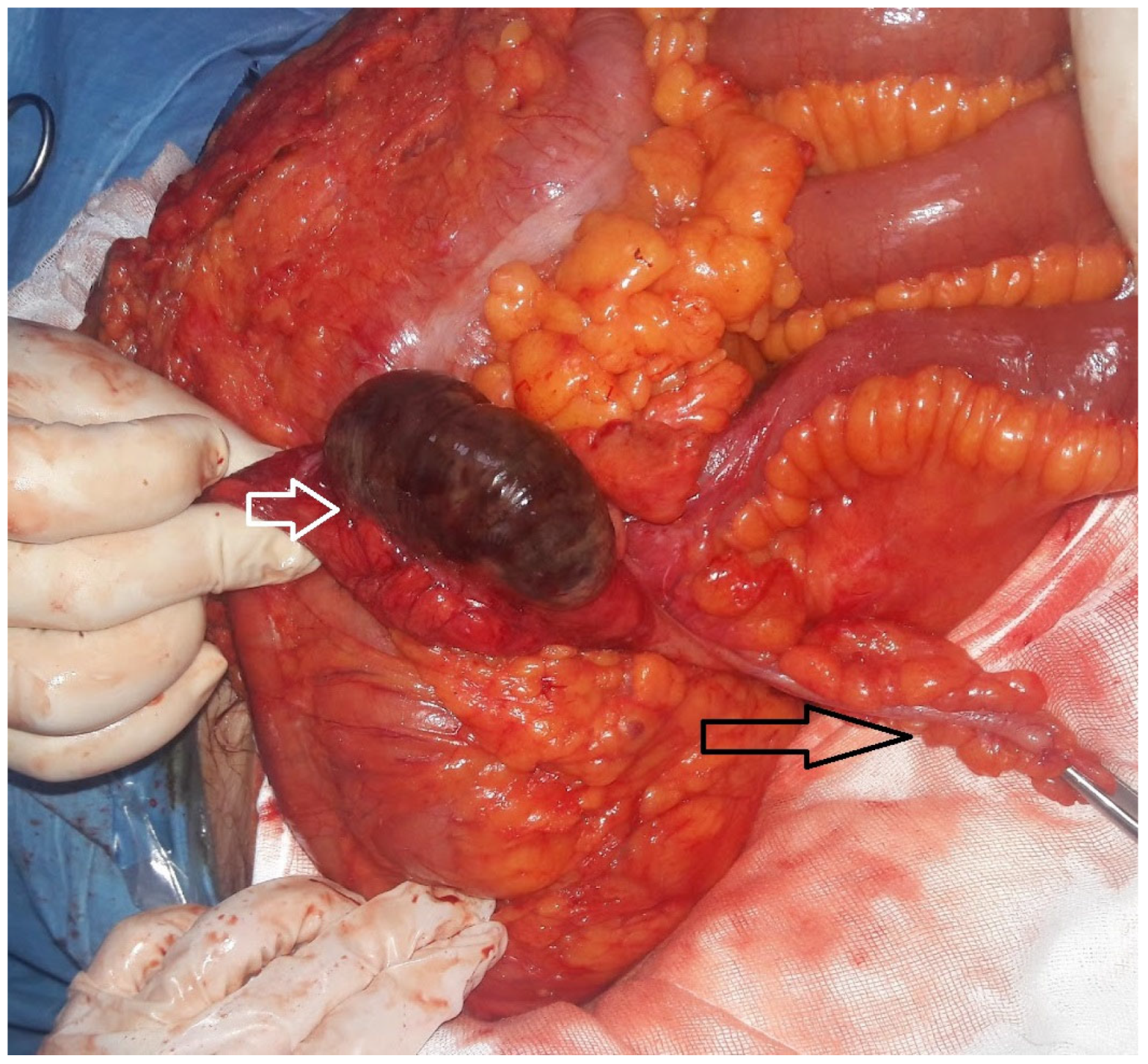

Isolated Cecal Necrosis as a Cause of Acute Abdomen

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICN | Isolated cecum necrosis |

| ADPKD | Autosomal Polycystic Kidney Disease |

| AVF | Arteriovenous fistula |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CRF | Chronic renal failure |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| CVA | Cerebrovascular accident |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| F | Female |

| g/dL | Gram per deciliter |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HCT | Hematocrit |

| HT | Hypertension |

| L | Liter |

| M | Male |

| mcL | Microliter |

| PLT | Platelet |

| RLQ | Right lower quadrant pain |

| TAH | The Artificial Heart |

| USG | Ultrasonography |

| WBC | White blood |

References

- Kohga, A.; Yajima, K.; Okumura, T.; Yamashita, K.; Isogaki, J.; Suzuki, K.; Komiyama, A.; Kawabe, A. A Case of Isolated Cecal Necrosis Preoperatively Diagnosed with Perforation of Cecum. Medicina 2019, 55, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirican, A.; Unal, B.; Bassulu, N.; Tatlı, F.; Aydin, C.; Kayaalp, C. Isolated Cecal Necrosis Mimicking Acute Appendicitis: A Case Series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2009, 3, 7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çakar, E.; Ersöz, F.; Bag, M.; Bayrak, S.; Çolak, Ş.; Bektaş, H.; Güneş, M.E.; Çakar, E. Isolated cecal Necrosis: Our Surgical Experience and a Review of the Literature. Turk. J. Surg. 2014, 30, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuler, J.G.; Hudlin, M.M. Cecal Necrosis: Infrequent variant of ischemic colitis. Report of five cases. Dis. Colon Rectum 2000, 43, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahverdi, E.; Morshedi, M.; Oraei-Abbasian, F.; Allahverdi Khani, M.; Khodayarnejad, R. A Rare Case of Vasculitis Patched Necrosis of Cecum due to Behçet’s Disease. Case Rep. Surg. 2017, 2017, 1693737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suleimanov, V.; Shahzad, F. Partial Infarction of Cecal Wall Presenting as Acute Appendicitis. Cureus 2022, 14, e31408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janike, K.; Pan, A.; Kheirkhah, P.; Shuja, A. Isolated Cecal Necrosis Mimicking a Colonic Mass. ACG Case Rep. J. 2023, 10, e01030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Rex, D.K.; Zhang, D. Mass-forming isolated ischemic necrosis of the cecum mimicking malignancy: Clinicopathologic features of 11 cases. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2024, 75, 152428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabay, O.; Erdem, M.; Hasbahceci, M. Partial Cecum Necrosis as a Rare Cause of Acute Abdominal Pain in an Elderly Patient. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2018, 28, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N.H.H.L.; Rafiee, H.; Beales, I.L.P.; Karthigan, R.; Ciorra, A.; Kim, T. Isolated caecal necrosis—A case study. BJR Case Rep. 2018, 5, 20180089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyvaz, K.; Sıkar, H.E.; Gökçeimam, M.; Küçük, H.F.; Kurt, N. A rare cause of acute abdomen: A rare cause of acute abdomen: Isolated necrosis of the cecum. Turk. J. Surg. 2020, 36, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Gamallo, C. Ischaemic caecal necrosis. Acta Chir. Belg. 2008, 108, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rist, C.B.; Watts, J.C.; Lucas, R.J. Isolated ischemic necrosis of the cecum in patients with chronic heart disease. Dis. Colon Rectum 1984, 27, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.P.; Saratzis, A.; Zayyan, K. Spontaneous, Isolated Caecal Necrosis: Report of a Case, Review of the Literature, and Updated Classification. Acta Chir. Belg. 2013, 113, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardoun, N.; Hadrich, Z.; Rahma, D.; Harbi, H.; Boujelben, S.; Mzali, R. Isolated cecal necrosis: Report of two cases. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, 04552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundes, E.; Kucukkartallar, T.; Çolak, M.; Cakir, M.; Aksoy, F. Ischemic Necrosis of the Cecum: A Single Center Experience. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 61, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atıcı, S.D.; Ustun, M.; Kuzey, A.E.; Kaya, T.; Çalık, B. A rare cause of right lower quadrant abdominal pain: Isolated Cecal necrosis. Turk. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 32, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sunamak, O.; Corbaci, K.; Akyuz, C.; Gul, M.O.; Besler, E.; Donmez, T.; Ekiz, F. Isolated cecum necrosis: Single center experience in the light of literature. In Proceedings of the 23th National Surgery Congress, Antalya, Turkey, 24–28 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

| The number of patients | 7 |

| Age (median and range) | 61 (36–67) |

| M/F ratio | 5/2 |

| Symptoms | |

| Pain | 7/7 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3/7 |

| Symptom duration (days) (median and range) | 1 (1–4) |

| Prediagnosis | |

| Acute abdomen | 5/7 |

| Acute appendicitis | 2/7 |

| Chronic Disease | 6/7 |

| CRF | 4/7 |

| DM | 2/7 |

| CAD | 2/7 |

| HT | 2/7 |

| ADPKD | 1/7 |

| CVA | 1/7 |

| TAH | 1/7 |

| None | 1/7 |

| Ejection fraction (%) (6/7) | 60 |

| Dialysis treatment | 4/7 |

| AVF | 4/7 |

| USG | 2/7 |

| USG findings | Intra-abdominal free fluid |

| Findings consistent with acute appendicitis | |

| CT | 4/7 |

| CT findings | |

| Non-specific | 2/7 |

| Air in the bowel wall | 1/7 |

| Increase in thickness of the cecum wall | 2/7 |

| Perforation | 3/7 |

| The interval between the beginning of the symptoms and surgery (Day) (median and range) | 1 (1–4) |

| Incision | |

| Midline laparotomy | 5/7 |

| McBurney | 2/7 |

| Surgical procedure | |

| Right hemi-colectomy + anastomosis | 4/7 |

| Right hemi-colectomy + end ileostomy | 5/7 |

| Hematoma drainage | 1/7 |

| Conversion to end ileostomy | 2/7 |

| Mortality | 1/7 |

| Hospital stay (day) (median and range) | 12 (4–16) |

| 30-day mortality | 1/7 |

| Perforation | Non-Perforation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | 1 | 4 |

| F | 2 | 0 | |

| Age (median) | 61 | 61.5 | |

| Abdominal Pain | 3 | 4 | |

| Nausea–Vomiting | 1 | 2 | |

| CRF | 2 | 2 | |

| CAD | 1 | 1 | |

| DM | 1 | 1 | |

| HT | 0 | 2 | |

| CVA | 1 | 0 | |

| TAH | 1 | 0 | |

| ADPKD | 0 | 1 | |

| Surgery | Ileostomy | 2 | 1 |

| Anastomosis | 1 | 3 | |

| 2nd Operation | Ileostomy | - | 1 |

| 3rd Operation | Ileostomy | - | 1 |

| Mortality | 0 | 1 | |

| WBC (×109/L) | 16.783 | 12.8525 | |

| NEUT (mcL) | 14.61 | 11.4975 | |

| WBC/NEUT | 1.187 | 1.077 | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 11.53 | 12.9 | |

| HCT (%) | 37.2 | 39.875 | |

| PLT (/mcL) | 324,000 | 212,000 |

| Study/ (Peri-Operative Mortality) | Number (M/F) | Age (Years) | Symptom | Symptom Duration (Day) | WBC Count (/mm3) | US | CT Imaging | Colonoscopy | Comorbidity | Preliminary Diagnosis | Incision | Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rist 1984 (0) | 3 (M) | 79 (59–84) | 3xPain, 2xNausea, Vomiting | - | 16.000 (12.600–18.100) | - | - | - | 3xCHF, 2xCVD (Digoxin) 1xCVA | 2xAcute abdomen 2xAcute appendicitis | - | 2xRight hemicolectomy 1 Cecectomy |

| Schuler 2000 (1/5) | 5 (1/4) | 84 (57–91) | 5xPain, 1xNausea/ Vomiting, 1x Diarrhea | 1 (0.3–3) | 17.000 (12.000–20.600) | - | - | - | 2xHT 1xDM 1XCABG 1xCAD 1xCHF | Acute appendicitis Acute abdomen Cecum cancer | - | 4xRight hemicolectomy +anastomosis 1xRight hemicolectomy +end ileostomy |

| Ruiz-Tovar 2008 (0) | 1F | 82 | Pain | 4 | 8.100 | - | Asymmetric thickening of the caecal wall, suggesting a caecal neoplasm | Cecum tumor | Midline laparotomy | Right hemicolectomy +anastomosis | ||

| Dirican 2009 (0) | 4 (2/2) | 59 (46–68) | 4xPain 4xNausea/ Vomiting | 20.200 (16.400–23.700) | 3xFree intra abdominal fluid | 1xNon-specific | - | 2xCRF 1xCRF+DM+HT 1xCOPD | Acute appendicitis | 1xDiagnostic laparoscopy 3xLaparotomy | 3xRight hemicolectomy +anastomosis 1xCecum resection +ileostomy | |

| Gundes 2013 (5/13) | 13 (8/5) | 68 (51–84) | 13xPain 8xDistention, 8xVomiting | 3 (1–7) | 15.200 (8.700–29.000) | 5xFluid in the right lower quadrant and contamination in the fatty planes 3x Normal | 2xThickening and inflammation in the cecal wall | - | 5xCRF 3xHT 2xAF 2xDM 1xCOPD 1xFMF 1xCAD 1xCVA | Acute appendicitis | - | 10xRight hemicolectomy 2xRight hemicolectomy +end ileostomy 1xCecal resection |

| Hunter 2013 (0) | 1F | 74 | Pain Nausea | 0.25 | 12.030 | - | - | HT Diverticulosis | - | Diagnostic laparoscopy +Midline laparotomy | Partial cecum resection | |

| Çakar 2014 (5/6) | 6 (3/3) | 60.3 (38–85) | Pain Vomiting | - | - | 1xAir-fluid level (out of 4) | - | 4xCRF 4xDM 4xHT 1xAF+CAB 1xAortabifemo- ral graft | Acute appendicitis | 1xDiagnostic laparoscopy Laparatomy | 2xRight hemicolectomy +end ileostomy + mucous fistula 2xRight hemicolectomy +anastomosis 1xCecal resection +anastomosis+ 1xCecal resection +end ileostomy + mucous fistula 3xReoperation 2xEnd ileostomy+mucous fistula 1xRight hemicolectomy +end ileostomy +mucous fistula | |

| Shahverdi 2017 (0) | 1 (F) | 62 | Pain Nausea Vomiting | - | 9.700 | Dilated bowels with abundant gas | A minor fluid collection in right lower quadrant | - | DM, HT, CAD, CVA, CABG Behçet’s disease | Acute abdomen | Midline | Right hemicolectomy + anastomosis |

| Karabay 2018 (0) | 1 (F) | 68 | Pain | 7 | 15.390 | Non specific | Linear density at the back of the cecum and a tubular structure extending to the liver | - | DM, HT | Acute appendicits | Laparoscopy +open surgery | Partial cecum resection +anastomosis |

| Kohga 2018 (0) | 1 (M) | 59 | Pain | 0.2 | 8.700 | - | A dilated cecum surrounded by free air | - | AF, digoxin | Cecum perforation | Diagnostic laparosocpy | 1xLaparoscopic assisted ileocecal resection +anastomosis 1xIleostomy |

| Chan 2018 (0) | 1 (F) | Pain Nausea Vomiting/ and Diarrhea. | 10.000 | - | Focal cecum ischemia and chronic SMA stenosis | Cecal ulcer and ischemic mucosa | AF, HT, CRF | Cecum ischemia | - | Medical treatment | ||

| Eyvaz 2020 (0) | 1 (F) | 76 | Pain, Nausea | 0.5 | 16.200 | - | Thickening on the cecum wall | - | TBC Thyroidectomy HT | Acute abdomen, Acute appendicitis | Midline | Ileocecal resection +anastomosis |

| Kardoun 2021 (0) | 2 (F) | 72 (66–78) | 2xPain 1xNausea/ Vomiting | - | 12.850 (11.600–14.100) | - | 1xDilated cecum with mural thickening, edema, and intramural gas (pneumatosis), portal venous gas and mesenteric gas while (appendix normal) 1xCecum surrounded by free air, (appendix normal) | 2xCRF 2xHT 1xCAD 1xDyslipidemia 2xDM 1xAF (Digoxin) | Cecum ischemia | Midline laparotomy | 1xCecum resection +anastomosis 1xIleocecal resection + a double-barrel ileocolostomy | |

| Atıcı 2022 (6) | 17 (9/8) | 56 (22–85) | 17xPain 17xNausea | 1 | 17xPericecal inflammation and cecal wall thickening | 4xCRF 5xCAD 8xHT 3xCHF 5xArrhytmia 4xDM 3xCOPD 1xChronic pancreatitis 1xLung cancer 1xIliac artery stent 1x Aplastic anemia | 2xDiagnostic laparoscopy 17xMidline | 14xRight hemicolectomy +anastomosis 2xRight hemicolectomy +Mikulicz ileocolostomy 1xPartial cecum resection +Mikulicz ileocolostomy | ||||

| Suleimanov 2022 (0) | 1 (M) | 42 | Pain Nausea/ Vomiting | 3 | 16.000 | Unremarkable | - | - | Acute appendicitis | McBurney +extension | Ileocecal resection +anastomosis | |

| Janike 2023 (0) | 1F | 77 | Pain Nausea Vomiting Melena Wigth loss | Several days | 13.000 | - | Colonic mass | Cecal ischemic mass | HT Hyperlipidemia Obesity | ICN | Laparotomy | Right hemicolectomy + anastomosis |

| Liao 2025 (0) | 11 (4/7) | 72 (43–87) | 6xPain 5xGI bleeding 3xDiarrhea 4xNausea/ Vomiting 2xAsymptomatic (screening colonoscopy) | - | - | - | 8xColonic mass (out of 9)m (pathology ischemia) | 9x Colonic mass (out of 9) | 7xHT 5xCVD 4xHyper-lipidemia 2xCOPD 2xDM 1xCRF | ICN | 5x Laparotomy | 6xMedical Treatment 5xRight hemicolectomy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sunamak, O.; Corbaci, K.; Akyuz, C.; Gul, M.O.; Besler, E.; Donmez, T.; Ekiz, F. Isolated Cecal Necrosis as a Cause of Acute Abdomen. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031019

Sunamak O, Corbaci K, Akyuz C, Gul MO, Besler E, Donmez T, Ekiz F. Isolated Cecal Necrosis as a Cause of Acute Abdomen. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(3):1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031019

Chicago/Turabian StyleSunamak, Oguzhan, Kadir Corbaci, Cebrail Akyuz, Mehmet Onur Gul, Evren Besler, Turgut Donmez, and Feza Ekiz. 2025. "Isolated Cecal Necrosis as a Cause of Acute Abdomen" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 3: 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031019

APA StyleSunamak, O., Corbaci, K., Akyuz, C., Gul, M. O., Besler, E., Donmez, T., & Ekiz, F. (2025). Isolated Cecal Necrosis as a Cause of Acute Abdomen. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(3), 1019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14031019