Rasch Measurement Model Supports the Unidimensionality and Internal Structure of the Arabic Oswestry Disability Index

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Outcome Measures

Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Sample Size Estimation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 2023, 5, e316–e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborator. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Smeets, R.; Koke, A.; Lin, C.W.; Ferreira, M.; Demoulin, C. Measures of function in low back pain/disorders: Low Back Pain Rating Scale (LBPRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Progressive Isoinertial Lifting Evaluation (PILE), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ). Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. 11), S158–S173. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J.R.; Norvell, D.C.; Hermsmeyer, J.T.; Bransford, R.J.; DeVine, J.; McGirt, M.J.; Lee, M.J. Evaluating common outcomes for measuring treatment success for chronic low back pain. Spine 2011, 36, S54–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, R.C.; Welander, A.; Stowell, C.; Cha, T.D.; Chen, J.L.; Davies, M.; Fairbank, J.C.; Foley, K.T.; Gehrchen, M.; Hagg, O.; et al. A proposed set of metrics for standardized outcome reporting in the management of low back pain. Acta Orthop. 2015, 86, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, M.; Fairbank, J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine 2000, 25, 3115–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Couper, J.; Davies, J.B.; O’Brien, J.P. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 1980, 66, 271–273. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine 2000, 25, 2940–2952, discussion 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algarni, A.S.; Ghorbel, S.; Jones, J.G.; Guermazi, M. Validation of an Arabic version of the Oswestry index in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 57, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermazi, M.; Mezghani, M.; Ghroubi, S.; Elleuch, M.; Med, A.O.; Poiraudeau, S.; Mrabet, F.; Dammak, J.; Fermanian, J.; Baklouti, S.; et al. The Oswestry index for low back pain translated into Arabic and validated in a Arab population. Ann. Readapt. Med. Phys. 2005, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahdi, A.H. The Arabic Oswestry Disability Index is a Unidimensional Measure: Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Spine 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, K.B.; Kreiner, S.; Mesbah, M. Rasch Models in Health; ISTE-Wiley: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hagquist, C.; Bruce, M.; Gustavsson, J.P. Using the Rasch model in nursing research: An introduction and illustrative example. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrich, D.; Marais, I. A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory: Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, W.J.; Staver, J.R.; Yale, M.S. Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, A.; Conaghan, P.G. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: What is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, T.G.; Fox, C.M. Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J.F.; Tennant, A. An introduction to the Rasch measurement model: An example using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobart, J.C.; Cano, S.J.; Zajicek, J.P.; Thompson, A.J. Rating scales as outcome measures for clinical trials in neurology: Problems, solutions, and recommendations. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, M.; Tennant, A. Patient Reported Outcomes: Misinference from ordinal scales? Trials 2011, 12, A65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, G.N. A Rasch Model for Partial Credit Scoring. Psychometrika 1982, 47, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrich, D.; Sheridan, B.E.; Luo, G. RUMM2030-Professional Edition (Rasch Unidimensional Measurement Model, Version 5.4) [Computer Software]; RUMM Laboratory: Perth, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Andrich, D.A. Category ordering and their utility. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1996, 9, 464. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K.B.; Makransky, G.; Horton, M. Critical Values for Yen’s Q(3): Identification of Local Dependence in the Rasch Model Using Residual Correlations. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2017, 41, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E.V., Jr. Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prinsen, C.A.C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrich, D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 1978, 43, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhard, G. Invariant Measurement: Using Rasch Models in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.M.; Wu, Y.Y.; Hsieh, C.L.; Lin, C.L.; Hwang, S.L.; Cheng, K.I.; Lue, Y.J. Measurement precision of the disability for back pain scale-by applying Rasch analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodke, D.S.; Goz, V.; Lawrence, B.D.; Spiker, W.R.; Neese, A.; Hung, M. Oswestry Disability Index: A psychometric analysis with 1610 patients. Spine J. 2017, 17, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochhead, L.E.; MacMillan, P.D. Psychometric properties of the Oswestry disability index: Rasch analysis of responses in a work-disabled population. Work 2013, 46, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M. Rasch analysis of three versions of the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Man. Ther. 2008, 13, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.J.; Velozo, C.A. The use of Rasch measurement to improve the Oswestry classification scheme. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Shawaryn, M.A.; Cernich, A.N.; Linacre, J.M. Scaling of the revised Oswestry low back pain questionnaire. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | 30.45 ±12.07 |

| Age group | |

| ≤28 years | 57 (50.44) |

| >28 years | 56 (49.56) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 54 (47.8) |

| Female | 59 (52.2) |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.10 |

| Mass (Kg) | 71.54 ±12.14 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) | 25.96 ± 5.61 |

| LBP duration | |

| Acute (<1 month) | 17 (15.04) |

| Subacute (1–3 months) | 19 (16.81) |

| Chronic (>3 months) | 77 (68.14) |

| Radiating pain | |

| Yes | 78 (69.03) |

| No | 35 (30.97) |

| Oswestry Disability Index (0–100) | 25.27 ± 15.38 |

| Run | Analysis | N | Item Fit Residual | Person Fit Residual | Item–Trait Interaction | PSI | Unidimensionality T-Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | χ2 (df) | p | % of Significant Tests | Lower Limit of 95% CI * | ||||

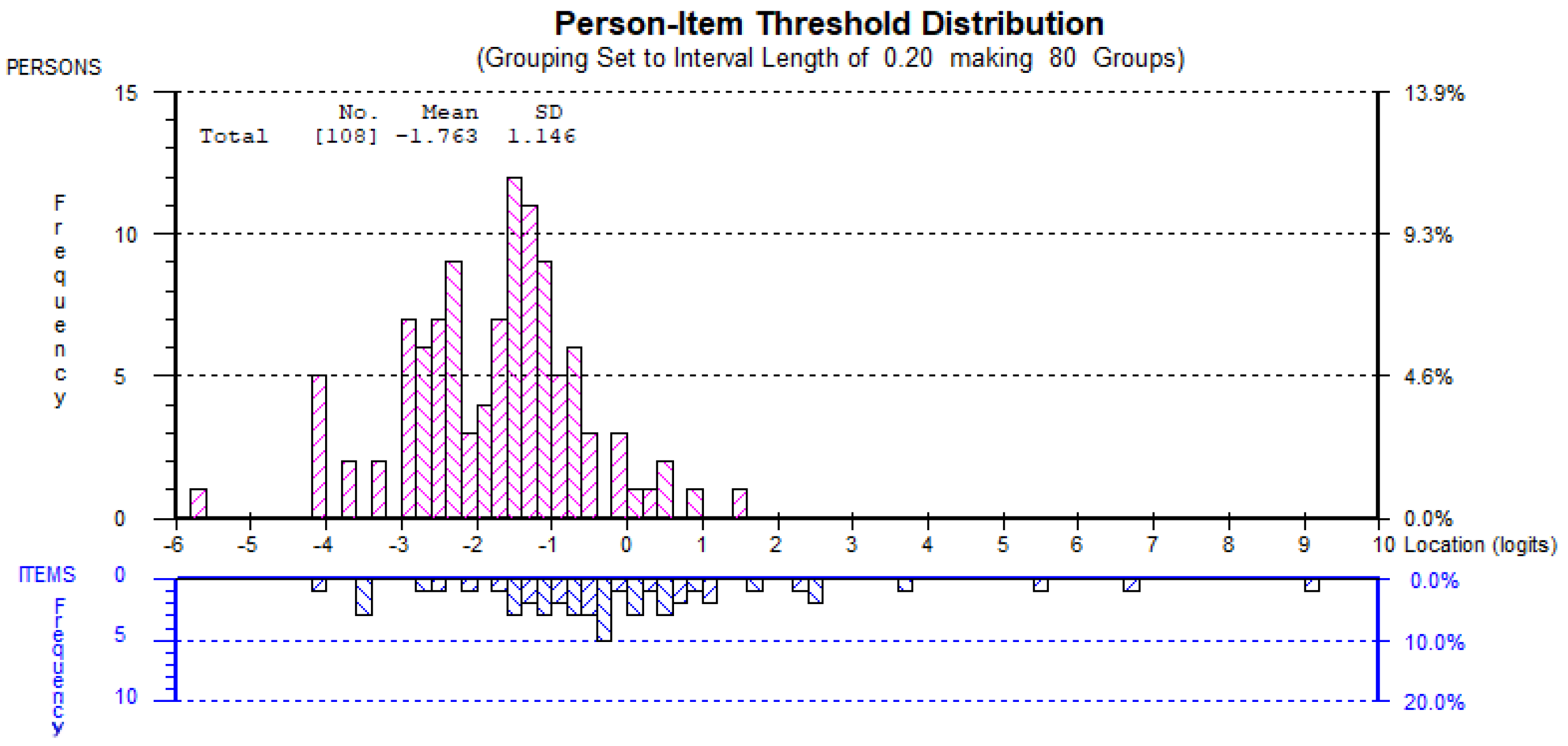

| 1 | Initial analysis | 113 | 0.249 | 1.329 | −0.228 | 1.098 | 26.02 (20) | 0.165 | 0.86 | 8.85% | 4.80% |

| 2 | Delete 4 misfit persons | 109 | 0.205 | 1.26 | −0.193 | 0.973 | 25.94 (20) | 0.168 | 0.85 | 7.34% | 3.20% |

| 3 | Delete 1 misfit person | 108 | 0.191 | 1.242 | −0.187 | 0.945 | 25.32 (20) | 0.189 | 0.85 | 6.48% | 2.40% |

| Item | Location | SE | Fit Residual | χ2 | p | Ordered Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Pain intensity) | −1.15 | 0.10 | 1.46 | 3.01 | 0.22 | ✓ |

| 3 (Lifting) | −1.10 | 0.11 | 0.58 | 3.73 | 0.15 | ✓ |

| 6 (Standing) | −0.83 | 0.11 | 0.56 | 0.12 | 0.94 | ✓ |

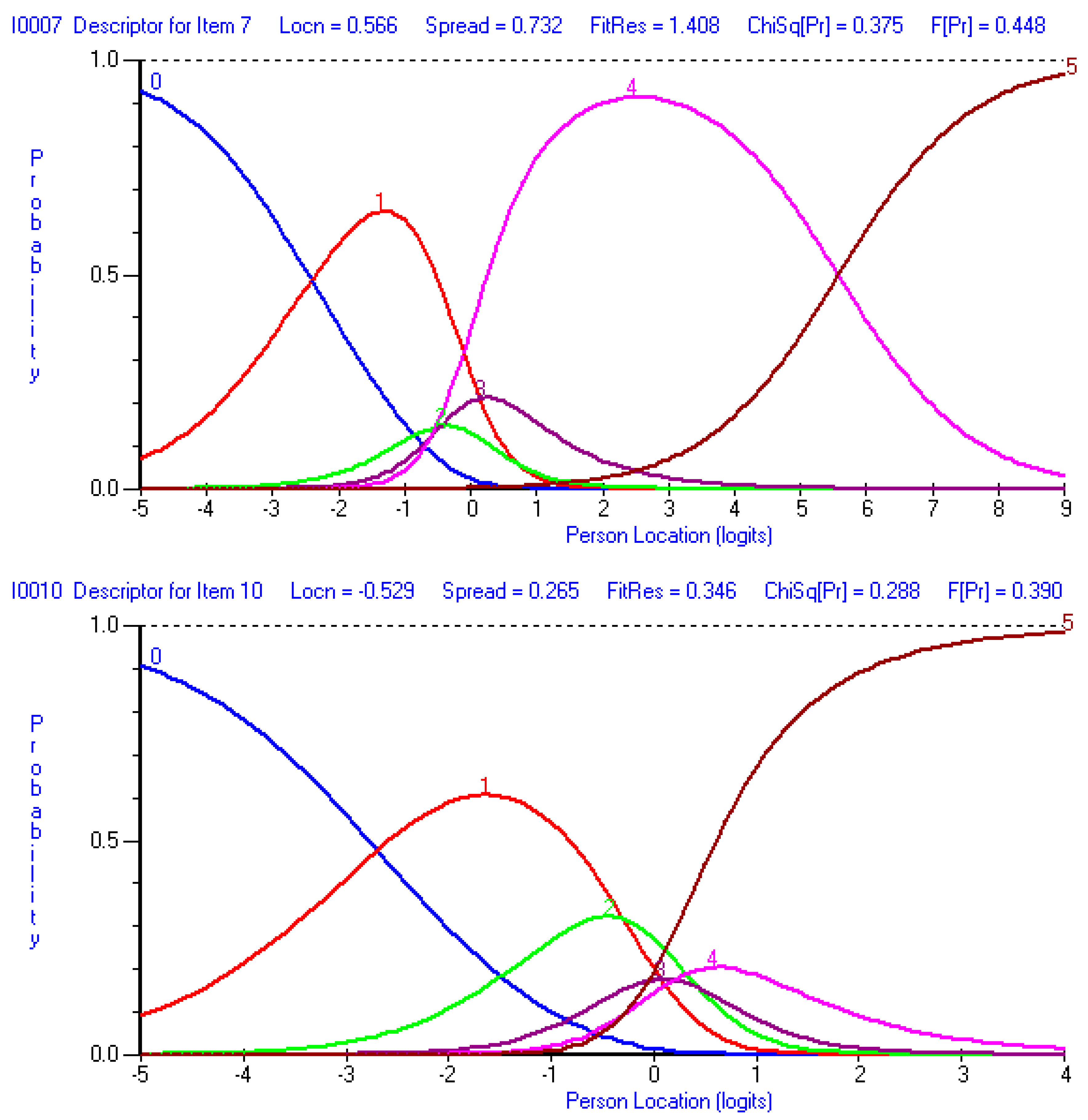

| 10 (Traveling) | −0.53 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 2.49 | 0.29 | × |

| 5 (Sitting) | −0.17 | 0.12 | 1.62 | 1.41 | 0.49 | ✓ |

| 8 (Sex life) | 0.12 | 0.12 | −1.75 | 6.62 | 0.04 | ✓ |

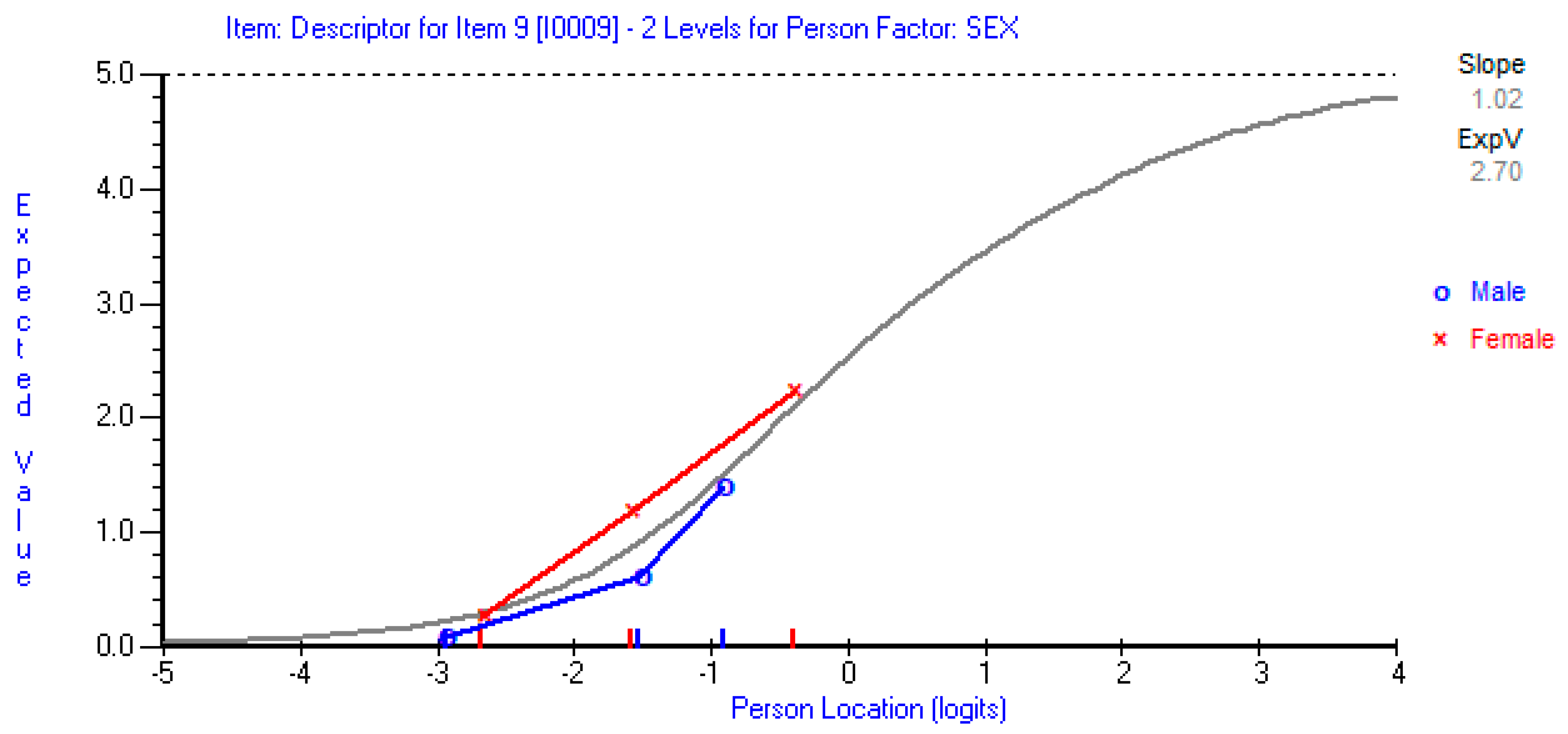

| 9 (Social life) | 0.16 | 0.12 | −1.89 | 3.53 | 0.17 | ✓ |

| 7 (Sleeping) | 0.57 | 0.13 | 1.41 | 1.96 | 0.37 | × |

| 2 (Personal care) | 1.36 | 0.14 | −0.37 | 2.08 | 0.35 | × |

| 4 (Walking) | 1.58 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.37 | 0.83 | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alnahdi, A.H.; Alsubiheen, A.M.; Aldaihan, M.M. Rasch Measurement Model Supports the Unidimensionality and Internal Structure of the Arabic Oswestry Disability Index. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041259

Alnahdi AH, Alsubiheen AM, Aldaihan MM. Rasch Measurement Model Supports the Unidimensionality and Internal Structure of the Arabic Oswestry Disability Index. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(4):1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041259

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlnahdi, Ali H., Abdulrahman M. Alsubiheen, and Mishal M. Aldaihan. 2025. "Rasch Measurement Model Supports the Unidimensionality and Internal Structure of the Arabic Oswestry Disability Index" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 4: 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041259

APA StyleAlnahdi, A. H., Alsubiheen, A. M., & Aldaihan, M. M. (2025). Rasch Measurement Model Supports the Unidimensionality and Internal Structure of the Arabic Oswestry Disability Index. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041259