Feasibility and Safety of an Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Pilot Validation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Age ≥ 18 years at enrollment.

- Diagnosis of CVD, including acute coronary syndrome or stable ischemic heart disease after percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting; valvular heart disease with valve replacement surgery; stable heart failure; or prior cardiac surgery.

- Classified as low-to-moderate exercise risk for supervised exercise and exercise testing based on institutional assessment.

- Ability to understand study procedures and provide written informed consent.

- Physical ability to mount and pedal a cycle and perform symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Absolute contraindications to exercise testing or training per established exercise testing guidelines [15].

- Hemodynamically unstable conditions (e.g., acute infection or severe electrolyte imbalance) or uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg at rest that could not be safely controlled before testing).

- Severe or uncontrolled arrhythmia or the presence of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) for whom device management could not ensure safety during supervised exercise.

- Recent acute myocardial infarction (MI), unstable coronary syndrome, or major cardiac procedure within the acute post-event period (patients within the first 2 weeks after an acute MI were excluded).

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <30% or New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV symptoms.

- Severe cognitive impairment or psychiatric disorder that, in the investigator’s judgment, prevented informed consent or safe participation.

- Significant musculoskeletal, neurologic, or other lower-extremity conditions that prevent safe cycling or valid CPET

- Inability to ambulate or transfer safely for cycle mounting or dismounting without reasonable assistance

- Other comorbid conditions expected to significantly limit life expectancy or interfere with participation, as judged by the investigator.

2.4. Study Protocol

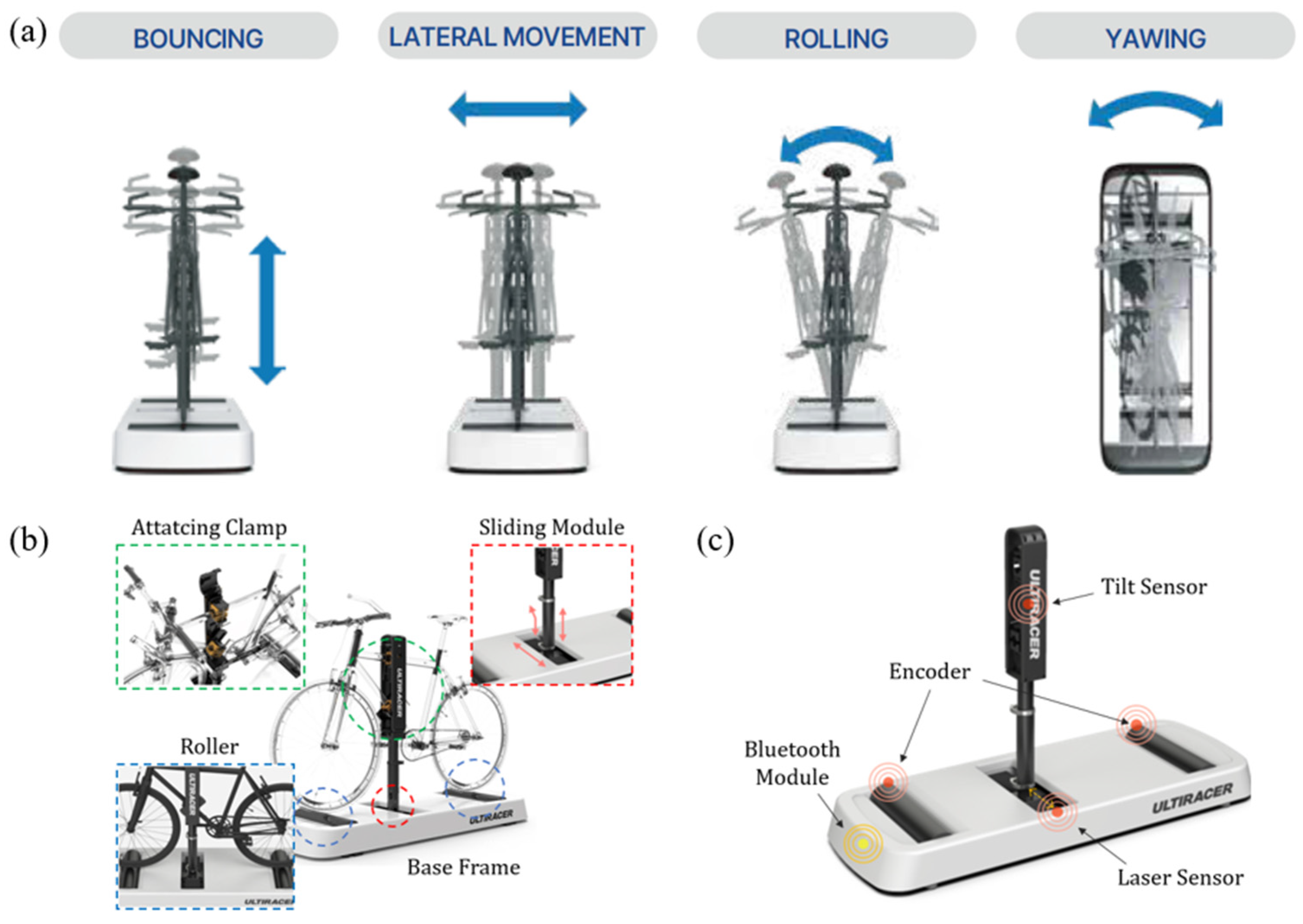

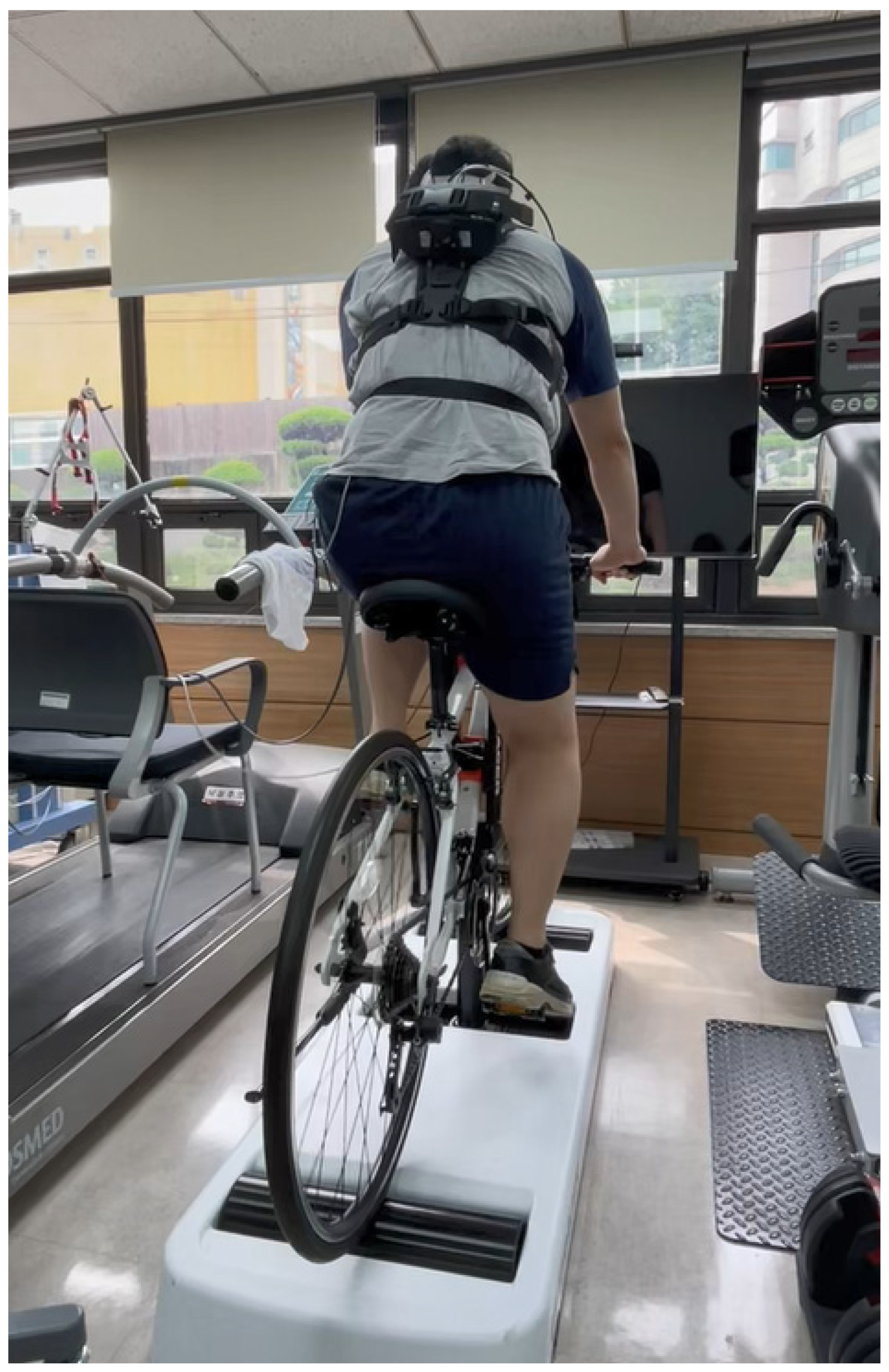

2.5. An Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device

2.6. Outcome Measurements

2.6.1. Assessment of Cardiopulmonary Responses

2.6.2. Assessment of Body Composition

2.6.3. Assessment of Physical Activity Level

2.6.4. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life

2.6.5. Assessment of Muscle Strength

2.6.6. Assessment of Exercise Capacity

2.6.7. Patient Satisfaction Assessment with Outdoor-Simulated Indoor Cycling Device

2.7. Safety Monitoring

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Assessment of Participants

3.2. Comparison of Cardiopulmonary Responses Between the Treadmill and the Cycling Device

3.3. Subgroup Analysis Regarding the Comparison of Cardiopulmonary Responses Between the Treadmill and the Cycling Device

3.4. Adverse Events

3.5. Patient Satisfaction with the Novel Cycling Device

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CR | Cardiac rehabilitation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise stress test |

| VO2 | Oxygen consumption |

| HR | Heart rate |

| METs | Metabolic equivalents |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| ICD | Implantable cardioverter defibrillator |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| STEMI | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| SMI | Skeletal muscle mass index |

| KASI | Korean activity scale index |

| EQ-5D | EuroQol-5 Dimension |

| 6MWT | 6 min walk test |

| VT | Ventilatory threshold |

| RER | Respiratory exchange ratio |

| RPP | Rate–pressure product |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| VCO2 | Carbon dioxide output |

| VE | Ventilatory equivalent |

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases. 11 June 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Anderson, L.; Oldridge, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Rees, K.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation for Coronary Heart Disease: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibben, G.O.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Arena, R.; Franklin, B.; Pina, I.; Kraus, W.E.; McInnis, K.; Balady, G.J. Recommendations for clinical exercise laboratories: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2009, 119, 3144–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noseworthy, M.; Peddie, L.; Buckler, E.J.; Park, F.; Pham, M.; Pratt, S.; Singh, A.; Puterman, E.; Liu-Ambrose, T. The Effects of Outdoor versus Indoor Exercise on Psychological Health, Physical Health, and Physical Activity Behaviour: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peddie, L.; Gosselin Boucher, V.; Buckler, E.J.; Noseworthy, M.; Haight, B.L.; Pratt, S.; Injege, B.; Koehle, M.; Faulkner, G.; Puterman, E. Acute effects of outdoor versus indoor exercise: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2024, 18, 853–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redberg, R.F.; Vittinghoff, E.; Katz, M.H. Cycling for Health. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Bauman, A.; de Geus, B.; Krenn, P.; Reger-Nash, B.; Kohlberger, T. Health benefits of cycling: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikpeze, T.C.; Glaun, G.; McCalla, D.; Elfar, J.C. Geriatric Cyclists: Assessing Risks, Safety, and Benefits. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2018, 9, 2151458517748742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, I.J.; Cho, Y.M.; Cho, S.J.; Yeom, S.R.; Park, S.W.; Kim, S.E.; Yoon, J.C.; Kim, Y.; Park, J. Prediction of Severe Injury in Bicycle Rider Accidents: A Multicenter Observational Study. Emerg. Med. Int. 2022, 2022, 7994866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanschik, D.; Bruno, R.R.; van Genderen, M.E.; Serruys, P.W.; Tsai, T.Y.; Kelm, M.; Jung, C. Extended reality in cardiovascular care: A systematic review. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2025, 6, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jóźwik, S.; Cieślik, B.; Gajda, R.; Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. Evaluation of the Impact of Virtual Reality-Enhanced Cardiac Rehabilitation on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheluzzi, V.; Navarese, E.P.; Merella, P.; Talanas, G.; Viola, G.; Bandino, S.; Idini, C.; Burrai, F.; Casu, G. Clinical application of virtual reality in patients with cardiovascular disease: State of the art. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1356361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, G.F.; Ades, P.A.; Kligfield, P.; Arena, R.; Balady, G.J.; Bittner, V.A.; Coke, L.A.; Fleg, J.L.; Forman, D.E.; Gerber, T.C.; et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 128, 873–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Park, J.W.; Kim, Y.; Moon, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C.N.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, B.J. Biomechanical analysis of patients with mild Parkinson’s disease during indoor cycling training. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2025, 22, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Ross, R. Estimation of skeletal muscle mass by bioelectrical impedance analysis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; On, Y.K.; Kim, H.S.; Chae, I.H.; Sohn, D.W.; Oh, B.H.; Lee, M.M.; Park, Y.B.; Choi, Y.S.; Lee, Y.W. Development of Korean Activity Scale/Index (KASI). Korean Circ. J. 2000, 30, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, R.; de Charro, F. EQ-5D: A measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann. Med. 2001, 33, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Gong, H.S. Measurement and Interpretation of Handgrip Strength for Research on Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis. J. Bone Metab. 2020, 27, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroszczyk-McDonald, A.; Savage, P.D.; Ades, P.A. Handgrip strength in cardiac rehabilitation: Normative values, interaction with physical function, and response to training. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2007, 27, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittner, V. Six-minute walk test in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Cardiologia 1997, 42, 897–902. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.L.; Bonikowske, A.R.; Olson, T.P. Optimizing Outcomes in Cardiac Rehabilitation: The Importance of Exercise Intensity. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 734278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Zhu, J.; Shen, T.; Song, Y.; Tao, L.; Xu, S.; Zhao, W.; Gao, W. Comparison Between Treadmill and Bicycle Ergometer Exercises in Terms of Safety of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 864637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, C.; Raimundo, A.; Abreu, A.; Bravo, J. Exercise Intensity in Patients with Cardiovascular Diseases: Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbahi, A.; Canada, J.M.; Babu, A.S.; Severin, R.; Arena, R.; Ozemek, C. Exercise training in cardiac rehabilitation: Setting the right intensity for optimal benefit. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 70, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.M.; Pack, Q.R.; Aberegg, E.; Brewer, L.C.; Ford, Y.R.; Forman, D.E.; Gathright, E.C.; Khadanga, S.; Ozemek, C.; Thomas, R.J. Core Components of Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs: 2024 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 2024, 150, e328–e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.; Abreu, A.; Ambrosetti, M.; Cornelissen, V.; Gevaert, A.; Kemps, H.; Laukkanen, J.A.; Pedretti, R.; Simonenko, M.; Wilhelm, M.; et al. Exercise intensity assessment and prescription in cardiovascular rehabilitation and beyond: Why and how: A position statement from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 230–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, G.P.; Vleck, V.E.; Bentley, D.J. Physiological differences between cycling and running: Lessons from triathletes. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, L.A.; Stanley, C.J.; Norman, T.L.; Park, H.S.; Damiano, D.L. Comparison of elliptical training, stationary cycling, treadmill walking and overground walking. Electromyographic patterns. Gait Posture 2011, 33, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Sinha, S.; Kumari, A.; Dhanvijay, A.K.D.; Singh, S.K.; Mondal, H. Comparison of Cardiovascular Response to Lower Body and Whole Body Exercise Among Sedentary Young Adults. Cureus 2023, 15, e45880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cersosimo, A.; Longo Elia, R.; Condello, F.; Colombo, F.; Pierucci, N.; Arabia, G.; Matteucci, A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Vizzardi, E.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suebkinorn, O.; Ramos, J.S.; Grace, S.L.; Gebremichael, L.G.; Bulamu, N.B.; Pinero de Plaza, M.A.; Dafny, H.A.; Pearson, V.; Bulto, L.N.; Chen, R.T.; et al. Effectiveness of alternative exercises in cardiac rehabilitation for program completion and outcomes in women with or at high risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBI Evid. Synth. 2025, 23, 1041–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlach, S.; Mermier, C.; Kravitz, L.; Degnan, J.; Dalleck, L.; Zuhl, M. Comparison of Treadmill and Cycle Ergometer Exercise During Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloc, D.; Nowak, Z.; Nowak-Lis, A.; Gabryś, T.; Szmatlan-Gabrys, U.; Valach, P.; Pilis, A. Indoor cycling training in rehabilitation of patients after myocardial infarction. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 13, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, B.; Glasziou, P.; Hoffmann, T. The Contribution of Individual Exercise Training Components to Clinical Outcomes in Randomised Controlled Trials of Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression. Sports Med. Open 2017, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Fang, H.; Wang, X. Factors associated with participation in cardiac rehabilitation in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 2023, 46, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Under 60 | Over 60 | p-Value | |

| (N = 20) | (N = 11) | (N = 9) | ||

| Age (years) | 56.1 (±11.7) | 47.5 (±7.5) | 66.6 (±5.2) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 174.3 (±7.4) | 177.4 (±8.2) | 170.6 (±4.3) | 0.038 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.4 (±11.7) | 81.3 (±12.0) | 70.4 (±8.5) | 0.035 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.1 (±2.8) | 25.8 (±3.0) | 24.2 (±2.2) | 0.210 |

| Diagnosis (number) | ||||

| Angina | 7 (35%) | 3 (15%) | 4 (20%) | |

| NSTEMI | 2 (10%) | 2 (10%) | ||

| STEMI | 5 (25%) | 4 (20%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Heart failure | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Valvular heart disease | 2 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Aortic disease | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Infective endocarditis | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| SMI (kg/m2) | 8.3 (±0.6) | 8.5 (±0.5) | 8.0 (±0.6) | 0.099 |

| KASI | 66.2 (9.9) | 65.7 (9.6) | 66.9 (10.9) | 0.824 |

| EQ-5D | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 0.766 |

| Hand grip strength (kg) | 40.9 (±5.4) | 43.2 (±4.1) | 38.0 (±5.8) | 0.029 |

| 6 min walk test (m) | 561.2 (±67.4) | 557.7 (±62.7) | 565.3 (±76.4) | 0.809 |

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Under 60 | Over 60 | p-Value | |

| (N = 20) | (N = 11) | (N = 9) | ||

| Peak VO2 (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 28.4 (±5.6) | 31.8 (±4.7) | 24.1 (±3.1) | <0.001 |

| Peak VT (L/min) | 15.8 (±3.9) | 15.9 (±3.5) | 15.7 (±4.5) | 0.925 |

| Peak HR (bpm) | 151.9 (±20.3) | 163.6 (±16.2) | 137.6 (±15.4) | 0.002 |

| Rest HR (bpm) | 75.0 (18.3) | 77.0 (18.0) | 70.0 (16.0) | 0.295 |

| Peak predicted HR (%) | 92.1 (±9.2) | 94.5 (±8.9) | 89.1 (±9.3) | 0.207 |

| Peak METs | 8.1 (±1.6) | 9.1 (±1.3) | 6.9 (±0.9) | <0.001 |

| VE/VCO2 | 25.5 (±3.9) | 25.0 (±4.1) | 26.1 (±3.8) | 0.531 |

| Peak SBP (mmHg) | 185.5 (±29.8) | 193.6 (±28.7) | 175.4 (±29.5) | 0.181 |

| Peak DBP (mmHg) | 80.7 (±14.0) | 85.1 (±13.4) | 75.3 (±13.5) | 0.124 |

| Rest SBP (mmHg) | 128.5 (±16.7) | 125.8 (±16.1) | 131.7 (±17.8) | 0.451 |

| Rest DBP (mmHg) | 80.1 (±10.3) | 84.7 (±9.1) | 74.4 (±9.1) | 0.022 |

| Exercise duration (s) | 902.3 (±92.8) | 909.4 (±73.1) | 893.7 (±116.8) | 0.718 |

| Peak RER | 1.1 (±0.1) | 1.2 (±0.1) | 1.1 (±0.1) | 0.050 |

| Peak RPP (mmHg · bpm) | 25,451.4 (±6402.8) | 28,420.7 (±5699.4) | 21,822.2 (±5460.8) | 0.017 |

| Peak RPE | 14.6 (±1.1) | 14.8 (±1.1) | 14.2 (±1.0) | 0.295 |

| Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Under 60 | Over 60 | p-Value | |

| (N = 20) | (N = 11) | (N = 9) | ||

| Mean VO2 (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 19.8 (±5.7) | 19.6 (±5.0) | 20.0 (±6.7) | 0.897 |

| Mean HR (bpm) | 135.2 (±18.5) | 141.3 (±19.1) | 127.7 (±15.5) | 0.102 |

| Rest HR (bpm) | 85.6 (±13.7) | 87.5 (±12.9) | 83.2 (±15.1) | 0.507 |

| Mean Predicted HR (%) | 80.9 (±11.0) | 79.5 (±12.4) | 83.2 (±15.1) | 0.546 |

| Mean METs | 5.7 (±1.6) | 5.6 (±1.4) | 5.7 (±1.9) | 0.904 |

| Mean VE/VCO2 | 28.7 (±7.2) | 29.8 (±4.6) | 27.3 (±9.6) | 0.450 |

| Mean SBP (mmHg) | 174.2 (±25.1) | 171.2 (±26.4) | 177.8 (±24.3) | 0.572 |

| Mean DBP (mmHg) | 82.2 (±11.2) | 80.5 (±10.8) | 84.2 (±12.0) | 0.469 |

| Rest SBP (mmHg) | 119.2 (±14.6) | 119.0 (±15.1) | 119.3 (±14.8) | 0.961 |

| Rest DBP (mmHg) | 77.6 (±11.0) | 79.8 (±10.9) | 74.8 (±11.2) | 0.322 |

| Exercise duration | 601.0 (1.0) | 601.0 (1.0) | 601.0 (1.0) | 0.656 |

| Mean RER | 1.0 (±0.1) | 1.0 (±0.1) | 0.9 (±0.1) | 0.485 |

| Mean RPP (mmHg · bpm) | 22,532.5 (±4496.4) | 23,083.4 (±5529.6) | 21,859.1 (±2978.2) | 0.559 |

| Mean RPE | 13.2 (±1.7) | 12.7 (±1.6) | 13.8 (±1.9) | 0.331 |

| Treadmill | Cycling Device | Cycling/ Treadmill | ACSM-Recommended Exercise Intensity 1 | EAPC/ESC-Recommended Exercise Intensity 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO2 (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 28.4 ± 5.6 | 19.8 ± 5.7 | 69.7% | Moderate (46–63%) Vigorous (64–90%) | Moderate (40–69%) Vigorous (70–85%) |

| HR (bpm) | 152.8 ± 19.8 | 134.9 ± 18.4 | 88.3% | Moderate (64–76%) Vigorous (77–95%) | Moderate (55–74%) Vigorous (75–90%) |

| METs | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 68.3% | Moderate (46–63%) Vigorous (64–90%) | Moderate (46–63%) Vigorous (64–90%) |

| RPE | 14.6 ± 1.1 | 13.2 ± 1.7 | Moderate 12–13 Vigorous 14–17 | Moderate 12–13 Vigorous 14–16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.T.; Kim, B.R.; Pyun, S.B.; Kim, Y.M.; Son, H.S.; Jung, J.S.; Kim, H.J. Feasibility and Safety of an Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Pilot Validation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8947. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248947

Lee JT, Kim BR, Pyun SB, Kim YM, Son HS, Jung JS, Kim HJ. Feasibility and Safety of an Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Pilot Validation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8947. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248947

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jin Taek, Bo Ryun Kim, Sung Bom Pyun, Young Mo Kim, Ho Sung Son, Jae Seung Jung, and Hee Jung Kim. 2025. "Feasibility and Safety of an Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Pilot Validation Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8947. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248947

APA StyleLee, J. T., Kim, B. R., Pyun, S. B., Kim, Y. M., Son, H. S., Jung, J. S., & Kim, H. J. (2025). Feasibility and Safety of an Outdoor-Simulated Interactive Indoor Cycling Device for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Pilot Validation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8947. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248947