Abstract

Objective: Tolerance to the acute effects of alcohol, i.e., feeling less intoxicated after consuming the same amount of alcohol, has been reported for individuals who regularly consume alcohol. In this study, it was investigated whether such tolerance also exists for experiencing the alcohol hangover. Methods: Data from five studies that assessed hangover frequency and hangover severity were combined (n = 924). Partial correlations were computed between hangover frequency and hangover severity, with age, sex, and weekly alcohol consumption as possible confounders. Results: A significant and positive correlation was found between hangover frequency and hangover severity (r = 0.692, p < 0.001). After correcting for sex, age, and weekly alcohol consumption, the partial correlation remained significant (r = 0.526, p < 0.001). Conclusions: The observed positive association between hangover frequency and hangover severity suggests a reverse tolerance: if hangovers are experienced more frequently, they are more severe.

1. Introduction

The alcohol hangover is referred to as the combination of negative mental and physical symptoms which can be experienced after a single episode of alcohol consumption, starting when blood alcohol concentration (BAC) approaches zero [1]. The hangover state is characterized by a plethora of symptoms, including fatigue, headache, and nausea, that can have a negative impact on mood and physical well-being [2] and negatively influence daily activities, such as driving a car [3], riding a bicycle [4], or job performance [5,6,7].

The economic costs of hangovers for the Dutch economy in terms of absenteeism (i.e., days not worked due to hangover) and presenteeism (i.e., being 24.9% less productive on average on hangover days) were estimated at EUR 2.7 billion for 2019 [7]. In addition to economic costs, the alcohol hangover is a serious public health concern. Frequently experiencing hangovers makes individuals more susceptible to developing depression [8,9], ischemic stroke [10], and cardiovascular disease [11]. In addition, it has been hypothesized that frequently experiencing hangovers predisposes individuals to developing alcohol use disorder in the future [12,13,14].

It remains an unanswered question whether the relationship between hangover frequency and hangover severity is positive or negative. That is, do hangovers become worse when you experience them more frequently (i.e., reverse tolerance), or do they become less severe because you get used to the amount of alcohol consumed (i.e., tolerance)?

Schuckit and colleagues published extensively on the development of tolerance to acute alcohol effects. Drinkers who start to score lower on the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) Scale need to consume more alcohol to reach the same intoxication effect as they previously experienced [15,16,17,18,19]. Extrapolating the concept of tolerance seen for acute alcohol effects to the alcohol hangover, it could be hypothesized that when experiencing hangovers more frequently, after consuming the same amount of alcohol, these hangovers would become less severe (i.e., tolerance), thereby potentially fostering a further escalation of alcohol consumption.

Alternatively, reverse tolerance could develop when hangovers are experienced more frequently. Išerić et al. [20] recently discussed the hypothesis that with more frequent hangovers, the chances of developing chronic systemic inflammation increase. Systemic inflammation has been linked to poorer health and increased susceptibility to developing chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. This condition may also increase the likelihood of experiencing hangovers, and due to the reduced immune fitness, the severity of these hangovers may increase. As a result, a positive association between hangover frequency and hangover severity would be expected: more severe hangovers when they are experienced more frequently.

Only a few studies have evaluated the relationship between hangover frequency and hangover severity. In an experimental study in 90 social drinkers, Köchling et al. [21] found no significant correlation between hangover frequency and reported hangover severity after administering alcohol to reach a BAC of 0.12%. However, for the correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity, this study used a categorical measure of hangover frequency (‘rarely’, ‘once monthly’, ‘more than once monthly, and less than once weekly’, ‘once weekly’, and ‘more than once weekly’) and an unvalidated composite symptom severity score. The latter may explain the absence of a significant correlation. Verster et al. [22] summarized assessments of three studies relating hangover frequency to hangover severity. The first survey study among 791 Dutch students [23] related hangover frequency to the severity of the past month’s most recent hangover occasion. Hangover severity was assessed via three different validated composite hangover symptom severity scales, the Hangover Severity Scale [24], the Acute Hangover Scale [25], and the Hangover Symptom Severity Scale [23]. A significant positive correlation was found for each severity scale (r = 0.145 to r = 0.198, p < 0.001), which remained significant after correcting for the amount of alcohol consumed. The second survey among 333 international young adults on holiday or working in Fiji [26] related hangover frequency to the past three days’ average hangover severity. A significant positive partial correlation, corrected for the estimated BAC, was found between hangover frequency and hangover severity (r = 0.276, p < 0.001). The third study was a naturalistic study [27], in which 99 Dutch students consumed alcohol freely at a venue of choice. The next day hangover severity was assessed with the HSS and a single-item rating scale, ranging from absent (score 0) to extreme (score 10) [28]. Again, significant correlations were found between the hangover frequency and hangover severity, assessed with the Hangover Severity Scale (r = 0.452, p < 0.001) and the single-item hangover scale (r = 0.529, p < 0.001). The correlations remained significant after correcting for the estimated BAC (HSS: r = 0.301, p = 0.004, single-item: r = 0.297, p = 0.004).

Except for Köchling et al. [21], all other studies reported a significant positive correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity. There are, however, some limitations to these studies. First, all studies except the research conducted in Fiji [26] assessed hangover severity for a single drinking occasion. The latter is a disadvantage of the study methodology, as a single drinking occasion does not necessarily reflect the average hangover severity these individuals experience and is therefore not necessarily representative. For the individual drinker, hangover severity can vary between drinking occasions. For example, Köchling et al. [21] reported that there was a significant within-subject variation in hangover severity in their study: about 20% of the sample reported very different hangover severity ratings on each test day, despite the fact that an equal amount alcohol was consumed on the assessed occasions [29]. Therefore, it is more accurate to access an average hangover severity score corresponding to multiple hangover occasions, than assessing hangover severity at a random single hangover occasion. Secondly, all studies except for Fuit et al. [27] assessed hangover severity with different composite symptom scales. As each of these scales include different symptoms, it is unlikely that the sum score accurately reflects the overall hangover severity [28]. To determine the relationship between hangover frequency and hangover severity more accurately, we combined data from five studies that assessed both hangover frequency and the average hangover severity, all using the preferrable single-item hangover severity scale [28]. The objective of the current study was to evaluate the relationship between hangover frequency and average hangover severity.

2. Materials and Methods

A literature search (PubMed and cross references) was conducted with the key words ‘hangover frequency’ and ‘hangover severity’ to identify studies that assessed both hangover frequency and average hangover severity. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. The search retrieved n = 40 publications. N = 35 publications were excluded as they did not include assessments of both hangover frequency and average hangover severity. Data from five studies were included and combined into one dataset [30,31,32,33,34]. The study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The first study comprised a survey among 557 Dutch students [30]. The second study comprised a survey among 341 Dutch students, PhD students and post-docs [31]. The third study comprised a survey among 108 Dutch students [32]. The fourth study was a survey among 317 young adults living in Germany [33]. The fifth study comprised a study among 161 Dutch students [34].

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

All studies assessed hangover frequency by asking ‘How many hangovers did you experience per month?’ and the corresponding hangover severity was assessed with a single-item scale, ranging from 0 (absent) to 10 (extreme) [28]. Age (years), sex (male or female), and average weekly alcohol consumption in standard units were also recorded.

The statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Mean and standard deviation were computed for each variable. Normality was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. The hangover severity and frequency data are not normally distributed (p < 0.001). Therefore, nonparametric statistical tests were used to analyze the data. Sex differences were evaluated with the Independent Samples Mann–Whitney U Test. Differences between males and females were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Spearman’s correlation was computed between hangover frequency and hangover severity. In addition, a nonparametric Spearman’s partial correlation [35,36] correcting for age, sex, and weekly alcohol consumption was computed. Finally, nonparametric Spearman’s partial correlations between age and hangover frequency as well as severity were computed, correcting for the amount of weekly alcohol consumption. Correlations were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. The analyses were conducted for the combined sample and for males and females separately.

3. Results

Of the total n = 1484 participants, n = 924 reported to consume alcohol and provided data on their hangover frequency and average severity. Their mean (SD) age was 21.8 (3.6) years old, and 27.9% of the samples were male. They consumed on average 7.6 (9.0) alcoholic drinks per week, and reported 1.4 (2.1) hangovers per month, with an average hangover severity rating of 3.2 (2.7). A comparison of these outcome variables between males and females is summarized in Table 2. Males consumed significantly more alcohol per week and reported significantly more hangovers. No significant sex difference was found for hangover severity, and although statistically significant, the age difference between the sexes was neglectable (i.e., less than 2 months on average).

Table 2.

Study outcomes.

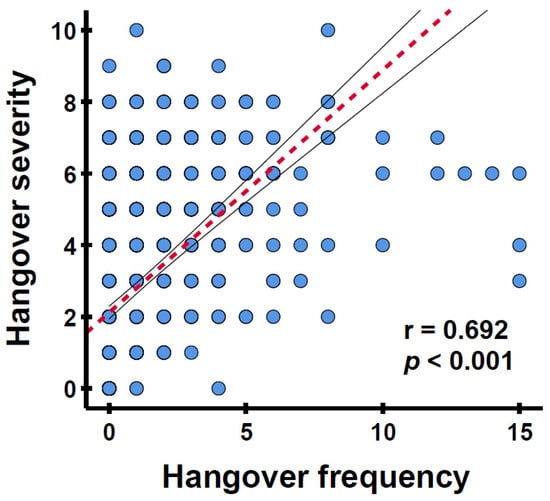

For the individual studies, all correlations between hangover frequency and hangover severity were statistically significant (Refs. [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]: r = 0.624, r = 0.824, r = 0.828, r = 0.853, and r = 0.850, respectively, all p < 0.001). For the combined sample, the correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity, as depicted in Figure 1, was positive and significant (r = 0.692, p < 0.001). After correcting for sex, age, and weekly alcohol consumption, the partial correlation remained significant (r = 0.526, p < 0.001). The correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity was significant for both males (n = 269, r = 0.729, p < 0.001) and females (n = 681, r = 0.674, p < 0.001) and remained significant after correcting for age and weekly alcohol consumption (r = 0.617, p < 0.001 and r = 0.487, p < 0.001, respectively).

Figure 1.

The relationship between hangover frequency and average hangover severity. Hangover frequency was assessed as occasions per month; hangover severity was rated on a scale ranging from 0 (absent) to 10 (extreme). The red striped line represents Spearman’s correlation. The black lines indicate the 95% confidence interval.

Finally, nonparametric partial correlations, correcting for weekly alcohol consumption, were computed between age and hangover frequency and hangover severity. The correlations between age and hangover frequency (r = 0.071, p = 0.029) and between age and hangover severity (r = −0.002, p = 0.946) were not statistically significant. For males and females separately, the correlations of age with hangover frequency and hangover severity did not reach statistical significance.

4. Discussion

The analyses showed a significant and positive correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity. This finding was observed for both the individual studies and the combined sample, for males and females separately, and remained significant after correcting for age, sex, and weekly alcohol consumption. This consistent observation of a positive association between hangover frequency and hangover severity suggests the development of a reverse tolerance, i.e., when hangovers are experienced more frequently, they tend to be worse.

The observation of a reverse tolerance is opposite to the effects seen for the acute effects of alcohol, where tolerance may develop when alcohol is consumed more frequently [15,16,17,18,19]. The findings are in line with the hypothesis of Išerić et al. [20], that the development of systemic inflammation and the corresponding reduced immune fitness may exaggerate hangover severity, as the hangover is elicited by an inflammatory response to alcohol consumption [37] that may be greater in individuals who (already) have elevated immune biomarker levels due to frequently drinking alcohol and/or experiencing hangovers [20]. Future prospective studies assessing biomarkers of immune functioning should confirm this hypothesis.

Strengths of this study comprise its large, combined sample size and the fact that we corrected the correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity for age, sex, and weekly alcohol consumption. The latter is important, as previous research has shown that on average both alcohol consumption as well as hangover frequency and severity decrease when growing older [38,39,40]. In addition, sex differences have been reported, showing a greater hangover frequency and severity in males compared to females [40]. However, these sex differences may be caused by the greater alcohol intake of males compared to females, and other research suggested that sex differences are no longer significant after correcting for alcohol intake [41]. Indeed, research showed that for both males and females, hangover frequency and severity increase with greater alcohol intake [42]. A second strength of this study was the use of a single-item overall assessment of hangover severity, which is considered more accurate than composite symptom scores [28].

A limitation of this study includes the fact that there are several other factors that might influence overall alcohol consumption and, in particular, hangover frequency and/or hangover severity that were not taken into account, since these were not (consistently) measured across the studies. These include, but are not limited to, lifestyle factors such as sleep [43], daily diet [44], physical activity [45], smoking and drug use [27,46], congener content of the consumed drinks [43,47], estimated BAC [26], subjective intoxication while drinking [26,48,49], mood while drinking [26], race and ethnicity [50,51], genetic predisposition [50,52,53], and familial risk for alcoholism [54,55,56,57]. Future research should take these factors into account. A second limitation of the current work is the fact that all survey data were collected retrospectively. This could have introduced recall bias among participants. It is therefore important that future prospective, longitudinal studies including real-time momentary assessments confirm our findings. It may also be interesting to further investigate other characteristics of the hangover episode, such as its duration related to the global single-item hangover severity scores. Third, data from different studies were combined for the presented analysis. This may introduce heterogeneity, as the studies were conducted in different countries, used different recruitment strategies, and included different age groups and participants (e.g., students versus the general adult population). This was however performed on purpose, as it was aimed at creating a diverse sample. Of importance, the assessments of hangover frequency and hangover severity were identical across all studies. Fourth, all studies were cross-sectional, and correlational analyses were conducted. In theory, correlations can be interpreted bi-directionally. However, as it is unlikely that experiencing more severe hangovers will lead to having hangovers more frequently, we interpret the study outcome that more frequently experiencing hangovers is associated with having more severe hangovers. Fifth, data from five individual studies were combined into one dataset. Therefore, there is a potential risk that heterogeneity between the studies has influenced the overall outcome. However, there are several factors that reduce or eliminate this impact. Of importance in this context is the fact that each study assessed hangover frequency and severity in the same way. Further, the correlations between hangover frequency and hangover severity of the individual studies were highly comparable with each other and the overall analysis. Sixth, while the study outcomes are clear, the correlational analyses do not provide biological evidence for the causes of the observed relationship between hangover frequency and hangover severity. Išerić et al. [20] suggested that with more frequent hangovers, the chances of developing chronic systemic inflammation increase. To prove this hypothesis, future longitudinal studies should be conducted, including the assessment of biomarkers of immune functioning. A final limitation of the current sample is the age range from 17 to 44 years. Although this is the age range at which hangovers are most frequently experienced [39], future research should also investigate the alcohol hangover in older age groups.

5. Conclusions

Notwithstanding the limitations discussed above, the data show a significant and strong positive correlation between hangover frequency and hangover severity. The observation of a reverse tolerance deserves more attention by researchers and policymakers, as frequently experiencing hangovers has a significant impact on the susceptibility to develop chronic systemic inflammation and related immune-related diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., E.I., M.N.Z., A.-K.S. and J.C.V.; statistical analysis, J.C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R. and J.C.V.; writing—review and editing, S.R., E.I., M.N.Z., A.-K.S. and J.C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as this is a secondary analysis of existing data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Over the past 3 years, J.C.V. has received research support from Danone and Inbiose and acted as a consultant/advisor for Eisai, KNMP, Med Solutions, Mozand, Red Bull, Sen-Jam Pharmaceutical, and Toast! J.C.V. owns stock from Sen-Jam Pharmaceutical. J.C.V., E.I., M.N.Z. and S.R. received travel support from Sen-Jam Pharmaceutical. A-K.S. has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BAC | Blood alcohol concentration |

| SRE | Self-rating of the effects of alcohol |

References

- Verster, J.C.; Scholey, A.; van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Benson, S.; Stock, A.-K. Updating the definition of the alcohol hangover. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackus, M.; Van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Van Neer, R.H.P.; Vermeulen, S.A.; Terpstra, C.; Brookhuis, K.A.; Garssen, J.; Scholey, A.; Verster, J.C. Differences in next-day adverse effects and impact on mood of an evening of heavy alcohol consumption between hangover-sensitive drinkers and hangover-resistant drinkers. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verster, J.C.; Bervoets, A.C.; de Klerk, S.; Vreman, R.A.; Olivier, B.; Roth, T.; Brookhuis, K.A. Effects of alcohol hangover on simulated highway driving performance. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 2999–3008. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung, B.; Schwender, H.; Mindiashvili, N.; Ritz-Timme, S.; Malczyk, A.; Daldrup, T. The effect of alcohol hangover on the ability to ride a bicycle. Int. J. Legal Med. 2015, 129, 751–758. [Google Scholar]

- Frone, M.R. Prevalence and distribution of alcohol use and impairment in the workplace: A U.S. national survey. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006, 67, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde, H.; Christophersen, A.S.; Moan, I.S.; Yttredal, B.; Walsh, J.M.; Normann, P.T.; Mørland, J. Use of alcohol and drugs by Norwegian employees: A pilot study using questionnaires and analysis of oral fluid. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2010, 5, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Severeijns, N.R.; Sips, A.S.M.; Merlo, A.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. Absenteeism, presenteeism, and reduced productivity due to alcohol hangover and associated costs for the Dutch economy. Healthcare 2024, 12, 335. [Google Scholar]

- Paljärvi, T.; Koskenvuo, M.; Poikolainen, K.; Kauhanen, J.; Sillanmäki, L.; Mäkelä, P. Binge drinking and depressive symptoms: A 5-year population-based cohort study. Addiction 2009, 104, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki, T.M.; Trela, C.J.; Mermelstein, R.J. Hangover symptoms, heavy episodic drinking, and depression in young adults: A cross-lagged analysis. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 78, 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Rantakömi, S.H.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Sivenius, J.; Kauhanen, J.; Kurl, S. Hangover and the risk of stroke in middle-aged men. Acta Neurologica Scand. 2013, 127, 186–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kauhanen, J.; Kaplan, G.A.; Goldberg, D.D.; Cohen, R.D.; Lakka, T.A.; Salonen, J.T. Frequent hangovers and cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged men. Epidemiology 1997, 8, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piasecki, T.M.; Sher, K.J.; Slutske, W.S.; Jackson, K.M. Hangover frequency and risk for alcohol use disorders: Evidence from a longitudinal high-risk study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2005, 114, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piasecki, T.M.; Robertson, B.M.; Epler, A.J. Hangover and risk for alcohol use disorders: Existing evidence and potential mechanisms. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2010, 3, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohsenow, D.J.; Howland, J.; Winter, M.; Bliss, C.A.; Littlefield, C.A.; Heeren, T.C.; Calise, T.V. Hangover sensitivity after controlled alcohol administration as predictor of post-college drinking. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2012, 121, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckit, M.A.; Smith, T.L.; Tipp, J.E. The Self-Rating of the Effects of alcohol (SRE) form as a retrospective measure of the risk for alcoholism. Addiction 1997, 92, 979–988. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit, M.A.; Smith, T.L.; Danko, G.P.; Isacescu, V. Level of response to alcohol measured on the self-rating of the effects of alcohol questionnaire in a group of 40-year-old women. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2003, 29, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckit, M.A.; Smith, T.L. Changes over time in the self-reported level of response to alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004, 39, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schuckit, M.A.; Smith, T.L.; Danko, G.P.; Pierson, J.; Hesselbrock, V.; Bucholz, K.K.; Kramer, J.; Kuperman, S.; Dietiker, C.; Brandon, R.; et al. The ability of the Self-Rating of the Effects of Alcohol (SRE) Scale to predict alcohol-related outcomes five years later. J. Studies Alcohol Drugs 2007, 68, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckit, M.A.; Smith, T.L.; Clarke, D.F. Cross-sectional and prospective associations of drinking characteristics with scores from the Self-Report of the Effects of Alcohol questionnaire and findings from alcohol challenges. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 2282–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Išerić, E.; Scholey, A.; Verster, J.C. Alcohol hangovers as a predictor of the development of immune-related chronic diseases. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 48, 1995–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köchling, J.; Geis, B.; Wirth, S.; Hensel, K.O. Grape or grain but never the twain? A randomized controlled multiarm matched-triplet crossover trial of beer and wine. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verster, J.C.; Slot, K.A.; Arnoldy, L.; van Lawick van Pabst, A.E.; van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Benson, S.; Scholey, A. The Association between alcohol hangover frequency and severity: Evidence for reverse tolerance? J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, R.; McKinney, A.; Bus, L.D.; Olivier, B.; Slot, K.; Verster, J.C. Measurement of alcohol hangover severity: Development of the Alcohol Hangover Severity Scale (AHSS). Psychopharmacology 2013, 225, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slutske, W.S.; Piasecki, T.M.; Hunt-Carter, E.E. Development and initial validation of the Hangover Symptoms Scale: Prevalence and correlates of hangover symptoms in college students. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 27, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow, D.J.; Howland, J.; Minsky, S.J.; Greece, J.; Almeida, A.; Roehrs, T.A. The Acute Hangover Scale: A new measure of immediate hangover symptoms. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Verster, J.C.; Arnoldy, L.; van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Benson, S.; Scholey, A.; Stock, A.-K. The impact of mood and subjective intoxication on hangover severity. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuit, S.; Brookhuis, K.A.; Hayley, A.C.; Downey, L.A.; van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Verster, J.C. Self-reported physical, affective and somatic effects of ecstasy (MDMA): An observational study of recreational users. Curr. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 6, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Verster, J.C.; van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Benson, S.; Scholey, A.; Stock, A.-K. The assessment of overall hangover severity. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensel, K.O.; Longmire, M.R.; Köchling, J. Should population-based research steer individual health decisions? Aging 2019, 11, 9231–9233. [Google Scholar]

- Fernstrand, A.M.; Bury, D.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. Dietary intake of fibers: Differential effects in men and women on general health and perceived immune functioning. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1297053. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen, P.A.; Merlo, A.; Garssen, J.; Bijlsma, E.Y.; Engels, F.; Bruce, G.; Verster, J.C. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on academic functioning and mood: Data from Dutch pharmacy students, PhD candidates and post-docs. Data 2021, 6, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oostrom, E.C.; Mulder, K.E.W.; Verheul, M.C.E.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Thijssen, S.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Vlieg-Boerstra, B.; Garssen, J.; Verster, J.C. A healthier diet is associated with greater immune fitness. PharmaNutrition 2022, 21, 100306. [Google Scholar]

- Koyun, A.H.; Hendriksen, P.A.; Kiani, P.; Merlo, A.; Balikji, J.; Stock, A.-K.; Verster, J.C. COVID-19 lockdown effects on mood, alcohol consumption, academic functioning, and perceived immune fitness: Data from young adults in Germany. Data 2022, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verster, J.C.; Išerić, E.; Ulijn, G.A.; Oskam, S.M.P.; Garssen, J. Single-item assessment of Quality of Life: Scale validation and associations with mood and health outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5217. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, H.T. Nonparametric partial correlation and causal analysis. Soc. Methods Res. 1974, 2, 376–392. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, P. How Do I Produce Nonparametric Spearman partial Correlations Using SPSS? Available online: https://imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/partsp (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Turner, B.R.H.; Jenkinson, P.I.; Huttman, M.; Mullish, B.H. Inflammation, oxidative stress and gut microbiome perturbation: A narrative review of mechanisms and treatment of the alcohol hangover. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 48, 1451–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, L.P.; Varlinskaya, E. Adolescence. Alcohol sensitivity, tolerance, and intake. Recent Develop. Alcohol 2005, 17, 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstrup, J.S.; Stephens, R.; Grønbaek, M. Does the severity of hangovers decline with age? Survey of the incidence of hangover in different age groups. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2014, 38, 466–470. [Google Scholar]

- Verster, J.C.; Severeijns, N.R.; Sips, A.S.M.; Saeed, H.M.; Benson, S.; Scholey, A.; Bruce, G. Alcohol hangover across the lifespan: Impact of sex and age. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021, 56, 589–598. [Google Scholar]

- Bongers, I.M.B.; Van de Goor, L.A.M.; Van Oers, J.A.M.; Garretsen, H.F.L. Gender differences in alcohol-related problems: Controlling for drinking behaviour. Addiction 1998, 93, 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki, T.M.; Slutske, W.S.; Wood, P.K.; Hunt-Carter, E.E. Frequency and correlates of diary-measured hangoverlike experiences in a college sample. Psychol. Addictive Behav. 2010, 24, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohsenow, D.J.; Howland, J.; Arnedt, J.T.; Almeida, A.B.; Greece, J.; Minsky, S.; Kempler, C.S.; Sales, S. Intoxication with bourbon versus vodka: Effects on hangover, sleep, and next-day neurocognitive performance in young adults. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verster, J.C.; Vermeulen, S.A.; van de Loo, A.J.A.E.; Balikji, S.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Garssen, J.; Scholey, A. Dietary nutrient intake, alcohol metabolism, and hangover severity. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neighbors, C.; Leigh Leasure, J.; Shank, F.; Ryan, P.; Najjar, L.Z.; Sze, C.; Henderson, C.E.; Young, C.M. Physical activity as a moderator of the association between alcohol consumption and hangovers. Addict. Behav. 2024, 159, 108145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.M.; Rohsenow, D.J.; Piasecki, T.M.; Howland, J.; Richardson, A.E. Role of tobacco smoking in hangover symptoms among university students. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2013, 74, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohsenow, D.J.; Howland, J. The role of beverage congeners in hangover and other residual effects of alcohol intoxication: A review. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2010, 3, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetherill, R.R.; Fromme, K. Subjective responses to alcohol prime event-specific alcohol consumption and predict blackouts and hangover. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2009, 70, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stangl, B.L.; Vogt, E.L.; Blau, L.E.; Ester, C.D.; Gogineni, A.; Diazgranados, N.; Vatsalya, V.; Ramchandani, V.A. Pharmacodynamic determinants of hangover: An intravenous alcohol self-administration study in non-dependent drinkers. Addict. Behav. 2022, 135, 107428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T.L.; Horn, S.M.; Johnson, M.L.; Smith, T.L.; Carr, L.G. Hangover symptoms in Asian Americans with variations in the aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) gene. J. Stud. Alcohol 2000, 61, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Cleland, C.M.; Scheidell, J.D.; Berger, A.T. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in patterns of adolescent alcohol use and associations with adolescent and adult illicit drug use. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2014, 40, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutske, W.S.; Piasecki, T.M.; Nathanson, L.; Statham, D.J.; Martin, N.G. Genetic influences on alcohol-related hangover. Addiction 2014, 109, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, M.; Yokoyama, A.; Yokoyama, T.; Funazu, K.; Hamana, G.; Kondo, S.; Yamashita, T.; Nakamura, H. Hangover susceptibility in relation to aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotype, alcohol flushing, and mean corpuscular volume in Japanese workers. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2005, 29, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newlin, D.B.; Pretorius, M.B. Sons of alcoholics report greater hangover symptoms than sons of nonalcoholics: A pilot study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1990, 14, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCaul, M.E.; Turkkan, J.S.; Svikis, D.S.; Bigelow, G.E. Alcohol and secobarbital effects as a function of familial alcoholism: Extended intoxication and increased withdrawal effects. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1991, 15, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Span, S.A.; Earleywine, M. Familial risk for alcoholism and hangover symptoms. Addict. Behav. 1999, 24, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, R.; Holloway, K.; Grange, J.A.; Owen, L.; Jones, K.; Kruisselbrink, D. Does familial risk for alcohol use disorder predict alcohol hangover? Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 1795–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).