Acceptability and Palatability of Novel Orodispersible Minitablets of Enalapril in Children up to the Age of 6 with Heart Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Investigational Medicinal Product

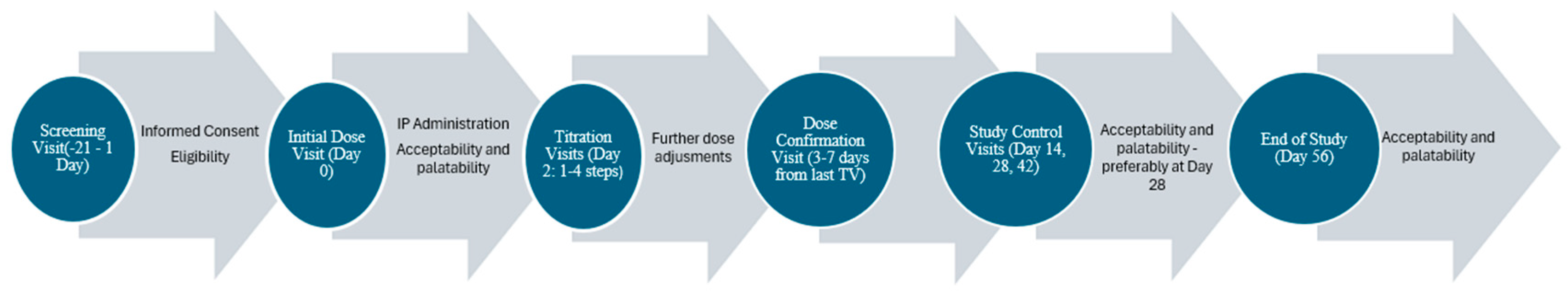

2.4. Study Visits

- Screening Visit (SCRV)—lasting up to 21 days;

- Initiation Visit (IDV)—first ODMT administration;

- Optional Titration Visit(s) (TV)—which could occur up to a maximum of four times;

- Dose Confirmation Visit (DCV);

- Three Study Control Visits (SCV) (at Day 14, Day 28, and Day 42);

- End of Study Visit (EOSV)—Day 56 or the last study visit in case of early termination.

2.5. Acceptability and Palatability Assessments—Evaluation Criteria

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Acceptability and Palatability Assessments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ACEIs | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CHD | Congenital Heart Disease |

| DCM | Dilated Cardiomyopathy |

| DCV | Dose Confirmation Visit |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EOSV | End of Study Visit |

| EU | European Union |

| FSOD | Flexible Solid Oral Dosage |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| HCP | Healthcare Provider |

| IDV | Initiation Visit |

| LENA | Labeling of Enalapril from Neonates up to Adolescents |

| ODMT | Orodispersible Minitablet |

| ODT | Orally Disintegrating Tablet |

| PDCO | Pediatric Committee |

| PIP | Pediatric Investigational Plan |

| SCV | Study Control Visit |

| SCRV | Screening Visit |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SmPC | Summary of Product Characteristics |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TV | Titration Visit |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Castaldi, B.; Cuppini, E.; Fumanelli, J.; Di Candia, A.; Sabatino, J.; Sirico, D.; Vida, V.; Padalino, M.; Di Salvo, G. Chronic Heart Failure in Children: State of the Art and New Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, J.B.; Garcia, A.M.; Jacobsen, R.M.; Miyamoto, S.D. Important Considerations in Pediatric Heart Failure. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajcetic, M.; Jelisavcic, M.; Mitrovic, J.; Divac, N.; Simeunovic, S.; Samardzic, R.; Gorodischer, R. Off Label and Unlicensed Drugs Use in Paediatric Cardiology. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 61, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocchi, F.; Tomasi, P. The Development of Medicines for Children: Part of a Series on Pediatric Pharmacology, Guest Edited by Gianvincenzo Zuccotti, Emilio Clementi, and Massimo Molteni. Pharmacol. Res. 2011, 64, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccari, G.; Alfei, S.; Marimpietri, D.; Iurilli, V.; Barabino, P.; Marchitto, L. Mini-Tablets: A Valid Strategy to Combine Efficacy and Safety in Pediatrics. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jîtcă, C.-M.; Jîtcă, G.; Ősz, B.-E.; Pușcaș, A.; Imre, S. Stability of Oral Liquid Dosage Forms in Pediatric Cardiology: A Prerequisite for Patient’s Safety—A Narrative Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, W.A.; AlRafayah, E.; AlHazabreh, M.; AbuLaila, S.; Al-Ghananeem, A.M. Formulation Challenges and Strategies to Develop Pediatric Dosage Forms. Children 2022, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppu, K. Paediatric Clinical Pharmacology—At the Beginning of a New Era. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 64, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairuz, T.E.; Gargiulo, D.; Bunt, C.; Garg, S. Quality, Safety and Efficacy in the ‘Off-Label’ Use of Medicines. Curr. Drug Saf. 2008, 2, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehr, C.; Richardson, J.; Bint, L.; Parsons, R.; Sunderland, B.; Czarniak, P. Cross-Sectional Survey of off-Label and Unlicensed Prescribing for Inpatients at a Paediatric Teaching Hospital in Western Australia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajcetic, M.; Kearns, G.; Jovanovic, I.; Brajovic, M.; van den Anker, J. Availability of Oral Formulations Labeled for Use in Young Children in Serbia, Germany and the USA. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 5668–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.; Forte, G.; Trapsida, J.M.; Hill, S. What Essential Medicines for Children Are on the Shelf? Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency Revised Priority List for Studies on Off-Patent Paediatric Medicinal Products. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/revised-priority-list-studies-patent-paediatric-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Münch, J.; Kloft, C.; Farhan, M.; Fishman, V.; Leng, S.; Bosse, H.M.; Klingmann, V. Acceptability, Swallowability, Palatability, and Safety of Multiple Film-Coated Mini-Tablets in Children Aged ≥2–<7 Years: Results of an Open-Label Randomised Study. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines: Report of the WHO Expert Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1006. [Google Scholar]

- Kozarewicz, P. Regulatory Perspectives on Acceptability Testing of Dosage Forms in Children. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 469, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Expert Committee Annex 5 Development of Paediatric Medicines: Points to Consider in Formulation; Technical Reports No. 970 2012, Forthy-Six; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Comoglu, T. Formulation and Evaluation of Carbamazepine Fast Disintegrating Tablets. Die Pharm. Ind. 2010, 72, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Comoglu, T.; Dilek Ozyilmaz, E. Orally Disintegrating Tablets and Orally Disintegrating Mini Tablets–Novel Dosage Forms for Pediatric Use. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2019, 24, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orubu, E.S.F.; Tuleu, C. Medicines for Children: Flexible Solid Oral Formulations. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingmann, V. Acceptability of Mini-Tablets in Young Children: Results from Three Prospective Cross-over Studies. AAPS Pharmscitech 2017, 18, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thabet, Y.; Slavkova, M.; Breitkreutz, J. 10 Years EU Regulation of Pediatric Medicines–Impact on Cardiovascular Drug Formulations. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2018, 15, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.A.; Tuleu, C.; Wong, I.C.K.; Keady, S.; Pitt, K.G.; Sutcliffe, A.G. Minitablets: New Modality to Deliver Medicines to Preschool-Aged Children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e235–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingmann, V.; Spomer, N.; Lerch, C.; Stoltenberg, I.; Frömke, C.; Bosse, H.M.; Breitkreutz, J.; Meissner, T. Favorable Acceptance of Mini-Tablets Compared with Syrup: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Infants and Preschool Children. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1728–1732.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingmann, V.; Seitz, A.; Meissner, T.; Breitkreutz, J.; Moeltner, A.; Bosse, H.M. Acceptability of Uncoated Mini-Tablets in Neonates—A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 893–896.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsui, N.; Hida, N.; Kamiya, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Saito, K.; Saito, J.; Yamatani, A.; Ishikawa, Y.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Swallowability of Minitablets among Children Aged 6–23 Months: An Exploratory, Randomized Crossover Study. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spomer, N.; Klingmann, V.; Stoltenberg, I.; Lerch, C.; Meissner, T.; Breitkreutz, J. Acceptance of Uncoated Mini-Tablets in Young Children: Results from a Prospective Exploratory Cross-over Study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijelic, M.; Djukic, M.; Vukomanovic, V.; Parezanovic, V.; Lazic, M.; Pavlovic, A.; Popovic, S.; Parezanovic, M.; Stefanovic, I.; Djordjevic, S.; et al. Clinical and Hemodynamic Outcomes with Enalapril Orodispersible Minitablets in Young Children with Heart Failure Due to Congenital Heart Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajcetic, M.; de Wildt, S.N.; Dalinghaus, M.; Breitkreutz, J.; Klingmann, I.; Lagler, F.B.; Keatley-Clarke, A.; Breur, J.M.; Male, C.; Jovanovic, I.; et al. Orodispersible Minitablets of Enalapril for Use in Children with Heart Failure (LENA): Rationale and Protocol for a Multicentre Pharmacokinetic Bridging Study and Follow-up Safety Study. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2019, 15, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecken, A.; Burckhardt, B.B.; Khalil, F.; de Hoon, J.; Klingmann, I.; Herbots, M.; Laeer, S.; Lagler, F.B.; Breitkreutz, J. Relative Bioavailability of Enalapril Administered as Orodispersible Minitablets in Healthy Adults. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2020, 9, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluk, A.; Sznitowska, M.; Brandt, A.; Sznurkowska, K.; Plata-Nazar, K.; Mysliwiec, M.; Kaminska, B.; Kotlowska, H. Can Preschool-Aged Children Swallow Several Minitablets at a Time? Results from a Clinical Pilot Study. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 485, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Kirby, D.; Bryson, S.; Shah, M.; Rahman Mohammed, A. Paediatric Specific Dosage Forms: Patient and Formulation Considerations. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 616, 121501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarini, A.; Bianchetti, A.A.; Fossali, E.F.; Faré, P.B.; Simonetti, G.D.; Lava, S.A.G.; Bianchetti, M.G. What Can We Do to Make Antihypertensive Medications Taste Better for Children? Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 457, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgraggen, L.; Faré, P.B.; Lava, S.A.G.; Simonetti, G.D.; Fossali, E.F.; Amoruso, C.; Bianchetti, M.G. Palatability of Crushed β-Blockers, Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Thiazides. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2012, 37, 544–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golhen, K.; Buettcher, M.; Kost, J.; Huwyler, J.; Pfister, M. Meeting Challenges of Pediatric Drug Delivery: The Potential of Orally Fast Disintegrating Tablets for Infants and Children. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejeta, F. Recent Formulation Advances and Preparation of Orally Disintegrating Tablets. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2022, 26, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Omidian, H.; Mfoafo, K. Exploring the Potential of Nanotechnology in Pediatric Healthcare: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 Everything swallowed | No residue found during oral inspection |

| 2 Partially swallowed | No direct swallowing or residue found during oral inspection |

| 3 Choked on | ODMT was inhaled or caused coughing |

| 4 Termination | The procedure was discontinued on the decision of the assessor, a parent or the patient |

| Criterion | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 Everything swallowed | No chewing during deglutition and no residue found during oral inspection |

| 2 Chewed/Partially swallowed | Chewing observed and/or majority of the tablet pieces swallowed, but small residue found during oral inspection |

| 3 Spat out | Spat out |

| 4 Inhaled/coughed | ODMT was inhaled or caused coughing |

| 5 Refused to take | Not allowing the investigator to place ODMT in mouth |

| Criterion | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pleasant | Positive hedonic pattern |

| 2 | No change | Neutral |

| 3 | Unpleasant | Negative aversive pattern |

| Acceptability | Palatability | ODMT Dose | Beverage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everything swallowed | Partially swallowed | Pleasant | No change | Unpleasant | 0.25 mg | 1 mg | Yes | No | |

| IDV | 32 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 4 | 52 | 6 | 11 | 47 |

| SCV | 40 | 19 | 35 | 22 | 2 | 51 | 8 | 6 | 53 |

| EOSV | 39 | 13 | 32 | 20 | 0 | 44 | 8 | 5 | 47 |

| Relation Between: | Chi-Square |

|---|---|

| |

| Age group, IDV | χ2 (1, N = 58) = 4.852 p = 0.028 |

| Age group, SCV | χ2 (1, N = 59) = 4.473 p = 0.034 |

| HF etiology, SCV | χ2 (1, N = 59) = 3.773 p = 0.052 (borderline) |

| Pretreatment, EOSV | χ2 (1, N = 52) = 5.778 p = 0.016 |

| |

| Age group, IDV | χ2 (1, N = 58) = 4.826 p = 0.028 |

| HF etiology, IDV | χ2 (1, N = 58) = 7.269 p = 0.007 |

| Pretreatment, SCV | χ2 (1, N = 59) = 5.207 p = 0.022 |

| Pretreatment, EOSV | χ2 (1, N = 52) = 13.268 p = 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazic, M.; Djukic, M.; Vukomanovic, V.; Bijelic, M.; Obarcanin, E.; Bajcetic, M. Acceptability and Palatability of Novel Orodispersible Minitablets of Enalapril in Children up to the Age of 6 with Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14030915

Lazic M, Djukic M, Vukomanovic V, Bijelic M, Obarcanin E, Bajcetic M. Acceptability and Palatability of Novel Orodispersible Minitablets of Enalapril in Children up to the Age of 6 with Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(3):915. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14030915

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazic, Milica, Milan Djukic, Vladislav Vukomanovic, Maja Bijelic, Emina Obarcanin, and Milica Bajcetic. 2025. "Acceptability and Palatability of Novel Orodispersible Minitablets of Enalapril in Children up to the Age of 6 with Heart Failure" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 3: 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14030915

APA StyleLazic, M., Djukic, M., Vukomanovic, V., Bijelic, M., Obarcanin, E., & Bajcetic, M. (2025). Acceptability and Palatability of Novel Orodispersible Minitablets of Enalapril in Children up to the Age of 6 with Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(3), 915. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14030915