Testing the Efficacy of Eptinezumab 100 mg in the Early Prevention of Chronic Migraine over Weeks 1 to 4: Prospective Real-World Data from the GRASP Study Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Efficacy Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

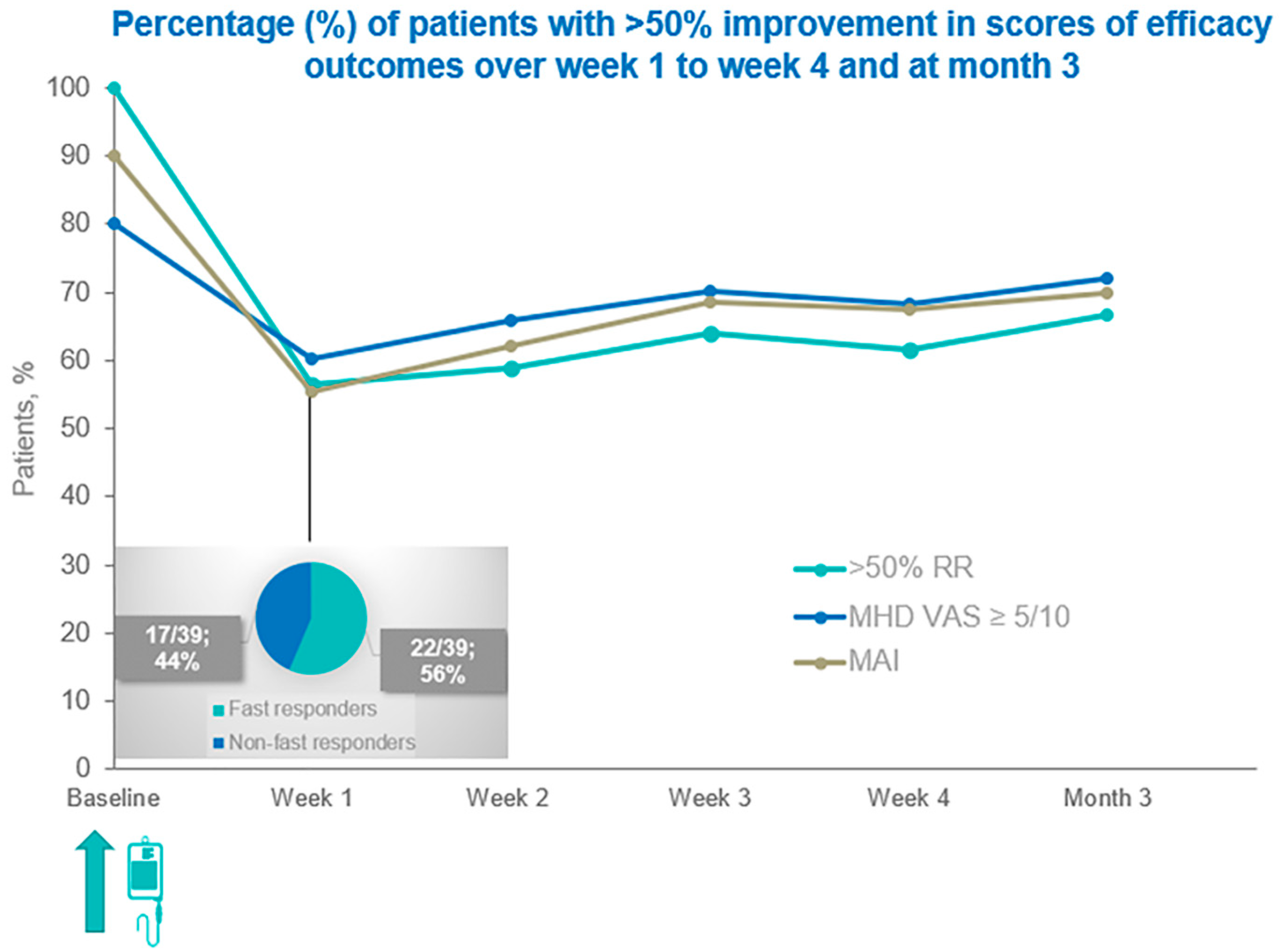

3.1. Changes Relating to Patients’ Primary and Co-Primary Clinical Outcomes over Time

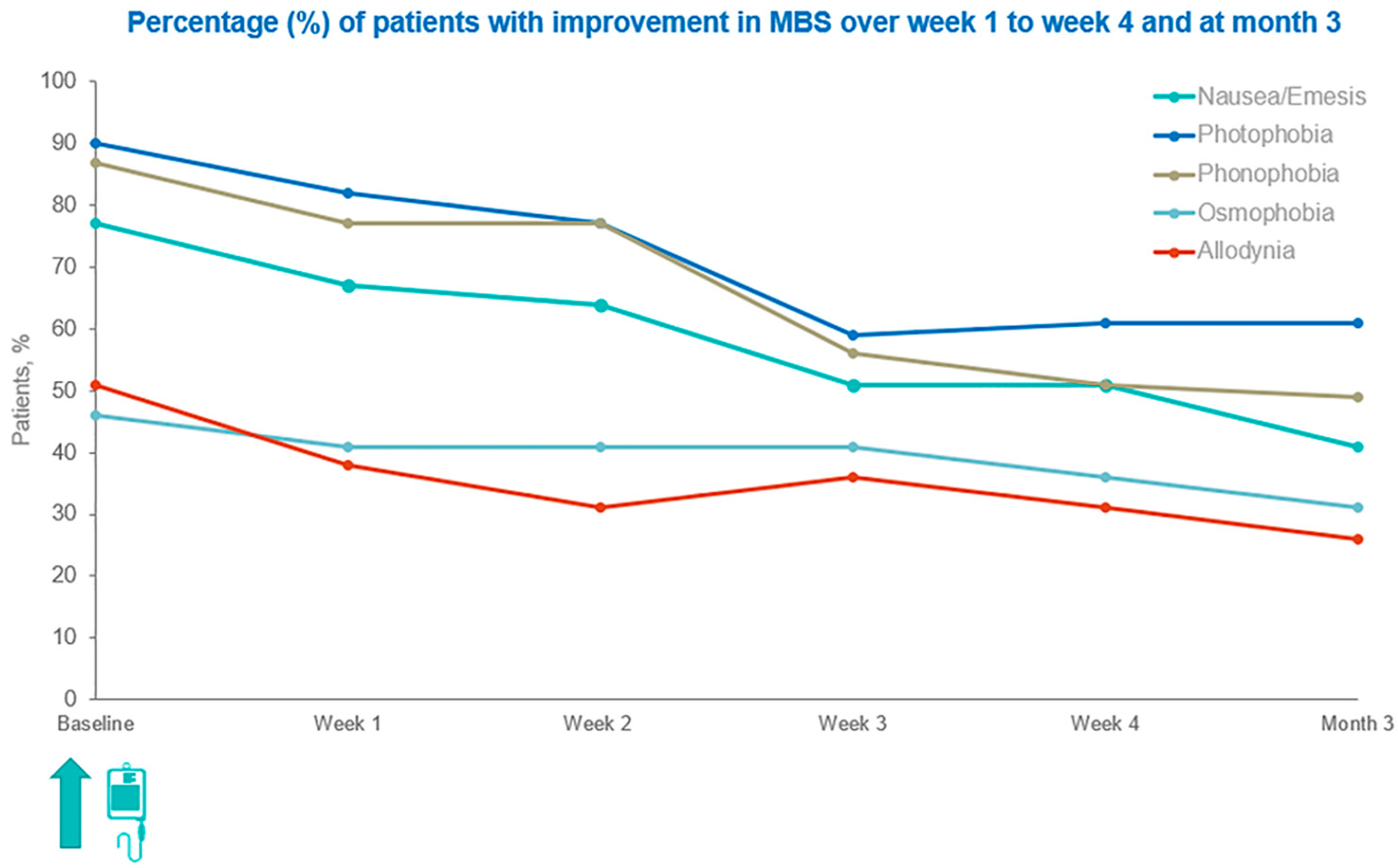

3.2. Changes in the Occurrence of Patients’ MBS over Time

3.3. Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) at Week 4, Post-Eptinezumab

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lipton, R.B.; Nicholson, R.A.; Reed, M.L.; Araujo, A.B.; Jaffe, D.H.; Faries, D.E.; Buse, D.C.; Shapiro, R.E.; Ashina, S.; Cambron--Mellott, M.J.; et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: Results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache 2022, 62, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.J.; Terwindt, G.M.; Katsarava, Z.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Gantenbein, A.R.; Roche, S.L.; Dell’aGnello, G.; Tassorelli, C. Migraine-attributed burden, impact and disability, and migraine-impacted quality of life: Expert consensus on definitions from a Delphi process. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.M.; Serrano, D.; Buse, D.C.; Reed, M.L.; Marske, V.; Fanning, K.M.; Lipton, R.B. The impact of chronic migraine: The Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia 2015, 35, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Buse, D.C.; Nahas, S.J.; Tietjen, G.E.; Martin, V.T.; Löf, E.; Brevig, T.; Cady, R.; Diener, H.-C. Risk factors for migraine disease progression: A narrative review for a patient-centered approach. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 5692–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Dermitzakis, E.V.; Rikos, D.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Soldatos, P.; Litsardopoulos, P.; Vikelis, M. Effects of OnabotulinumtoxinA on Allodynia and Interictal Burden of Patients with Chronic Migraine. Toxins 2024, 16, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungoven, T.J.; Henderson, L.A.; Meylakh, N. Chronic Migraine Pathophysiology and Treatment: A Review of Current Perspectives. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 705276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, S.; Shiina, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Hirata, K. Central Sensitization in Migraine: A Narrative Review. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Dermitzakis, E.V.; Chondrogianni, M.; Foska, A.; Rikos, D.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Soldatos, P.; Litsardopoulos, P.; Vikelis, M. OnabotulinumtoxinA to Prevent Chronic Migraine with Comorbid Bruxism: Real-World Data from the GRASP Study Group. Toxins 2025, 17, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, D.C.; Armand, C.E.; Charleston, L., 4th; Reed, M.L.; Fanning, K.M.; Adams, A.M.; Lipton, R.B. Barriers to care in episodic and chronic migraine: Results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes Study. Headache 2021, 61, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eltrafi, A.; Shrestha, S.; Ahmed, A.; Mistry, H.; Paudyal, V.; Khanal, S. Economic burden of chronic migraine in OECD countries: A systematic review. Health Econ. Rev. 2023, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwedt, T.J.; Digre, K.; Tepper, S.J.; Spare, N.M.; Ailani, J.; Birlea, M.; Burish, M.; Mechtler, L.; Gottschalk, C.; Quinn, A.M.; et al. The American Registry for Migraine Research: Research Methods and Baseline Data for an Initial Patient Cohort. Headache 2020, 60, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Schulte, L.; May, A. The 15-day threshold in the definition of chronic migraine is reasonable and sufficient-Five reasons for not changing the ICHD-3 definition. Headache 2022, 62, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hernández, A.; Marichal-Cancino, B.A.; García-Boll, E.; Villalón, C.M. The locus of Action of CGRPergic Monoclonal Antibodies Against Migraine: Peripheral Over Central Mechanisms. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 19, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannone, L.F.; De Cesaris, F.; Ferrari, A.; Benemei, S.; Fattori, D.; Chiarugi, A. Effectiveness of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies on central symptoms of migraine. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Chawla, E. Efficacy and safety of anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies for treatment of chronic migraine: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021, 209, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Cheng, H.; Xia, B.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Five Anti-calcitonin Gene-related Peptide Agents for Migraine Prevention: A Network Meta-analysis. Clin. J. Pain 2023, 39, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikelis, M.; Rikos, D.; Argyriou, A.A.; Dermitzakis, E.V.; Andreou, A.P.; Russo, A. Switching between anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in migraine prophylaxis. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2025, 25, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimia, P.; Santos-Lasaosa, S.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Leira, R.; Pascual, J.; Láinez, J.M.; Láinez, J.M. Eptinezumab for the preventive treatment of episodic and chronic migraine: A narrative review. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1355877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Martinez, L.F.; Raport, C.J.; Ojala, E.W.; Dutzar, B.; Anderson, K.; Stewart, E.; Kovacevich, B.; Baker, B.; Billgren, J.; Scalley-Kim, M.; et al. Pharmacologic Characterization of ALD403, a Potent Neutralizing Humanized Monoclonal Antibody Against the Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 374, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, B.; Schaeffler, B.; Beliveau, M.; Rubets, I.; Pederson, S.; Trinh, M.; Smith, J.; Latham, J. Population pharmacokinetic and exposure-response analysis of eptinezumab in the treatment of episodic and chronic migraine. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spuntarelli, V.; Negro, A.; Luciani, M.; Bentivegna, E.; Martelletti, P. Eptinezumab for the treatment of migraine. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2021, 21, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashina, M.; Saper, J.; Cady, R.; Schaeffler, B.A.; Biondi, D.M.; Hirman, J.; Pederson, S.; Allan, B.; Smith, J. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodick, D.W.; Gottschalk, C.; Cady, R.; Hirman, J.; Smith, J.; Snapinn, S. Eptinezumab Demonstrated Efficacy in Sustained Prevention of Episodic and Chronic Migraine Beginning on Day 1 After Dosing. Headache 2020, 60, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, R.B.; Goadsby, P.J.; Smith, J.; Schaeffler, B.A.; Biondi, D.M.; Hirman, J.; Pederson, S.; Allan, B.; Cady, R. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology 2020, 94, e1365–e1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, P.K.; McAllister, P.; Chakhava, G.; Ailani, J.; Ettrup, A.; Josiassen, M.K.; Lindsten, A.; Mehta, L.; Cady, R. Effects of Intravenous Eptinezumab vs. Placebo on Headache Pain and Most Bothersome Symptom When Initiated During a Migraine Attack: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 2348–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailani, J.; McAllister, P.; Winner, P.K.; Chakhava, G.; Josiassen, M.K.; Lindsten, A.; Sperling, B.; Ettrup, A.; Cady, R. Rapid resolution of migraine symptoms after initiating the preventive treatment eptinezumab during a migraine attack: Results from the randomized RELIEF trial. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.; Lipton, R.B.; Scher, A.I.; Reed, M.L.; Stewart, W.B.F.; Adams, A.M.; Buse, D.C. Fluctuations in episodic and chronic migraine status over the course of 1 year: Implications for diagnosis, treatment and clinical trial design. J. Headache Pain 2017, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Summary of Product Characteristics: Eptinezumab (VYEPTI). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vyepti-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Farrar, J.T.; Young, J.P., Jr.; LaMoreaux, L.; Werth, J.L.; Poole, R.M. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001, 94, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Martinez, M.D.; Goadsby, P.J. Pathophysiology and Therapy of Associated Features of Migraine. Cells 2022, 11, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dermitzakis, E.V.; Vikelis, M.; Xiromerisiou, G.; Rallis, D.; Soldatos, P.; Litsardopoulos, P.; Rikos, D.; Argyriou, A.A. Nine-Month Continuous Fremanezumab Prophylaxis on the Response to Triptans and Also on the Incidence of Triggers, Hypersensitivity and Prodromal Symptoms of Patients with High-Frequency Episodic Migraine. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.; Bolton, J. Assessing the clinical significance of change scores recorded on subjective outcome measures. J. Manip. Physiol. Ther. 2004, 27, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Wyrwich, K.W.; Beaton, D.; Cleeland, C.S.; Farrar, J.T.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Kerns, R.D.; Ader, D.N.; et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J. Pain 2008, 9, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamura, C.; Brunelli, N.; Marcosano, M.; Alesina, A.; Fofi, L.; Vernieri, F. Eptinezumab for the Prevention of Migraine: Clinical Utility, Patient Preferences and Selection—A Narrative Review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 959–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, E.; Ashina, S.; Melo-Carrillo, A.; Bolo, N.R.; Borsook, D.; Burstein, R. Peripherally acting anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies alter cortical gray matter thickness in migraine patients: A prospective cohort study. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 40, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krymchantowski, A.V.; Jevoux, C.C.; Krymchantowski, A.G.; Vivas, R.S.; Silva-Néto, R. Medication overuse headache: An overview of clinical aspects, mechanisms, and treatments. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2020, 20, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants n = 39 | |

|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) |

| Gender | |

| Females | 36 (92.3) |

| Males | 3 (7.7) |

| Age ± SD (range) | 48.1 ± 12.5 (18–68) |

| Previous lines of prophylactic medications | |

| median value (range) | 4 (3–10) |

| Years with chronic migraine diagnosis | |

| median value (range) | 27 (9–40) |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | |

| No | 9 (23.1) |

| Anxiety disorder | 10 (25.6) |

| Depression | 6 (15.4) |

| Mixed anxiety and depression disorder | 14 (35.9) |

| Medication overuse headache | |

| Yes | 35 (89.7) |

| No | 4 (10.3) |

| Aura | |

| Yes | 12 (30.8) |

| No | 27 (69.2) |

| Prior anti-CGRPs Mabs exposure | |

| Naive | 23 (59.0) |

| Anti-CGRP-receptor Mab and/or Anti-CGRP-ligand Mab | 16 (41.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Argyriou, A.A.; Dermitzakis, E.V.; Chondrogianni, M.; Foska, A.; Rikos, D.; Soldatos, P.; Vikelis, M., on behalf of the Greek Research Alliance for the Study of Headache and Pain (GRASP) Study Group. Testing the Efficacy of Eptinezumab 100 mg in the Early Prevention of Chronic Migraine over Weeks 1 to 4: Prospective Real-World Data from the GRASP Study Group. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248793

Argyriou AA, Dermitzakis EV, Chondrogianni M, Foska A, Rikos D, Soldatos P, Vikelis M on behalf of the Greek Research Alliance for the Study of Headache and Pain (GRASP) Study Group. Testing the Efficacy of Eptinezumab 100 mg in the Early Prevention of Chronic Migraine over Weeks 1 to 4: Prospective Real-World Data from the GRASP Study Group. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248793

Chicago/Turabian StyleArgyriou, Andreas A., Emmanouil V. Dermitzakis, Maria Chondrogianni, Aikaterini Foska, Dimitrios Rikos, Panagiotis Soldatos, and Michail Vikelis on behalf of the Greek Research Alliance for the Study of Headache and Pain (GRASP) Study Group. 2025. "Testing the Efficacy of Eptinezumab 100 mg in the Early Prevention of Chronic Migraine over Weeks 1 to 4: Prospective Real-World Data from the GRASP Study Group" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248793

APA StyleArgyriou, A. A., Dermitzakis, E. V., Chondrogianni, M., Foska, A., Rikos, D., Soldatos, P., & Vikelis, M., on behalf of the Greek Research Alliance for the Study of Headache and Pain (GRASP) Study Group. (2025). Testing the Efficacy of Eptinezumab 100 mg in the Early Prevention of Chronic Migraine over Weeks 1 to 4: Prospective Real-World Data from the GRASP Study Group. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8793. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248793