Relationship Between Vertigo and Consumption of Psychotropic Drugs: A Prospective Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Inclusion Criterion

- Two or more spontaneous episodes of vertigo, each lasting 20 min to 12 h.

- Audiometrically documented low- to medium-frequency sensorineural hearing loss in one ear, defining the affected ear on at least one occasion before, during, or after one of the episodes of vertigo.

- Fluctuating aural symptoms (hearing, tinnitus, or fullness) in the affected ear.

- Not better accounted for by another vestibular diagnosis.

- At least 5 episodes with vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity, lasting 5 min to 72 h.

- Current or previous history of migraine with or without aura according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3).

- One or more migraine features with at least 50% of the vestibular episodes:

- ○

- Headache with at least two of the following characteristics: one-sided location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, aggravation by routine physical activity.

- ○

- Photophobia and phonophobia.

- ○

- Visual aura.

- Not better accounted for by another vestibular or ICHD diagnosis.

- Recurrent attacks of positional vertigo or positional dizziness provoked by lying down or turning over in the supine position.

- Duration of attacks < 1 min.

- Positional nystagmus elicited after a latency of one or few seconds by the Dix–Hallpike maneuver, the side-lying maneuver (Semont diagnostic maneuver), or the supine roll test.

- Not attributable to another disorder.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Age < 18 years old;

- Simultaneous diagnosis of two or more types of vertigo;

- Other causes of vestibular symptoms (including other central vestibular disorders besides VM) different from those mentioned above in the Inclusion Criterion section;

- Severe cognitive impairment that prevents providing informed consent.

2.4. Control Group

2.5. Methodology

- Age at the time of this study;

- Sex;

- Age at onset;

- The subtypes of BPPV and their locations (side and canal affected);

- The side distribution in MD;

- The side and the branch of the vestibular nerve affected in VN;

- History of psychiatric diseases;

- Psychotropic drugs regularly consumed (≥1 month, while sporadic or unscheduled consumption was excluded), by reviewing the electronic medical record and directly asking the participants about their consumption. The number of different drugs consumed by each patient was recorded. Drugs were grouped into the following categories, applying the Anatomical, Therapeutic, Chemical Classification System (ATC code):

- Anxiolytics (N05B) (e.g., diazepam, alprazolam, bromazepam, lorazepam, clorazepate, ketazolam) and hypnotics and sedatives (N05C) group (e.g., lormetazepam, zolpidem);

- Antidepressant (N06A) group (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline, clomipramine, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, escitalopram, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, mirtazapine, trazodone, duloxetine, reboxetine);

- Antiepileptic (N03A) group (e.g., pregabalin, gabapentin, sodium valproate);

- Antipsychotic (N05A) group (e.g., quetiapine, olanzapine, clozapine, aripiprazole, paliperidone, tiapride).

2.6. Sample Size Estimation

2.7. Sample

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MD | Ménière’s disease |

| VM | Vestibular migraine |

| VN | Vestibular neuritis |

| BPPV | Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo |

References

- Soto-Varela, A.; Huertas-Pardo, B.; Gayoso-Diz, P.; Santos-Perez, S.; Sanchez-Sellero, I. Disability perception in Menière’s disease: When, how much and why? Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, J.; Manzari, L.; Figueroa, J.J.; Castillo-Bustamante, M. Understanding Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) and Its Impact on Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e63039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batinović, F.; Sunara, D.; Košta, V.; Pernat, M.; Mastelić, T.; Paladin, I.; Pleić, N.; Krstulović, J.; Đogaš, Z. Psychiatric Comorbidities and Quality of Life in Patients with Vestibular Migraine and Migraine without Vertigo: A Cross-Sectional Study from a Tertiary Clinic. Audiol. Res. 2024, 14, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Xia, Y.; Luo, Q.; Li, Q.; Jiang, H.; Xiong, Y. Psychological Distress and Meniere’s Disease: A Bidirectional Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2024, 170, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subasi, B.; Yildirim, N.; Akbey, Z.Y.; Karaman, N.E.; Arik, O. Correlations of Clinical and Audio-Vestibulometric Findings with Coexisting Anxiety and Depression in Ménière’s Disease Patients. Audiol. Neurootol. 2023, 28, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiji, M.R.; Akbarpour, M.; Soleimani, R.; Asli, R.H.; Leyli, E.K.; Saberi, A.; Akbari, M.; Ramezani, H.; Nemati, S. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in Meniere’s disease; a comparative analytical study. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearn, D.J.; Umapathy, D. Vestibular impairment in older people frequently contributes to dizziness as part of a geriatric syndrome. Clin. Med. 2015, 15, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancello, V.; Hatzopoulos, S.; Santopietro, G.; Fancello, G.; Palma, S.; Skarżyński, P.H.; Bianchini, C.; Ciorba, A. Vertigo in the Elderly: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmann, C.; Dieterich, M.; Becker-Bense, S.; Schmid-Mühlbauer, G. Bilateral vestibulopathy—Loss of vestibular function and experience of emotions. J. Psychosom. Res. 2024, 186, 111894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, N.L.; White, M.P.; Ronan, N.; Whinney, D.J.; Curnow, A.; Tyrrell, J. Stress and Unusual Events Exacerbate Symptoms in Menière’s Disease: A Longitudinal Study. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Best, C.; Bense, S.; Breuer, P.; Diener, G.; Tschan, R.; Dieterich, M. Psychiatric comorbidity in different organic vertigo syndromes. J. Neurol. 2008, 255, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni-Dargah, M.; Falahati, Z.; Pastras, C.; Khajeh, K.; Mukherjee, P.; Razmjou, A.; Stefani, S.; Asadnia, M. Meniere’s disease: Pathogenesis, treatments, and emerging approaches for an idiopathic bioenvironmental disorder. Environ. Res. 2023, 238, 116972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahnoor, S.; Habiba, U.; Shah, H.H. Do benzodiazepines have a future in treating acute vertigo. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 82, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, N.; Gubbels, S.P.; Schwartz, S.R.; Edlow, J.A.; El-Kashlan, H.; Fife, T.; Holmberg, J.M.; Mahoney, K.; Hollingsworth, D.B.; Roberts, R.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (Update). Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2017, 156 (Suppl. 3), S1–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisdorff, A.R. Management of vestibular migraine. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2011, 4, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanandrea, L.; Colombo, B.; Filippi, M. Vestibular Migraine Therapy: Update and Recent Literature Review. Audiol. Res. 2023, 13, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolberg, C.; Roberts, R.A.; Watford, K.E.; Picou, E.M.; Corcoran, K. Long-Term Effects of Intervention on Vestibular Migraine: A Preliminary Study. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2024, 133, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.; Gioacchini, F.M.; Astorina, A.; Pisani, D.; Scarpa, A.; Marcianò, G.; Casarella, A.; Basile, E.; Rania, V.; Re, M.; et al. The pharmacological treatment of acute vestibular syndrome. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 999112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Carey, J.; Chung, W.-H.; Goebel, J.A.; Magnusson, M.; Mandalà, M.; Newman-Toker, D.E.; Strupp, M.; Suzuki, M.; Trabalzini, F.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for Menière’s disease. J. Vestib. Res. 2015, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Newman-Toker, D. Vestibular migraine: Diagnostic criteria. J. Vestib. Res. 2012, 22, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Kheradmand, A.; et al. Vestibular migraine: Diagnostic criteria (Update). J. Vestib. Res. 2022, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Brevern, M.; Bertholon, P.; Brandt, T.; Fife, T.; Imai, T.; Nuti, D.; Newman-Toker, D. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: Diagnostic criteria. J. Vestib. Res. 2015, 25, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staab, J.P.; Eckhardt-Henn, A.; Horii, A.; Jacob, R.; Strupp, M.; Brandt, T.; Bronstein, A. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J. Vestib. Res. 2017, 27, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkirov, S.; Stone, J.; Holle-Lee, D. Treatment of Persistent Postural-Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) and Related Disorders. Curr. Treat. Opt. Neurol. 2018, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sellero, I.; San-Román-Rodríguez, E.; Santos-Pérez, S.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Soto-Varela, A. Caffeine intake and Menière’s disease: Is there relationship? Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sellero, I.; San-Román-Rodríguez, E.; Santos-Pérez, S.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Soto-Varela, A. Alcohol consumption in Menière’s disease patients. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkov, R.; Strobl, R.; Heinlin, N.; Krause, E.; Olzowy, B.; Koppe, C.; Grill, E. Atmospheric Pressure and Onset of Episodes of Menière’s Disease—A Repeated Measures Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sellero, I.; Soto-Varela, A. Relationship Between Occupational Exposure to Noise and Vibrations and Vertigo: A Prospective Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnosis | MD | VM | VN | BPPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 232 | 79 | 34 | 161 |

| Female/Male | 139/93 | 60/19 | 24/10 | 118/43 |

| Age (years) | 60.2 ± 12.149 | 45.7 ± 13.344 | 55.9 ± 14.649 | 63.9 ± 14.964 |

| Side | Right: 98 Left: 81 Bilateral: 53 | Right: 14 Left: 20 | Right: 80 Left: 65 Bilateral: 16 | |

| Canal | Posterior: 123 Lateral: 18 —Canalithiasis: 6 —Cupulolithiasis: 12 Superior: 9 Multi-canal: 11 | |||

| Vestibular nerve | Superior: 22 Inferior: 4 Both: 8 |

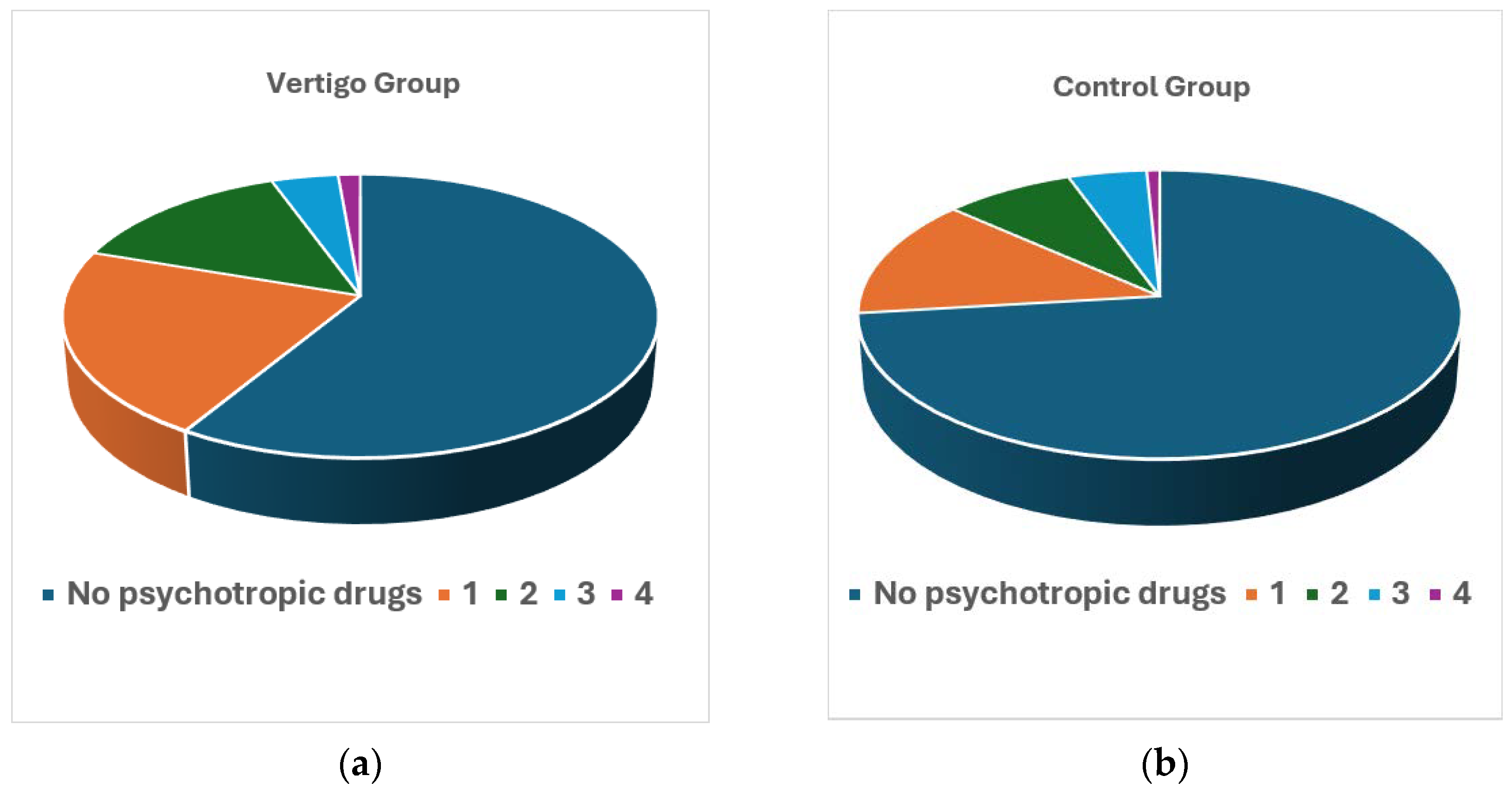

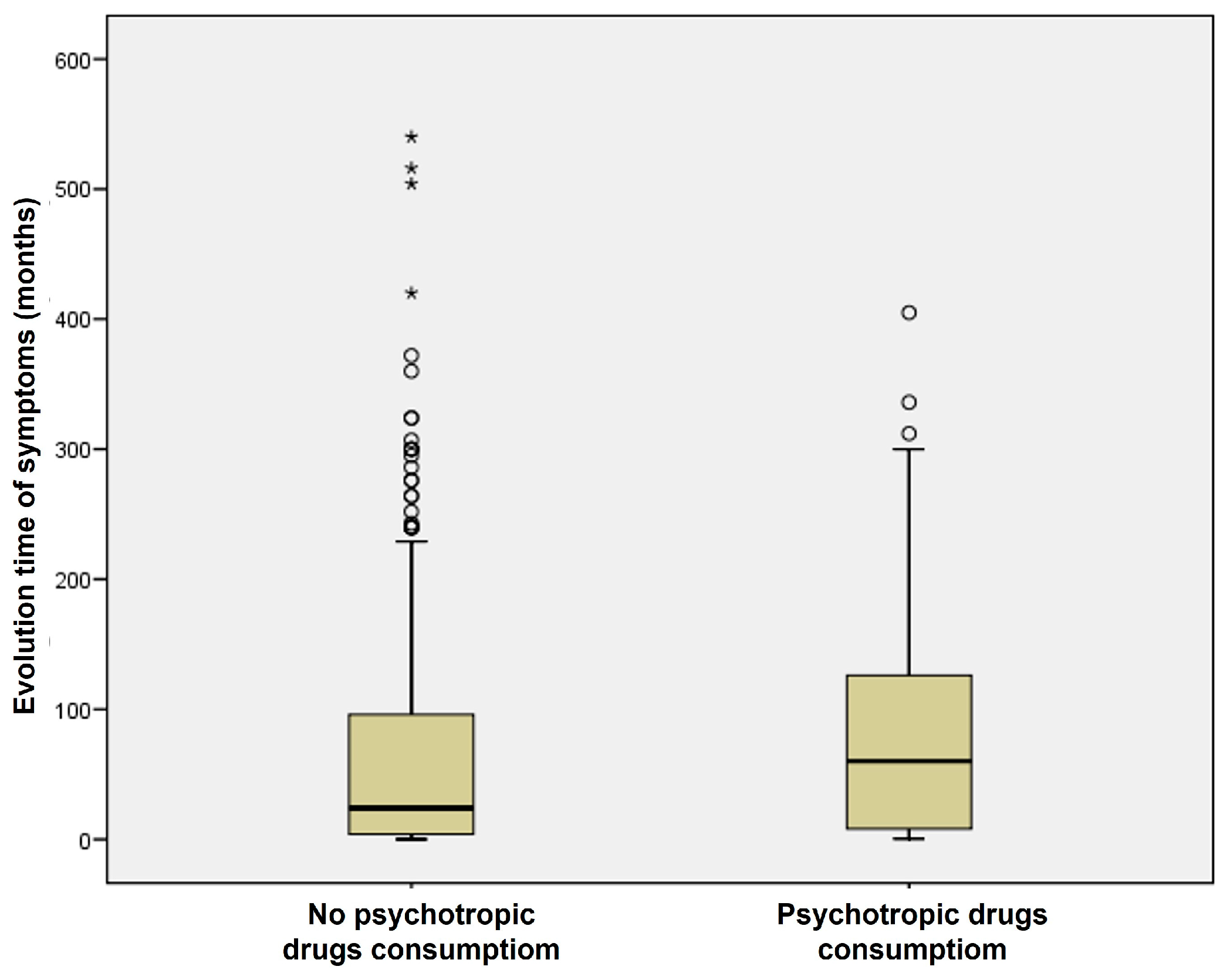

| Number of Psychotropic Drugs Consumed | Patients with Vertigo (%) | Individuals of the Control Group (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21.54 | 13.44 |

| 2 | 14.23 | 7.91 |

| 3 | 4.15 | 4.74 |

| 4 | 1.38 | 0.79 |

| ≥1 | 41.30 | 26.88 |

| Psychotropic Drugs | Patients with Vertigo (%) | Individuals of the Control Group (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives (alone) (A + AA) | 74 + 4 = 78 (15.42%) | 21 A + 3 AA = 24 (9.48%) |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives (in association) (AB + AAB + ABB + A * + A ** + A ***) | 54 + 9 + 9 + 2 + 3 + 7 = 84 (16.60%) | 16 + 3 + 5 + 0 + 2 + 2 = 28 (11.07%) |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives (alone or in association) | 162 (32.02%) | 52 (20.55%) |

| Antidepressants (alone) (B + BB) | 28 + 4 = 32 (6.32%) | 12 + 0 = 12 (4.74%) |

| Antidepressants (in association) (AB + AAB + ABB + B * + B ** + B ***) | 54 + 9 + 9 + 6 + 3 + 7 = 88 (17.39%) | 16 + 3 + 5 + 1 + 3 + 2 = 30 (11.86%) |

| Antidepressants (alone or in association) | 120 (23.72%) | 42 (16.60%) |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives + antidepressants (alone) (AB + AAB + ABB + AABB + ABBB) | 54 + 9 + 9 + 3 + 0 = 75 (14.82%) | 16 + 3 + 5 + 1 + 1 = 26 (10.28%) |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives + antidepressants (in association) (AB * + AB **) | 3 + 4 = 7 (1.38%) | 1 + 0 = 1 (0.39%) |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives + antidepressants (alone or in association) | 82 (16.21%) | 27 (10.67%) |

| Antiepileptics (alone) (C + CC) | 7 + 1 = 8 (1.58%) | 1 + 0 = 1 (0.40%) |

| Antiepileptics (in association) (C * + C ** + C ***) | 7 + 1+ 2 = 10 (1.98%) | 0 + 2 + 0 = 2 (0.79%) |

| Antiepileptics (alone or in association) | 18 (3.56%) | 3 (1.19%) |

| Antipsychotics (in association) (D * + D ** + D ***) | 3 + 2 + 2 = 7 (1.38%) | 1 + 2 + 0 = 3 (1.19%) |

| Psychotropic Drugs | Patients with Vertigo (%) | Individuals of the Control Group (%) | Chi-Square (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives (alone) | 15.42 | 9.48 | 0.0005 |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives (alone or in association) | 32.02 | 20.55 | 0.001 |

| Antidepressants (alone) | 6.32 | 4.74 | 0.0005 |

| Antidepressants (alone or in association) | 23.72 | 16.60 | 0.0004 |

| Anxiolytics and hypnotics and sedatives + antidepressants (alone or in association) | 16.21 | 10.67 | 0.001 |

| Antiepileptics (alone or in association) | 3.56 | 1.19 | 0.0003 |

| Antipsychotics (in association) | 1.38 | 1.19 | 0.0005 |

| Consumption | MD (%) | VM (%) | VN (%) | BPPV (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No psychotropic drug consumption | 135 (58.19) | 45 (56.96) | 23 (67.65) | 94 (58.39) | 297 |

| Psychotropic drug consumption | 97 (41.81) | 34 (43.04) | 11 (32.35) | 67 (41.61) | 209 |

| Patients | 232 | 79 | 34 | 161 | 506 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Sellero, I.; Soto-Varela, A. Relationship Between Vertigo and Consumption of Psychotropic Drugs: A Prospective Case–Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082555

Sánchez-Sellero I, Soto-Varela A. Relationship Between Vertigo and Consumption of Psychotropic Drugs: A Prospective Case–Control Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(8):2555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082555

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Sellero, Inés, and Andrés Soto-Varela. 2025. "Relationship Between Vertigo and Consumption of Psychotropic Drugs: A Prospective Case–Control Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 8: 2555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082555

APA StyleSánchez-Sellero, I., & Soto-Varela, A. (2025). Relationship Between Vertigo and Consumption of Psychotropic Drugs: A Prospective Case–Control Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(8), 2555. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14082555