Two-Year Clinical Outcomes of Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia Versus Claudication After Femoropopliteal Endovascular Therapy: An Analysis from K-VIS ELLA Registry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

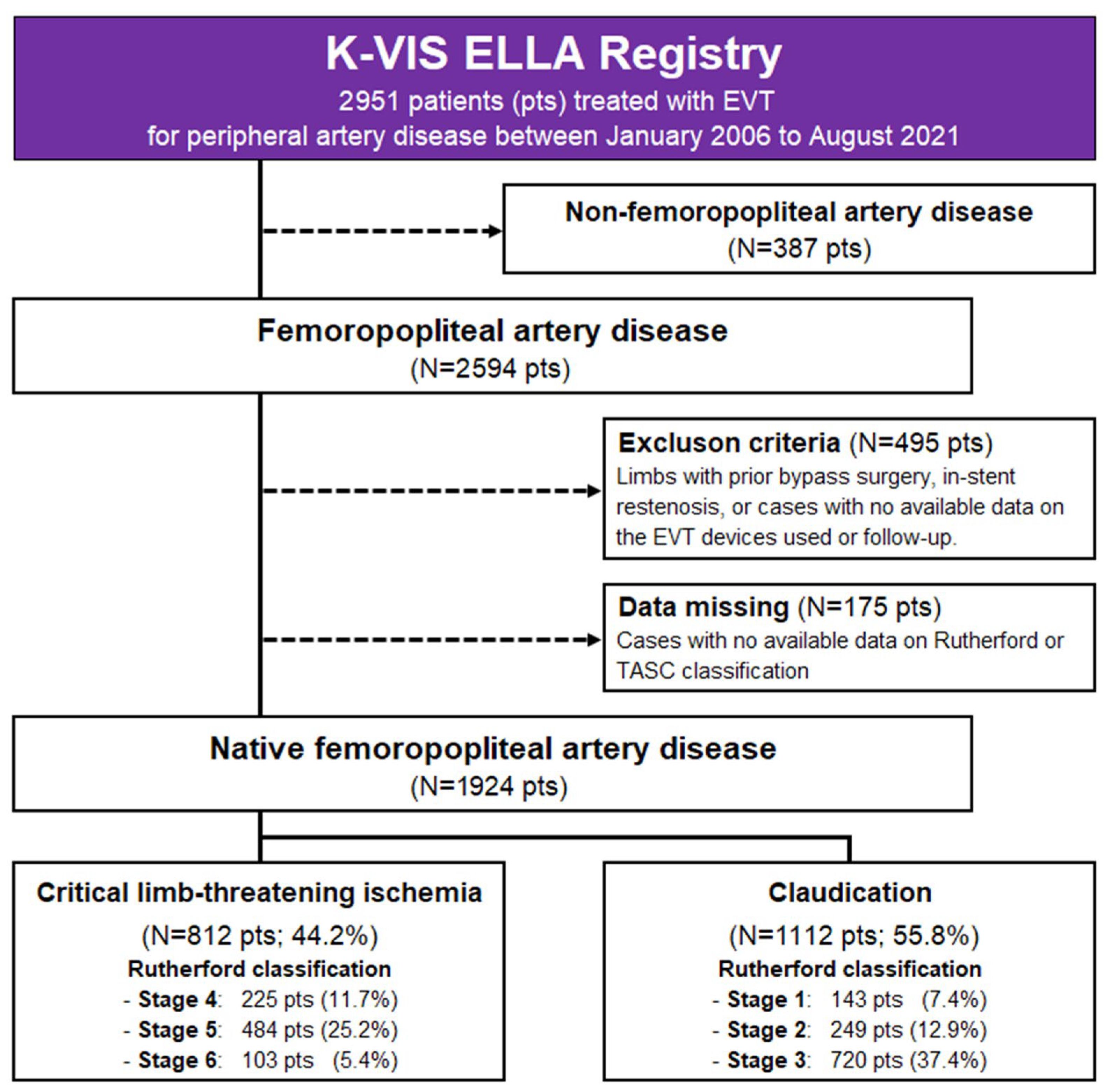

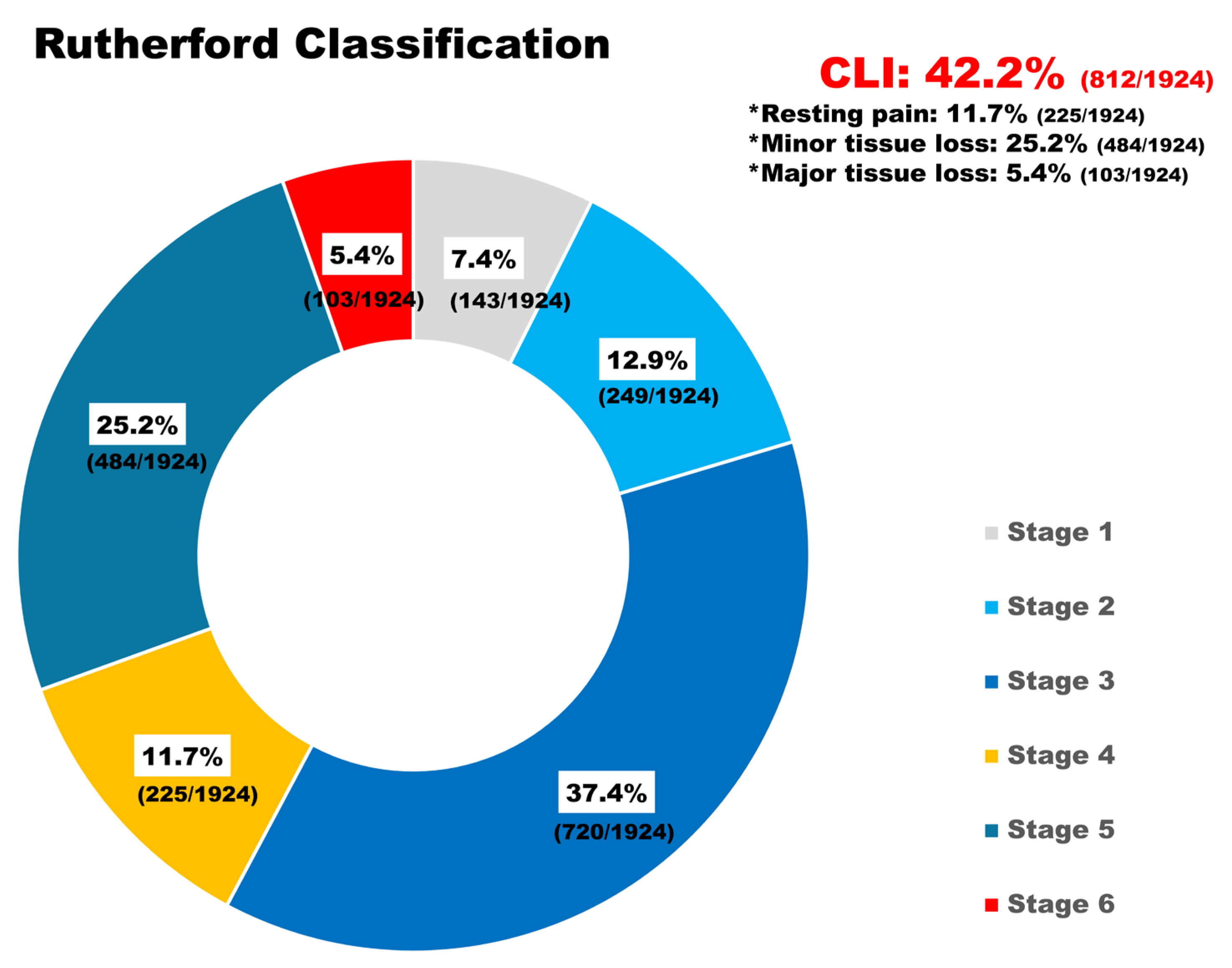

2.2. Population

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Definitions and Study Endpoints

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Outcomes

3.3. Subgroup Analysis: Treatment Strategy and Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLTI | critical limb-threatening ischemia |

| DCB | drug-coated balloon |

| DES | drug-eluting stent |

| FPA | femoropopliteal artery |

| IC | intermittent claudication |

| IPTW | inverse probability weighting |

| POBA | plain old balloon angioplasty |

| PTA | percutaneous transluminal angioplasty |

References

- Shu, J.; Santulli, G. Update on peripheral artery disease: Epidemiology and evidence-based facts. Atherosclerosis 2018, 275, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.-G.; Ahn, C.-M.; Min, P.-K.; Lee, J.-H.; Yoon, C.-H.; Yu, C.W.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S.-R.; Choi, S.H.; Koh, Y.S.; et al. Baseline Characteristics of a Retrospective Patient Cohort in the Korean Vascular Intervention Society Endovascular Therapy in Lower Limb Artery Diseases (K-VIS ELLA) Registry. Korean Circ. J. 2017, 47, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, H.H.; Ko, Y.G.; Ahn, C.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, B.K.; Hong, M.K.; Chang Kim, H.; Yu, C.W.; et al. Device Effectiveness for Femoropopliteal Artery Disease Treatment: An Analysis of K-VIS ELLA Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2023, 16, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varu, V.N.; Hogg, M.E.; Kibbe, M.R. Critical limb ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 51, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzolai, L.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Lanzi, S.; Boc, V.; Bossone, E.; Brodmann, M.; Bura-Riviere, A.; De Backer, J.; Deglise, S.; Della Corte, A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3538–3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tepe, G.; Laird, J.; Schneider, P.; Brodmann, M.; Krishnan, P.; Micari, A.; Metzger, C.; Scheinert, D.; Zeller, T.; Cohen, D.J.; et al. Drug-coated balloon versus standard percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for the treatment of superficial femoral and popliteal peripheral artery disease: 12-month results from the IN.PACT SFA randomized trial. Circulation 2015, 131, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfield, K.; Jaff, M.R.; White, C.J.; Rocha-Singh, K.; Mena-Hurtado, C.; Metzger, D.C.; Brodmann, M.; Pilger, E.; Zeller, T.; Krishnan, P.; et al. Trial of a Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon for Femoropopliteal Artery Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liistro, F.; Angioli, P.; Porto, I.; Ducci, K.; Falsini, G.; Ventoruzzo, G.; Ricci, L.; Scatena, A.; Grotti, S.; Bolognese, L. Drug-Eluting Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Complex Femoropopliteal Arterial Lesions: The DRASTICO Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausback, Y.; Wittig, T.; Schmidt, A.; Zeller, T.; Bosiers, M.; Peeters, P.; Brucks, S.; Lottes, A.; Scheinert, D.; Steiner, S. Drug-Eluting Stent Versus Drug-Coated Balloon Revascularization in Patients with Femoropopliteal Arterial Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouëffic, Y.; Torsello, G.; Zeller, T.; Esposito, G.; Vermassen, F.; Hausegger, K.A.; Tepe, G.; Thieme, M.; Gschwandtner, M.; Kahlberg, A.; et al. Efficacy of a Drug-Eluting Stent Versus Bare Metal Stents for Symptomatic Femoropopliteal Peripheral Artery Disease: Primary Results of the EMINENT Randomized Trial. Circulation 2022, 146, 1564–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabellino, M.; Zander, T.; Baldi, S.; Nielsen, L.G.; Aragon-Sanchez, F.J.; Zerolo, I.; Llorens, R.; Maynar, M. Clinical follow-up in endovascular treatment for TASC C-D lesions in femoro-popliteal segment. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 73, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamedali, A.; Kiwan, G.; Kim, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuo, H.; Tonnessen, B.; Dardik, A.; Chaar, C.I.O. Reinterventions in Patients with Claudication and Chronic Limb Threatening Ischemia. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 79, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Whealon, M.D.; Kabutey, N.K.; Kuo, I.J.; Sgroi, M.D.; Fujitani, R.M. Outcomes of open and endovascular lower extremity revascularization in active smokers with advanced peripheral arterial disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 1680–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehler, M.R.; Duval, S.; Diao, L.; Annex, B.H.; Hiatt, W.R.; Rogers, K.; Zakharyan, A.; Hirsch, A.T. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia in an insured national population. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 686–695.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, A.T.; Allison, M.A.; Gomes, A.S.; Corriere, M.A.; Duval, S.; Ershow, A.G.; Hiatt, W.R.; Karas, R.H.; Lovell, M.B.; McDermott, M.M.; et al. A call to action: Women and peripheral artery disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012, 125, 1449–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, G.W.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Yang, Y.S.; Ko, Y.G.; Choi, M. Incidence and Prevalence of Peripheral Arterial Disease in South Korea: Retrospective Analysis of National Claims Data. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e34908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Park, Y.J.; Min, S.-I.; Kim, S.Y.; Ha, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.-S.; Yoon, B.-W.; Min, S.-K. High Prevalence of Peripheral Arterial Disease in Korean Patients with Coronary or Cerebrovascular Disease. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2012, 27, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnen, M.M.P.J.; van Wijck, I.; Brodmann, M.; Micari, A.; Torsello, G.; Rha, S.-W.; Menk, J.; Zeller, T.; On behalf of the IN.PACT Global Study Investigators. Five-Year Outcomes after Paclitaxel Drug-Coated Balloon Treatment of Femoropopliteal Lesions in Diabetic and Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia Cohorts: IN.PACT Global Study Post Hoc Analysis. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 46, 1329–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawarada, O.; Zen, K.; Hozawa, K.; Obara, H.; Matsubara, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Doijiri, T.; Tamai, N.; Ito, S.; Higashimori, A.; et al. Characteristics, Antithrombotic Patterns, and Prognostic Outcomes in Claudication and Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia Undergoing Endovascular Therapy. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2022, 31, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodney, P.P.; Holman, K.; Henke, P.K.; Travis, L.L.; Dimick, J.B.; Stukel, T.A.; Fisher, E.S.; Birkmeyer, J.D. Regional intensity of vascular care and lower extremity amputation rates. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 1471–1480.e3, discussion 1479–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, M.D.; Ansel, G.M.; Jaff, M.R.; Ohki, T.; Saxon, R.R.; Smouse, H.B.; Snyder, S.A.; O’Leary, E.E.; Tepe, G.; Scheinert, D.; et al. Sustained safety and effectiveness of paclitaxel-eluting stents for femoropopliteal lesions: 2-year follow-up from the Zilver PTX randomized and single-arm clinical studies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 2417–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, M.; Von Bilderling, P.; Paetzel, C.; Karnabatidis, D.; Perez Delgado, J.; Lichtenberg, M. The 24-Month Results of the Lutonix Global SFA Registry: Worldwide Experience with Lutonix Drug-Coated Balloon. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Piorkowski, M.; Görner, H.; Steiner, S.; Bausback, Y.; Scheinert, S.; Banning-Eichenseer, U.; Staab, H.; Branzan, D.; Varcoe, R.L.; et al. Drug-Coated Balloons for Complex Femoropopliteal Lesions: 2-Year Results of a Real-World Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodmann, M.; Keirse, K.; Scheinert, D.; Spak, L.; Jaff, M.R.; Schmahl, R.; Li, P.; Zeller, T. Drug-Coated Balloon Treatment for Femoropopliteal Artery Disease: The IN.PACT Global Study De Novo In-Stent Restenosis Imaging Cohort. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 2113–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, K.; Ullery, B.W.; Kret, M.R.; Lee, J.T. Real-World Performance of Paclitaxel Drug-Eluting Bare Metal Stenting (Zilver PTX) for the Treatment of Femoropopliteal Occlusive Disease. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 38, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, W.A.; Keirse, K.; Soga, Y.; Benko, A.; Babaev, A.; Yokoi, Y.; Schroeder, H.; Prem, J.T.; Holden, A.; Popma, J.; et al. A polymer-coated, paclitaxel-eluting stent (Eluvia) versus a polymer-free, paclitaxel-coated stent (Zilver PTX) for endovascular femoropopliteal intervention (IMPERIAL): A randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Crude Population | IPTW Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Mean ± SD or n (%) | CLTI (n = 812) | Claudication (n = 1112) | SMD | CLTI (n = 1915) | Claudication (n = 2010) | SMD |

| Sex, male | 618 (76.1) | 953 (85.7) | 0.011 | 1565 (81.7) | 1642 (81.6) | 0.000 |

| Age, years | 70.3 ± 10.7 | 69.0 ± 10.3 | −0.013 | 69.1 ± 11.1 | 70.4 ± 10.9 | 0.011 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.6 ± 3.5 | 23.6 ± 3.2 | 0.029 | 23.3 ± 3.7 | 23.1 ± 3.2 | −0.007 |

| Patient risks | ||||||

| Hypertension | 601 (74.0) | 855 (76.8) | 0.003 | 1441 (75.2) | 1464 (72.8) | −0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 581 (71.5) | 672 (60.4) | −0.014 | 1266 (66.1) | 1302 (64.7) | −0.002 |

| Dyslipidemia | 422 (51.9) | 689 (61.9) | 0.013 | 1086 (56.7) | 1095 (54.4) | −0.003 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 288 (35.4) | 210 (18.8) | −0.032 | 507 (26.4) | 538 (26.7) | 0.001 |

| eGFR-MDRD | 60 ± 39 | 69 ± 33 | 0.026 | 64 ± 36 | 65 ± 37 | 0.002 |

| ESRD | 188 (23.1) | 101 (9) | −0.035 | 295 (15.4) | 272 (13.5) | −0.005 |

| COPD | 32 (3.9) | 41 (3.6) | −0.001 | 86 (4.4) | 81 (4.0) | −0.002 |

| Congestive heart failure | 54 (6.6) | 37 (3.3) | −0.015 | 90 (4.6) | 84 (4.1) | −0.002 |

| Coronary artery disease | 370 (45.5) | 606 (54.4) | 0.013 | 973 (50.8) | 975 (48.5) | −0.003 |

| Prior MI | 60 (7.3) | 92 (8.2) | 0.003 | 146 (7.6) | 154 (7.6) | 0.000 |

| Prior PCI | 198 (24.3) | 361 (32.4) | 0.015 | 580 (30.2) | 573 (28.5) | −0.003 |

| Prior CABG | 72 (8.8) | 97 (8.7) | 0.000 | 154 (8.0) | 156 (7.7) | −0.001 |

| Stroke | 166 (20.4) | 177 (15.9) | −0.011 | 346 (18.0) | 336 (16.7) | −0.003 |

| Prior PTA | 287 (35.3) | 351 (31.5) | −0.007 | 646 (33.7) | 650 (32.3) | −0.002 |

| Smoking | 195 (24.0) | 331 (29.7) | 0.011 | 559 (29.1) | 517 (25.7) | −0.007 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||||

| Glucose levels, mg/dL | 152 ± 82 | 145 ± 74 | −0.010 | 148 ± 77 | 150 ± 81 | 0.003 |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | 7.7 ± 5.7 | 7.5 ± 5.7 | −0.004 | 7.5 ± 4.3 | 7.4 ± 4.6 | −0.002 |

| Creatinine levels, mg/dL | 2.26 ± 2.53 | 1.61 ± 2.05 | −0.028 | 1.93 ± 2.25 | 1.88 ± 2.28 | −0.002 |

| Hemoglobin levels, mg/dL | 11.4 ± 2.2 | 12.6 ± 3.5 | 0.041 | 12.1 ± 2.4 | 11.9 ± 3.1 | −0.006 |

| Total cholesterol levels, mg/dL | 141 ± 40 | 143 ± 39 | 0.006 | 145 ± 41 | 143 ± 39 | −0.006 |

| Triglyceride levels, mg/dL | 121 ± 76 | 139 ± 95 | 0.021 | 144 ± 129 | 130 ± 85 | −0.012 |

| HDL levels, mg/dL | 37 ± 11 | 41 ± 11 | 0.031 | 39 ± 12 | 39 ± 11 | −0.003 |

| LDL levels, mg/dL | 81 ± 32 | 79 ± 33 | −0.005 | 81 ± 32 | 80 ± 33 | −0.004 |

| Crude Population | IPTW Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Mean ± SD or n (%) | CLTI (n = 812) | Claudication (n = 1112) | SMD | CLTI (n = 1915) | Claudication (n = 2010) | SMD |

| Angiographic and procedural characteristics | ||||||

| Limb side, Right | 395 (48.6) | 543 (48.8) | 0.000 | 956 (49.9) | 983 (48.9) | −0.001 |

| Procedural approach | ||||||

| Ipsilateral | 311 (38.3) | 260 (23.3) | −0.027 | 575 (30.0) | 589 (29.3) | −0.001 |

| Contralateral | 525 (64.6) | 888 (79.8) | 0.018 | 1410 (73.6) | 1475 (73.3) | 0.000 |

| Lesion location | ||||||

| Distal aorta | 108 (13.3) | 162 (14.5) | 0.003 | 271 (14.1) | 323 (16.0) | 0.005 |

| Common iliac artery | 108 (13.3) | 167 (15.0) | 0.005 | 271 (14.1) | 328 (16.3) | 0.006 |

| Common femoral artery | 25 (3.0) | 45 (4.0) | 0.005 | 62 (3.2) | 61 (3.0) | −0.001 |

| Superficial femoral artery | 812 (100.0) | 1112 (100.0) | - | 1915 (100.0) | 2010 (100.0) | - |

| Infra-popliteal artery | 395 (48.6) | 205 (18.4) | −0.052 | 594 (31.0) | 670 (33.3) | 0.004 |

| Anterior tibial artery | 227 (27.9) | 74 (6.6) | −0.051 | 331 (17.2) | 342 (17.0) | −0.001 |

| Posterior tibial artery | 157 (19.3) | 44 (3.9) | −0.045 | 203 (10.6) | 308 (15.3) | 0.013 |

| Peroneal artery | 110 (13.5) | 39 (3.5) | −0.034 | 148 (7.7) | 168 (8.3) | 0.002 |

| Total occlusion lesion | 394 (48.5) | 541 (48.6) | 0.000 | 957 (49.9) | 1000 (49.7) | 0.000 |

| Calcified lesion | 493 (60.7) | 584 (52.5) | −0.011 | 1020 (53.2) | 1124 (55.9) | 0.004 |

| Moderate/Severe calcification | 260 (32.0) | 312 (28.1) | −0.087 | 547 (28.6) | 669 (33.3) | 0.102 |

| TASC-II (A/B) | 329 (40.5) | 497 (44.7) | 0.085 | 776 (40.5) | 824 (41.0) | 0.010 |

| TASC-II (C/D) | 483 (59.5) | 615 (55.3) | −0.085 | 1139 (59.5) | 1186 (59.0) | −0.010 |

| Lesion length ≥ 150 mm | 461 (56.8) | 532 (48.1) | −0.176 | 1076 (56.3) | 1112 (55.6) | −0.014 |

| Distal runoff vessels | 2.39 (0.85) | 2.86 (0.45) | 0.069 | 2.59 (0.80) | 2.64 (0.70) | 0.007 |

| lesion stenosis, % | 89.7 ± 13.1 | 91.1 ± 11.6 | 0.011 | 90.6 ± 12.4 | 90.7 ± 12.3 | 0.001 |

| Lesion diameter, mm (max) | 6.08 ± 0.9 | 6.24 ± 0.8 | 0.019 | 6.14 ± 0.87 | 6.18 ± 0.79 | 0.004 |

| Total lesion length, mm | 175 ± 105 | 163 ± 110 | −0.011 | 173 ± 104 | 173 ± 106 | 0.000 |

| Sub-intimal approach | 158 (19.4) | 160 (14.3) | −0.012 | 322 (16.8) | 306 (15.2) | −0.004 |

| Atherectomy | 86 (10.5) | 130 (11.6) | 0.003 | 224 (11.6) | 288 (14.3) | 0.007 |

| DAART | 71 (8.7) | 120 (10.7) | 0.007 | 194 (10.1) | 249 (12.3) | 0.007 |

| Lesion treatment | ||||||

| POBA only | 231 (28.4) | 215 (19.3) | −0.019 | 448 (23.3) | 451 (22.4) | −0.002 |

| BMS only | 262 (32.2) | 382 (34.3) | 0.004 | 618 (32.2) | 615 (30.5) | −0.003 |

| DCB only | 203 (25.0) | 304 (27.3) | 0.005 | 508 (26.5) | 611 (30.3) | 0.007 |

| DCB + BMS | 31 (3.8) | 71 (6.3) | 0.011 | 115 (6.0) | 99 (4.9) | −0.005 |

| DES only | 61 (7.5) | 115 (10.3) | 0.009 | 179 (9.3) | 172 (8.5) | −0.003 |

| Type of DCB | ||||||

| IN.PACT Admiral | 161 (73.9) | 261 (74.6) | 0.089 | 440 (68.8) | 472 (73.8) | 0.108 |

| Lutonix | 41 (18.8) | 38 (10.9) | −0.081 | 108 (16.9) | 97 (15.2) | −0.045 |

| Ranger | 12 (5.5) | 42 (12.0) | 0.139 | 92 (14.4) | 71 (11.1) | −0.103 |

| Crude Population | IPTW Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Mean ± SD or n (%) | CLTI (n = 812) | Claudication (n = 1112) | p-Value | CLTI (n = 1915) | Claudication (n = 2010) | p-Value |

| Procedural outcomes | ||||||

| Residual stenosis, >30% | 17 (2.0) | 23 (2.0) | 0.969 | 27 (1.4) | 33 (1.6) | 0.554 |

| Technical success | 785 (96.6) | 1075 (96.6) | 0.998 | 1869 (97.5) | 1958 (97.4) | 0.710 |

| Ankle brachial index (ABI) | ||||||

| ABI before PTA | 0.59 ± 0.26 | 0.62 ± 0.18 | 0.019 | 0.59 ± 0.23 | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 0.155 |

| ABI after PTA | 0.87 ± 0.20 | 0.89 ± 0.17 | 0.028 | 0.87 ± 0.20 | 0.90 ± 0.16 | 0.001 |

| Procedural complications | ||||||

| Any complications | 51 (6.2) | 31 (2.7) | <0.001 | 101 (5.2) | 62 (3.0) | 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 33 (4.0) | 20 (1.7) | 0.003 | 60 (3.1) | 41 (2.0) | 0.030 |

| Vascular rupture | 15 (1.8) | 8 (0.7) | 0.025 | 33 (1.7) | 15 (0.7) | 0.005 |

| Distal embolization | 6 (0.7) | 3 (0.2) | 0.180 | 13 (0.6) | 5 (0.2) | 0.046 |

| Discharge medications | ||||||

| Aspirin | 612 (75.3) | 901 (81.0) | 0.003 | 1517 (79.2) | 1549 (77.0) | 0.103 |

| P2Y12 inhibitors | 616 (75.8) | 964 (86.6) | <0.001 | 1539 (80.3) | 1718 (85.4) | <0.001 |

| Cilostazol | 212 (26.1) | 365 (32.8) | 0.001 | 477 (24.9) | 612 (30.4) | <0.001 |

| Beraprost | 95 (11.6) | 62 (5.5) | <0.001 | 170 (8.8) | 124 (6.1) | 0.001 |

| Triflusal | 2 (0.2) | 16 (1.4) | 0.007 | 8 (0.4) | 27 (1.3) | 0.002 |

| Sarpogrelate | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.2) | 0.702 | 6 (0.3) | 4 (0.1) | 0.539 |

| Anticoagulants | 81 (9.9) | 97 (8.7) | 0.349 | 209 (10.9) | 159 (7.9) | 0.001 |

| Warfarin | 65 (8.0) | 73 (6.5) | 0.227 | 155 (8.0) | 115 (5.7) | 0.003 |

| NOAC | 16 (1.9) | 24 (2.1) | 0.776 | 54 (2.8) | 44 (2.1) | 0.206 |

| RAS inhibitors | 332 (40.8) | 569 (51.1) | <0.001 | 832 (43.4) | 898 (44.6) | 0.438 |

| ACE inhibitors | 71 (8.7) | 121 (10.8) | 0.122 | 190 (9.9) | 195 (9.7) | 0.817 |

| ARBs | 267 (32.8) | 456 (41) | <0.001 | 657 (34.3) | 713 (35.4) | 0.444 |

| β-blockers | 276 (33.9) | 393 (35.3) | 0.539 | 682 (35.6) | 723 (35.9) | 0.816 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 275 (33.8) | 404 (36.3) | 0.264 | 663 (34.6) | 730 (36.3) | 0.272 |

| Diuretics | 157 (19.3) | 182 (16.3) | 0.091 | 358 (18.6) | 349 (17.3) | 0.278 |

| Statins | 536 (66.0) | 869 (78.1) | <0.001 | 1399 (73.0) | 1414 (70.3) | 0.060 |

| Outcomes Mean ± SD or n (%) | CLTI | Claudication | p-Value | HR [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude population | (n = 812) | (n = 1112) | |||

| Primary endpoint | 174 (21.4) | 149 (13.3) | <0.001 | 1.762 [1.385–2.242] | <0.001 |

| Any amputation | 71 (8.7) | 7 (0.6) | <0.001 | 15.12 [6.919–33.06] | <0.001 |

| Clinically driven TER | 96 (11.8) | 116 (10.4) | 0.336 | 1.151 [0.864–1.533] | 0.339 |

| Secondary endpoint | 471 (58.0) | 496 (44.6) | <0.001 | 1.715 [1.428–2.059] | <0.001 |

| Death | 107 (13.1) | 40 (3.5) | <0.001 | 4.067 [2.794–5.920] | <0.001 |

| Cardiac death | 47 (5.7) | 16 (1.4) | <0.001 | 4.208 [2.368–7.477] | <0.001 |

| Non-cardiac death | 60 (7.3) | 24 (2.1) | <0.001 | 3.617 [2.232–5.859] | <0.001 |

| Major amputation | 20 (2.4) | 2 (0.1) | <0.001 | 14.01 [3.266–60.13] | <0.001 |

| Repeated PTA | 107 (13.1) | 127 (11.4) | 0.244 | 1.177 [0.894–1.549] | 0.259 |

| Non-TER | 12 (1.4) | 11 (0.9) | 0.330 | 1.501 [0.659–3.419] | 0.397 |

| MALEs | 161 (19.8) | 132 (11.8) | <0.001 | 1.836 [1.429–2.358] | <0.001 |

| Symptom aggravation | 453 (55.7) | 477 (42.8) | <0.001 | 1.679 [1.399–2.016] | <0.001 |

| Clinical patency | 354 (43.5) | 628 (56.4) | <0.001 | 1.678 [1.398–2.014] | <0.001 |

| IPTW population | (n = 1915) | (n = 2010) | |||

| Primary endpoint | 337 (17.5) | 281 (13.9) | 0.002 | 1.314 [1.105–1.561] | 0.002 |

| Any amputation | 120 (6.2) | 17 (0.8) | <0.001 | 7.837 [4.697–13.076] | <0.001 |

| Clinically driven TER | 197 (10.2) | 211 (10.4) | 0.829 | 0.977 [0.796–1.200] | 0.834 |

| Secondary endpoint | 994 (51.9) | 907 (45.1) | <0.001 | 1.312 [1.157–1.488] | <0.001 |

| Death | 184 (9.6) | 85 (4.2) | <0.001 | 2.407 [1.846–3.138] | <0.001 |

| Cardiac death | 75 (3.9) | 33 (1.6) | <0.001 | 2.441 [1.613–3.695] | <0.001 |

| Non-cardiac death | 109 (5.6) | 51 (2.5) | <0.001 | 2.318 [1.652–3.252] | <0.001 |

| Major amputation | 34 (1.7) | 8 (0.3) | <0.001 | 4.523 [2.088–9.796] | <0.001 |

| Repeated PTA | 221 (11.5) | 229 (11.3) | 0.885 | 1.014 [0.833–1.234] | 0.920 |

| Non-TER | 26 (1.3) | 18 (0.8) | 0.169 | 1.523 [0.832–2.787] | 0.176 |

| MALEs | 318 (16.6) | 243 (12.0) | <0.001 | 1.447 [1.209–1.733] | <0.001 |

| Symptom aggravation | 956 (49.9) | 877 (43.6) | <0.001 | 1.287 [1.135–1.460] | <0.001 |

| Clinical patency | 944 (49.2) | 1120 (55.7) | <0.001 | 1.294 [1.141–1.467] | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.; Sinurat, M.R.M.P.; Rha, S.-W.; Choi, B.G.; Choi, S.Y.; Choi, C.U.; Ko, Y.-G.; Choi, D.; Lee, J.-H.; Yoon, C.-H.; et al. Two-Year Clinical Outcomes of Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia Versus Claudication After Femoropopliteal Endovascular Therapy: An Analysis from K-VIS ELLA Registry. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248919

Park S, Sinurat MRMP, Rha S-W, Choi BG, Choi SY, Choi CU, Ko Y-G, Choi D, Lee J-H, Yoon C-H, et al. Two-Year Clinical Outcomes of Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia Versus Claudication After Femoropopliteal Endovascular Therapy: An Analysis from K-VIS ELLA Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248919

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Soohyung, Markz R. M. P. Sinurat, Seung-Woon Rha, Byoung Geol Choi, Se Yeon Choi, Cheol Ung Choi, Young-Guk Ko, Donghoon Choi, Jae-Hwan Lee, Chang-Hwan Yoon, and et al. 2025. "Two-Year Clinical Outcomes of Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia Versus Claudication After Femoropopliteal Endovascular Therapy: An Analysis from K-VIS ELLA Registry" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248919

APA StylePark, S., Sinurat, M. R. M. P., Rha, S.-W., Choi, B. G., Choi, S. Y., Choi, C. U., Ko, Y.-G., Choi, D., Lee, J.-H., Yoon, C.-H., Chae, I.-H., Yu, C. W., Lee, S. W., Choi, S. H., Min, P.-K., Park, C. G., & on behalf of the K-VIS (Korean Vascular Intervention Society) Investigators. (2025). Two-Year Clinical Outcomes of Critical Limb-Threatening Ischemia Versus Claudication After Femoropopliteal Endovascular Therapy: An Analysis from K-VIS ELLA Registry. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8919. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248919