Abstract

Background/Objectives: Previous reviews demonstrated stronger benefits of early interventions on cognition compared to motor outcome in preterm-born infants. Potentially, motor development needs more targeted interventions, including at least an active motor component. However, there is no overview focusing on such interventions in preterm-born infants, despite the increased risk for neuromotor delays. Methods: PubMed, Embase and Web of Science were systematically searched for (quasi-)randomized controlled trials regarding early interventions in preterm-born infants, with varying risks for neuromotor delay, and trials comprising an active motor component started within the first year were included. Study data and participant characteristics were extracted. The risk of bias was assessed with the Risk of Bias 2 tool. Results: Twenty-five reports, including twenty-one unique (quasi-)RCTs, were included and categorized as either pure motor-based interventions (n = 6) or family-centered interventions (n = 19). Of the motor-based interventions, four improved motor outcomes immediately after the intervention, and one of these also did so at follow-up, compared to five and one for family-centered approaches, respectively. Only five family-centered studies assessed long-term effects beyond age five, finding no greater efficacy than standard care. Overall, large variations were present for intervention intensity, type and outcomes between the included studies. Conclusions: Although methodological heterogeneity compromised conclusions, limited effects on motor outcome, in particular long-term outcome, were identified. Including a stronger motor-focused component embedded within a family-centered approach could potentially increase the impact on motor outcome, which would be of particular interest for infants showing early signs of neuromotor delay.

1. Introduction

Every year, an estimated 15 million babies are born worldwide before 37 weeks of gestation [1], 4.7% of them are born in Europe [2]. Although technical advances in neonatal care have increased the survival rate of extremely preterm infants [3], their vulnerability to neurodevelopmental disabilities remains a point of concern. An increasing number of studies examine the efficacy of early interventions within the first year of life with the aim of enhancing development and minimizing adverse outcomes. The importance of starting interventions early stems from the hypothesis of a benefit from the increased neural plasticity present during the first year of life [4]. The increasing number of studies on this topic resulted in Cochrane reviews with the most recent update published in January 2024 [5]. Here, the authors concluded that early interventions probably (low-certainty evidence) have a positive effect on cognitive and motor development during infancy, while high-certainty evidence was found for a more sustained effect up until preschool age, but only on the cognitive domain. Most early interventions encompass general developmental stimulation through parent education, enhancing parent–infant relationships and environmental enrichment. Potentially, motor development needs more targeted interventions, including at least an active motor component. Moreover, since thirty-six percent of very preterm-born infants present with motor difficulties at preschool age [6], a more delineated study of the efficacy of early interventions, including such an active motor component, on motor outcome is warranted. Such types of interventions could be of particular interest for infants showing early signs of neuromotor delay such as cerebral palsy (CP). CP is defined as a predominant sensorimotor disorder due to non-progressive lesions in the developing brain [7]. It is one of the most impairing outcomes after preterm birth, with a risk that increases exponentially with decreasing gestational age [6]. Another recent systematic review summarized interventions in infants and toddlers at high risk for or with a diagnosis of CP [8]. The authors reported very low-quality evidence for the effectiveness of task-specific motor training and constraint-induced movement therapy to improve motor function. However, this review included studies that provided therapy to participants up to the age of 32 months, which prevented the authors from drawing conclusions on the effect of early interventions within the first year of life. Moreover, although studied samples of infants at high risk for CP often encompass preterm-born infants, current reviews did not include both preterm and high-risk infants within their search strategy. Hence, the aim of this literature review is to provide an overview of studies in preterm-born infants with varying risks for neuromotor delay, reporting on the efficacy of early interventions, including an active motor component and starting within the first year of life.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper is written following the PRISMA statements for writing a systematic review [9] (see checklist in Supplementary Materials S3). No pre-registration was performed for this study.

2.1. Research Question

What is the recent evidence for early intervention within the first year of life including an active motor component (I) for preterm-born infants with or without a high risk for CP (P) on motor outcome (O)?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria, Information Sources, Search Strategy

PubMed, Embase and Web of Science were searched for papers published between August 2015 and February 2024. Backward citation tracking was performed for all included papers after inclusion based on full text. The search strategy was built upon (P) preterm infants with or without a high risk for CP, (I) early intervention and (O) motor or developmental outcome. A full search strategy can be found in Supplementary Materials S1. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

2.3. Selection Process

After the search was conducted, results were imported into Endnote to remove duplicates. Study selection was conducted independently by three reviewers (NDB, BS and BH) using Rayyan for screening of the title and abstract (round 1) and full text (round 2). Any disagreements were resolved through consensus via discussion. For interventions with unclear descriptions, clinical trial registrations or protocol papers were consulted whenever available.

2.4. Data Collection Process and Data Items

After full-text screening, tables of evidence were created by one reviewer (NDB) and checked by a second reviewer (LM). Thereby, studies were categorized into two groups based on their therapy content: 1) pure motor-based interventions and 2) general family-centered interventions. Studies were classified as pure motor-based in case their intervention focused predominantly on the improvement of motor development without incorporating components of a parent–infant relationship or parental education concerning other developmental domains. In contrast, in studies categorized as general family-centered interventions, parental education relating to the general development, behavior and parent–infant relationships played a key role. Any uncertainties were discussed with a second reviewer (CVDB or BH). See Supplementary Material S2 for an overview of theoretical frameworks and content of intervention programs.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The Cochrane risk of bias tool 2 was used to assess the risk of bias [10], conducted by one reviewer (NDB), with consultations from a second reviewer in ambiguous or unclear cases. The randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of reported results were assessed for potential bias. For the question “Were participants aware of their assigned intervention during the trial?”, it was assumed that infants were unaware of their assigned intervention due to their age. Regarding the question “Were carers and people delivering the interventions aware of participants’ assigned intervention during the trial?”, if parents/caregivers were involved in the intervention, it was interpreted as “yes” since they were aware of the intervention. Similarly, if healthcare professionals delivered the intervention directly to the child without parental involvement, it was interpreted from the perspective of the healthcare professional. Additionally, the question ‘allocation based on time of admission’ was rated as ‘random’ if allocation blocks were sufficiently long (several months) and age of inclusion was limited by gestational age, thereby preventing manipulation of allocation through delayed inclusion.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

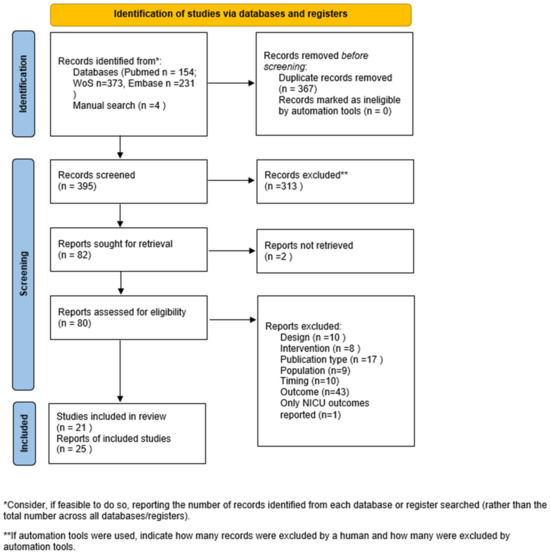

The search strategy resulted in 154 PubMed, 373 Web of Science and 231 EMBASE articles. After duplicates were removed, 395 articles were screened on title and abstract, resulting in 82 articles for full-text screening and 21 for final inclusion. After manual screening of reference tables, we added another 4 articles. In total, we included 25 articles in this review (see Figure 1 for flow chart) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. These 25 articles covered 21 unique studies.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study inclusion. NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, n: number.

3.2. Study and Participant Characteristics

All motor-based studies (n = 6) were unique and included a randomized, evaluator-blinded design [11,12,13,14,15,16]. The final sample sizes for which results were reported ranged from 16 to 44 infants. The family-centered interventions (n = 19, [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]) also mainly involved studies with a randomized, evaluator-blinded design. Only one study used a non-blinded quasi-RCT [23], and one study did not report on blinding of the assessors [20]. The final sample sizes for which results were reported ranged from 11 to 242. Two RCTs, one conducted in the Netherlands [21,25,32] and one in Australia [29,30,31], each covered three publications included in this systematic review.

Overall, most studies were conducted in Western countries like the USA [11,13,20,22], Australia [24,29,30,31] and European nations [12,17,21,25,26,28,32,33], and one study included Italian and Danish participants [16]. Studies were further conducted in Brazil [14,15,23], South Korea [34], Switzerland [35] and Turkey [18,19,27]. A more detailed overview of the study and participant characteristics is provided in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

Table 3.

Participant characteristics.

Risk of bias analysis using the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2 revealed only one study with low overall bias which was classified as a general family-centered intervention [35]. Except for two studies with high concerns [20,23], most other family-centered interventions were identified with some concerns. Of the motor-based interventions, two studies had some concerns [12,15], while four had high concerns [11,13,14,16]. Bias risks were primarily due to a lack of blinding during outcome measurement and the absence of predefined statistical plans for comparing final results.

3.3. Methodological Characteristics of the Interventions

3.3.1. Motor-Based Interventions

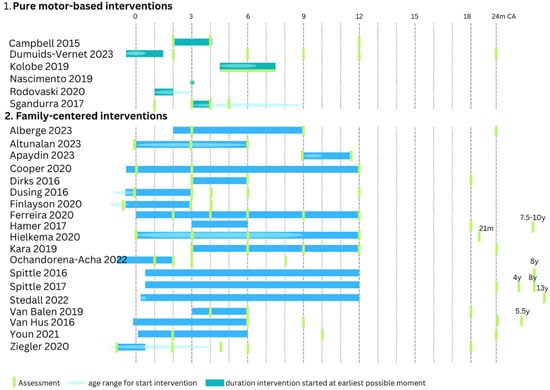

A detailed overview of the methodological characteristics of the intervention can be found in Table 2 and Figure 2. Each study within the motor-based interventions consisted of a different therapy content including tethered kicking [11], crawling training with a mini-skateboard [12] or robotic system [13], reaching with [15] or without [14] a visual component or general motor stimulation [16]. As a control intervention, two studies used standard of care [15,16], two studies did not intervene in their control group [11,14] and two other studies used a control intervention with the same intensity [12,13]. Therapy intensity in the experimental group varied from one 4 min training [14] to 30–45 min practice daily for four weeks [16]. All interventions were delivered at home either by a therapist [12,14] or by a caregiver with support from a therapist at home [11,15] or remotely [16]. In one study, the therapist provider was not described [13]. The intervention started in all studies within the first 6.5 months corrected age. To assess intervention efficacy on motor outcome, three motor-based interventions included at least a standardized assessment for motor development such as the Infant Motor Profile (IMP), Test of Infant Motor Performance (TIMP), Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) or the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (Bayley-III) [12,15,16]. The three other studies only reported intervention-specific assessments such as quantitative outcomes from the robotic crawling device and suit [13] or video recordings of tethered kicking [11] or reaching behavior [14]. In two studies, follow-up lasted until 12 months corrected age [11,12], while the other four studies only reported immediate post-intervention effects.

Figure 2.

Overview of (1) pure motor-based interventions and (2) family-centered interventions. For the age to start the intervention, a range of ages was often used; this is indicated with a light blue ellipse. When a study started at a fixed age, no ellipse was drawn. The duration of an intervention is indicated with a bar assuming the earliest possible moment of starting. When the intervention starts at an older age (within the age range for the start of the intervention), the entire bar shifts towards the new starting age [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. CA = corrected age, y = year, m = months.

3.3.2. Family-Centered Interventions

Within the general family-centered interventions, similar therapy concepts were often used across different studies, with COPCA [21,25,26,27,32,35], VIBeS Plus program (i.e., Victorian Infant Brain Studies) [29,30,31] and SPEEDI [22,24] being the most frequently used. As a control intervention, eleven studies used standard of care [17,22,23,24,28,29,30,31,33,34,35], and other studies used a control intervention with the same intensity [18,19,20,26,27] or traditional physiotherapy, the intensity of which varied depending on the pediatricians’ advice [21,25,32]. Regarding the experimental group, a large variation in therapy frequency and duration was found, with therapy intensity varying from 45–50 min per month over a six-month period [18] to 15–20 min per day during one year [20]. Most studies were delivered at home by the caregivers with support from a therapist. Three studies did not include home visits. In the study of Alberge et al., the therapy was delivered in a private practice by a psychomotor therapist [17], Ferreira et al. conducted their intervention program during standard follow-up assessments at the hospital [23], and Youn et al. provided group sessions by a pediatric physiotherapist in an outpatient center [34]. Four studies started the intervention already in the NICU before discharge [22,24,28,33]. Most other studies started the intervention within 3 to 4 months corrected age, except for three studies [17,19,26] that started at 9 to 10 months corrected age. To assess intervention efficacy on motor outcome, all studies that reported outcomes within the first two years of age included a motor developmental assessment using the IMP, TIMP, AIMS and/or Bayley-II or III. Studies beyond two years of age used the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales [25] or the Movement Assessment Battery for Children, second version (M-ABC-2) [29,30,31,33]. Follow-up lasted most frequently until 18 to 24 months corrected age. Only three studies focused solely on the immediate post-intervention effects [18,19,20], while five studies were focused on or included long-term outcomes beyond 2 years of age [25,29,30,31,33].

3.4. Intervention Effects

3.4.1. Motor-Based Interventions

All motor-based interventions reported on the immediate post-intervention effects. Only the studies of Dumuids-Vernet et al. and Campbell et al. comprised a longitudinal follow-up analysis including follow-up assessments until 12 months corrected age. Dumuids-Vernet et al. found significantly better outcomes on the fine and gross motor scales of the Bayley-III after Crawli training compared to regular training in prone or no training immediately post-intervention and in their longitudinal follow-up analysis [12]. Positive effects were also reported by Sgandurra et al. [16], showing that the CareToy system was significantly better than standard care for outcomes on IMP and AIMS immediately after intervention. Kolobe et al. further reported that both reinforcement learning and error-based learning during crawling training on the robotic device resulted in a greater increase in arm and trial-and-error efforts compared to reinforcement learning alone [13]. Nascimento et al. found that reaching training with sticky mittens resulted in improved reaching compared to no training [14]. In contrast, Campbell et al. did not find an effect of tethered kicking training immediately after the intervention, nor in their longitudinal follow-up analysis, compared to no intervention [11]. Also, Rodovanski et al. did not find an effect of adding parental education on early stimulation targeting visual and motor functions to standard care on TIMP outcomes compared to standard care alone [15].

3.4.2. Family-Centered Interventions

In the general family-centered interventions, mixed findings were found when compared to standard care. Van Hus et al. demonstrated longitudinal follow-up effects of the Infant Behavioral Assessment and Intervention Program on motor development (i.e., Bayley-II, M-ABC-2) across all time points [33]. Alberge et al. only found between-group differences in motor development (Bayley-III) at 9 m corrected age, but not at 24 m corrected age [17]. Two other studies were not able to demonstrate between-group differences immediately post-intervention or at follow-up [28,34], while Ferreira et al. found higher scores for gross motor development on Bayley-III immediately post-intervention in favor of the control group [23].

Three studies compared their early intervention program with a control group of equal intensity and did not reveal significant between-group differences for early motor development immediately post-intervention [18,19,20] or at follow-up [18]. Yet, Apaydin et al. additionally reported within-group improvements for motor development on Bayley-III only in the experimental group [19].

Significant differences in favor of COPCA compared to traditional infant physiotherapy were demonstrated by Dirks et al., with infants receiving COPCA being more often bathed in a sitting position at 6 m corrected age [21], and by Ziegler et al. showing better scores on the variation and performance domain of the IMP at 18 m corrected age [35]. Although no further between-group differences were found for postural control before 18 m corrected age [32], early motor development assessed with the IMP and Bayley II [26] or Bayley III [27,35] or motor outcome at primary school age (7.5 to 10 years, M-ABC-2) [25], within-group differences for both groups were present, suggesting improved postural control [32] and fine and gross motor development on Bayley-III [27] independent of group allocation.

Varying results were found for SPEEDI compared to standard care. Dusing et al. demonstrated within-group improvements, but no between-group differences in reaching skill or early motor development (TIMP, Bayley-III) [22]. In contrast, Finlayson et al. found significantly fewer infants with absent fidgety movements at 3 m corrected age and better gross motor scores on Bayley-III at 4 m corrected age in favor of SPEEDI compared to standard care [24].

From the VIBeS Plus program, only publications with long-term follow-up were included [29,30,31]. In this RCT, no evidence was found for an effect on motor outcome, as motor scores on the M-ABC-2 were similar between the intervention group and standard care group at 8-year [29] and 13-year [31] follow-up.

3.4.3. Covariates

Interestingly, early interventions seem to be more beneficial for infants born from mothers with a lower educational level or in families with higher social risks. The VIBeS plus program reported that 8- and 13-year-old children with higher social risk have better motor scores (M-ABC-2) after the intervention program compared to the standard care group, while this was not the case for children with lower social risk [30,31]. Also, Alberge et al. found a stronger effect of their psychomotor therapy on fine motor scores (Bayley-III) in infants from mothers with a lower educational level [17]. However, Van Hus et al. did not find a clear intervention effect of maternal education [33]. In contrast, these authors reported that infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia benefited more from the early intervention, compared to infants without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Finally, Cooper et al. showed that gestational age and small for gestational age were correlated with the TIMP change scores (from 0 to 3 months corrected age) during the first 3 months of their one-year intervention, indicating that a higher gestational age or birth weight was associated with a higher increase in TIMP scores [20]. (A detailed overview of the results for each study can be found in Supplementary Materials S3.)

4. Discussion

This systematic review provided an overview of the evidence on the effectiveness of early interventions with an active motor component started in the first year of life in preterm-born infants with varying risks for neuromotor delays. We included 25 studies, including 21 unique (quasi-)RCTs, which were categorized as either pure motor-based interventions (n = 6) or family-centered interventions (n = 19). Four pure motor-based interventions revealed improved motor outcomes immediately post-intervention, one of which also did so at follow-up, while for the family-centered interventions, this was the case for only five studies and one study, respectively. Subsequently, 2 motor-based interventions and 11 family-centered interventions did not identify motor improvements immediately after the intervention, compared to a control group of equal intensity of traditional physiotherapy or standard care. Moreover, long-term effects beyond the age of five years of such early intervention programs were studied only by five family-centered interventions and were not deemed more efficacious compared to standard care [25,29,30,31,33]. The lack of significant findings could potentially be explained by the fact that standard care and traditional physiotherapy are often already at a high level. Moreover, while the transfer to daily life activities may be more limited in the motor-based interventions [36] due to the lack of providing challenging environments for the infant in daily life or focusing on one specific motor skill (i.e., crawling, reaching or kicking) [11,12,13,14,15], motor development might still not be targeted specifically enough within the family-centered interventions. We could hypothesize that for improving motor development, a more direct approach is required, like in the motor-based interventions, rather than general motor stimulation embedded in a broader developmental stimulation program in the family-centered interventions. If so, this could be of particular interest for infants who are at high risk for CP or who show early signs of CP. Indeed, in their meta-analysis, Baker et al. concluded that task-specific motor training improves motor function in infants and toddlers with CP [8]. However, the conclusions of Baker and colleagues were based on low-quality evidence, urging the need for high-level RCTs.

Moreover, CP is a condition that does not solely affect motor outcome [7]. Also, preterm-born infants in general have an increased risk for developmental problems beyond the motor domain [6]. Hence, providing purely motor-based interventions would not serve these other developmental concerns, and we know that high-certainty evidence is already present for the positive impact of early interventions on cognitive outcome in infants born preterm. Consequently, it would be of interest to study CP-specific outcomes on the efficacy of targeted motor interventions embedded within a family-centered intervention and find a new balance between both. On the one hand, we know that based on the principle of motor learning and experience-dependent neuroplasticity [37], training should be specific. In this way, the motor component will boost the motor skills in a short time, when age matters and brain plasticity is still high, underlining the importance of a targeted motor component for improving motor outcomes. On the other hand, it is already well known that parents play an indisputable role within early interventions [5]. Parents will learn how to create stimulating trial-and-error experiences which will help the transfer of learned skills to activities of daily living. Parents will acquire the knowledge of implementing these principles, facilitating their sustained implementation well beyond the intervention time frame, thereby extending the impact.

Furthermore, new interventions should study if long-term effects would be enhanced by implementing boost programs. So far, long-term motor outcomes beyond the age of five years have not shown an effect [25,29,30,31,33]. However, these studies evaluated the effect of one intervention period. We hypothesize that the mechanisms of experienced-dependent neuroplasticity, which would assume restructuring of the brain in the first year of life, are also the basis of a long-term effect, indicating the need to maintain stimulation of the acquired neural pathways to keep them active and effective [37]. Another hypothesis could be that the neural groups responsible for early motor milestones and trained with the early interventions differentiate from the neural groups needed for more high-level motor skills which are often shown delayed at older ages [38].

Future research should also take into account that personal and environmental aspects could be determining factors influencing the (long-term) effects of early intervention, such as the social risk profile [30,31]. The inclusion of CP-related outcomes to evaluate therapies specifically for CP and better identification of infant and family characteristics that influence treatment outcomes would aid in delineating which kind of early intervention the infant will benefit from the most, and result in improving patient selection and cost-effectiveness and decreasing waiting times for starting specific early interventions.

However, this systematic review also has some limitations. At the study level, only a few studies included the interaction between group and time in their statistical analyses, which is needed to examine if there are differences between groups over time. Additionally, preterm birth contains still a rather large range of gestational ages with differences in expected outcomes, and more specific CP-related outcomes were often lacking even in the studies focusing on infants with a high risk for CP. Furthermore, specifically for the family-centered interventions, we were not able to extract the amount of stimulation parents had attributed to the motor development compared to other developmental domains from the articles. Hence, this needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results. At the review level, we need to acknowledge the date restriction, since we have searched for eligible articles from 2015 onwards. We aimed to focus on studies in the past decade due to the improved neonatal care, in particular for non-invasive respiratory support, coinciding with an increase in survival to discharge and decrease in morbidity [39]. Also, articles published after February 2024 were not included. A quick (not systematic) search already showed three new interesting papers within the scope of this review [40,41,42]. Nevertheless, this date restriction needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results. Moreover, we need to acknowledge that the inclusion criteria (at least 50% of the infants being preterm) led to the exclusion of some relevant studies such as BabyCIMT [43,44], and that the content of the intervention can only be interpreted based upon published information from the authors. It is possible that our interpretations of interventions may not reflect what has occurred due to a lack of detail in the papers. Also, the pre-registration of the protocol and performance of a meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis would have strengthened the conclusions of this review. However, methodological heterogeneity was very high, including a high amount of differences between intervention method, intensity and frequency, in outcome measures as well as the kind of scores (scaled score, composite score, raw scores) reported. Moreover, often it was not clear whether the improvements could be attributed to more than just spontaneous evolution or maturation of motor function. In particular, since all except one study [14] investigated the effect of an intervention over several weeks, spontaneous maturation of motor function resulting in better motor scores can be expected. Some studies have countered this by reporting the percentile scores calculated for specific age ranges.

Nevertheless, this review provided a detailed overview of the efficacy of early interventions including an active motor component in preterm-born infants with varying risks for neuromotor delays, further improving our knowledge of such early interventions on motor development and providing directions for future research.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review provided an overview of the evidence on the effectiveness of early interventions with an active motor component in preterm-born infants with varying risks for neuromotor delay, which were classified as either pure motor-based interventions or family-centered interventions. Although methodological heterogeneity between studies compromised study conclusions and clinical implications, we identified limited effects of these early interventions on motor outcome, in particular for long-term follow-up. Acknowledging the importance of family-centered interventions for other outcomes, we hypothesize that including a stronger motor-focused component within a family-centered approach would increase the impact on motor outcome, which would be of particular interest for infants at high risk for CP.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14041364/s1: Supplementary Materials S1: Search strategy; Supplementary Materials S2: Theoretical frameworks and description of therapies; Supplementary Materials S3: Overview of study results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D.B. and C.V.d.B.; methodology, N.D.B., C.V.d.B. and B.S.; formal analysis, N.D.B. and L.M.; investigation, N.D.B., B.H., L.M. and B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.D.B.; writing—review and editing, BH, L.M., C.V.d.B. and B.S.; visualization, N.D.B.; supervision, C.V.d.B. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIMS | Alberta Infant Motor Scale |

| BAYLEY-III | Bayley Scale of Infant Development, third version |

| COPCA | COPing and CAring for infants with special needs |

| CP | Cerebral palsy |

| IMP | Infant Motor Profile |

| M-ABC-2 | Movement Assessment Battery for Children, second version |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SPEEDI | Supporting Play Exploration and Early Developmental Intervention |

| TIMP | Test of Infant Motor Performance |

| VIBeS Plus | Victorian Infant Brain Studies |

References

- Althabe, F.; Howson, C.P.; Kinney, M.; Lawn, J. Born Too Soon: The global epidemiology of 15 milion preterm infants. Reprod Health 2013, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Vogel, J.P.; Moller, A.-B.; Lumbiganon, P.; Petzold, M.; Hogan, D.; Landoulsi, S.; Jampathong, N.; Kongwattanakul, K.; Laopaiboon, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saigal, S.; Doyle, L.W. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 2008, 371, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Early diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, J.; Doyle, L.W.; Tripathi, T.; Boyd, R.; Anderson, P.J.; Spittle, A. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 2024, CD005495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, A.; Govaert, P.; Oostra, A.; Naulaers, G.; Ortibus, E.; Broeck, C.V.D. Neurodevelopmental outcome in very preterm and very-low-birthweight infants born over the past decade: A meta-analytic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Niles, N.; Kysh, L.M.; Sargent, B. Effect of Motor Intervention for Infants and Toddlers with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2022, 34, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Savović, J.; Page, M.; Elbers, R.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing Risk of Bias in a Randomized Trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021); Higgins, J., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M., Welch, V., Eds.; Cochrane Training: London, UK, 2021; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Campbell, S.K.P.; Cole, W.; Boynewicz, K.P.; Zawacki, L.A.; Clark, A.; Gaebler-Spira, D.; Deregnier, R.-A.; Kuroda, M.M.; Kale, D.; Bulanda, M.P.; et al. Behavior During Tethered Kicking in Infants with Periventricular Brain Injury. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumuids-Vernet, M.-V.; Forma, V.; Provasi, J.; Anderson, D.I.; Hinnekens, E.; Soyez, E.; Strassel, M.; Guéret, L.; Hym, C.; Huet, V.; et al. Stimulating the motor development of very premature infants: Effects of early crawling training on a mini-skateboard. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1198016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolobe, T.H.A.; Fagg, A.H. Robot Reinforcement and Error-Based Movement Learning in Infants with and Without Cerebral Palsy. Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A.L.; Toledo, A.M.; Merey, L.F.; Tudella, E.; de Almeida Soares-Marangoni, D. Brief reaching training with ‘sticky mittens’ in preterm infants: Randomized controlled trial. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2019, 63, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodovanski, G.P.; Reus, B.A.B.; Damiani, A.V.C.; Mattos, K.F.; Moreira, R.S.; dos Santos, A.N. Home-based early stimulation program targeting visual and motor functions for preterm infants with delayed tracking: Feasibility of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 116, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgandurra, G.; Lorentzen, J.; Inguaggiato, E.; Bartalena, L.; Beani, E.; Cecchi, F.; Dario, P.; Giampietri, M.; Greisen, G.; Herskind, A.; et al. A randomized clinical trial in preterm infants on the effects of a home-based early intervention with the ‘CareToy System. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberge, C.; Ehlinger, V.; Noack, N.; Bolzoni, C.; Colombié, B.; Breinig, S.; Dicky, O.; Delobel, M.; Arnaud, C. Early psychomotor therapy in very preterm infants does not improve Bayley-III scales at 2 years. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunalan, T.; Sarı, Z.; Doğan, T.D.; Hacıfazlıoğlu, N.E.; Akman, I.; Altıntaş, T.; Uzer, S.; Akçakaya, N.H. Early developmental support for preterm infants based on exploratory behaviors: A parallel randomized controlled study. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydın, U.; Yıldız, R.; Yıldız, A.; Acar, Ş.S.; Gücüyener, K.; Elbasan, B. Short-term effects of SAFE early intervention approach in infants born preterm: A randomized controlled single-blinded study. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.M.; Girolami, G.L.; Kepes, B.; Stehli, A.; Lucas, C.T.; Haddad, F.; Zalidvar, F.; Dror, N.; Ahmad, I.; Soliman, A.; et al. Body composition and neuromotor development in the year after NICU discharge in premature infants. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 88, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, T.; Hielkema, T.; Hamer, E.G.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; Hadders-Algra, M. Infant positioning in daily life may mediate associations between physiotherapy and child development-video-analysis of an early intervention RCT. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53–54, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusing, S.C.; Tripathi, T.; Marcinowski, E.C.; Thacker, L.R.; Brown, L.F.; Hendricks-Muñoz, K.D. Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention versus usual care to enhance development outcomes during the transition from the neonatal intensive care unit to home: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Ferreira, R.; Alves, C.R.L.; de Castro Magalhães, L. Effects of family-focused early intervention on the neurodevelopment of children at biological and/or social risks: A quasi-experimental randomized controlled trial. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 192, 1164–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, F.; Olsen, J.; Dusing, S.C.; Guzzetta, A.; Eeles, A.; Spittle, A. Supporting Play, Exploration, and Early Development Intervention (SPEEDI) for preterm infants: A feasibility randomised controlled trial in an Australian context. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 151, 105172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, E.G.; Hielkema, T.; Bos, A.F.; Dirks, T.; Hooijsma, S.J.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; Toonen, R.F.; Hadders-Algra, M. Effect of early intervention on functional outcome at school age: Follow-up and process evaluation of a randomised controlled trial in infants at risk. Early Hum. Dev. 2017, 106–107, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielkema, T.; Hamer, E.G.; Boxum, A.G.; La Bastide-Van Gemert, S.; Dirks, T.; Reinders-Messelink, H.A.; Maathuis, C.G.B.; Verheijden, J.; Geertzen, G.H.B.; Hadders-Algra, M.; et al. LEARN2MOVE 0–2 years, a randomized early intervention trial for infants at very high risk of cerebral palsy: Neuromotor, cognitive, and behavioral outcome. Disabil Rehabil 2020, 42, 3752–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, O.K.; Sahin, S.; Yardimci, B.N.; Mutlu, A. The role of the family in early intervention of preterm infants with abnormal general movements. Neurosciences 2019, 24, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochandorena-Acha, M.; Terradas-Monllor, M.; Sala, L.L.; Sánchez, M.E.C.; Marti, M.F.; Pérez, I.M.; Agut-Quijano, T.; Iriondo, M.; Casas-Baroy, J.C. Early Physiotherapy Intervention Program for Preterm Infants and Parents: A Randomized, Single-Blind Clinical Trial. Children 2022, 9, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, A.J.; Barton, S.; Treyvaud, K.; Molloy, C.S.; Doyle, L.W.; Anderson, P.J. School-Age Outcomes of Early Intervention for Preterm Infants and Their Parents: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, A.J.; Treyvaud, K.; Lee, K.J.; Anderson, P.J.; Doyle, L.W. The role of social risk in an early preventative care programme for infants born very preterm: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedall, P.M.; Spencer-Smith, M.M.; Mainzer, R.M.; Treyvaud, K.; Burnett, A.C.; Doyle, L.W.; Spittle, A.J.; Anderson, P.J. Thirteen-Year Outcomes of a Randomized Clinical Trial of Early Preventive Care for Very Preterm Infants and Their Parents. J. Pediatr. 2022, 246, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Balen, L.C.; Dijkstra, L.-J.; Dirks, T.; Bos, A.F.; Hadders-Algra, M. Early Intervention and Postural Adjustments during Reaching in Infants at Risk of Cerebral Palsy. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 31, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hus, J.W.P.; Jeukens-Visser, M.; Koldewijn, K.; Holman, R.; Kok, J.H.; Nollet, F.; Van Wassenaer-Leemhuis, A.G. Early intervention leads to long-term developmental improvements in very preterm infants, especially infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, Y.-A.; Shin, S.-H.; Kim, E.-K.; Jin, H.-J.; Jung, Y.-H.; Heo, J.-S.; Jeon, J.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Sung, I.-K. Preventive intervention program on the outcomes of very preterm infants and caregivers: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, S.A.; von Rhein, M.; Meichtry, A.; Wirz, M.; Hielkema, T.; Hadders-Algra, M.; The Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-Up Group. The Coping with and Caring for Infants with Special Needs intervention was associated with improved motor development in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, M.A.; Harbourne, R.T.; Dusing, S.C.; McCoy, S.W. Grounding Early Intervention: Physical Therapy Cannot Just Be About Motor Skills Anymore. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleim, J.A.; Jones, T.A. Principles of Experience-Dependent Neural Plasticity: Implications for Rehabilitation After Brain Damage. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2008, 51, S225–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Variation and Variability: Key Words in Human Motor Development. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.L.Y.; E Olsen, J.; Huang, L.; Dalziel, K.M.; A Boland, R.; Burnett, A.C.; Haikerwal, A.; Spittle, A.J.; Opie, G.; E Stewart, A.; et al. Changing consumption of resources for respiratory support and short-term outcomes in four consecutive geographical cohorts of infants born extremely preterm over 25 years since the early 1990s. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton de Tournai, A.; Herman, E.; Ebner-Karestinos, D.; Gathy, E.; Araneda, R.; Renders, A.; De Clerck, C.; Kilcioglu, S.; Dricot, L.; Macq, B.; et al. Hand-Arm Bimanual Intensive Therapy Including Lower Extremities in Infants with Unilateral Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2445133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, B.R.; Bowen, J.; Morgan, C.; Novak, I.; Badawi, N.; Elliott, E.; Dwyer, G.; Venkatesha, V.; Harvey, L.A. The Best Start Trial: A randomised controlled trial of ultra-early parent-administered physiotherapy for infants at high risk of cerebral palsy or motor delay. Early Hum. Dev. 2024, 198, 106111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkarit, N.; Tapanya, W.; Panmatchaya, C.; Sangpasit, A.; Thatawong, K. Effects of 4 weeks of play in standing and walking on gross motor ability and segmental trunk control in preterm infants using a playpen: A randomized control trial. Early Hum. Dev. 2024, 198, 106111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, A.-C.; Nordstrand, L.; Ek, L.; Lennartsson, F.; Sjöstrand, L.; Tedroff, K.; Krumlinde-Sundholm, L. The effectiveness of Baby-CIMT in infants younger than 12 months with clinical signs of unilateral-cerebral palsy; an explorative study with randomized design. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 72, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamudot, R.; Parush, S.; Rigbi, A.; Horovitz, R.; Gross-Tsur, V. Effectiveness of Modified Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy Compared with Bimanual Therapy Home Programs for Infants With Hemiplegia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2018, 72, 7206205010p1–7206205010p9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).