Feasibility, Acceptability, and Impact of Recovery-Oriented Practices in an Italian Community Mental Health Service: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Longitudinal Study

2.2.1. The MHRS

- Stuck (phases 1–2): feeling unable to cope or unwilling to seek help.

- Accepting help (phases 3–4): acknowledging the problem and seeking support.

- Believing (phases 5–6): gaining confidence in change and taking action.

- Learning (phases 7–8): experimenting with new approaches.

- Self-reliance (phases 9–10): managing goals independently.

2.2.2. Participants

2.2.3. Assessments

- Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) [64]: Assesses psychopathology and social functioning across 12 items covering behavioral, daily living, mental health, and socio-occupational difficulties. Scores range from 0 (no problem) to 4 (very severe), with higher totals reflecting greater severity.

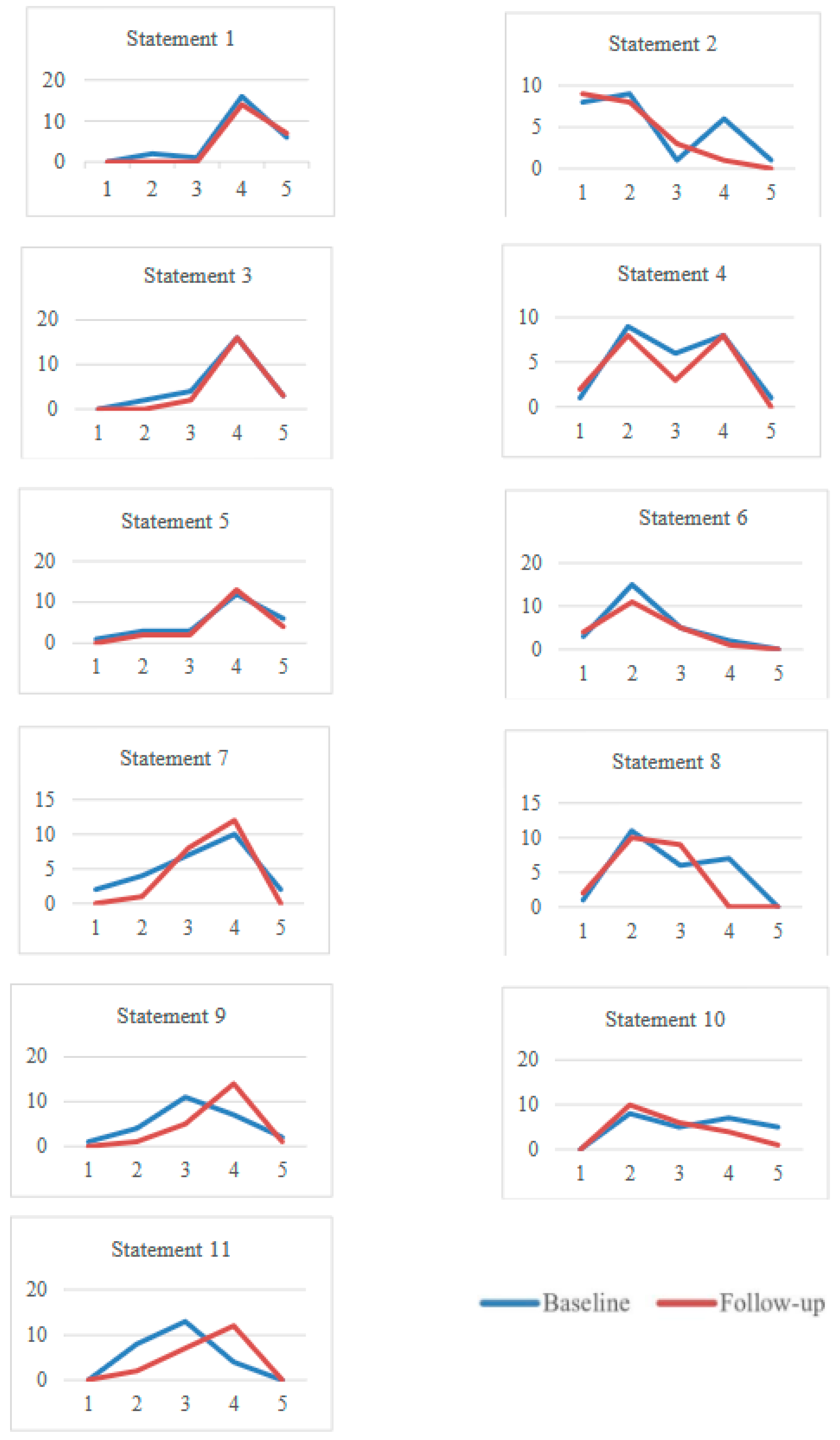

- An acceptability and feasibility assessment: Conducted at the study’s conclusion to assess the usability of MHRS in clinical practice. Participants rated the difficulty of using MHRS and its effectiveness in a recovery-oriented approach on a 5-point Likert scale. Staff completed 18 statements, while service users answered 10 (Table 1).

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Recovery-Oriented Focus Groups at the South Verona CMHS

- First focus group (June–September 2017, six meetings, avg. 12 participants): Focused on recovery education and MHRS training for recent trainees at South Verona CMHS.

- Second focus group (January–May 2018, eight meetings, avg. 17 participants): Explored strategies for implementing the recovery paradigm and forming a collaborative group within Verona DMH.

3. Results

3.1. Service Users’ Socio-Demographic and Clinical Characteristics from BL to FU

3.2. Recovery Star, Functioning, Psychopathology, Functional Autonomy, and Needs of Care from BL to FU

3.3. Assessing the Impact and Feasibility of Implementing MHRS a Recovery-Oriented Approach

3.4. Focus Groups

3.5. Advancements in Recovery-Oriented Practices at South Verona CMHS Post-Pilot Study

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- WHO. European Ministerial Conference on Mental Health. In Mental Health Declaration for Europe “Facing the Challenges, Building Solution”; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper: Improving the Mental Health of the Population: Towards a Strategy on Mental Health for the European Union; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- United Nations. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

- Caldas de Almeida, J.; Killaspy, H. Long-Term Mental Health Care for People with Severe Mental Disorders; Report for the European Commission: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Rehabilitation for Adults with Complex Psychosis; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A.; Ruggeri, M. The impact on psychiatric rehabilitation of personal recovery-oriented approach. J. Psychipathology 2020, 26, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, H.; Kalidindi, S.; Killaspy, H.; Glenn, R. Enabling Recovery: The Principles and Practice of Rehabilitation Psychiatry, 2nd ed.; Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Short Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS–S). In Multiaxial Presentation of the ICD-10 for Use in Adult Psychiatry; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Amering, M.; Farkas, M.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Panther, G.; Perkins, R.; Shepherd, G.; Tse, S.; Whitley, R. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maone, A.; D’Avanzo, B. Recovery. In Nuovi Paradigmi per la Salute Mentale, Psichiatri; Raffaello Cortina Editore: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, R.; Whittington, R.; Cramond, L.; Perkins, E. Contested understandings of recovery in mental health. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SLAM/SWLSTG. Recovery is for All: Hope, Agency and Opportunity in Psychiatry. In A Position Statement by Consultant Psychiatrists; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carozza, P. Principi di Riabilitazione Psichiatrica: Per un Sistema di Servizi Orientato Slla Guarigione, 9th ed.; Franco Angeli: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, T.R.E.; Pant, A. Long-term course and outcome of schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2005, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, R.P. Recovery from Disability: Manual of Psychiatric Rehabilitation; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bee, P.; Owen, P.; Baker, J.; Lovell, K. Systematic synthesis of barriers and facilitators to service user-led care planning. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, C.; Mary, Q.; Carr, S. Emerging Evidence Base for Adult Social Care Transformation; Social Care Institute for Excellence: Egham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health: Mental Health Division. New Horizons: Towards a Shared Vision for Mental Health; Department of Health: Mental Health Division: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson, P.; Holloway, F.; Killaspy, H. Enabling recovery for people with complex mental health needs. In A Template for Rehabilitation Services; Royal College of Psychiatrists, Faculty of Rehabilitation and Social Psychiatry: Wales, Scotland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Os, J.; Guloksuz, S.; Vijn, T.W.; Hafkenscheid, A.; Delespaul, P. The evidence-based group-level symptom-reduction model as the organizing principle for mental health care: Time for change? World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Community Engagement: Improving Health and Wellbeing and Reducing Health Inequalities; NICE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Shared decision making. In NICE Guidelines; NICE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO—Regional Office for Europe. The European Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 19.

- Giusti, L.; Ussorio, D.; Salza, A.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R. Easier Said Than Done: The Challenge to Teach “Personal Recovery” to Mental Health Professionals Through a Short, Targeted and Structured Training Programme. Community Ment. Health J. 2022, 58, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, L.; Boggian, I.; Carozza, P.; Lamonaca, D.; Svettini, A. Recovery in Italy: An Update. Int. J. Ment. Health 2016, 45, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Leamy, M.; Bacon, F.; Janosik, M.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Bird, V. International differences in understanding recovery: Systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2012, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A.; Ruggeri, M. An overview of mental health recovery-oriented practices: Potentiality, challenges, prejudices, and misunderstandings. J. Psychopathol. 2020, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, A.; Taylor, A.; Toney, R.; Meddings, S.; Whale, T.; Jennings, H.; Pollock, K.; Bates, P.; Henderson, C.; Waring, J.; et al. The impact of Recovery Colleges on mental health staff, services and society. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 28, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, C.; Rennick-egglestone, S.; Armstrong, V.; Borg, M.; Charles, A.; Duke, L.H.; Llewellyn-Beardsley, J.; Ng, F.; Pollock, K.; Pomberth, S.; et al. The Influence of Curator Goals on Collections of Lived Experience Narratives: A Qualitative Study. J. Recovery Ment. Health 2021, 4, 2371–2376. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, L.; Ussorio, D.; Salza, A.; Malavolta, M.; Aggio, A.; Bianchini, V.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R. Italian Investigation on Mental Health Workers’ Attitudes Regarding Personal Recovery From Mental Illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera San Juan, N.; Gronholm, P.C.; Heslin, M.; Lawrence, V.; Bain, M.; Okuma, A.; Evans-Lacko, S. Recovery From Severe Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review of Service User and Informal Caregiver Perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 712026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, F. Recovery e coproduzione. In Un Progetto Presso i Servizi di Salute Mentale della Provincia di Brescia; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi, F.; Chiaf, E.; Placentino, A.; Scarsato, G. Programma FOR: A Recovery College in Italy. J. Recovery Ment. Health 2018, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, A.; D’Avanzo, B.; D’Anza, V.; Montorfano, E.; Savio, M.; Corbascio, C.G. Involvement of users and relatives in mental health service evaluation. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontecedro, E.; Furlan, M.; Tossut, D.; Pascolo-Fabrici, E.; Balestrieri, M.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; D’Avanzo, B.; Castelpietra, G. Individual health budgets in mental health: Results of its implementation in the friuli venezia giulia region, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzina, R.; Marin, I. Work and recovery: From policies to individuals. Cad. Bras. Saúde Ment. 2021, 13, 64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Bonetto, C.; Bonora, F.; Cristofalo, D.; Killaspy, H.; Ruggeri, M. Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: A pilot study of an Italian social enterprise with a special ingredient. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 296. [Google Scholar]

- Pelizza, L.; Lorena, M.; Elisabetta, F.; Artoni, S.; Franzini, M.C.; Montanaro, S.; Andreoli, M.V.; Marangoni, S.; Ciampà, E.; Erlicher, D.; et al. Implementation of Individual Placement and Support in Italy: The Reggio Emilia Experience. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 1128–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placentino, A.; Lucchi, F.; Scarsato, G.; Fazzari, G. La Mental Health Recovery Star: Caratteristiche e studio di validazione della versione italiana. Il Pensiero Sci. Ed. 2018, 11, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Morosini, P.; Magliano, L.; Brambilla, L. VADO, Valutazione di Abilità, Definizione di Obiettivi: Manuale per la Riabilitazione in Psichiatria; Erickson, Collana di psicologia, Gardolo: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gigantesco, A.; Vittorielli, M.; Pioli, R.; Falloon, I.R.; Rossi, G.; Morosini, P. The VADO approach in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatr Serv. 2006, 57, 1778–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.; Salzer, M.; Ralph, R.; Sangster, Y.; Keck, L. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophr. Bull. 2004, 30, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggian, I.; Lamonaca, D.; Ghisi, M.; Bottesi, G.; Svettini, A.; Basso, L.; Bernardelli, K.; Merlin, S.; Liberman, R.P.; S.I.R. 2 group. “The Italian Study on Recovery 2” Phase 1: Psychometric Properties of the Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS), Italian Validation of the Recovery Assessment Scale. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A.; Iozzino, L.; Pozzan, T.; Cristofalo, D.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M. Performance and effectiveness of step progressive care pathways within mental health supported accommodation services in Italy. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A.; D’Addazio, M.; Zamparini, M.; Thornicroft, G.; Torino, G.; Zarbo, C.; Rocchetti, M.; Starace, F.; Casiraghi, L.; Ruggeri, M.; et al. Needs for care of residents with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and association with daily activities and mood monitored with experience sampling method: The DIAPASON study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2023, 32, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, G.; Boardman, J.; Slade, M. Making Recovery a Reality; Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tansella, M.; Amaddeo, F.; Burti, L.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Evaluating a community-based mental health service focusing on severe mental illness. The Verona experience. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 2006, 113, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senate of the Republic, 17th Legislature. Bill. Provisions on mental health protection aimed at implementing and developing the principles of Law No. 180 of May 13, 1978. Italy. 2017.

- WHO. Mental Health ATLAS 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Keen, E.L. The Outcome Star: A Tool for Recovery Orientated Services. Exploring the Use of the Outcome Star in a Recovery Orientated Mental Health Service; Edith Cowan University: Joondalup, WA, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- MacKeith, J.; Burns, S. User Guide; Mental Health Recovery Star: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchi, F.; Scarsato, G.; Placentino, A. Mental Health Recovery Star: User Guide (Italian Version); Il Chiaro del Bosco: Brescia, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Onifade, Y. The mental health recovery star. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2011, 15, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Bonetto, C.; Pozzan, T.; Procura, E.; Cristofalo, D.; Ruggeri, M.; Killaspy, H. Exploring gender impact on collaborative care planning: Insights from a community mental health service study in Italy. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy; DowJones-Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, C.; Williams, P.L.; Machingura, T.; Tse, S. A focus on recovery: Using the Mental Health Recovery Star as an outcome measure. Adv. Ment. Health 2016, 14, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dickens, G.; Weleminsky, J.; Onifade, Y.; Surgarman, P. Recovery Star: Validating user recovery. Psychiatrist 2012, 36, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, N. Report of Recovery Star Research Seminar; Institute of Mental Health and Triangle: Nottingham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tickle, A.; Walker, N.; Chueng, C. Professionals’ perceptions of the Mental Health Recovery Star. Mental Health Rev. J. 2013, 18, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Killaspy, H.; White, S.; Taylor, T.L.; King, M. Psychometric properties of the mental health recovery star. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amaddeo, F. Using large current databases to analyze mental health services. Epidemiol. Prev. 2018, 42, 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Erlicher, A.; Tansella, M. Health of the Nation Outcome Scales HoNOS: Una Scala per la Valutazione Della Gravità e dell’esito nei Servizi di Salute Mentale; II Pensiero Scientifico Editore: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Pozzan, T.; Corso, E.D.; Procura, E.; D’Astore, C.; Cristofalo, D.; Ruggeri, M.; Bonetto, C. Proprietà psicometriche della Scheda di Monitoraggio del Percorso Riabilitativo (MPR). Riv. Psichiatr. 2022, 57, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A.; Dal Corso, E.; Pozzan, T. Monitoring of the pathway of rehabilitation (MPR). J. Psychopathol. 2024, 30, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Loftus, L.; Thornicroft, G. The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN); RC of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Nicolaou, S.; Tansella, M. Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) (Italian Version); Dipartimento di Medicina e Sanità Pubblica, Sezione di Psichiatria, Università di Verona, Ospedale Policlinico: Verona, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Providers Forum. Southside Partnership—Recovery Star Implementation Report. 2009.

- Merriem Webster. Definition of Focus Group. 2018. Available online: www.merriam-webster.com (accessed on 5 June 2016).

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. A conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Rob, W.; Geoff, S.; Slade, M. Recovery colleges as a mental health innovation. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schattner, A.; Bronstein, A.; Jellin, N. Information and shared decision-making are top patients’ priorities. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.R.; Drake, R.E.; Wolford, G.L. Shared decision-making preferences of people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 1219–1221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A. Addressing challenges in functional and clinical recovery outcomes: The critical role of personal recovery. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 339, 116029. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.; Amore, M.; Galderisi, S.; Rocca, P.; Bertolino, A.; Aguglia, E.; Amodeo, G.; Bellomo, A.; Bucci, P.; Buzzanca, A.; et al. The complex relationship between self-reported ‘ personal recovery ’ and clinical recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 192, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessing, L.V.; Tønning, M.L.; Busk, J.; Rohani, D.; Frost, M.; Bardram, J.M.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M. Mood instability in patients with unipolar depression measured using smartphones and the association with measures of wellbeing, recovery and functioning. Nord J. Psychiatry 2024, 78, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Munro, I.; Taylor, B.J.; Griffiths, D. Mental health recovery: A review of the peer-reviewed published literature. Collegian 2017, 24, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, S.G.; Rosenheck, R.A. Integrating Peer-Provided Services: A Quasi-experimental Study of Recovery Orientation, Confidence, and Empowerment. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sells, D.L.; Davidson, L.; Jewell, C.; Falzer, P.; Rowe, M. The treatment relationship in peer-based and regular case management for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006, 57, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, D.S.; Anthony, W.A.; Ashcraft, L.; Johnson, E.; Dunn, E.C.; Lyass, A.; Rogers, E.S. The personal and vocational impact of training and employing people with psychiatric disabilities as providers. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2006, 29, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. Rapporto Salute Mentale Analisi dei Dati del Sistema Informativo per la Salute Mentale (SISM) Anno; Ministero della Salute: Rome, Italy, 2023.

| Domain | Professionals (N = 22) | Service Users (N = 21) |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty of MHRS Implementation | ||

| Negotiating different visions between user and professional | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.7) |

| Ensuring equal participation in MHRS | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) |

| Assigning responsibility in care planning | 3.2 (0.9) | 3.3 (0.8) |

| Adhering to intervention plan schedule | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.0 (0.9) |

| Completing MHRS within two weeks | 2.9 (1.1) | — |

| Achieved Results | ||

| Strengthening user involvement in decision-making | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.5) |

| Identifying new solutions for user needs | 4.1 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.5) |

| Uncovering previously hidden resources | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.6) |

| Improving user-professional trust | 3.9 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.7) |

| Increasing user engagement in their care plan | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.7) |

| BL (N = 25) Mean (SD) | FU (N = 25) Mean (SD) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 15 (60.0%) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.0 (9.9) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 19 (76.0%) | 16 (64.0%) | <0.001 |

| Married or in partnership | 6 (24.0%) | 9 (36.0%) | |

| Education | |||

| Low education | 13 (52%) | 13 (52%) | - |

| High education | 12 (48%) | 12 (48%) | |

| Work | |||

| Employed (Work, Student, Stage, …) | 9 (36.0%) | 14 (56.0%) | <0.001 |

| Unemployed (Housewife, Retired, …) | 16 (64.0%) | 11 (44.0%) | |

| Housing | |||

| Private accommodation | 14 (56.0%) | 14 (56.0%) | - |

| Supported housing | 11 (44.0%) | 11 (44.0%) | |

| Primary clinical diagnosis (DSM 5) | |||

| Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder | 17 (68.0%) | ||

| Other diagnosis (Mood disorders, Personality disorders, …) | 8 (32.0%) | ||

| Contact with CMHS (years) mean (CI) | 16 (12.5–19.5) | ||

| Acute ward admission in the previous 6 months | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.059 |

| Number of psychiatric drugs’ intake | 2.9 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.8) | 0.746 |

| Concurrent physical comorbidity | 8 (32.0%) | 8 (32.0%) | - |

| Current addiction (tobacco, alcohol, cannabinoid, ludopathy) | 0.8 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| BL (N = 25) Mean (SD) | FU (N = 24) Mean (SD) | p-Value * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHRS, Mean (SD) | 6.1 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.4) | 0.003 |

| (N = 24 couples) | (N = 23 couples) | ||

| 1. Managing mental health | 5.8 (1.8) | 6.6 (1.7) | 0.004 |

| 2. Physical health and self-care | 6.7 (2.3) | 7.25 (2.1) | 0.062 |

| 3. Living skills | 6.0 (2.0) | 6.5 (1.8) | 0.012 |

| 4. Social networks | 5.5 (2.2) | 5.8 (2.2) | 0.142 |

| 5. Work | 5.5 (2.4) | 6.0 (2.4) | 0.007 |

| (N = 24 couples) | (N = 23 couples) | ||

| 6. Relationships | 5.5 (2.6) | 6.2 (2.6) | 0.018 |

| 7. Addictive behavior | 7.0 (3.4) | 7.0 (3.1) | 0.914 |

| 8. Responsibilities | 8.1 (2.3) | 8.4 (1.97) | 0.05 |

| 9. Identity and self-esteem | 6.0 (1.8) | 6.5 (1.8) | 0.016 |

| 10. Trust and hope | 6.9 (1.9) | 6.6 (2.0) | 0.11 |

| FPS, Mean (SD) | 53 (19.7) | 62.2 (12.8) | 0.015 |

| HoNOS Mean (SD) | 12.6 (5.5) | 9.69 (4.6) | 0.001 |

| MPR, Mean (SD) | 8.7 (1.5) | 9.3 (1.5) | 0.003 |

| CAN Key-professionals | |||

| Total mean (SD) needs | 10.8 (4.5) | 9.6 (5.0) | 0.056 |

| Total (SD) met needs | 7.7 (3.7) | 7.6 (3.8) | 0.776 |

| Total (SD) unmet needs | 3.0 (0.5) | 2.0 (2.1) | 0.063 |

| Ratio met/unmet needs | 2.6 | 3.8 | |

| CAN Service users | |||

| Total mean (SD) needs | 9.8 (4.6) | 8.7 (4.6) | 0.78 |

| Total (SD) met needs | 7.2 (3.94) | 7.3 (4.16) | 0.94 |

| Total (SD) unmet needs | 2.6 (2.78) | 1.4 (1.74) | 0.026 |

| Ratio met/unmet needs | 2.8 | 5.2 |

| BL (N = 25) | FU (N = 20) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Managing mental health. | 5 (20%) | 5 (25%) |

| 2. Physical health and self-care. | 5 (20%) | 5 (25%) |

| 3. Living skills. | 4 (16%) | 5 (25%) |

| 4. Social networks. | 5 (20%) | 5 (25%) |

| 5. Work. | 12 (48%) | 9 (45%) |

| 6. Relationships. | 7 (28%) | 5 (25%) |

| 7. Addictive behavior. | 1 (4%) | 4 (20%) |

| 8. Responsibilities. | 2 (8%) | 2 (10%) |

| 9. Identity and self-esteem. | 2 (8%) | 3 (15%) |

| 10. Trust and hope. | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinelli, A.; Pozzan, T.; Procura, E.; D’Astore, C.; Cristofalo, D.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Impact of Recovery-Oriented Practices in an Italian Community Mental Health Service: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072280

Martinelli A, Pozzan T, Procura E, D’Astore C, Cristofalo D, Bonetto C, Ruggeri M. Feasibility, Acceptability, and Impact of Recovery-Oriented Practices in an Italian Community Mental Health Service: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(7):2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072280

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinelli, Alessandra, Tecla Pozzan, Elena Procura, Camilla D’Astore, Doriana Cristofalo, Chiara Bonetto, and Mirella Ruggeri. 2025. "Feasibility, Acceptability, and Impact of Recovery-Oriented Practices in an Italian Community Mental Health Service: A Pilot Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 7: 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072280

APA StyleMartinelli, A., Pozzan, T., Procura, E., D’Astore, C., Cristofalo, D., Bonetto, C., & Ruggeri, M. (2025). Feasibility, Acceptability, and Impact of Recovery-Oriented Practices in an Italian Community Mental Health Service: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 2280. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072280