Relationship Between Maxillary Transverse Deficiency and Respiratory Problems: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Devices over the Past Decade

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration and Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Screening and Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Quality Assessment

2.8. Certainty of Evidence Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Article Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Airway Morphology

3.4. Respiratory Function and Breathing Outcomes

3.4.1. Polysomnographic and Respiratory Function Outcomes

3.4.2. Nasal Airway Patency

3.4.3. Subjective and Clinical Breathing Improvements

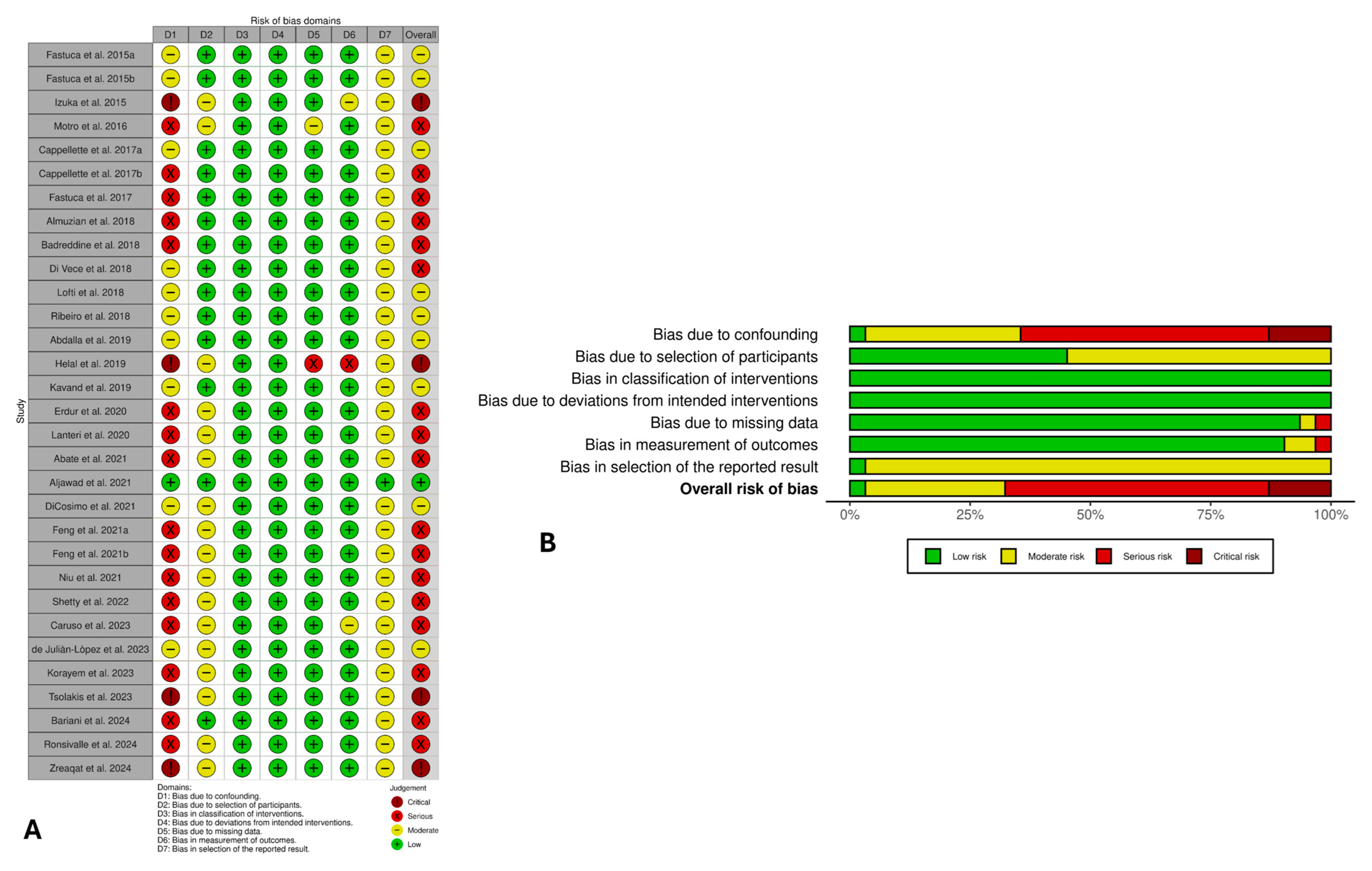

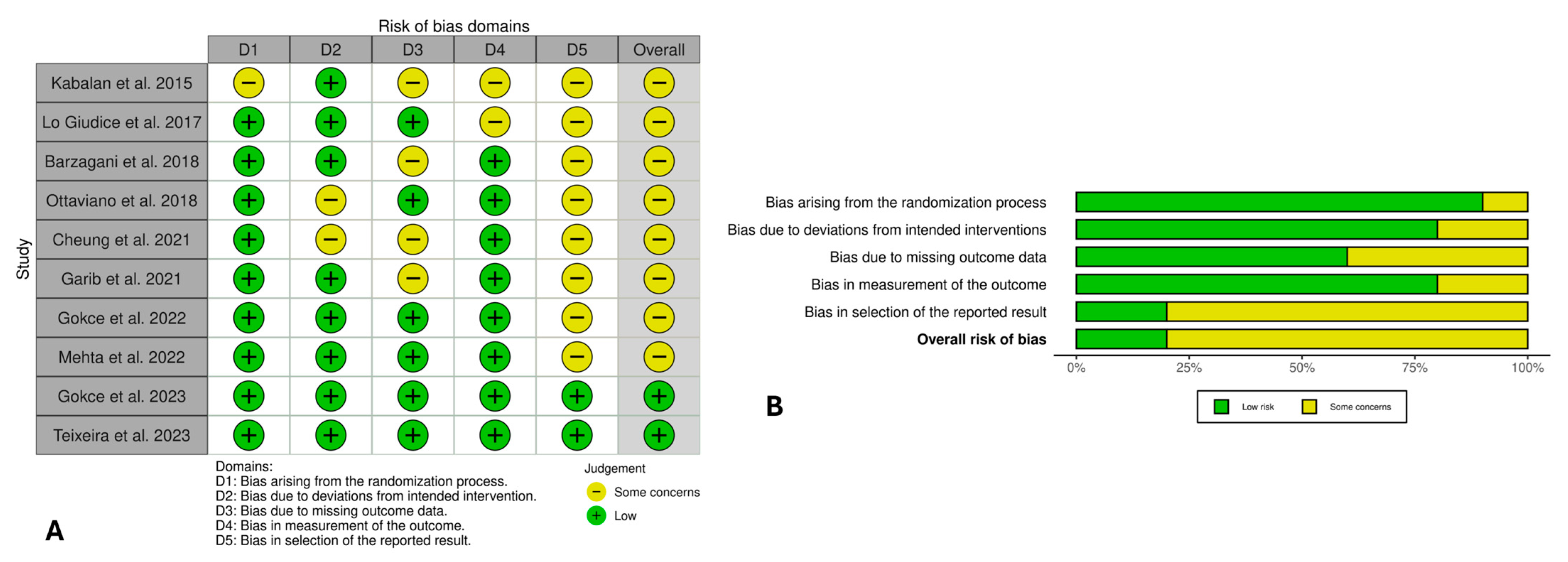

3.5. Risk of Bias Evaluation

3.6. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Z.; Zheng, L.; Huang, X.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Hu, Y. Effects of Mouth Breathing on Facial Skeletal Development in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.-A.; Kim, S.-J.; Yoon, A. Craniofacial Anatomical Determinants of Pediatric Sleep-Disordered Breathing: A Comprehensive Review. J. Prosthodont. 2025, 34, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, A.D.; Laforgia, A.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Latini, G.; Pezzolla, C.; Nardelli, P.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Malcangi, G.; Dipalma, G. Rapid Palate Expansion’s Impact on Nasal Breathing: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 190, 112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, K.; Ferrari-Piloni, C.; Barros, L.A.N.; Avelino, M.A.G.; Helena Soares Cevidanes, L.; Ruellas, A.C.d.O.; Valladares-Neto, J.; Silva, M.A.G. Three-Dimensional Assessment of Craniofacial Asymmetry in Children with Transverse Maxillary Deficiency after Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Prospective Study. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 23, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tang, Z.; Shan, Z.; Leung, Y.Y. Maxillary Deficiency: Treatments and Applications for Adolescents. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, G.; Saccucci, M.; Ierardo, G.; Luzzi, V.; Occasi, F.; Zicari, A.M.; Duse, M.; Polimeni, A. Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Upper Airway Morphology: A Systematic Review on the Role of Cone Beam Computed Tomography. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 5460429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, A.; Abdelwahab, M.; Bockow, R.; Vakili, A.; Lovell, K.; Chang, I.; Ganguly, R.; Liu, S.Y.-C.; Kushida, C.; Hong, C. Impact of Rapid Palatal Expansion on the Size of Adenoids and Tonsils in Children. Sleep Med. 2022, 92, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoloni, V.; Giuntini, V.; Lione, R.; Nieri, M.; Barone, V.; Merlo, M.M.; Mazza, F.; Passaleva, S.; Cozza, P.; Franchi, L. Comparison of the Dento-Skeletal Effects Produced by Leaf Expander versus Rapid Maxillary Expander in Prepubertal Patients: A Two-Center Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2021, 44, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Kalaskar, R.; Kalaskar, A. Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Upper Airway Volume: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Role of Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Mouth Breathing. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, B.; Hegde, K.S.; Bhat, S.S.; Umar, D.; Baroudi, K. Influence of Mouth Breathing on the Dentofacial Growth of Children: A Cephalometric Study. J. Int. Oral Health JIOH 2014, 6, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Feștilă, D.; Ciobotaru, C.D.; Suciu, T.; Olteanu, C.D.; Ghergie, M. Oral Breathing Effects on Malocclusions and Mandibular Posture: Complex Consequences on Dentofacial Development in Pediatric Orthodontics. Children 2025, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgalas, C. The Role of the Nose in Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: An Update. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2011, 268, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.I.; Kacker, A. Nasal Obstruction Considerations in Sleep Apnea. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 51, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, R. Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Diagnostic Challenges and Management Strategies. Cureus 2024, 16, e75347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-S.; Chen, I.-C.; Lin, P.-Y.; Chuang, L.-C. Craniofacial, Dental Arch Morphology, and Characteristics in Preschool Children with Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J. Dent. Sci. 2020, 15, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.; Zhang, J.; Pliska, B.; Amin, R.; Narang, I.; Chadha, N.; Cholette, M.-C.; Kirk, V.; Montpetit, A.; Vezina, K.; et al. Prevalence of Altered Craniofacial Morphology in Children with OSA. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e70060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, G.V.; Lakhe, P.; Niranjane, P. Maxillary Expansion and Its Effects on Circummaxillary Structures: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Si, M.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, R.; Hao, Z. Evolution, Current Status, and Future Trends of Maxillary Skeletal Expansion: A Bibliometric Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 28, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Park, Y.-C.; Lee, K.-J.; Lintermann, A.; Han, S.-S.; Yu, H.-S.; Choi, Y. Assessment of Changes in the Nasal Airway after Nonsurgical Miniscrew-Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Young Adults. Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Tang, H.; Liu, X.; Luo, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Martín, D.; Guo, J. Comparison of Dimensions and Volume of Upper Airway before and after Mini-Implant Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCosimo, C.; Alsulaiman, A.A.; Shah, C.; Motro, M.; Will, L.A.; Parsi, G.K. Analysis of Nasal Airway Symmetry and Upper Airway Changes after Rapid Maxillary Expansion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2021, 160, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsolakis, I.A.; Kolokitha, O.-E. Comparing Airway Analysis in Two-Time Points after Rapid Palatal Expansion: A CBCT Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, J.A.J.; Lione, R.; Franchi, L.; Angelieri, F.; Cevidanes, L.H.S.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Cozza, P. The Role of Rapid Maxillary Expansion in the Promotion of Oral and General Health. Prog. Orthod. 2015, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Di Carlo, G.; Cornelis, M.; Cattaneo, P. Three-Dimensional Analyses of Short- and Long-Term Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Nasal Cavity and Upper Airway: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 23, 250–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, L.; Hatzopoulos, S.; Catalano, A.; Bianchini, C.; Cammaroto, G.; Meccariello, G.; Iannella, G.; Vicini, C.; Pelucchi, S.; Skarżyński, P.; et al. Rapid Maxillary Expansion (RME): An Otolaryngologic Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Súcar, A.-M.; Sánchez-Súcar, F.-D.B.; Almerich-Silla, J.; Paredes-Gallardo, V.; Montiel-Company, J.; García-Sanz, V.; Bellot-Arcís, C. Effect of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome in Growing Patients. A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinzi, V.; Saccomanno, S.; Manenti, R.; Giancaspro, S.; Paskay, C.; Marzo, G. Efficacy of Rapid Maxillary Expansion with or without Previous Adenotonsillectomy for Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome Based on Polysomnographic Data: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, R.; Rongo, R.; Zunino, B.; Michelotti, A.; Bucci, P.; Alessandri-Bonetti, G.; Incerti-Parenti, S.; D’antò, V. Effect of Orthopedic and Functional Orthodontic Treatment in Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 67, 101730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, A.; Rodriguez, S.M.; Alsadi, T.H. The Role of Rapid Maxillary Expansion in the Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea: Monitoring Respiratory Parameters—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269, W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozek, J.L.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bowen, J.M.; Bucher, J.; Chiu, W.A.; Cronin, M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falavigna, M.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 30: The GRADE Approach to Assessing the Certainty of Modeled Evidence-An Overview in the Context of Health Decision-Making. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 129, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, O.; Lotfi, T.; Langendam, M.W.; Parmelli, E.; Saz Parkinson, Z.; Solo, K.; Chu, D.K.; Mathew, J.L.; Akl, E.A.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; et al. Good or Best Practice Statements: Proposal for the Operationalisation and Implementation of GRADE Guidance. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 2023, 28, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastuca, R.; Meneghel, M.; Zecca, P.A.; Mangano, F.; Antonello, M.; Nucera, R.; Caprioglio, A. Multimodal Airway Evaluation in Growing Patients after Rapid Maxillary Expansion. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2015, 16, 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Fastuca, R.; Perinetti, G.; Zecca, P.A.; Nucera, R.; Caprioglio, A. Airway Compartments Volume and Oxygen Saturation Changes after Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Longitudinal Correlation Study. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreaqat, M.; Hassan, R.; Alforaidi, S.; Kassim, N.K. Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Upper Airway Parameters in OSA Children with Maxillary Restriction: A CBCT Study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2024, 59, 2490–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabalan, O.; Gordon, J.; Heo, G.; Lagravère, M.O. Nasal Airway Changes in Bone-Borne and Tooth-Borne Rapid Maxillary Expansion Treatments. Int. Orthod. 2015, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Fastuca, R.; Portelli, M.; Militi, A.; Bellocchio, M.; Spinuzza, P.; Briguglio, F.; Caprioglio, A.; Nucera, R. Effects of Rapid vs Slow Maxillary Expansion on Nasal Cavity Dimensions in Growing Subjects: A Methodological and Reproducibility Study. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 18, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargani, F.; Magnuson, A.; Ludwig, B. Effects on Nasal Airflow and Resistance Using Two Different RME Appliances: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2018, 40, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottaviano, G.; Maculan, P.; Borghetto, G.; Favero, V.; Galletti, B.; Savietto, E.; Scarpa, B.; Martini, A.; Stellini, E.; De Filippis, C.; et al. Nasal Function before and after Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Children: A Randomized, Prospective, Controlled Study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 115, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garib, D.; Miranda, F.; Palomo, J.M.; Pugliese, F.; da Cunha Bastos, J.C.; Dos Santos, A.M.; Janson, G. Orthopedic Outcomes of Hybrid and Conventional Hyrax Expanders. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.C.; Dalci, O.; Mustac, S.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Hammond, S.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Papadopoulou, A.K. The Upper Airway Volume Effects Produced by Hyrax, Hybrid-Hyrax, and Keles Keyless Expanders: A Single-Centre Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2021, 43, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, G.; Gode, S.; Ozturk, A.; Kirazlı, T.; Veli, I. Evaluation of the Effects of Different Rapid Maxillary Expansion Appliances on Airway by Acoustic Rhinometry: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 155, 111074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Gandhi, V.; Vich, M.L.; Allareddy, V.; Tadinada, A.; Yadav, S. Long-Term Assessment of Conventional and Mini-Screw-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion on the Nasal Cavity. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, G.; Basoglu, O.K.; Veli, I. Polygraphic Evaluation of the Effects of Different Rapid Maxillary Expansion Appliances on Sleep Quality: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Sleep Breath. 2023, 27, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.; Massaro, C.; Garib, D. Comparison of Nasal Cavity Changes between the Expander with Differential Opening and the Fan-Type Expander: A Secondary Data Analysis from an RCT. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 5999–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vece, L.; Doldo, T.; Faleri, G.; Picciotti, M.; Salerni, L.; Ugolini, A.; Goracci, C. Rhinofibroscopic and Rhinomanometric Evaluation of Patients with Maxillary Contraction Treated with Rapid Maxillary Expansion. A Prospective Pilot Study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 42, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.N.C.; Rino-Neto, J.; Batista de Paiva, J. Acoustic Rhinometric Evaluation of the Nasal Cavity after Rapid Maxillary Expansion. South Eur. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Res. 2018, 5, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, N.; Basri, O.; Gadi, L.S.; Alhameed, A.F.; Grady, J.M. Parents’ Perceptions of Breathing Pattern Changes, Sleep Quality, and Fatigue in Children after Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Survey and Case Series Study. Open Dent. J. 2019, 13, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motro, M.; Schauseil, M.; Ludwig, B.; Zorkun, B.; Mainusch, S.; Ateş, M.; Küçükkeleş, N.; Korbmacher-Steiner, H. Rapid-Maxillary-Expansion Induced Rhinological Effects: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2016, 273, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, V.; Ghoneima, A.; Lagravere, M.; Kula, K.; Stewart, K. Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Airway Volume Changes in Two Expansion Activation Protocols. Int. Orthod. 2018, 16, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanteri, V.; Farronato, M.; Ugolini, A.; Cossellu, G.; Gaffuri, F.; Parisi, F.M.R.; Cavagnetto, D.; Abate, A.; Maspero, C. Volumetric Changes in the Upper Airways after Rapid and Slow Maxillary Expansion in Growing Patients: A Case-Control Study. Materials 2020, 13, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavand, G.; Lagravère, M.; Kula, K.; Stewart, K.; Ghoneima, A. Retrospective CBCT Analysis of Airway Volume Changes after Bone-Borne vs Tooth-Borne Rapid Maxillary Expansion. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastuca, R.; Lorusso, P.; Lagravère, M.O.; Michelotti, A.; Portelli, M.; Zecca, P.A.; D’ Antò, V.; Militi, A.; Nucera, R.; Caprioglio, A. Digital Evaluation of Nasal Changes Induced by Rapid Maxillary Expansion with Different Anchorage and Appliance Design. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdur, E.A.; Yıldırım, M.; Karatas, R.M.C.; Akin, M. Effects of Symmetric and Asymmetric Rapid Maxillary Expansion Treatments on Pharyngeal Airway and Sinus Volume. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, A.; Cavagnetto, D.; Fama, A.; Matarese, M.; Lucarelli, D.; Assandri, F. Short Term Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Breathing Function Assessed with Spirometry: A Case-Control Study. Saudi Dent. J. 2021, 33, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lie, S.A.; Hellén-Halme, K.; Shi, X.Q. Effect of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Upper Airway Morphology: A Retrospective Comparison of Normal Patients versus Patients with Enlarged Adenoid Tissue. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 45, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Chen, Y.; Hellén-Halme, K.; Cai, W.; Shi, X.-Q. The Effect of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on the Upper Airway’s Aerodynamic Characteristics. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; Lisciotto, E.; Caruso, S.; Marino, A.; Fiasca, F.; Buttarazzi, M.; Sarzi Amadè, D.; Evangelisti, M.; Mattei, A.; Gatto, R. Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expander and Delaire Mask Treatment on Airway Sagittal Dimensions in Pediatric Patients Affected by Class III Malocclusion and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Life 2023, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsivalle, V.; Leonardi, R.; Lagravere, M.; Flores-Mir, C.; Grippaudo, C.; Alessandri Bonetti, G.; Lo Giudice, A. Medium-Term Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Nasal Cavity and Pharyngeal Airway Volumes Considering Age as a Factor: A Retrospective Study. J. Dent. 2024, 144, 104934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badreddine, F.R.; Fujita, R.R.; Alves, F.E.M.M.; Cappellette, M.J. Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Mouth Breathers: A Short-Term Skeletal and Soft-Tissue Effect on the Nose. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 84, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, Y.; Brown, L.; Sonnesen, L. Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Upper Airway Volume: A Three-Dimensional Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawad, H.; Lee, K.-M.; Lim, H.-J. Three-Dimensional Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Retrospective Comparison with Propensity Score Matched Controls. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Motro, M.; Will, L.A.; Cornelis, M.A.; Cattaneo, P.M. Does Rapid Maxillary Expansion Enlarge the Nasal Cavity and Pharyngeal Airway? A Three-Dimensional Assessment Based on Validated Analyses. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 24, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Julián-López, C.; Veres, J.; Marqués-Martínez, L.; García-Miralles, E.; Arias, S.; Guinot-Barona, C. Upper Airway Changes after Rapid Maxillary Expansion: Three-Dimensional Analyses. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korayem, M.A. Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Upper Airway Volume in Growing Children: A Three-Dimensional Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e34274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellette, M.J.; Alves, F.E.M.M.; Nagai, L.H.Y.; Fujita, R.R.; Pignatari, S.S.N. Impact of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Nasomaxillary Complex Volume in Mouth-Breathers. Dental Press J. Orthod. 2017, 22, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuka, E.N.; Feres, M.F.N.; Pignatari, S.S.N. Immediate Impact of Rapid Maxillary Expansion on Upper Airway Dimensions and on the Quality of Life of Mouth Breathers. Dental Press J. Orthod. 2015, 20, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellette, M.J.; Nagai, L.H.Y.; Gonçalves, R.M.; Yuki, A.K.; Pignatari, S.S.N.; Fujita, R.R. Skeletal Effects of RME in the Transverse and Vertical Dimensions of the Nasal Cavity in Mouth-Breathing Growing Children. Dental Press J. Orthod. 2017, 22, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuzian, M.; Ju, X.; Almukhtar, A.; Ayoub, A.; Al-Muzian, L.; McDonald, J.P. Does Rapid Maxillary Expansion Affect Nasopharyngeal Airway? A Prospective Cone Beam Computerised Tomography (CBCT) Based Study. Surg. 2018, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariani, R.C.B.; Bigliazzi, R.; Medda, M.G.; Micieli, A.P.R.; Tufik, S.; Fujita, R.R.; de Mello, C.B.; Moreira, G.A. Changes in Behavioral and Cognitive Abilities after Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Children Affected by Persistent Snoring after Long-Term Adenotonsillectomy: A Noncontrolled Study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2024, 165, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, N.; Nambiar, S.; Desai, A.; Ahmed, J. Effect of Maxillary Expansion Treatment Protocols On Maxillary Sinus Volume, Pharyngeal Airway Volume, and Hyoid Bone Position: A Prospective, Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) Study. Open Dent. J. 2022, 16, e187421062208220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Saitoh, I.; Takemoto, Y.; Inada, E.; Kakuno, E.; Kanomi, R.; Hayasaki, H.; Yamasaki, Y. Tongue Posture Improvement and Pharyngeal Airway Enlargement as Secondary Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion: A Cone-Beam Computed Tomography Study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 143, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colino-Gallardo, P.; Del Fresno-Aguilar, I.; Castillo-Montaño, L.; Colino-Paniagua, C.; Baptista-Sánchez, H.; Criado-Pérez, L.; Alvarado-Lorenzo, A. Skeletal and Dentoalveolar Changes in Growing Patients Treated with Rapid Maxillary Expansion Measured in 3D Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Intervention (I) | |

|

|

|

|

| Comparison (C) | |

| |

| Outcomes (O) | |

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| Study Design (S) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| Other | |

|

|

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | ((“maxillary expansion”[Title/Abstract] OR “palatal expansion”[Title/Abstract] OR “maxillary constriction”[Title/Abstract] OR “narrow maxilla”[Title/Abstract] OR “transverse maxillary deficiency”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“airway”[Title/Abstract] OR “nasal breathing”[Title/Abstract] OR “airway obstruction”[Title/Abstract] OR “sleep apnea”[Title/Abstract] OR “airway volume”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“rapid maxillary expansion”[Title/Abstract] OR “rapid palatal expansion”[Title/Abstract] OR “RME”[Title/Abstract] OR “MARPE”[Title/Abstract] OR “miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion”[Title/Abstract])) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“maxillary expansion” OR “palatal expansion” OR “maxillary constriction” OR “narrow maxilla” OR “transverse maxillary deficiency”) AND ALL (“airway” OR “nasal breathing” OR “airway obstruction” OR “sleep apnea” OR “airway volume”) AND ALL (“rapid maxillary expansion” OR “rapid palatal expansion” OR “RME” OR “MARPE” OR “miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion”)) |

| ScienceDirect | (“maxillary expansion” OR “palatal expansion”) AND (“airway” OR “sleep apnea”) AND (“rapid maxillary expansion” OR “MARPE”) |

| Cochrane CENTRAL Library | (maxillary expansion OR palatal expansion OR transverse maxillary deficiency) AND (respiratory function OR airway obstruction OR nasal breathing OR sleep apnea) AND (rapid palatal expansion OR RPE OR MARPE OR RME) |

| Google Scholar | (“maxillary transverse deficiency” OR “maxillary constriction” OR “narrow maxilla” OR “posterior crossbite”) (“rapid palatal expansion” OR “RPE” OR “miniscrew-assisted rapid palatal expansion” OR “MARPE”) (“respiratory function” OR “airway volume” OR “nasal airflow” OR “sleep apnea”) |

| Study (Authors, Year) | Country | Study Design | Treatment Group | Treatment Type | Control Group | Outcomes Measured | Follow-Up Duration | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fastuca et al. (2015a) [35] | Italy | Prospective non-controlled longitudinal clinical study | 22 M = 9 F = 13 Mean age: 8.3 ± 0.9 | Haas-type maxillary expander | None | Airway volume (CBCT) Respiratory function metrics (spirometry, PSG) | 12 months (post-expansion, after appliance removal) | RME produced significant increases in total airway volume and clinically meaningful improvements in oxygen saturation (SpO2) and AHI in growing patients. However, changes in airway volume did not correlate with changes in SpO2 or AHI, indicating that anatomical enlargement alone does not predict respiratory benefit. |

| Fastuca et al. (2015b) [36] | Italy | Prospective non-controlled longitudinal clinical study | 15 M = 4 F = 11 Mean age: 7.5 ± 0.3 | Haas-type maxillary expander | None | Airway volume (CBCT) Respiratory function metrics (spirometry, PSG) | 12 months (post-expansion, after appliance removal) | RME produced significant morphological gains, increasing volumes of the upper, middle, and lower airway compartments. Patients with smaller baseline middle- and lower-airway volumes showed the greatest post-RME improvement in oxygen saturation (SpO2), indicating that baseline compartment size is a useful predictor of oxygenation benefit. Although AHI decreased overall, its change did not correlate with baseline airway dimensions, and morphology predicts SpO2 gains better than AHI response. |

| Izuka et al. (2015) [69] | Brazil | Prospective non-controlled clinical trial | 25 M = 11 F = 14 Mean age: 10.5 ± 2.2 | Modified Biederman-type appliance | None | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Transverse width of the nasal floor; - Nasopharynx and nasal cavities volume; - Oropharynx volume. Quality of Life Questionnaire | Immediate (≈3 weeks post-expansion) | RME is an effective treatment that not only produces significant dimensional changes in the upper airway, specifically in the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, but also markedly improves the overall quality of life for patients with mouth breathing and maxillary atresia. |

| Kabalan et al. (2015) [38] | Canada | RCT | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. Tooth-Borne (TB) Group: 20 (5 M, 15 F) with a mean age of 14.1 years. 2. Bone-Borne (BB) Group: 20 (8 M, 13 F) with a mean age of 14.2 years. | TB group: Hyrax tooth-borne appliance BB group: bone-integrated miniscrew implant bone- anchored maxillary expansion device | 21 M = 6 F = 15 Mean age: 12.9 ± unclear | Nasal airway dimensions (acoustic rhinometry and CBCT): - Minimum cross-sectional area; - Airway volume. | 6 months (after appliance removal) | RME (tooth-borne or bone-borne) did not yield consistent, clinically meaningful improvements in nasal airway dimensions or function. Changes in nasal airway volume and function were minor, variable, and sometimes negative, indicating that any observed improvements were likely coincidental rather than treatment-related. RME should not be used with the primary goal of improving nasal airway function, as its effects are inconsistent and lack long-term predictability. |

| Motro et al. (2016) [51] | USA Germany | Retrospective multicenter comparative study | 31 M = 12 F = 19 Mean age: 14.63 ± 0.38 Based on the RME appliance type: 1. Hyrax Group: 5 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 13.80 ± 0.12 years. 2. Acrylic Cap Group: 20 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 14.05 ± 0.31 years. 3. Hybrid Group: 6 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 17.25 ± 1.26 years. | 1. Hyrax-type 2. Acrylic Cap-type 3. Hybrid-type (combination of molar bands with a skeletal anchorage unit) | None | Airway volume (CBCT): - Total airway volume; - Nasopharynx; - Oropharynx; - Laryngopharynx. | Immediate (≈25 days post-expansion) | RME produced significant enlargement of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal volumes, confirming a robust upper-airway response to expansion. No meaningful change in the laryngopharyngeal airway was detected, indicating the effect is primarily confined to superior airway levels. Therapeutic gains were comparable across appliance types and ages; Hybrid RME achieved airway improvements similar to those of tooth-borne designs, despite being used in older patients. |

| Cappellette et al. (2017a) [68] | Brazil | Prospective controlled clinical study | 23 M = 12 F = 11 Mean age: 9.6 ± 2.3 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 15 M = 9 F = 6 Mean age: 10.5 ± 1.9 | Airway volume (CT): - Total nasomaxillary complex; - Nasal cavity; - Oropharynx. | 3 months (post-retention) | RME produced a significant 3D volumetric enlargement of the nasomaxillary complex in mouth-breathing patients with transverse maxillary deficiency. Structure-specific gains were documented in the nasal cavity, oropharynx, and both maxillary sinuses, indicating a widespread morphologic response. RME is an effective intervention to increase airway-related volumes in this population, while functional benefits should be assessed separately. |

| Cappellette et al. (2017b) [70] | Brazil | Prospective non-controlled clinical study | 61 M = 35 F = 26 Mean age: 9.6 ± unclear | Modified Hyrax expander, tooth-anchored | None | Skeletal and nasal dimension changes (PA cephalometric radiographs): - Nasal width; - Nasal height; - Nasal area. | 3 months (post-RME) | RME produced significant increases in all transverse linear measurements of the maxilla and nasal cavity, alongside greater nasal cavity volume, supporting improved airflow and favorable craniofacial growth. RME was equally effective in boys and girls, and maxillary constriction showed no association with sex. |

| Fastuca et al. (2017) [55] | Italy | Retrospective comparative study | 44 M = 20 (mean age: 8 years and 8 months ± 1 years and 2 months) F = 24 (mean age: 8 years and 2 months ± 1 years and 4 months) Based on the RME appliance type: 1. HX-6 Group: 15 (gender not specified), mean age not specified. 2. HX-E Group: 14 (gender not specified), mean age not specified. 3. HS-E Group: 15 (gender not specified), mean age not specified. | 1. HX-6 Group: Hyrax expander anchored to permanent teeth; 2. HX-E Group: Modified Hyrax expander anchored to deciduous teeth; 3. HS-E Group: Modified Haas-type expander anchored to deciduous teeth. | None | Nasal cavity dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal floor width; - Nasal wall width. | 7 months (post-retention) | The study investigates the effects of RME with different appliance designs and anchorage methods. RME effectively produces a significant skeletal transverse expansion of the nasal region in growing patients. The study found that no significant differences in nasal effects are expected whether the RME appliance is anchored onto deciduous teeth, with or without palatal acrylic coverage. This suggests that the choice between permanent or deciduous tooth anchorage, or the specific design of the expander, does not result in a statistically significant difference in terms of nasal expansion. |

| Lo Giudice et al. (2017) [39] | Italy | RCT | Based on the type of maxillary expansion: 1. RME group: 10 (6 M, 4 F) with a mean age of 10.4 ± 1.72 years. 2. SME group: 10 (4 M, 6 F) with a mean age of 10.5 ± 1.41 years. | Hyrax-type expander | None | Nasal cavity dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity width; - Total nasal volume. | 7 months (post-retention) | Both RME and SME effectively increased the dimensions of the nasal cavity. Skeletal expansion relative to dental expansion is a better indicator of protocol efficacy than absolute NW values. |

| Almuzian et al. (2018) [71] | UK | Prospective non-controlled clinical study | 17 M = 8 F = 9 Mean age: 12.6 ± 1.8 | A cast-cap appliance that incorporated a Hyrax screw | None | Volumetric changes of the upper nasopharyngeal airway spaces (CBCT): - Lower nasal cavity; - Upper nasopharynx; - Retropalatal (velo-pharyngeal) space. | Immediate (≈23 days post-expansion) | RME was found to be an effective dentoalveolar expander in growing patients. Upper nasopharynx volume increases after RME, while the upper retropalatal space decreases. Airway change follows a mushroom-like pattern with superior enlargement and midlevel narrowing. |

| Badreddine et al. (2018) [62] | Brazil | Retrospective controlled study | 39 M = 23 F = 16 Mean age: 9.7 ± 2.28 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 16 M = 9 F = 7 Mean age: 8.8 ± 2.17 | Skeletal and soft tissue variables of the nasal cavity (CBCT) | 3 months (post-retention) | RME produces significant short-term changes in nasal skeletal and soft-tissue structures in mouth-breathing children. Soft-tissue response closely mirrors skeletal expansion, with approximately 0.95 mm of soft tissue per 1 mm of skeletal increase. Findings support incorporating nasal soft-tissue effects into aesthetic planning for the nasal tip and base. |

| Barzagani et al. (2018) [40] | Germany | RCT | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. TB group: 19 (11 M, 8 F) with a mean age of 9.7 ± 1.5 years. 2. TBB group: 21 (10 M, 11 F) with a mean age of 10.2 ± 1.4 years. | TB group: conventional tooth-borne appliance TBB group: bone-integrated miniscrew implant bone- anchored maxillary expansion device | None | Nasal airflow and resistance (active anterior rhinomanometry, AAR) | Immediate (post-expansion) | Tooth–bone–borne RME produced higher nasal airflow and lower nasal resistance than tooth-borne RME. Findings support TBB RME when maxillary constriction coexists with upper airway obstruction. Expected benefit focuses on nasal breathing performance rather than appliance-specific skeletal expansion. |

| Di Vece et al. (2018) [48] | Italy | Prospective pilot study | 30 M = 12 F = 18 Mean age: 8.7 ± 0.9 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Nasopharynx obstruction (rhinofibroscopy) Nasal airway resistance (rhinomanometry) | 6 months (post-retention, after appliance removal) | RME reduces nasal resistance and the degree of nasopharyngeal obstruction, indicating a measurable physiological benefit for the upper airways. Upper airway patency improves after expansion, with the greatest value in patients with mild to moderate nasal obstruction. RME is adjunctive rather than a replacement for indicated medical therapy or adenoidectomy. |

| Lotfi et al. (2018) [52] | USA | Retrospective study | Based on the RME activation rates: 1. Group A (Higher Activation Rate, 0.8 mm/day activation): 20 (8 M, 12 F) with a mean age of 12.3 ± 1.9 years. 2. Group B (Slower Activation Rate, 0.5 mm/day activation): 20 (10 M, 10 F) with a mean age of 13.8 ± 1.3 years. | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Airway volume (CBCT): - Nasal cavity; - Nasopharynx; - Oropharynx; - Hypopharynx. | 3 months (post-retention) | Airway volume change after RME is rate-dependent, with faster activation producing larger gains. Nasal cavity and nasopharynx volumes increase more with rapid activation than with slower protocols. Findings support modulating activation speed when prioritizing upper-airway enlargement in constricted patients. |

| Ottaviano et al. (2018) [41] | Italy | RCT | 11 Gender: not specified Mean age: 8.27 ± 1.62 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 11 Gender: not specified Mean age: 8.27 ± 1.25 | Nasal respiratory function: - Nasal flow and patency (Peak Nasal Inspiratory Flow, PNIF); - Nasal resistance (AAR). | Immediate post-expansion or 1 month after enrolment (for control group); 6 months | RME enhances nasal physiology, with higher PNIF immediately and at six months, and improved N-butanol olfactory threshold. The likely mechanism is increased nasal airflow rather than measurable changes in standard resistance metrics. No significant change in nasal resistance on AAR. Clinically useful for managing crossbite in growing children while conferring ancillary benefits in airflow and smell perception. |

| Ribeiro et al. (2018) [49] | Brazil | Prospective observational study | 19 M = 10 F = 9 Mean age: 8.9 ± unclear | Modified Biederman dento-supported expander type | None | Nasal cavity geometry (CBCT): - Minimum cross-sectional areas; - Nasal space volumes. - Nasal cavity patency (AR) | 1 week after expansion; 6 months | Immediate enlargement of the anterior nasal cavity after RME, with regression toward baseline after the containment period. Nasal dimensional gains are short-lived and mainly anterior, with limited long-term impact on cross-sectional area. Primary indication remains correction of dentoalveolar problems rather than respiratory therapy. |

| Abdalla et al. (2019) [63] | Denmark Australia | Retrospective controlled clinical study | 26 M = 12 F = 14 Mean age: 12.3 ± 2.3 | TB Hyrax-type expander | 26 M = 12 F = 14 Mean age: 12.33 ± 2 | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Minimal cross-sectional area; - Pharyngeal airway volume. | ≈35 months (matched with controls) | Tooth-borne RME did not yield a significant increase in upper pharyngeal airway volume or minimal cross-sectional area versus controls, despite clear gains in intermolar and maxillary widths. Skeletal age was a significant predictor of airway change, with younger skeletal age showing more favorable airway responses. Dental and skeletal widening does not necessarily translate to upper-airway enlargement. |

| Helal et al. (2019) [50] | USA | Prospective observational study | 91 M = 49 F = 42 Mean age: 7.6 ± 5 | bonded Hyrax expander | None | Parental perceptions (16-item questionnaire) Nasal cavity dimensions (CBCT) | 12 months (including 6-month interim assessment) | Parents reported better behavior, less daytime fatigue, and improved sleep and breathing after RME. Perceived gains were most evident for behavior and fatigue, with smaller but present improvements in sleep quality and breathing. CBCT models confirmed increased nasal cavity size, supporting a structural basis for breathing improvements. |

| Kavand et al. (2019) [54] | USA | Retrospective comparative study | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. Tooth-Borne (TB) Group: 18 (8 M, 10 F) with a mean age of 14.4 ± 1.3 years. 2. Borne-borne (BB) Group: 18 (6 M, 12 F) with a mean age of 14.7 ± 1.4 years. | TB group: Hyrax-type expander BB group: two palatal miniscrews connected to a jackscrew | None | Upper airway volume (CBCT): - Nasal cavity; - Nasopharynx; - Oropharynx; - Maxillary Sinus. | 3 months (post-retention) | Both tooth-borne and bone-borne RME increased nasal cavity and nasopharynx volumes in adolescents. No meaningful intergroup difference in airway volume change was detected. Bone-borne RME may be preferred when aiming to minimize dentoalveolar side effects while achieving similar airway gains. |

| Erdur et al. (2020) [56] | Turkey | Retrospective comparative study | Based on the RME type: 1. Symmetric RME Group: 30 (16 M, 14 F) with a mean age of 14.04 years. 2. Asymmetric (ARME) Group: 30 (14 M, 16 F) with a mean age of 13.75 years. | RME group: Hyrax-type rapid expander ARME group: modified acrylic bonded appliances with an occlusal-lock mechanism on the unaffected side and with a Hyrax screw | None | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Pharyngeal airway volumes; - Maxillary sinus volume. | 3 months (post-retention) | Both symmetric RME and asymmetric ARME increased pharyngeal airway and maxillary sinus volumes. RME was effective for patients with bilateral maxillary deficiency. ARME effectively corrected true unilateral posterior crossbite and also increased airway and sinus volumes. Both protocols achieved meaningful orthopedic widening with favorable volumetric airway changes. |

| Lanteri et al. (2020) [53] | Italy | Retrospective case–control CBCT study | Based on the maxillary expansion appliance type: 1. Slow Maxillary Expansion (SME) Group: 22 (9 M, 13 F) with a mean age of 8.2 ± 0.6 years. 2. Rapid Maxillary Expansion (RME) Group: 22 (11 M, 11 F) with a mean age of 8.1 ± 0.7 years. | SME group: Leaf Expander RME group: Hyrax expander | None | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity; - Nasopharynx; - Maxillary sinus. | ≈11 months (range 10–14 months, post-retention) | Slow maxillary expansion (SME) is effective for treating maxillary hypoplasia in mixed dentition. SME increases pharyngeal airway volume and maxillary sinus volumes. SME and conventional Hyrax-type RME show comparable airway and sinus gains, with no significant differences. Both SME and RME enlarge the upper-airway and maxillary sinus volumes in growing patients. |

| Abate et al. (2021) [57] | Italy | Retrospective case–control clinical study | Based on the baseline breathing patterns: 1. Oral Breathes: 25 (12 M, 13 F) with a mean age of 15.2 ± 1.3 years. 2. Nasal Breathers: 25 (11 M, 14 F) with a mean age of 14.9 ± 1.7 years. | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Nasal respiratory function (spirometry): - Forced vital capacity; - Forced expiratory volume in the first second; - Tiffenau index; - Forced expiratory flow at 25–75% of vital capacity; - Tidal volume. | 6 months after RME; 12 months after RME | RME improved breathing function in both oral and nasal breathers. Oral breathers showed greater gains, with significant increases in FEV1 and the Tiffenau Index, likely due to reduced peripheral airway resistance. In oral breathers, FVC, FEF25–75%, and tidal volume increased to values comparable to those of nasal breathers. Improvements were largely sustained, with no between-group differences in spirometric indices at 12 months. |

| Aljawad et al. (2021) [64] | Korea | Retrospective controlled clinical study | 17 M = 3 F = 14 Mean age: 12.6 ± 1.8 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 17 M = 4 F = 13 Mean age: 12.3 ± 1.5 | Upper airway volume (CBCT): - Nasopharynx; - Oropharynx; - Minimal cross-sectional area. | ≈10.5 months (post-retention) | RME produced significant increases in upper airway dimensions in the treated group, while matched controls showed no meaningful change. Overall post-treatment gains in airway volumes and cross-sections were greater with RME than in controls. The oropharyngeal segment improved, with a statistically significant rise in minimum cross-sectional area, most clearly at the retropalatal level. Findings support RME as an effective intervention for enlarging upper airway dimensions beyond natural growth. |

| Cheung et al. (2021) [43] | Australia | RCT | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. Hyrax Group: 19 (10 M, 9 F) with a mean age of 13.8 years. 2. Hybrid-Hyrax Group: 19 (8 M, 11 F) with a mean age of 14.3 years. 3. Keles Group: 13 (2 M, 11 F) with a mean age of 14.6 years. | Hyrax Group: conventional Hyrax expander Hybrid-Hyrax Group: tooth-bone-borne device Keles Group: Keles keyless expander | None | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Total airway volume; - Nasal cavity volume; - Nasopharynx volume; - Oropharynx volume; - Hypopharynx volume. | 6 months (post-retention) | RME produced only small increases in total upper airway volume across devices, ranging from 3.8% with Hyrax to 8.3% with Hybrid-Hyrax and 4.5% with Keles. No significant inter-appliance differences were detected for overall volume or most airway compartments. The nasopharynx was the only compartment showing a significant intergroup difference. Patients with smaller baseline airway volumes exhibited greater post-expansion gains. In pre-peak growth patients, Hybrid-Hyrax achieved significantly larger total airway volume increases than conventional Hyrax |

| DiCosimo et al. (2021) [21] | USA | Retrospective controlled observational study | 28 M = 11 F = 17 Mean age: 9.86 ± 2.43 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 20 M = 9 F = 11 Mean age: 10.41 ± 1.60 | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity volumes; - Nasopharyngeal volume; - Oropharyngeal volume; - Minimum cross-sectional widths. | 24 months (post-RME) | RME produces significant and lasting improvements in upper airway dimensions. Patients showed a clear increase in nasal volume, minimum cross-sectional width, and nasopharyngeal volume compared with the control group. RME also contributed to improved nasal cavity symmetry by reducing the volume difference between the right and left nasal sides over time. |

| Feng et al. (2021a) [58] | Sweden | Comparative retrospective study | 17 M = 11 F = 6 Mean age: 12.2 ± 1.3 Based on adenoidal nasopharyngeal (AN) ratio: 1. Group 1 (AN ratio < 0.6, normal adenoids): 10 with a mean age of 11.9 ±1.29 years. 2. Group 2 (AN ratio ≥ 0.6, enlarged adenoids): 7 with a mean age of 12.6 ± 1.27 years. | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Upper airway morphology (CBCT): - Nasopharynx; - Retropalatal; - Retroglossal. | 5.7 months (post-retention) | RME showed only a modest, non-significant tendency to enlarge the nasopharyngeal airway, with the signal more apparent in children with adenoid hypertrophy. The AN ratio trended downward (less obstruction) but did not reach statistical significance. Upper-airway dimensional changes were small and inconsistent, suggesting limited morphological impact in the short term. RME may have a modest morphological influence on AH patients, but the effects were not statistically robust and should not be relied upon to reduce nasopharyngeal obstruction. |

| Feng et al. (2021b) [59] | China | Cohort retrospective | 17 M = 11 F = 6 Mean age: 12.2 ± 1.3 Based on the AN ratio: 1. Group 1 (AN ratio < 0.6); 2. Group 2 (AN ratio ≥ 0.6). | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Aerodynamic characteristics of the upper airway | ≈5.2 ± 1.7 months (including active expansion + retention) | No significant change in airflow dynamics after RME, with CFD metrics (pressure drop, peak velocity, wall shear stress) remaining statistically unchanged. Any numerical reductions observed did not reach significance, suggesting short-term morphologic widening may not translate into measurable aerodynamic improvement. |

| Garib et al. (2021) [42] | Brazil | RCT | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. HH Group: 18 (10 M, 8 F) with a mean age of 10.80 ± 1.04 years. 2. (CH) Group: 14 (8 M, 6 F) with a mean age of 11.44 ± 1.26 years. | HH Group: Hybrid-Hyrax tooth-bone-borne device CH Group: Conventional Hyrax expander | None | Nasal airway dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity width. | ~11.38 months (HH group) and ~11.00 months (CH group) | Hybrid Hyrax achieved greater orthopedic widening at superior levels, with larger increases in nasal cavity and maxillary widths. |

| Niu et al. (2021) [65] | Denmark USA | Retrospective controlled clinical study | 39 Gender: not specified Mean age: 10.40 ± 1.74 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 29 Gender: not specified Mean age: 11.07 ± 1.45 | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity volume; - Pharyngeal airway total volume; - Partial PA volumes; - Minimal Cross-Sectional Area. | ≈22.6 months (matched with controls) | RME significantly increases nasal cavity volume, with effects most evident when palatal width expansion exceeds 2 mm. Pharyngeal airway volume shows no net advantage over controls; within-group increases mainly reflect normalization rather than true surplus gain. Minimal cross-sectional area and minimal hydraulic diameter, initially reduced in RME patients, normalize to control levels after treatment. |

| Gokce et al. (2022) [44] | Turkey | RCT | 46 M = 16 F = 30 Mean age: 12.8 ± 1.2 Based on the RME appliance type: 1. Tooth Tissue-Borne (TTB) Group: 15 (3 M, 12 F) with a mean age of 12.5 years. 2. Tooth-Borne (TB) Group: 15 (9 M, 6 F) with a mean age of 12.8 years. 3. Bone-Borne (BB) Group: 16 (3 M, 13 F) with a mean age of 13.1 years. | Hyrax expansion screw with or without mini-screws | None | Nasal airway dimensions (AR): - Minimum cross-sectional area; - Nasal cavity volume. | Immediate (post-expansion); 3 months (post-retention) | All three expanders (tooth-tissue-borne, tooth-borne, and bone-borne) significantly increased nasal volume and minimal cross-sectional area. Magnitude of nasal airway gains was comparable across appliance designs, with no meaningful between-group differences. Enlarged nasal dimensions were maintained at short-term follow-up. Appliance selection can prioritize other clinical factors since nasal airway outcomes were equivalent. |

| Mehta et al. (2022) [45] | USA | RCT | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. MARPE Group: 20 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 13.69 ± 1.74 years. 2. RPE Group: 21 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 13.9 ± 1.14 years. | MARPE Group: Mini-screw-assisted expander RPE Group: Conventional tooth-borne expander | 19 Gender: not specified Mean age: 13.3 ± 1.49 | Nasal airway morphology (CBCT): - Nasal cavity dimensions; - Nasal widths. | Time period T1 (post-expansion) to T2 (post-treatment): - MARPE group (2 years 7 months); - RPE group (2 years 9 months); - Control group (2 years 7 months). | Both MARPE and RPE effectively widened the nasal cavity, with MARPE showing superior long-term skeletal stability. In the short term, both appliances significantly increased the alar base width and the posterior and anterior nasal cavity widths compared with the controls. In the long term, MARPE demonstrated a sustained increase in posterior nasal cavity width, suggesting more stable skeletal expansion than RPE. MARPE provides a more stable and lasting skeletal expansion, making it a preferable option for long-term airway and structural enhancement. |

| Shetty et al. (2022) [73] | India | Prospective non-randomized clinical study | Based on the treatment protocols for maxillary expansion: 1. RME Group: 8 (4 M, 4 F) with a mean age of 12.5 ± 1.3 years. 2. Alt-RAMEC (Alternate RME and Constriction) Group: 7 (5 M, 2 F) with a mean age of 10.4 ± 1.8 years. | RME group: Hyrax-type expander Alt-RAMEC Group: Hyrax-type expander and Petit Face mask | None | Airway volume (CBCT): - Maxillary sinus; - Pharyngeal volume; - Hyoid bone position. | RME group: 5 months (post-retention); Alt-RAMEC group: 3 months (post-retention) | Both RME and Alt-RAMEC protocols significantly increase maxillary sinus volume, while producing no meaningful changes in pharyngeal airway dimensions or hyoid bone position. RME showed a greater effect than Alt-RAMEC, suggesting a stronger role in craniofacial development, although differences in pharyngeal airway volume and hyoid bone position were not statistically significant. |

| Caruso et al. (2023) [60] | Italy | Retrospective clinical study | 14 M = 6 F = 8 Mean age: 8 ± 1 | Hyrax-type rapid expander and Delaire mask | None | Upper airway dimensions (cephalometric linear measurements): - Nasopharynx; - Oropharynx; - Hypopharynx. | 18 months: - RME phase for 12 months; - Delaire mask for 6 months; - 2 months after mask removal. | Combined therapy increases sagittal dimensions of the nasopharynx and oropharynx. Airway patency improves alongside OSAS-related clinical conditions. Protocol appears effective for Class III children with concomitant OSAS. |

| de Juliàn-Lòpez et al. (2023) [66] | Spain | Retrospective controlled clinical study | 37 M = 19 F = 18 Mean age: not specified | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 13 M = 5 F = 8 Age: not specified | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT) | RME group: ≈1.4 years; Control: ≈1.9 years | RME significantly increases upper airway volume in growing patients, producing a gain greater than expected from natural growth alone. |

| Gokce et al. (2023) [46] | Turkey | RCT | 46 M = 16 F = 30 Mean age: not specified Based on the RME appliance type: 1. TTB Group: 15 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 12.5 years. 2. TB Group: 15 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 12.8 years. 3. BB Group: 16 (gender not specified) with a mean age of 13.1 years. | TTB Group: Acrylic-covered occlusal, palatal, and buccal tooth surfaces. TB Group: Hyrax screw soldered to bands on molars/premolars. BB Group: Mini-screw-assisted expander | None | Airway patency and breathing quality during sleep: - AHI; - Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI); - Minimum oxygen saturation; - Supine AHI. | 3 months (post-retention) | RME did not improve OSA severity (no meaningful change in AHI/ODI/minimum SpO2). No between-appliance differences in sleep outcomes were detected. All appliance types produced similar skeletal/dental maxillary expansion, but this did not translate into improvements in PSG. RME alone should not be relied upon as an OSA therapy; adjunctive or alternative management is recommended. |

| Korayem et al. (2023) [67] | Saudi Arabia | Retrospective controlled clinical study | 52 Gender: not specified Mean age: not specified | Hyrax-type rapid expander | 52 Gender: not specified Mean age: not specified | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Volume; - Minimum cross-sectional area. | 6 months (post-retention) | RME does not produce a significant additional increase in upper airway volume or MCA compared to natural growth in untreated controls. However, younger patients, with an earlier skeletal age at the onset of treatment, tended to show more favorable airway adaptations, suggesting that early intervention may have a greater positive impact. |

| Teixeira et al. (2023) [47] | Brazil | RCT | Based on the RME appliance type: 1. Expander with Differential Opening (EDO) Group: 24 (11 M, 13 F) with a mean age of 7.6 ± 0.9 years. 2. Fan-Type Expander (FE) Group: 24 (10 M, 14 F) with a mean age of 7.8 ± 0.9 years. | EDO Group: appliance with two screws: anterior and posterior regions of the palate. FE Group: appliance with one anterior screw with a posterior hinge. | None | Nasal cavity dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity width; - Nasal cavity height. | 6 months (post-retention) | Both expanders enlarged skeletal nasal cavity dimensions in growing patients. EDO achieved greater transverse widening in the lower third of the nasal cavity, both anterior and posterior. Middle and upper nasal widths increased similarly with EDO and FE. Nasal cavity height changes were comparable between devices. EDO may be preferred when prioritizing inferior nasal airway enlargement (e.g., oral breathing/OSA), while either device is suitable for general nasal widening. |

| Tsolakis et al. (2023) [22] | Greece | Prospective non-controlled clinical trial | 14 M = 6 F = 8 Mean age: 10.82 ± 11.34 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Upper airway dimension (CBCT): - Volume; - Minimum cross-sectional area. | T1: Post-expansion (immediately after RPE) T2: 6 months post-expansion (retention) | RPE significantly increased both airway volume and MCA. Although airway volume slightly decreased after the six-month retention period, it remained higher than before treatment. The MCA showed a stable, sustained improvement, indicating that RPE effectively enhances and maintains nasal airway patency over time. |

| Bariani et al. (2024) [72] | Brazil | Prospective non-controlled clinical trial | 24 M = 16 F = 8 Mean age: 10 ± 1.8 Based on OAHI values: 1. Primary Snoring group (PS, OAHI value <1): 13 (9 M, 4 F) with a mean age of 10.3 ± 1.7 years; 2. Obstructive Sleep Apnea group (OSA, OAHI value ≥1): 11 (7 M, 4 F) with a mean age of 9.7 ± 1.8 years. | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Respiratory function metrics: - PSG parameters. - Quality of life (QOL) questionnaires. | 6 months (post-retention) | Treating SDB remains essential given symptoms/behavior linked to OAHI. RME is a plausible adjunct/alternative for children with persistent SDB and maxillary transverse deficiency. In the OSA subgroup, RME was associated with better quality of life and improvements in somatic complaints, aggressiveness, and visuospatial memory. |

| Ronsivalle et al. (2024) [61] | Italy | Retrospective cohort study | Based on two age-defined treatment groups: 1. Early Expansion Group (EEG): 25 (11 M, 14 F) with a mean age of 8.6 ± 1.1 years. 2. Late Expansion Group (LEG): 23 (10 M, 13 F) with a mean age of 12.2 ± 1.2 years. | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity volume; - Pharyngeal airway total volume; - Partial PA volumes; - Minimal cross-sectional area. | 12 months (including 6 months retention) | At 12 months, both early (EEG) and late (LEG) groups showed significant increases in nasal cavity and total pharyngeal airway volumes. Nasopharynx, velopharynx, and oropharynx volumes all increased in both cohorts; CSmin and palatal width also rose. Increases were larger in younger patients, with a notably greater nasopharyngeal gain in the EEG. Deviation analysis suggests that part of the nasopharyngeal enlargement reflects reduced adenotonsillar tissue, more evident on the EEG. |

| Zreaqat et al. (2024) [37] | Malaysia | Prospective longitudinal study | 47 M = 29 F = 18 Mean age: 10.29 ± 1.21 | Hyrax-type rapid expander | None | Upper airway dimensions (CBCT): - Nasal cavity volume; - Nasopharynx volume; - MCA. Respiratory parameters (PSG). | 6 months (post-retention) | RME is an effective therapeutic option for children with obstructive sleep apnea and maxillary constriction. The treatment produced significant improvements in upper airway dimensions, particularly in the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, along with notable enhancements in respiratory function. Increases in airway volume and reductions in respiratory disturbances suggest that RME can contribute to better sleep quality and breathing efficiency in pediatric patients. |

| OUTCOMES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Airway Morphology | Breathing Function | |

| Number of studies (participants) | 33 studies (1379 patients) | 14 studies (509 patients) |

| Study design | Mainly observational study; six RCTs | Mainly observational study; four RCTs |

| Risk of Bias | Not serious a | Not serious a |

| Inconsistency | Not serious b | Serious c |

| Indirectness | Not serious d | Serious e |

| Imprecision | Not serious f | Serious g |

| Publication of bias | Not serious h | Not serious h |

| Effect of direction | Consistent improvement (≈88% of studies show enlargement; no study shows worsening) | Overall favorable (≈71% positive; ≈29% neutral/mixed; no study shows worsening) |

| Overall GRADE certainty | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ierardo, G.; Nicita, F.; Vozza, I.; Polimeni, A.; Luzzi, V. Relationship Between Maxillary Transverse Deficiency and Respiratory Problems: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Devices over the Past Decade. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8861. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248861

Ierardo G, Nicita F, Vozza I, Polimeni A, Luzzi V. Relationship Between Maxillary Transverse Deficiency and Respiratory Problems: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Devices over the Past Decade. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8861. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248861

Chicago/Turabian StyleIerardo, Gaetano, Fabiana Nicita, Iole Vozza, Antonella Polimeni, and Valeria Luzzi. 2025. "Relationship Between Maxillary Transverse Deficiency and Respiratory Problems: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Devices over the Past Decade" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8861. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248861

APA StyleIerardo, G., Nicita, F., Vozza, I., Polimeni, A., & Luzzi, V. (2025). Relationship Between Maxillary Transverse Deficiency and Respiratory Problems: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Devices over the Past Decade. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8861. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248861