The Impact of Surgical Approach on Mid-Term Clinical Outcomes Following Hemiarthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Postero-Lateral Versus Direct Lateral Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

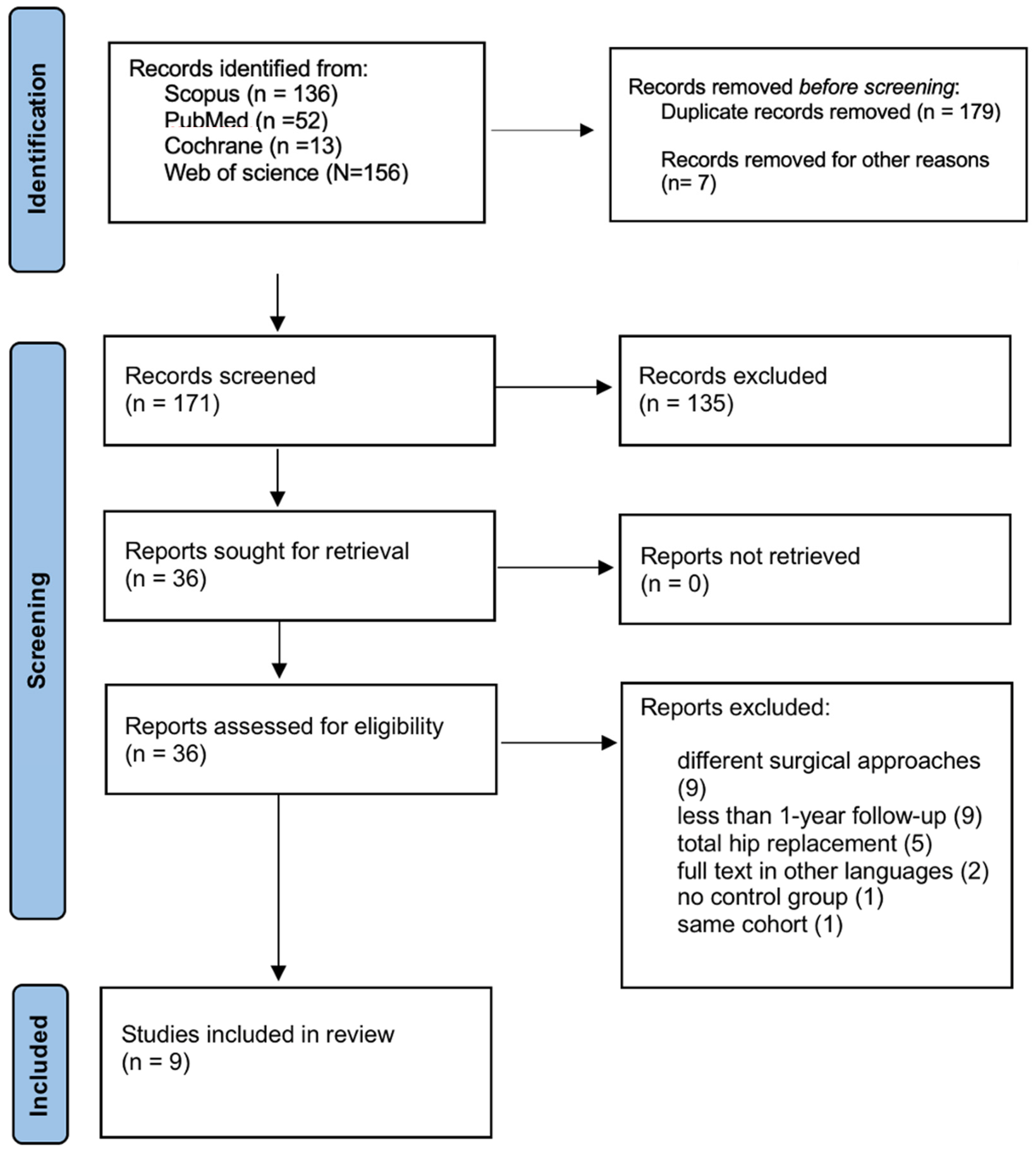

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- P (Population): Adults with femoral neck fractures (FNFs) treated with hemiarthroplasty (HA). Only acute, traumatic FNFs were eligible. We excluded patients with pathological fractures, bilateral procedures, revision HA, or non-traumatic indications

- I (Intervention): HA performed via a PL surgical approach.

- C (Comparison): HA performed via a DL surgical approach.

- O (Outcomes): The primary outcomes of interest include operative time, incidence of dislocations, infections, perioperative fractures and reoperations. Secondary outcomes include PROs, specifically quality of life (EQ-5D scores), pain levels (VAS scores), and overall patient satisfaction. Studies must report at least one of these specified outcomes.

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

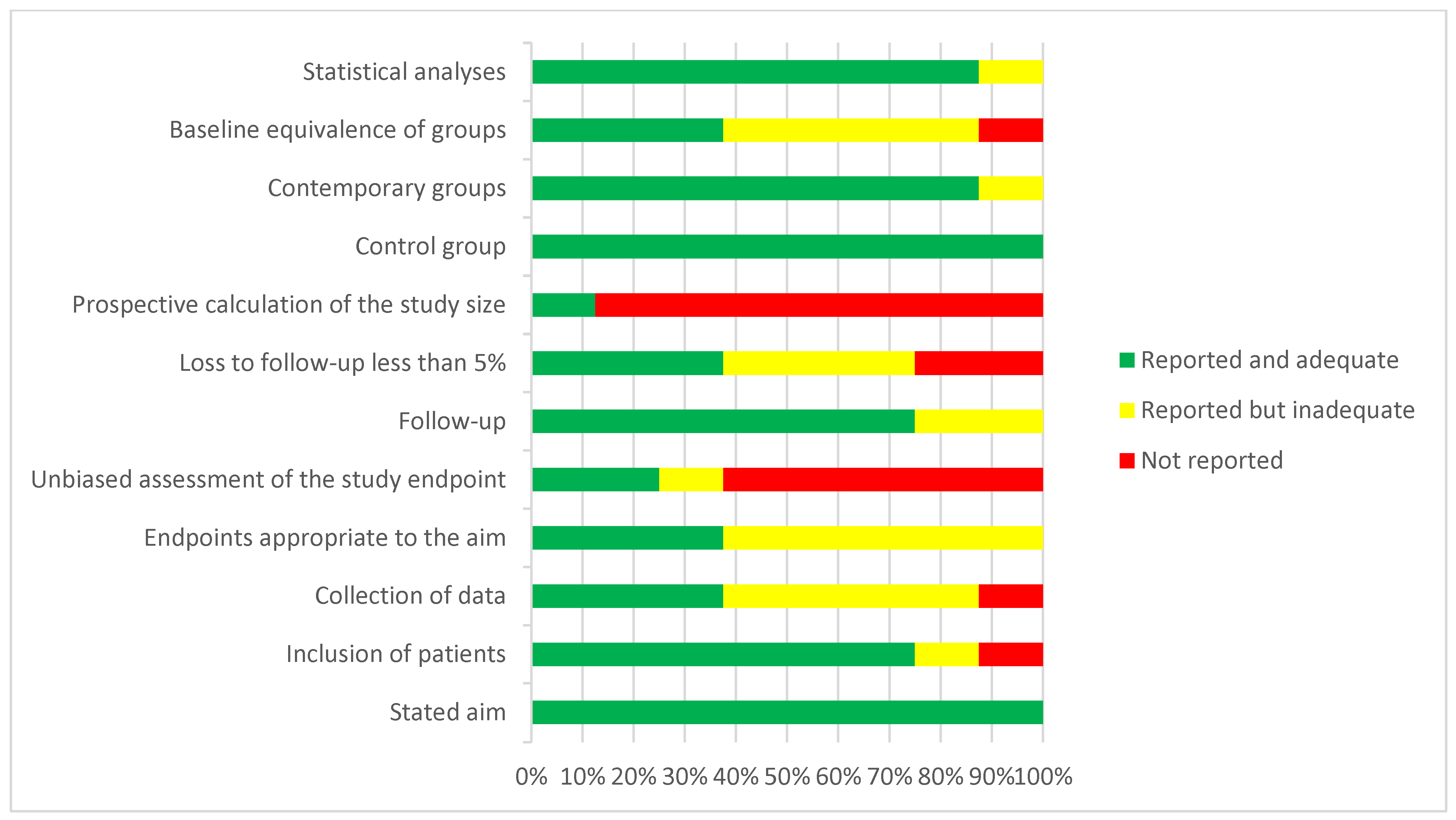

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.4. Operative Outcomes

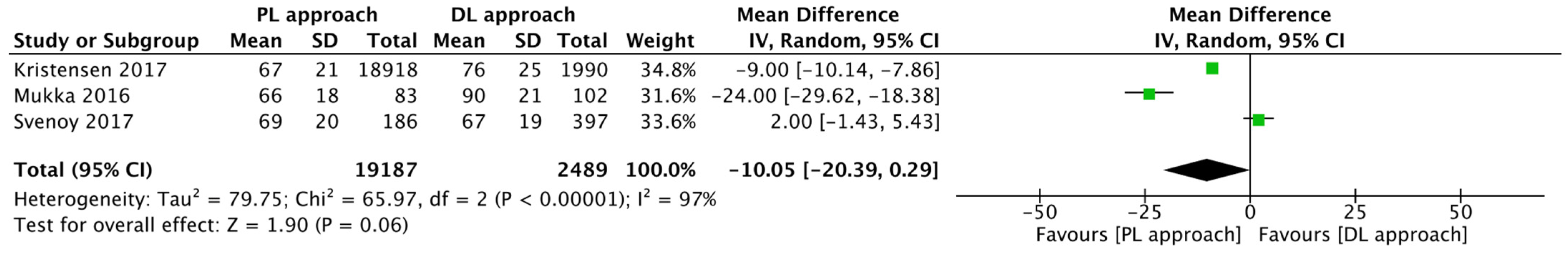

Operative Time

3.5. Post-Operative Complications

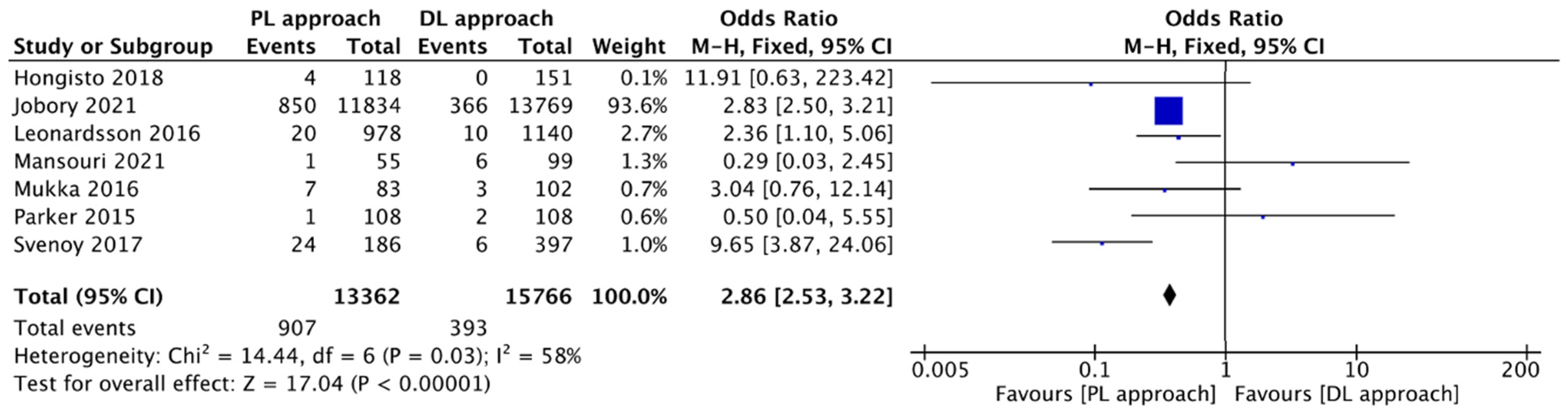

3.5.1. Dislocations

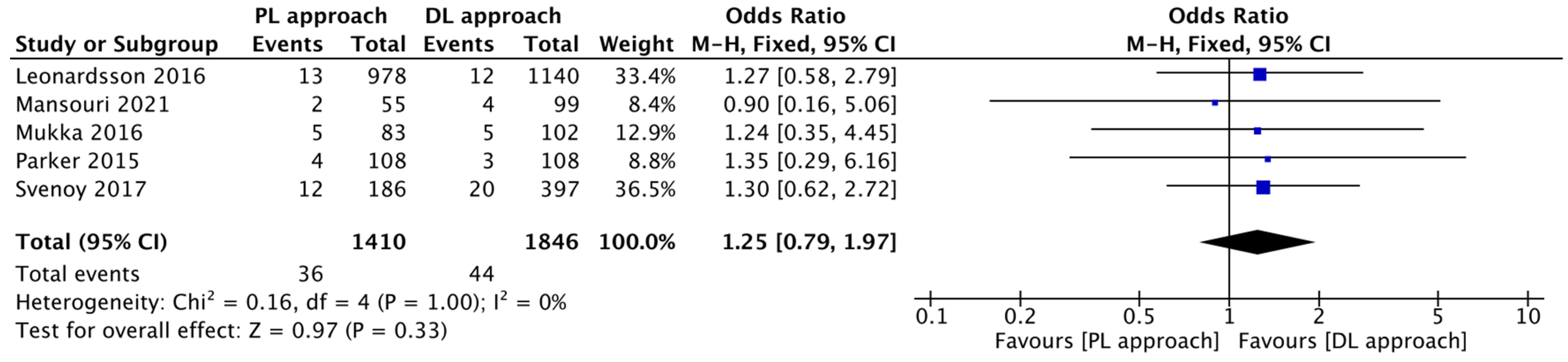

3.5.2. Infections

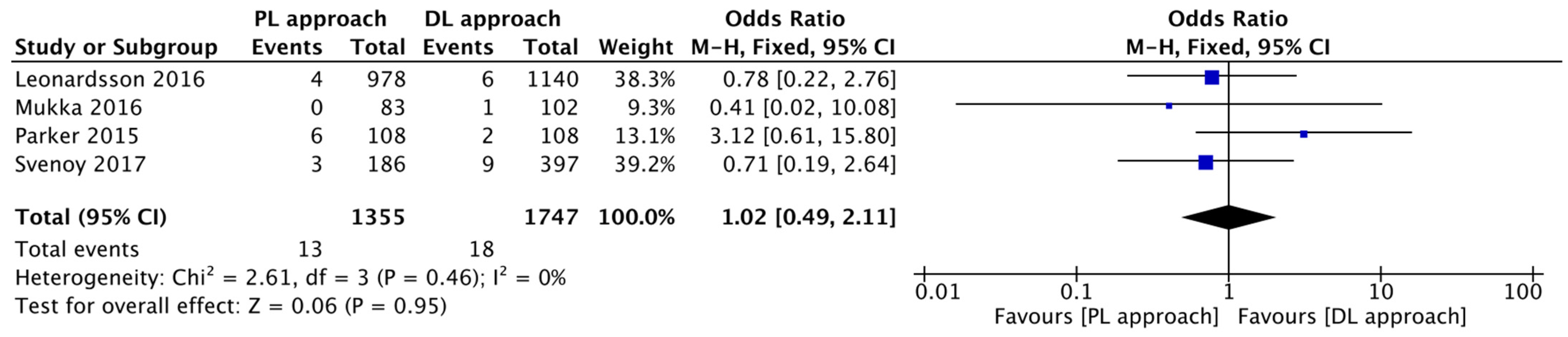

3.6. Perioperative Fractures

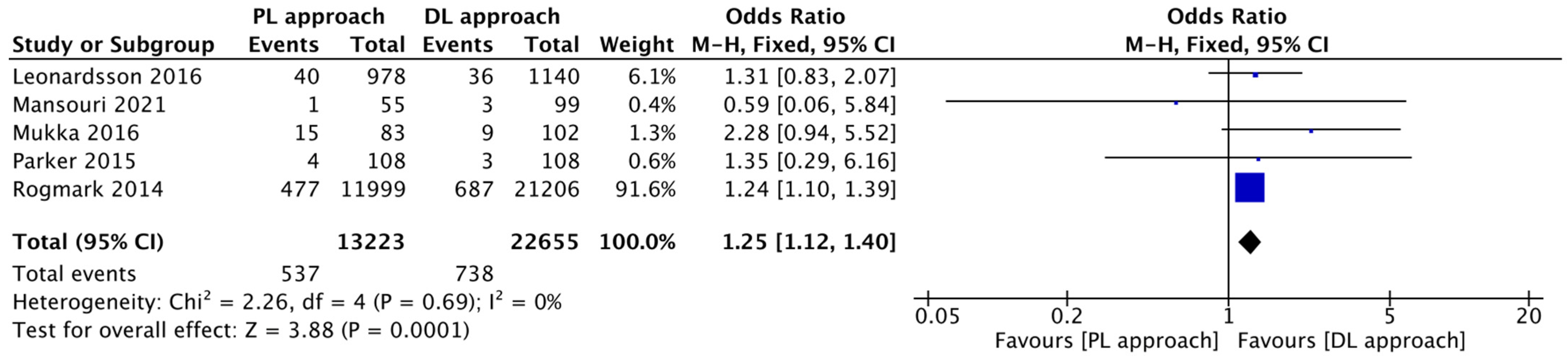

3.7. Reoperations

3.8. Patient-Reported Outcomes

3.8.1. EQ-5D

3.8.2. Pain

3.8.3. Satisfaction

3.9. Other Notable Findings

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, J.-N.; Zhang, C.-G.; Li, B.-H.; Zhan, S.-Y.; Wang, S.-F.; Song, C.-L. Global burden of hip fracture: The Global Burden of Disease Study. Osteoporos. Int. 2024, 35, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogmark, C.; Leonardsson, O. Hip arthroplasty for the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. Bone Jt. J. 2016, 98-B, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, L.; Huiwen, W.; Shihao, D.; Fangyuan, W.; Juehua, J.; Jun, L. A comparison of different surgical approaches to hemiarthroplasty for the femoral neck fractures: A meta-analysis. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1049534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippini, M.; Bortoli, M.; Montanari, A.; Pace, A.; Di Prinzio, L.; Lonardo, G.; Parisi, S.C.; Persiani, V.; De Cristofaro, R.; Sambri, A.; et al. Does Surgical Approach Influence Complication Rate of Hip Hemiarthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures? A Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusho, C.; Hoskins, W.; Ghanem, E. A Comparison of Surgical Approaches for Hip Hemiarthroplasty Performed for the Treatment of Femoral Neck Fracture: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JBJS Rev. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tol, M.C.J.M.; Beers, L.W.A.H.v.; Willigenburg, N.W.; Gosens, T.; Heetveld, M.J.; Willems, H.C.; Bhandari, M.; Poolman, R.W. Posterolateral or direct lateral approach for hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fractures: A systematic review. HIP Int. 2021, 31, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullam, J.; Theodosi, P.G.; Charity, J.; Goodwin, V.A. A scoping review comparing two common surgical approaches to the hip for hemiarthroplasty. BMC Surg. 2019, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enocson, A.; Tidermark, J.; Törnkvist, H.; Lapidus, L.J. Dislocation of hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture: Better outcome after the anterolateral approach in a prospective cohort study on 739 consecutive hips. Acta Orthop. 2008, 79, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, T.B.; Vinje, T.; I Havelin, L.; Engesæter, L.B.; Gjertsen, J.-E. Posterior approach compared to direct lateral approach resulted in better patient-reported outcome after hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture. Acta Orthop. 2017, 88, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sijp, M.P.; van Delft, D.; Krijnen, P.; Niggebrugge, A.H.; Schipper, I.B. Surgical Approaches and Hemiarthroplasty Outcomes for Femoral Neck Fractures: A Meta-Analysis. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 1617–1627.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogmark, C.; Fenstad, A.M.; Leonardsson, O.; Engesæter, L.B.; Kärrholm, J.; Furnes, O.; Garellick, G.; Gjertsen, J.-E. Posterior approach and uncemented stems increases the risk of reoperation after hemiarthroplasties in elderly hip fracture patients. Acta Orthop. 2014, 85, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukka, S.; Mahmood, S.; Kadum, B.; Sköldenberg, O.; Sayed-Noor, A. Direct lateral vs posterolateral approach to hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2016, 102, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongisto, M.T.; Nuotio, M.S.; Luukkaala, T.; Väistö, O.; Pihlajamäki, H.K. Lateral and Posterior Approaches in Hemiarthroplasty. Scand. J. Surg. 2018, 107, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.J. Lateral versus posterior approach for insertion of hemiarthroplasties for hip fractures: A randomised trial of 216 patients. Injury 2015, 46, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardsson, O.; Rolfson, O.; Rogmark, C. The surgical approach for hemiarthroplasty does not influence patient-reported outcome: A national survey of 2118 patients with one-year follow-up. Bone Joint J. 2016, 98-B, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svenoy, S.; Westberg, M.; Figved, W.; Valland, H.; Brun, O.C.; Wangen, H.; Madsen, J.E.; Frihagen, F. Posterior versus lateral approach for hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture: Early complications in a prospective cohort of 583 patients. Injury 2017, 48, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri-Tehrani, M.M.; Yavari, P.; Pakdaman, M.; Eslami, S.; Nourian, S.M.A. Comparison of surgical complications following hip hemiarthroplasty between the posterolateral and lateral approaches. Int. J. Burns Trauma. 2021, 11, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jobory, A.; Kärrholm, J.; Hansson, S.; Åkesson, K.; Rogmark, C. Dislocation of hemiarthroplasty after hip fracture is common and the risk is increased with posterior approach: Result from a national cohort of 25,678 individuals in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2021, 92, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Design | Patients per Approach | Follow-Up (Months) | Age | Sex (%F) | Baseline Disparities Detected | Blinding of Outcome Assessment | Risk of Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parker 2015 [14] | RCT | PL DL | 108 108 | 12 | 84 | 92 | No significant differences. | Yes (Partial), Research nurse blinded for outcome assessment. | Study underpowered (early termination). Performance bias inherent. |

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | PS | PL DL | 83 101 | 12 | 84.4 | 70 | No significant differences. | Yes (Partial), Research nurse blinded for patient-reported outcomes (PROMs). | High risk of Selection Bias (surgeon’s preference). Partially mitigated by multivariate adjustment. |

| Svenoy et al., 2017 [16] | PS | PL DL | 186 397 | 12 | 82.8 | 74 | No significant differences in patient demographics. Source of patients (hospital) and surgical volume differed. | No. Outcome assessment (complication) based on chart review (unblinded). | High risk of Selection/Performance Bias. PL group from one hospital, DL group from three different hospitals. |

| Kristensen et al., 2017 [9] | RS | PL DL | 18,918 7900 | 12 | 83 | 73 | Posterior group had more uncemented prostheses and shorter surgery time. | Yes (Objective Data/Partial), PROMs collected susceptible to recall/non-response bias. Reoperation data is objective. | High risk of Selection Bias (observational registry data). |

| Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | RS | PL DL | 9781 140 | 12 | 85 | 74 | DL group had more unipolar implants and worse health (higher ASA class). | Yes (Partial), PROMs via questionnaire. Reoperation data is objective. | High risk of Selection Bias. Mitigated by multivariate adjustment. |

| Rogmark et al., 2014 [11] | RS | PL DL | 11,523 20,519 | 32.4 ± 20.4 | 84 | 72 | Implicit/Not reported. Implants/Approaches not balanced between cohorts. | Yes (Objective Data), Outcome is reoperation (objective, registry-based data). | High risk of Selection Bias (different approach/implants in different hospitals/countries). |

| Mansouri et al., 2021 [17] | RS | PL DL | 55 99 | 36.70 ± 16.64 36.46 ± 19.48 | 75.4 78 | 59 | No significant difference. | No. Outcome assessment relied on unblinded review and unblinded phone calls. | Retrospective study on small sample. High risk of Detection Bias (phone calls). High loss to follow-up. |

| Hongisto et al., 2018 [13] | RS | PL DL | 118 151 | 12 | 82.8 | 79 | Uncemented stems used more often in the DL group. | No (Implicit), Outcomes assessed by phone interview (unblinded) or via registry/charts. | High risk of Selection Bias (surgeon on duty selected approach). |

| Jobory et al., 2021 [18] | RS | PL DL | 11,384 13,769 | 12 | NR | 71 | Posterior approach was more common for bipolar HA. | Yes (Objective Data), Outcome is dislocation (closed reduction and reoperation) via cross-registry linkage (objective). | High risk of Selection Bias. Mitigated by extremely large sample and comprehensive adjustment. |

| Risk of Bias Domains | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1: Randomization Process | D2: Interventions | D3: Missing Outcome Data | D4: Measurement of the Outcome | D5: Selection of Reported | Overall Risk | ||

| Study | Parker 2015 [14] | Low Risk | Some Concerns | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Some Concerns |

| Study | Stated Aim | Inclusion of Patients | Collection of Data | Endpoints Appropriate to the Aim | Unbiased Assessment of the Study Endpoint | Follow-Up | Loss to Follow-Up Less Than 5% | Prospective Calculation of the Study Size | Control Group | Contemporary Groups | Baseline Equivalent of Groups | Statistical Analyses | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 |

| Svenoy et al., 2017 [16] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| Kristensen et al., 2017 [9] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| Rogmark et al., 2014 [11] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 13 |

| Mansouri et al., 2021 [17] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Hongisto et al., 2018 [13] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 17 |

| Jobory et al., 2021 [18] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Posterior Approach | Lateral Approach | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Mean | SD | Patients | Mean | SD | Patients | |

| Operative time | Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 66 | 18 | 83 | 90 | 21 | 101 |

| Kristensen et al., 2017 [9] | 67 | 21 | 18,918 | 76 | 25 | 1990 | |

| Svenoy et al., 2017 [16] | 69.2 | 20 | 186 | 66.9 | 19 | 397 | |

| Parker 2015 [14] | 54.0 | NR | 108 | 53.6 | NR | 108 | |

| Posterior Approach | Lateral Approach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Events | Patients | Events | Patients | |

| Dislocation | Parker 2015 [14] | 1 | 108 | 2 | 108 |

| Mansouri et al., 2021 [17] | 1 | 55 | 6 | 99 | |

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 7 | 83 | 3 | 102 | |

| Svenoy et al., 2017 [16] | 24 | 186 | 6 | 397 | |

| Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 20 | 978 | 10 | 1140 | |

| Hongisto et al., 2018 [13] | 4 | 118 | 0 | 151 | |

| Jobory et al., 2021 [18] | 850 | 11,834 | 366 | 13,769 | |

| Infection | Parker 2015 [14] | 4 | 108 | 3 | 108 |

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 5 | 83 | 5 | 102 | |

| Svenoy et al., 2017 [16] | 12 | 186 | 20 | 397 | |

| Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 13 | 978 | 12 | 1140 | |

| Mansouri et al., 2021 [17] | 2 | 55 | 4 | 99 | |

| Perioperative fractures | Parker 2015 [14] | 6 | 108 | 2 | 108 |

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 0 | 82 | 1 | 102 | |

| Svenoy et al., 2017 [16] | 3 | 186 | 8 | 397 | |

| Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 4 | 978 | 6 | 1140 | |

| Reoperation | Parker 2015 [14] | 4 | 108 | 3 | 108 |

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 15 | 83 | 9 | 102 | |

| Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 40 | 978 | 36 | 1140 | |

| Rogmark et al., 2014 [11] | 477 | 11,999 | 687 | 21,206 | |

| Mansouri et al., 2021 [17] | 1 | 55 | 3 | 99 | |

| Study | Scale Polarity | Posterior Approach | Lateral Approach | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 1.0 = Perfect Health <0.0 = Worse than Death | 0.52 ± 0.37 | 0.47 ± 0.37 |

| Kristensen et al., 2017 [9] | 1.0 = Perfect Health <0.0 = Worse than Death | 0.64 | 0.61 | |

| Pain | Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 0 = No Pain 100 = Worst Pain | 17 ± 19 | 19 ± 20 |

| Kristensen et al., 2017 [9] | 0 = No Pain 100 = Worst Pain | 17 | 20 | |

| Mukka et al., 2016 [12] | 0 = No Pain 100 = Worst Pain | 20 ± 17 | 21 ± 22 | |

| satisfaction | Leonardsson et al., 2016 [15] | 0 = Max. Satisfaction 100 = Min. Satisfaction | 22 ± 23 | 24 ± 24 |

| Kristensen et al., 2017 [9] | 0 = Max. Satisfaction 100 = Min. Satisfaction | 21 | 25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcello, G.; Parisi, F.R.; Diaz Balzani, L.A.; Del Monaco, A.; Zappalà, E.; Papalia, G.F.; Capperucci, C.; Albo, E.; Ferrini, A.; Zampogna, B.; et al. The Impact of Surgical Approach on Mid-Term Clinical Outcomes Following Hemiarthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Postero-Lateral Versus Direct Lateral Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248846

Marcello G, Parisi FR, Diaz Balzani LA, Del Monaco A, Zappalà E, Papalia GF, Capperucci C, Albo E, Ferrini A, Zampogna B, et al. The Impact of Surgical Approach on Mid-Term Clinical Outcomes Following Hemiarthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Postero-Lateral Versus Direct Lateral Approaches. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248846

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcello, Gianmarco, Francesco Rosario Parisi, Lorenzo Alirio Diaz Balzani, Alessandro Del Monaco, Emanuele Zappalà, Giuseppe Francesco Papalia, Chiara Capperucci, Erika Albo, Augusto Ferrini, Biagio Zampogna, and et al. 2025. "The Impact of Surgical Approach on Mid-Term Clinical Outcomes Following Hemiarthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Postero-Lateral Versus Direct Lateral Approaches" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248846

APA StyleMarcello, G., Parisi, F. R., Diaz Balzani, L. A., Del Monaco, A., Zappalà, E., Papalia, G. F., Capperucci, C., Albo, E., Ferrini, A., Zampogna, B., & Papalia, R. (2025). The Impact of Surgical Approach on Mid-Term Clinical Outcomes Following Hemiarthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Postero-Lateral Versus Direct Lateral Approaches. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248846