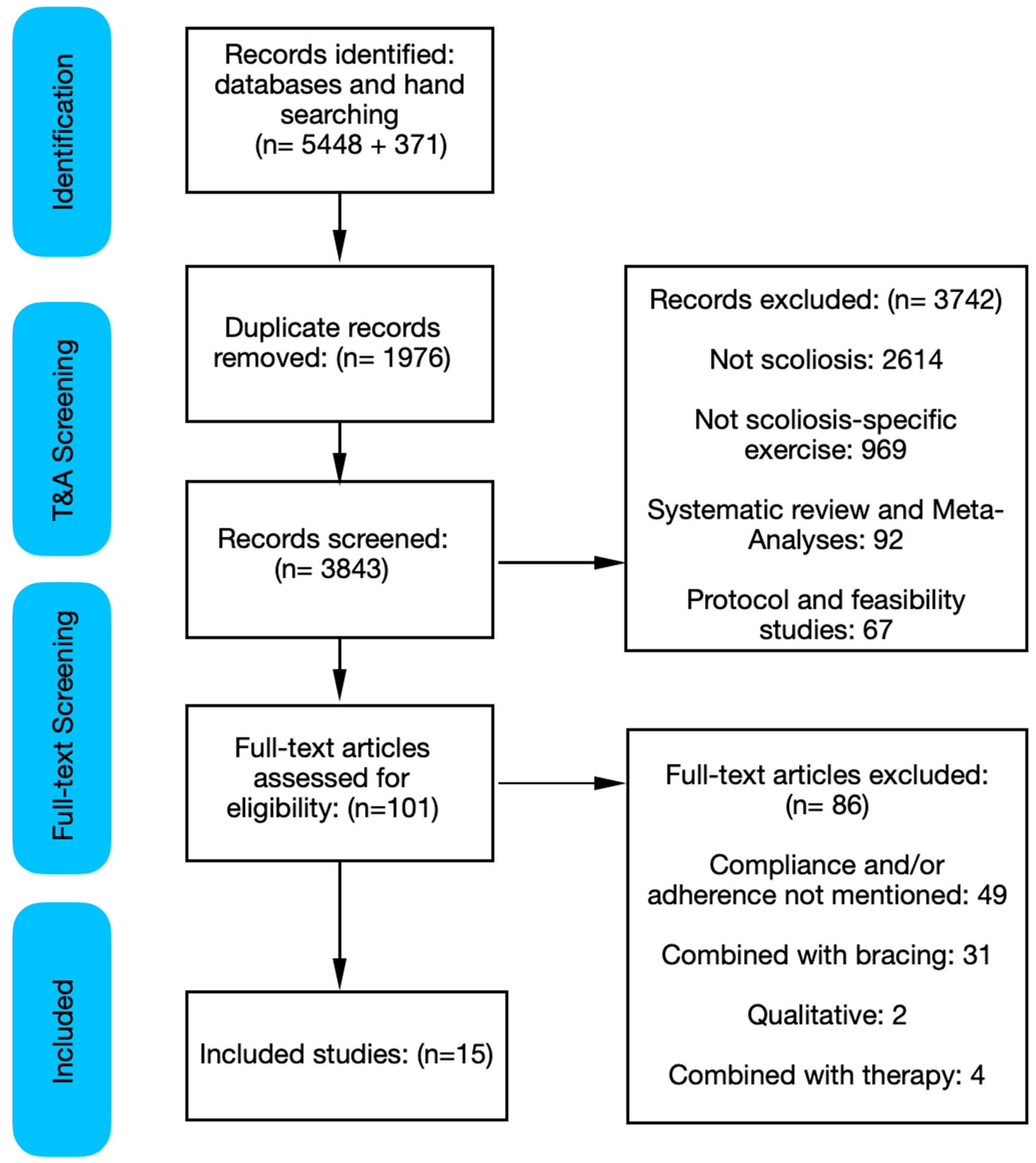

2.5. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.6. Quality Appraisal

2.7. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Compliance and Adherence Reporting

3.3. Motivational Strategy Reporting

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PubMed Search Strategy

References

- Simhon, M.E.; Fields, M.W.; Grimes, K.E.; Bakarania, P.; Matsumoto, H.; Boby, A.Z.; Berdishevsky, H.; Roye, B.D.; Roye, D.P., Jr.; Vitale, M.G. Completion of a formal physiotherapeutic scoliosis-specific exercise training program for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis increases patient compliance to home exercise programs. Spine Deform. 2021, 9, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quang, N.V.; Lawrence, H.L.; Edmond, H.M. Prediction of scoliosis progression using three-dimensional ultrasound images: A pilot study. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017, 12 (Suppl. S1), O10. [Google Scholar]

- Choon, S.L.; Chang, J.H.; Hyung, S.J.; Lee, D.-H.; Park, J.W.; Cho, J.J.; Yang, J.J.; Park, S. Association Between Vertebral Rotation Pattern and Curve Morphology in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. World Neurosurg. 2020, 143, e243–e252. [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny, M.R.; Senyurt, H.; Krauspe, R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child. Orthop. 2013, 7, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Aulisa, A.G.; Czaprowski, D.; Schreiber, S.; de Mauroy, C.; Diers, H.; Grivas, T.B.; Knott, P.; Kotwicki, T.; et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, S.; Parent, E.C.; Moez, E.K.; Hedden, D.M.; Hill, D.L.; Moreau, M.; Lou, E.; Watkins, E.M.; Southon, S.C. Schroth physiotherapeutic scoliosis-specific exercises added to the standard of care lead to better cobb angle outcomes in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis—An assessor and statistician blinded randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuru, T.; Yeldan, Ï.; Dereli, E.E.; Özdinçler, A.R.; Dikici, F.; Çolak, Ï. The efficacy of three-dimensional Schroth exercises in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A andomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticone, M.; Ambrosini, E.; Cazzaniga, D.; Rocca, B.; Ferrante, S. Active self-correction and task-oriented exercises reduce spinal deformity and improve quality of life in subjects with mild adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Results of a andomized controlled trial. Eur. Spine J. 2014, 23, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, R.; Du Plessis, J.; Pooke, T.; McAviney, J. The Improvement of Trunk Muscle Endurance in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis Treated with ScoliBrace® and the ScoliBalance® Exercise Approach. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, S.L.; Dolan, L.A.; Wright, J.G.; Dobbs, M.B. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükturan, Ö.; Kaya, M.H.; Alkan, H.; Büyükturan, B.; Erbahçeci, F. Comparison of the efficacy of Schroth and Lyon exercise treatment techniques in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled, assessor and statistician blinded study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2024, 72, 102952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufvenberg, M.; Diarbakerli, E.; Charalampidis, A.; Öberg, B.; Tropp, H.; Aspberg Ahl, A.; Möller, H.; Gerdhem, P.; Abbott, A. Six-Month Results on Treatment Adherence, Physical Activity, Spinal Appearance, Spinal Deformity, and Quality of Life in an Ongoing Randomised Trial on Conservative Treatment for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (CONTRAIS). J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; To, M.K.; Kuang, G.M.; Cheung, J.P.Y. The Relationship Between Compliance of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis Specific Exercises and Curve Regression With Mild to Moderate Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Glob. Spine J. 2024, 14, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Li, J.Y.; Shao, R.; Wu, T.X.; Wang, Y.Q.; Liu, X.G.; Yu, M. Schroth exercises improve health-related quality of life and radiographic parameters in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 134, 2589–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavidas, N.; Iakovidis, P.; Chatziprodromidou, I.; Lytras, D.; Kasimis, K.; Kyrkousis, A.; Apostolou, T. Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercises (PSSE-Schroth) can reduce the risk for progression during early growth in curves below 25°: Prospective control study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, H.; Bek, N.; Kaya, M.H.; Büyükturan, B.; Yetiş, M.; Büyükturan, Ö. The effectiveness of two different exercise approaches in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A single-blind, randomized-controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Xuan, X.; Yang, J.; Huang, Z. Effects of Specific Exercise Therapy on Adolescent Patients With Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Prospective Controlled Cohort Study. Spine 2020, 45, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.A.; Yousef, A.M. Impact of Schroth three-dimensional vs. proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 7717–7725. [Google Scholar]

- Negrini, S.; Zaina, F.; Romano, M.; Negrini, A.; Parzini, S. Specific exercises reduce brace prescription in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A prospective controlled cohort study with worst-case analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Negrini, A.; Parzini, S.; Romano, M.; Zaina, F. Specific exercises reduce the need for bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: A practical clinical trial. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tombak, K.; Yüksel, İ.; Ozsoy, U.; Yıldırım, Y.; Karaşin, S. A Comparison of the Effects of Supervised versus Home Schroth Exercise Programs with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Children 2024, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata, K.A.; Sucato, D.J.; Jo, C.H. Physical Therapy Scoliosis-Specific Exercises May Reduce Curve Progression in Mild Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Curves. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. Off. Publ. Sect. Pediatr. Am. Phys. Ther. Assoc. 2019, 31, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, K.A.; Dieckmann, R.J.; Hresko, M.T.; Sponseller, P.D.; Vitale, M.G.; Glassman, S.D.; Smith, B.G.; Jo, C.H.; Sucato, D.J. A United States multi-site randomized control trial of Schroth-based therapy in adolescents with mild idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2023, 11, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, T.H. Adherence Versus Compliance. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2023, 4, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Peñacoba, C.; Del Coso, J.; Leyton-Román, M.; Luque-Casado, A.; Gasque, P.; Fernández-Del-Olmo, M.Á.; Amado-Alonso, D. Key Factors Associated with Adherence to Physical Exercise in Patients with Chronic Diseases and Older Adults: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyake, K.; Suzuki, M.; Otaka, Y.; Momose, K.; Tanaka, S. Motivational Strategies for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Delphi Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, R.; Ilhan, E.; Pacey, V. How Schroth Therapists Vary the Implementation of Schroth Worldwide for Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Identifiers: First Author (year), Category (Sample Size) [Reference] | Parameters of Compliance or Adherence Defined and Reported | Section of the Paper Mentioning | Motivational Strategies | Factored into Results | Factored into Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Büyükturan et al. (2024), Compliance (n = 31) [12] | Supervised exercise sessions of 90 min each, three times a week for six months. If patient compliance was below 70%, precautions were taken. Home exercises consisted of stretching, posture training, breathing, and spinal flexibility exercises. Frequency and duration unclear. | Mentioned in the Materials and Methods section of the paper. | Not reported | Authors mentioned the study was completed with 100% attendance. No further information provided. | Not reported |

| Dufvenberg et al. (2021), Adherence (n = 135) [13] | A 4-point scale—from best “very sure” (1 point) to worst “not at all” (4 points)—was used to report adherence, motivation, and capability. The patient was asked to self-report adherence “the grade to which you feel that you have completed the treatment”. | The importance of adherence mentioned in the Methods. | Employed motivational strategies using the capability, opportunity, motivation, and behavior change model. | Not reported | Authors reported the level of participant adherence and compliance to treatment reflecting upon the outcomes of the treatment. |

| Fan et al. (2024), Compliance and Adherence (n = 763) [14] | Reported compliance. Described as 1 h private session a week, 1 h group session on weekends, and 45–60 min at home daily. | Reported in Materials and Methods under sub-section PSSE Protocol and Compliance. | Participants were auto-sent a checklist every two weeks gathering data about compliance, hours per day. Self-reported data. | Yes, reported in the results. Analysis shows the daily compliance and non-compliance. Scoliosis curve regression related to exercise compliance. | Yes, reported in the Discussion. Authors highlighted the impact on compliance and non-compliance on the outcomes reported in the Discussion. |

| Gao et al. (2021), Adherence (n = 64) [15] | Home exercise program adherence was set to two or three times per week for 1 h. Participants completed a 14-day intensive training during vacation time program supervised by certificated physical therapists. | Adherence mentioned in the Methods section under sub-headings Inclusion criteria “Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria of Schroth group” and “Schroth exercise treatment”. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Karavidas et al. (2024), Compliance and Adherence (n = 163) [16] | Every patient was advised to perform exercises at home 5 times per week, for 30 min. supervised sessions took place in our clinic once a week, for 55 min. Compliance was self-reported monthly using a scale from A to C (A = 5 d p/w, B = 3–4 d p/w, C = less than 2 d p/w). | Treatment protocol section under Materials and Methods | Not reported | Reported in the Results section. Compliance was good, having 78 subjects (47.9%) with excellent (A), 54 subjects (33.1%) with moderate (B), and 31 subjects (19%) with poor compliance (C). | Compliant patients had significantly less progression rate and brace prescription. Authors suggest it is attributed to the clearly described treatment protocol and to the regular supervised sessions and clinical follow-up, providing motivation. |

| Kocaman et al. (2021), Compliance (n = 28) [17] | Compliance is not clearly outlined. A vague statement about the study being completed with 100% compliance is mentioned. | Results—a brief mention of the study being completed with 100% compliance. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Kuru et al. (2016), Compliance (n = 45) [7] | Reported compliance. The parameters of what constitutes compliance was not defined; however, authors checked with caregivers whether the exercises were regularly performed. | Mentioned in the Methods section of the paper. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Liu et al. (2020), Compliance (n = 99) [18] | No parameters set for compliance. | A brief mention of compliance mentioned in the Discussion. Authors mention using the WeChat app to ask the number of hours per day participants exercised. | Authors highlight the use of a chat app to keep participants motivated. | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mohamed et al. (2021), Adherence (n = 34) [19] | Adherence is not clearly outlined. Attendance of treatment sessions was 98%, as mentioned in the Methods section of the intervention. | Methods—interventions | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Negrini et al. (2008), Compliance (n = 74) [20] | Compliance rate by dividing the number of exercise sessions performed by the expected frequency of two sessions per week. The patients continue treatment at a rehabilitation facility near their home (by themselves or with their parents) twice a week (40 min per session) plus one daily exercise at home (5 min). | Compliance is mentioned in the Material and Methods section. It is more specifically mentioned under the sub-heading “treatment” and under the sub-heading “outcome measures”. | Not reported | Reported in the Results section. Authors describe the percentage of compliance as 95%. | Discussion mentions analysis undertaken to determine compliance of greater than or equal to 30 min of exercise and 10 min or less as exercise curve progression. |

| Negrini et al. (2019), Adherence (n = 327) [21] | As part of home exercises for SEAS, an agenda set for adherence. Defined as 90 mins per week according to patient preferences. Therapist sessions set at four per year, once every three months. For usual physiotherapy group, adherence is assessed through self-reporting of participants and families. | Described in the Methods section of the paper. Protocol of intervention states adherence and parameters of adherence. | It is not apparent that strategies for improved adherence were employed. | Adherence of exercise is not reported. Rates of failure and dropout have been reported; however, it is unclear about rate of exercise adherence. | Participant adherence to exercise outlined in Discussion. Authors detail the number of minutes and standard deviation of participant adherence. |

| Simhon et al. (2021), Compliance (n = 81) [1] | HEP compliance, which was defned as performing ≥ 80 min of home exercises per week. Caregivers asked to recall number of minutes and days practised per week of home exercise program at four time points of interest: 1 week, 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years. | Mentioned in the Introduction as a factor for success of non-operative intervention. Also highlights the limitations of the published literature on tracking compliance of home exercise programs. | Not apparent if motivational strategies were used to motivate participant compliance. | Reported as the percentage of patients that were included in the study who were complaint with the defined parameters of compliance at each time point. | Discussed as the primary outcomes of the study. Details the mean number of minutes of home exercise compliance at the four different time points. |

| Tombak et al. (2024), Compliance (n = 37) [22] | Supervised exercise for one hour twice a week for twelve weeks. Participants in this group exercised at home for the remaining one hour five days a week. Another group home program consisted of unsupervised exercises for about 1 h every day for 12 weeks. Parameters were set to 83%. | Interventions under Materials and Methods section of the paper. | Home equipment and access to facilities were provided; it was made fun by technology support/video recording, and parent involvement was encouraged. | Exercise compliance performed with a physiotherapist was 100%, and home exercise compliance was 97.54%. In the home group (HSEG), compliance with the home program was 96.89%. | Not reported |

| Zapata et al. (2019), Compliance (n = 49) [23] | Compliance is not clearly outlined. The exclusion criteria list developmental disorders that prevent understanding and compliance with the exercise schedule. | Methods—listed as an exclusion criteria. Participants excluded if they have developmental disorder preventing exercise compliance. | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zapata et al. (2023), Adherence (n = 98) [24] | Home exercise program adherence was 15 min per day, 5 days a week (75 min per week) for 1 year. Patients also completed ≥ 8 h of one-on-one supervised PSSE for the first 6 months. | Adherence mentioned in the Methods section of the paper. Patients were given handouts of their HEP. Patients were sent an electronic weekly survey for 52 weeks using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) regarding HEP adherence. Under sub-heading outcomes, HEP adherence for the Exercise group (percentage of prescribed exercises completed from baseline to 6 months and 1-year follow-up). | A weekly two-question survey e-mail queried the total number of days and minutes patients performed their exercises. | Reported as a percentage of the best number of minutes per week. Results demonstrate HEP adherence was 81.6% ± 31.5% from baseline to 6 months and 62.8% ± 37.8% from baseline to 1-year follow up. | Factored into Discussion, highlighting the rate of dropout from the exercise group. Participants preferred electronic data gathering on adherence using REDCap over paperlog. Insights offered by authors about the barriers and challenges with exercise adherence. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fazalbhoy, A.; McAviney, J.; Mirenzi, R. Compliance of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092950

Fazalbhoy A, McAviney J, Mirenzi R. Compliance of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(9):2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092950

Chicago/Turabian StyleFazalbhoy, Azharuddin, Jeb McAviney, and Rosemary Mirenzi. 2025. "Compliance of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 9: 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092950

APA StyleFazalbhoy, A., McAviney, J., & Mirenzi, R. (2025). Compliance of Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercise in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(9), 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14092950