Effectiveness of Pharmacological Treatments for Adult ADHD on Psychiatric Comorbidity: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

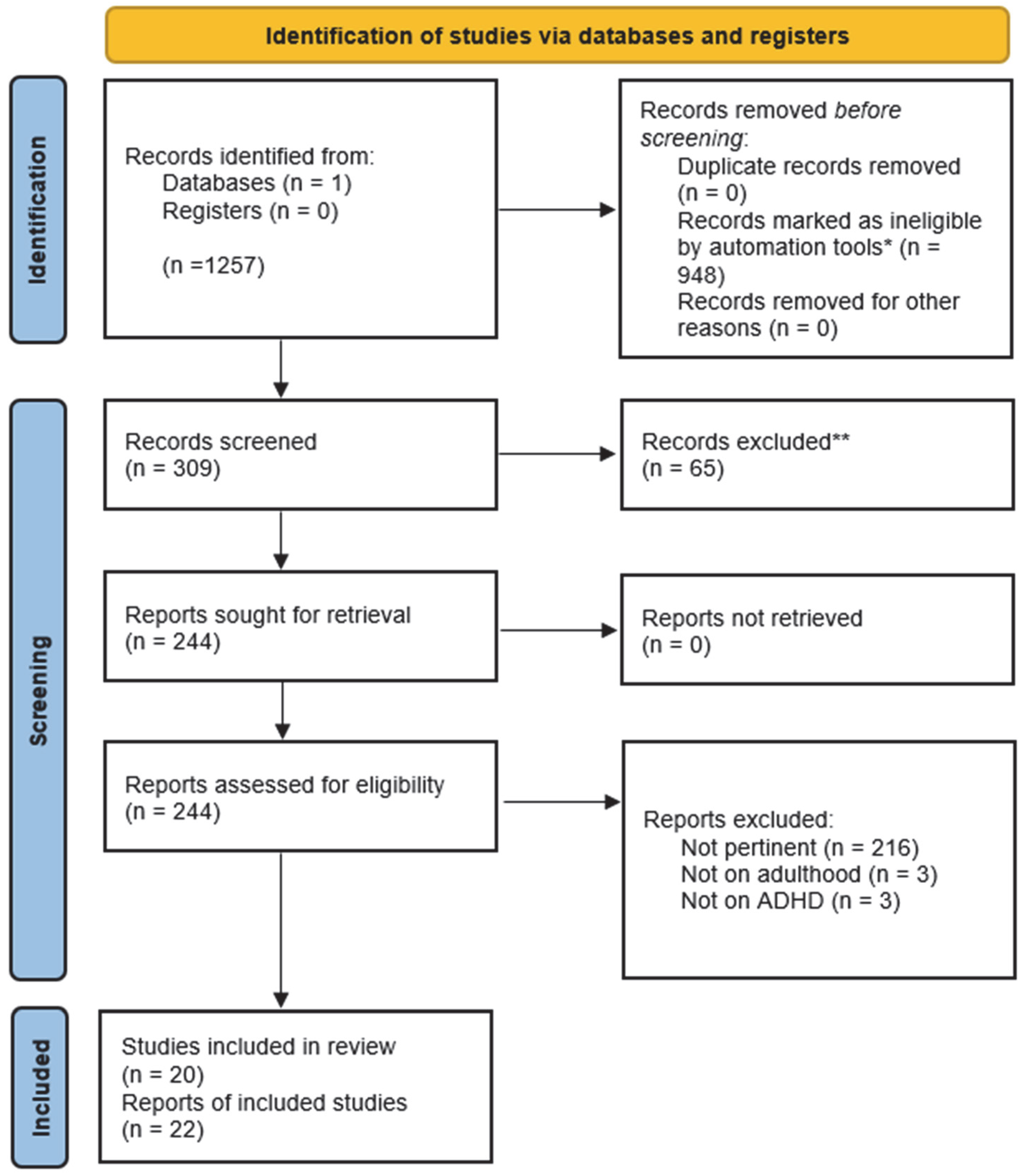

2. Materials and Methods

- P: The study population encompassed both female and male patients aged 18 years or older who met the established clinical criteria for ADHD and at least one psychiatric comorbidity.

- I: The intervention under investigation was psychopharmacological treatment for adults diagnosed with ADHD.

- C: The study considered comparisons between patients with ADHD and comorbidity before and after psychopharmacological treatment; matched groups treated with alternative forms of treatment (when available), control groups (when available).

- O: The primary outcome of interest was the change in the severity of general psychiatric symptoms.

- S: The review included a range of study designs, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, follow-up studies, pilot studies, quasi-experimental studies, case series, and case reports.

3. Results

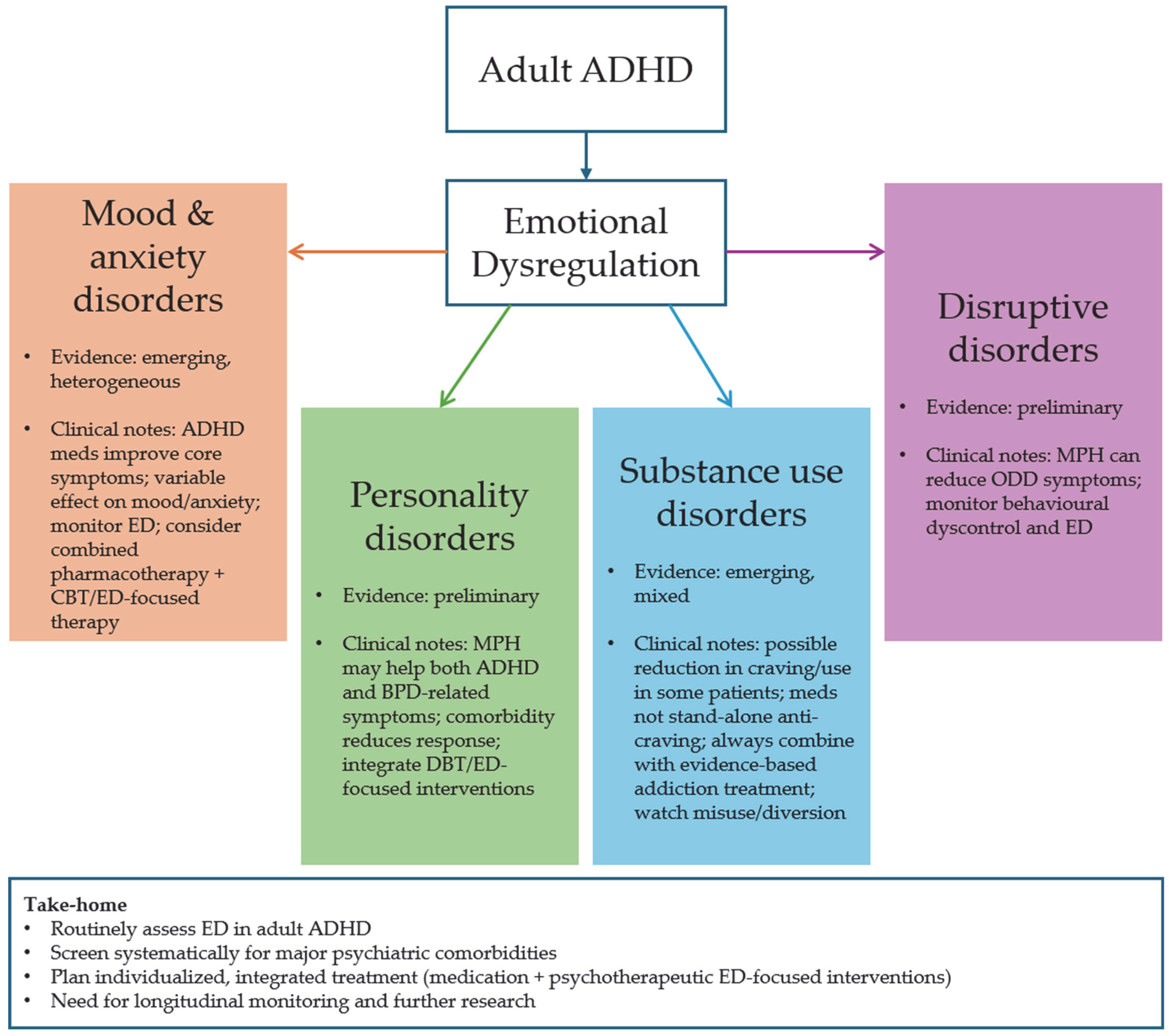

4. Discussion

4.1. Comorbidity of ADHD and Affective Disorders, and Anxiety and Panic Spectrum Disorders

4.2. Comorbidity of ADHD and Personality Disorders

4.3. Comorbidity of ADHD and Substance Use Disorder

4.3.1. ADHD Medication and Cocaine Dependence

4.3.2. ADHD Medication and Amphetamine Dependence

4.3.3. ADHD Medication and Alcohol and Nicotine Use

4.4. Comorbidity of ADHD and Disruptive Disorders

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ↑ | better |

| ↓ | worse |

| AAQoL | Adult ADHD Quality of Life Scale |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ADHD-RS | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale |

| AEP | Liverpool Adverse Events Profile |

| AES | Apathy Evaluation Scale |

| AISRS | Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Report Scale |

| ARS | ADHD Rating Scale |

| ARS-IV | ADHD Rating Scale-IV |

| ASI | Addiction Severity Index |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ASRS | Adult Self-Report Scale |

| ATX | Atomoxetine |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| BD | Bipolar Disorder |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Edition |

| BPD | Borderline Personality Disorder |

| BSCS | Brief Substance Craving Scale |

| CAARS | Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale |

| CAARS:Inv:SV | Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale: Investigator-Rated: Screening Version |

| CAARS:SV | Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale: Screening Version |

| CAARS-O | Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale-Observer |

| CAARS-S:L | Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale Self-Report Long Form |

| CADDRA | Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance |

| CalCAP | California Computerized Assessment Package |

| CCQ-GEN | Cocaine Craving Questionnaire–General |

| CD | Conduct Disorder |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impression |

| CPT3 | Conners’ Continuous Performance Test, 3rd Edition |

| C-SSRS | Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale |

| CUD | Cocaine Use Disorder |

| DBRS | Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale |

| DESR | Deficient Emotional Self-Regulation |

| ED | Emotional Dysregulation |

| EI | Emotional Impulsivity |

| FTND | Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence |

| GAD | Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

| GAF | Global Assessment of Functioning |

| GWB | General Well-Being Schedule |

| HAM-A | Hamilton Anxiety Scale |

| HAM-D | Hamilton Depression Scale |

| IGT | Iowa Gambling Task |

| LDX | Lisdexamfetamine |

| LSAS | Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MCG | Medical College of Georgia Paragraph Memory Test |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MNWS | Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Symptoms |

| MPH | Methylphenidate |

| OCD | Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder |

| OCDS | Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale |

| ODD | Oppositional Defiant Disorder |

| OQ45 | Outcome Questionnaire-45 |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study Design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| Q-LES-Q | Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| QOLIE-89 | Quality of Life in Epilepsy-89 |

| RAB | Risk Assessment Battery |

| SAD | Social Anxiety Disorder |

| SAS | Social Adjustment Scale–Self-Report |

| SCL-90-R | Symptom Checklist-90–Revised |

| SCWT | Stroop Color–Word Test |

| SDMT | Symbol Digit Modalities Test |

| SDS | Sheehan Disability Scale |

| SSC | Stimulant Side Effect Checklist |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| SUQ | Substance Use Questionnaire |

| TADDS | Targeted Attention Deficit Disorder Symptom Scale |

| TLFB | Time-Line Follow-Back self-report interview |

| TOVA | Test of Variables of Attention |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| WISPI-IV | Wisconsin Personality Disorders Inventory-IV |

| WRAADDS | Wender–Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale |

| YMRS | Young Mania Rating Scale |

References

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; 947p.

- Cristofani, C.; Sesso, G.; Cristofani, P.; Fantozzi, P.; Inguaggiato, E.; Muratori, P.; Narzisi, A.; Pfanner, C.; Pisano, S.; Polidori, L.; et al. The Role of Executive Functions in the Development of Empathy and Its Association with Externalizing Behaviors in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Other Psychiatric Comorbidities. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves, N.B.; Wells, E.L.; Soto, E.F.; Marsh, C.L.; Jaisle, E.M.; Harvey, T.K.; Kofler, M.J. Executive Functioning and Emotion Regulation in Children with and without ADHD. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022, 50, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milioni, A.L.; Chaim, T.M.; Cavallet, M.; de Oliveira, N.M.; Annes, M.; Dos Santos, B.; Louza, M.; da Silva, M.A.; Miguel, C.S.; Serpa, M.H.; et al. High IQ May “Mask” the Diagnosis of ADHD by Compensating for Deficits in Executive Functions in Treatment-Naïve Adults With ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2017, 21, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V.; Rostain, A.L.; Blader, J.; Busch, B.; Childress, A.C.; Connor, D.F.; Newcorn, J.H. Practitioner Review: Emotional dysregulation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—Implications for clinical recognition and intervention. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugi, G.; Hantouche, E.; Vannucchi, G. Diagnosis and Treatment of Cyclothymia: The “Primacy” of Temperament. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirrow, C.; Asherson, P. Emotional lability, comorbidity and impairment in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 147, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Adamo, N.; Ásgeirsdóttir, B.B.; Branney, P.; Beckett, M.; Colley, W.; Cubbin, S.; Deeley, Q.; Farrag, E.; Gudjonsson, G.; et al. Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leffa, D.T.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. ADHD in Children and Adults: Diagnosis and Prognosis. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 57, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone, S.V.; Biederman, J.; Mick, E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brancati, G.E.; De Rosa, U.; De Dominicis, F.; Petrucci, A.; Nannini, A.; Medda, P.; Schiavi, E.; Perugi, G. History of Childhood/Adolescence Referral to Speciality Care or Treatment in Adult Patients with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Mutual Relations with Clinical Presentation, Psychiatric Comorbidity and Emotional Dysregulation. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, V.; Migliarese, G.; Venturi, V.; Rossi, F.; Torriero, S.; Viganò, V.; Cerveri, G.; Mencacci, C. ADHD in adults: Clinical subtypes and associated characteristics. Riv. Psichiatr. 2019, 54, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Maremmani, I.; Spera, V.; Maiello, M.; Maremmani, A.G.I.; Perugi, G. Adult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder/Substance Use Disorder Dual Disorder Patients: A Dual Disorder Unit Point of View. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 57, 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, A.R.; Findling, R.L. Comorbidities in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A practical guide to diagnosis in primary care. Postgrad. Med. 2014, 126, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugi, G. Manuale di Clinica Psichiatrica; Amazon Italia Logistica S.r.l.: Torrazza Piemonte, Italy, 2023; 697p. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Barkley, R.; Biederman, J.; Conners, C.K.; Demler, O.; Faraone, S.V.; Greenhill, L.L.; Howes, M.J.; Secnik, K.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, P.; Nibbio, G.; Rosa, J.; Tamussi, E.; Turrina, C.; Sacchetti, E.; Vita, A. Adult ADHD: Prevalence and Clinical Correlates in a Sample of Italian Psychiatric Outpatients. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, S.V.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Brikell, I.; Cortese, S.; Hartman, C.A.; Hollis, C.; Newcorn, J.H.; Philipsen, A.; Polanczyk, G.V.; Rubia, K.; et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; Woo, Y.S.; Wang, S.M.; Lim, H.K.; Bahk, W.M. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in adult ADHD compared with non-ADHD populations: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, A.; Ayan, T.; Ince Guliyev, E.; Erbilgin, S.; Deveci, E. ADHD and Anxiety Disorder Comorbidity in Children and Adults: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Challenges. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2022, 24, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, V.; Ribuoli, E.; Servasi, M.; Orsolini, L.; Volpe, U. ADHD and Bipolar Disorder in Adulthood: Clinical and Treatment Implications. Medicina 2021, 57, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, S.J.; Bejerot, S.; Blackwell, A.; Caci, H.; Casas-Brugué, M.; Carpentier, P.J.; Edvinsson, D.; Fayyad, J.; Foeken, K.; Fitzgerald, M.; et al. European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, M.J.; Cortese, S. Current Pharmacological Treatments for ADHD. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 57, 19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarova, V.A.; Sokolov, A.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Tarasov, V.V.; Schiöth, H.B. Treatment of ADHD: Drugs, psychological therapies, devices, complementary and alternative methods as well as the trends in clinical trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1066988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otasowie, J.; Castells, X.; Ehimare, U.P.; Smith, C.H. Tricyclic antidepressants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, Cd006997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilens, T.E.; Prince, J.B.; Spencer, T.; Van Patten, S.L.; Doyle, R.; Girard, K.; Hammerness, P.; Goldman, S.; Brown, S.; Biederman, J. An open trial of bupropion for the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Marchant, B.K.; Strong, R.E.; Hedges, D.W.; Adler, L.; Spencer, T.J.; West, S.A.; Soni, P. Emotional Dysregulation in Adult ADHD and Response to Atomoxetine. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, T.; Biederman, J.; Wilens, T.; Doyle, R.; Surman, C.; Prince, J.; Mick, E.; Aleardi, M.; Herzig, K.; Faraone, S. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, L.A.; Liebowitz, M.; Kronenberger, W.; Qiao, M.; Rubin, R.; Hollandbeck, M.; Deldar, A.; Durell, T. Atomoxetine treatment in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbid social anxiety disorder. Depress. Anxiety 2009, 26, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rösler, M.; Retz, W.; Fischer, R.; Ose, C.; Alm, B.; Deckert, J.; Philpsen, A.; Herpertz, S.; Ammer, R. Twenty-four-week treatment with extended release methylphenidate improves emotional symptoms in adult ADHD. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 11, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Mick, E.; Spencer, T.; Surman, C.; Faraone, S.V. Is response to OROS-methylphenidate treatment moderated by treatment with antidepressants or psychiatric comorbidity? A secondary analysis from a large randomized double blind study of adults with ADHD. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012, 18, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.; Violato, C. Adjunctive atomoxetine to SSRIs or SNRIs in the treatment of adult ADHD patients with comorbid partially responsive generalized anxiety (GA): An open-label study. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2011, 3, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Alsuwaidan, M.; Soczynska, J.K.; Szpindel, I.; Bilkey, T.S.; Almagor, D.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Powell, A.M.; Cha, D.S.; Gallaugher, L.A.; et al. The effect of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate on body weight, metabolic parameters, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptomatology in adults with bipolar I/II disorder. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2013, 28, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, A.; Gvirts, H.Z.; Strouse, K.; Mayseless, N.; Gelbard, H.; Lewis, Y.D.; Barnea, Y.; Feffer, K.; Shamay-Tsoory, S.G.; Bloch, Y. A possible effect of methylphenidate on state anxiety: A single dose, placebo controlled, crossover study in a control group. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 241, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reekum, R.; Links, P.S. N of 1 study: Methylphenidate in a patient with borderline personality disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 1994, 39, 186–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gift, T.E.; Reimherr, F.W.; Marchant, B.K.; Steans, T.A.; Wender, P.H. Personality Disorder in Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Attrition and Change During Long-term Treatment. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2016, 204, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvirts, H.Z.; Lewis, Y.D.; Dvora, S.; Feffer, K.; Nitzan, U.; Carmel, Z.; Levkovitz, Y.; Maoz, H. The effect of methylphenidate on decision making in patients with borderline personality disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 33, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, F.R.; Evans, S.M.; McDowell, D.M.; Brooks, D.J.; Nunes, E. Bupropion treatment for cocaine abuse and adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Addict. Dis. 2002, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, F.R.; Evans, S.M.; McDowell, D.M.; Kleber, H.D. Methylphenidate treatment for cocaine abusers with adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A pilot study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somoza, E.C.; Winhusen, T.M.; Bridge, T.P.; Rotrosen, J.P.; Vanderburg, D.G.; Harrer, J.M.; Mezinskis, J.P.; Montgomery, M.A.; Ciraulo, D.A.; Wulsin, L.R.; et al. An open-label pilot study of methylphenidate in the treatment of cocaine dependent patients with adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Addict. Dis. 2004, 23, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstenius, M.; Jayaram-Lindström, N.; Beck, O.; Franck, J. Sustained release methylphenidate for the treatment of ADHD in amphetamine abusers: A pilot study. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2010, 108, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilens, T.E.; Adler, L.A.; Tanaka, Y.; Xiao, F.; D’Souza, D.N.; Gutkin, S.W.; Upadhyaya, H.P. Correlates of alcohol use in adults with ADHD and comorbid alcohol use disorders: Exploratory analysis of a placebo-controlled trial of atomoxetine. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2011, 27, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstenius, M.; Jayaram-Lindström, N.; Guterstam, J.; Beck, O.; Philips, B.; Franck, J. Methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and drug relapse in criminal offenders with substance dependence: A 24-week randomized placebo-controlled trial. Addiction 2014, 109, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.X.; Covey, L.S.; Hu, M.C.; Levin, F.R.; Nunes, E.V.; Winhusen, T.M. Toward personalized smoking-cessation treatment: Using a predictive modeling approach to guide decisions regarding stimulant medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in smokers. Am. J. Addict. 2015, 24, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winhusen, T.M.; Somoza, E.C.; Brigham, G.S.; Liu, D.S.; Green, C.A.; Covey, L.S.; Croghan, I.T.; Adler, L.A.; Weiss, R.D.; Leimberger, J.D. Impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatment on smoking cessation intervention in ADHD smokers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, M.E.; Herin, D.V.; Specker, S.; Babb, D.; Levin, F.R.; Grabowski, J. Pilot study of the effects of lisdexamfetamine on cocaine use: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 153, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Marchant, B.K.; Olsen, J.L.; Wender, P.H.; Robison, R.J. Oppositional defiant disorder in adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2013, 17, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, A.J.; Kahn, D.A.; Carpenter, D.; Docherty, J.P.; Donovan, S.L. The Expert Consensus Guidelines for treating depression in bipolar disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59 (Suppl. 4), 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.M. Strategies for managing depression complicated by bipolar disorder, suicidal ideation, or psychotic features. J. Am. Board. Fam. Pract. 1996, 9, 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Haykal, R.F.; Akiskal, H.S. Bupropion as a promising approach to rapid cycling bipolar II patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1990, 51, 450–455. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, G.S.; Lafer, B.; Stoll, A.L.; Banov, M.; Thibault, A.B.; Tohen, M.; Rosenbaum, J.F. A double-blind trial of bupropion versus desipramine for bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 55, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Retz, W.; Stieglitz, R.D.; Corbisiero, S.; Retz-Junginger, P.; Rösler, M. Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD: What is the empirical evidence? Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2012, 12, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A. Emotional dysregulation is a core component of ADHD. In Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Roesler, M.; Marchant, B.K.; Gift, T.E.; Retz, W.; Philipp-Wiegmann, F.; Reimherr, M.L. Types of Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Replication Analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 21798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimherr, F.W.; Marchant, B.K.; Gift, T.E.; Steans, T.A.; Wender, P.H. Types of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Baseline characteristics, initial response, and long-term response to treatment with methylphenidate. Atten. Defic. Hyperact. Disord. 2015, 7, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, P.; Stringaris, A.; Nigg, J.; Leibenluft, E. Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Pallucchini, A.; Rizzato, S.; Pinzone, V.; De Rossi, P. Current and emerging pharmacotherapy for the treatment of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 20, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, Ş.; Fıstıkcı, N.; Keyvan, A.; Bilici, M.; Çalışkan, M. ADHD in adult psychiatric outpatients: Prevalence and comorbidity. Turk Psikiyatr. Derg. 2014, 25, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Harpold, T.; Biederman, J.; Gignac, M.; Hammerness, P.; Surman, C.; Potter, A.; Mick, E. Is oppositional defiant disorder a meaningful diagnosis in adults? Results from a large sample of adults with ADHD. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2007, 195, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederman, J.; Spencer, T. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a noradrenergic disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, T.; Biederman, J.; Wilens, T.; Harding, M.; O’Donnell, D.; Griffin, S. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder across the life cycle. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 1996, 35, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zametkin, A.J.; Liotta, W. The neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59 (Suppl. 7), 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascher, J.A.; Cole, J.O.; Colin, J.N.; Feighner, J.P.; Ferris, R.M.; Fibiger, H.C.; Golden, R.N.; Martin, P.; Potter, W.Z.; Richelson, E.; et al. Bupropion: A review of its mechanism of antidepressant activity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1995, 56, 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Grizenko, N.; Bhat, V.; Sengupta, S.; Polotskaia, A.; Joober, R. Relation between therapeutic response and side effects induced by methylphenidate as observed by parents and teachers of children with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, R.O. Dopamine dysfunction in borderline personality disorder: A hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haaland, V.; Landrø, N.I. Decision making as measured with the Iowa Gambling Task in patients with borderline personality disorder. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2007, 13, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurex, L.; Zaboli, G.; Wiens, S.; ÅSberg, M.; Leopardi, R.; ÖHman, A. Emotionally controlled decision-making and a gene variant related to serotonin synthesis in women with borderline personality disorder. Scand. J. Psychol. 2009, 50, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robison, R.J.; Reimherr, F.W.; Gale, P.D.; Marchant, B.K.; Williams, E.D.; Soni, P.; Halls, C.; Stromg, R.E. Personality disorders in ADHD Part 2: The effect of symptoms of personality disorder on response to treatment with OROS methylphenidate in adults with ADHD. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 22, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, J.L.; Reimherr, F.W.; Marchant, B.K.; Wender, P.H.; Robison, R.J. The effect of personality disorder symptoms on response to treatment with methylphenidate transdermal system in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012, 14, 26293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asherson, P.J.; Johansson, L.; Holland, R.; Bedding, M.; Forrester, A.; Giannulli, L.; Ginsberg, Y.; Howitt, S.; Kretzchmar, I.; Lawrie, S.M.; et al. Randomised controlled trial of the short-term effects of osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate on symptoms and behavioural outcomes in young male prisoners with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: CIAO-II study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2023, 222, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, M.M.; Gremillion, M.; Roberts, B.; von Eye, A.; Nigg, J.T. The structure of childhood disruptive behaviors. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 22, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author and Year | Study Design | Subjects and Diagnoses | Pharmacotherapy | Comparisons | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilens, T. E., 2003 [27] | Open-label, prospective, 6-week | 36 ADHD and BD | Bupropion (up to 400 mg/day) | CGI, ARS, HAM-D, BDI, HAM-A, YMRS | Reduction in manic and depressive symptoms. Mild reduction in anxiety. |

| Reimherr, F. W., 2005 [28] | Retrospective | 536 ADHD and affective and/or anxiety disorders | ATX (up to 120 mg/day) | CGI, CAARS, WRAADDS, HAM-D, HAM-A, SDS | ↑ Emotional regulation in ATX vs. placebo. No significant changes in depression or anxiety between ATX and placebo. |

| Spencer, T., 2005 [29] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, 6-week | 146 ADHD and affective and/or anxiety disorders | MPH (n = 104) (mean 82 ± 22 mg/day) Placebo (n = 42) | CGI, AISRS, HAM-D, BDI; HAM-A | No significant changes in depression or anxiety between MPH and placebo. |

| Adler, L. A., 2009 [30] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, multi-center, 16-week | 442 ADHD and social anxiety and/or GAD | ATX (n = 224) (up to 100 mg/day) Placebo (n = 218) | LSAS, CGI, CAARS:Inv:SV, SAS, STAI | ↑ ADHD and social anxiety symptoms in ATX vs. placebo. No significant changes in GAD between ATX and placebo. |

| Rösler, M., 2010 [31] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, multi-center, 24-week | 363 ADHD and affective, anxiety, and/or personality disorders | MPH (n = 241) (up to 60 mg/day) Placebo (n = 118) | WRAADDS, CAARS-S:L, SCL-90-R | ↑ Emotional regulation in MPH vs. placebo. No significant changes in depression or anxiety between MPH and placebo. |

| Biederman, J., 2012 [32] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, 6-week | 227 ADHD and affective, anxiety disorders, and/or SUD | MPH (n = 112) (mean 78.4 ± 31.7 mg/day) Placebo (n = 115) | CGI, AISRS, HAM-D, HAM-A, GAF | No significant changes in depression, anxiety, or SUD between MPH and placebo. |

| Gabriel, A., 2011 [33] | Open-label, cross-sectional, 12-week | 29 ADHD and GAD | ATX (up to 80 mg/day) | CGI, ASRS, HAM-A, SDS, CADDRA side effect scale | ↑ Anxiety symptoms. Cognitive anxiety symptoms are predominant over the somatic anxiety symptoms. |

| McIntyre, R. S., 2013 [34] | Open-label, prospective, flexible-dose, 4-week | 40 ADHD and BD | LDX (up to 70 mg/day) | CGI, YMRS, MADRS, C-SSRS, ADHD-RS, CAARS, Q-LES-Q, AAQoL | Less MADRS total score. No induction of hypo/manic or psychotic symptomatology. |

| Segev, A., 2016 [35] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, random block order crossover, two sessions 2 weeks apart | 36 ADHD and anxiety disorders | MPH (20 mg/session) Placebo | STAI, VAS | ↑ state and trait-anxiety in “high initial state-anxiety” group with MPH. ↓ state-anxiety in “low initial state-anxiety” group with MPH. No changes with placebo. |

| First Author and Year | Study Design | Subjects and Diagnoses | Pharmacotherapy | Comparisons | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Reekum, R., 1994 [36] | N of 1, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 18-week | 1 ADHD and BPD | MPH (up to 40 mg/day) Placebo | Symptoms, attention, vigilance, and impulse inhibition assessments, urine test | Significant decrease of BPD symptomatology in MPH vs. placebo. |

| Gift, T. E., 2016 [37] | Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose, crossover, two 4-week and subsequently 6-month open-label phase | 115 ADHD and personality disorders | MPH Placebo | CGI, WRAADS, WISPI-IV | ↑ personality disorder’s symptoms in end-point vs. baseline. Narcissistic and Borderline D. showed improvement in more items of the WISPI-IV than the other disorders. Measures were not correlated with changes in ADHD. |

| Gvirts, H. Z., 2018 [38] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, two session 1–2 weeks apart | 20 ADHD and BPD | MPH (20–30 mg/session) Placebo | TOVA, forward and backward digit-span tasks, IGT | Lower scores of inattention symptoms were associated with greater improvement in decision-making in MPH vs. placebo |

| First Author and Year | Study Design | Subjects and Diagnoses | Pharmacotherapy | Comparisons | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levin, F. R., 2002 [39] (including Levin, F. R., 1998 [40]) | Cross-sectional, 12-week | 10 + 10 ADHD and CUD | Bupropion (n = 10) (up to 400 mg/day) MPH (n = 10) (up to 80 mg/day) | ARS, TADDS, ASI, urine test | ↑ ADHD symptoms, cocaine-free weeks, and less cocaine craving in Bupropion and MPH, the efficacy is comparable. |

| Somoza, E. C., 2004 [41] | Open-label, multi-center, 10-week | 41 ADHD and CUD | MPH (up to 60 mg/day) Compliant (n = 19) Non-compliant (n = 22) | CGI, ASI, SUQ, BSCS, CCQ-GEN, RAB, urine test, CalCAP | Low level of cocaine use in compliant vs. non-compliant. |

| Konstenius, M., 2010 [42] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-week | 24 ADHD and amphetamine dependence | MPH (n = 12) (up to 72 mg/day) Placebo (n = 12) | CAARS:SV, CAARS-O, ASI, TLFB, Tiffany Craving scale, BDI-II, BAI, Stroop Test, urine test | No significant changes in relapse rate, time to relapse or cumulative abstinence rate between MPH and placebo. |

| Wilens, T. E., 2011 [43] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center, 12-week | 147 ADHD and alcohol abuse | ATX (n = 72) (up to 100 mg/day) Placebo (n = 75) | AISRS, ASRS, Timeline Followback method, OCDS | Reduction in alcohol craving correlated with improvements in ADHD symptoms |

| Konstenius, M., 2014 [44] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, 24-week | 54 ADHD and amphetamine dependence | MPH (n = 27) (up to 180 mg/day) Placebo (n = 27) | CGI, CAARS:SV, OQ45, urine test | Shorter time to first positive urine in placebo vs. MPH. Significantly decrease of craving in MPH vs. placebo. |

| Luo, S. X., 2015 [45] (including Winhusen, T. M., 2010 [46]) | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, multi-center, 11-week | 255 ADHD and smokers | MPH (n = 127) (up to 72 mg/day) Placebo (n = 128) | Expired carbon monoxide, MNWS, FTND, BDI, ADHD-RS | No significant improvement in smoking cessation in MPH vs. placebo. MPH may promote prolonged abstinence for more severe ADHD (ADHD-RS > 35), conversely it may be counterproductive. |

| Mooney, M. E., 2015 [47] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-design, 14-week | 43 ADHD and CUD | LDX (n = 22) (up to 70 mg/day) Placebo (n = 21) | BDI-II, ASI, urine test | Partial evidence of reduction in cocaine use in LDX vs. placebo. Less cocaine craving in LDX vs. placebo. |

| First Author and Year | Study Design | Subjects and Diagnoses | Pharmacotherapy | Comparisons | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reimherr, F. W., 2013 [48] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, two 4-week | 36 ADHD and adult ODD 23 ADHD and child ODD 27 ADHD non-ODD | MPH (up to 30 mg/day) Placebo | CGI, WRAADS, CAARS, DBRS | ↑ ODD symptomatology in ADHD and ODD group, highly correlated with changes in ADHD symptoms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tripodi, B.; Carbone, M.G.; Matarese, I.; Rizzato, R.; Della Rocca, F.; De Dominicis, F.; Callegari, C. Effectiveness of Pharmacological Treatments for Adult ADHD on Psychiatric Comorbidity: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248848

Tripodi B, Carbone MG, Matarese I, Rizzato R, Della Rocca F, De Dominicis F, Callegari C. Effectiveness of Pharmacological Treatments for Adult ADHD on Psychiatric Comorbidity: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248848

Chicago/Turabian StyleTripodi, Beniamino, Manuel Glauco Carbone, Irene Matarese, Roberta Rizzato, Filippo Della Rocca, Francesco De Dominicis, and Camilla Callegari. 2025. "Effectiveness of Pharmacological Treatments for Adult ADHD on Psychiatric Comorbidity: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248848

APA StyleTripodi, B., Carbone, M. G., Matarese, I., Rizzato, R., Della Rocca, F., De Dominicis, F., & Callegari, C. (2025). Effectiveness of Pharmacological Treatments for Adult ADHD on Psychiatric Comorbidity: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8848. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248848