Prediction of Cardiogenic Shock in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Using a Nomogram

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

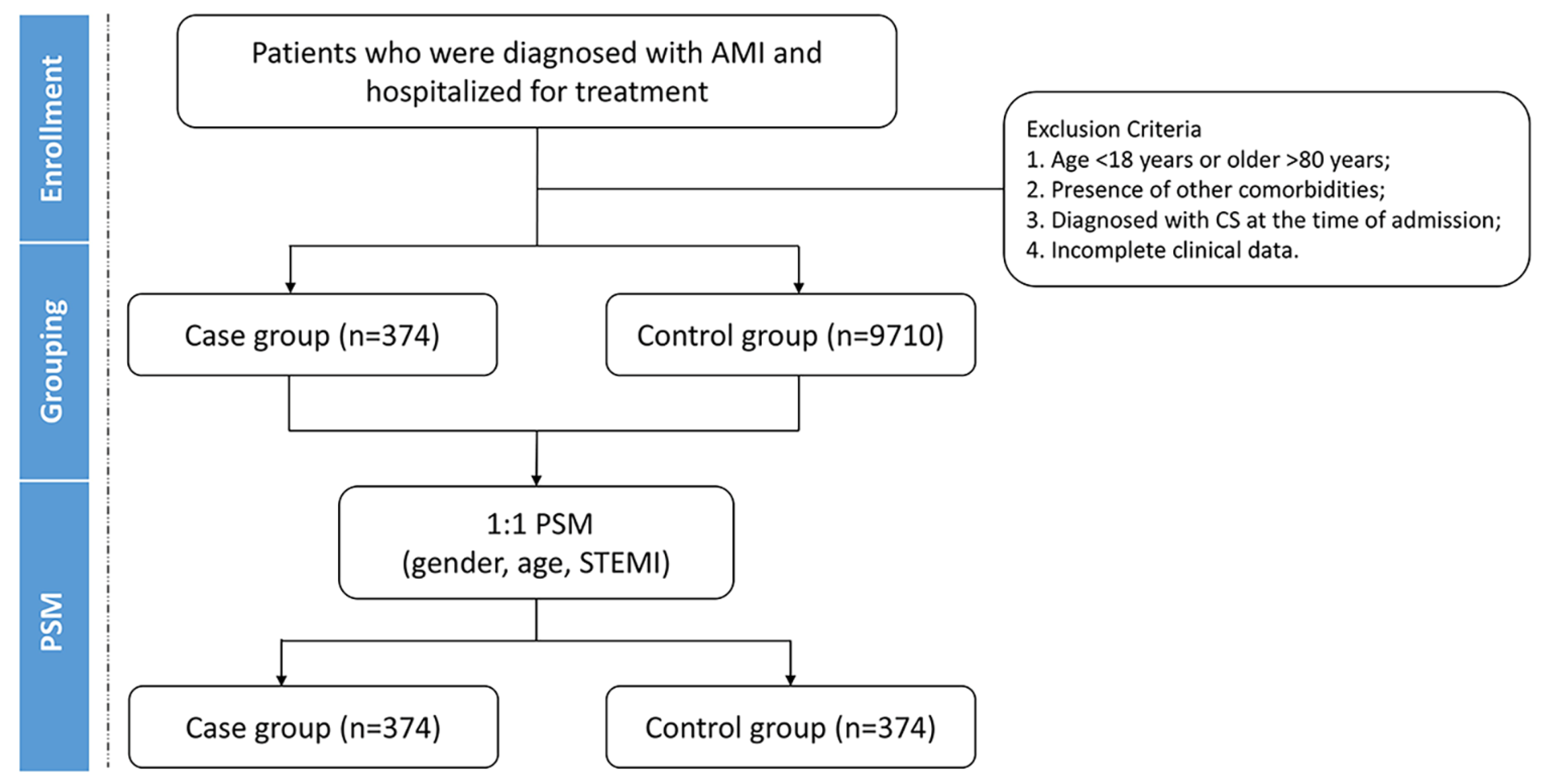

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Grouping and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

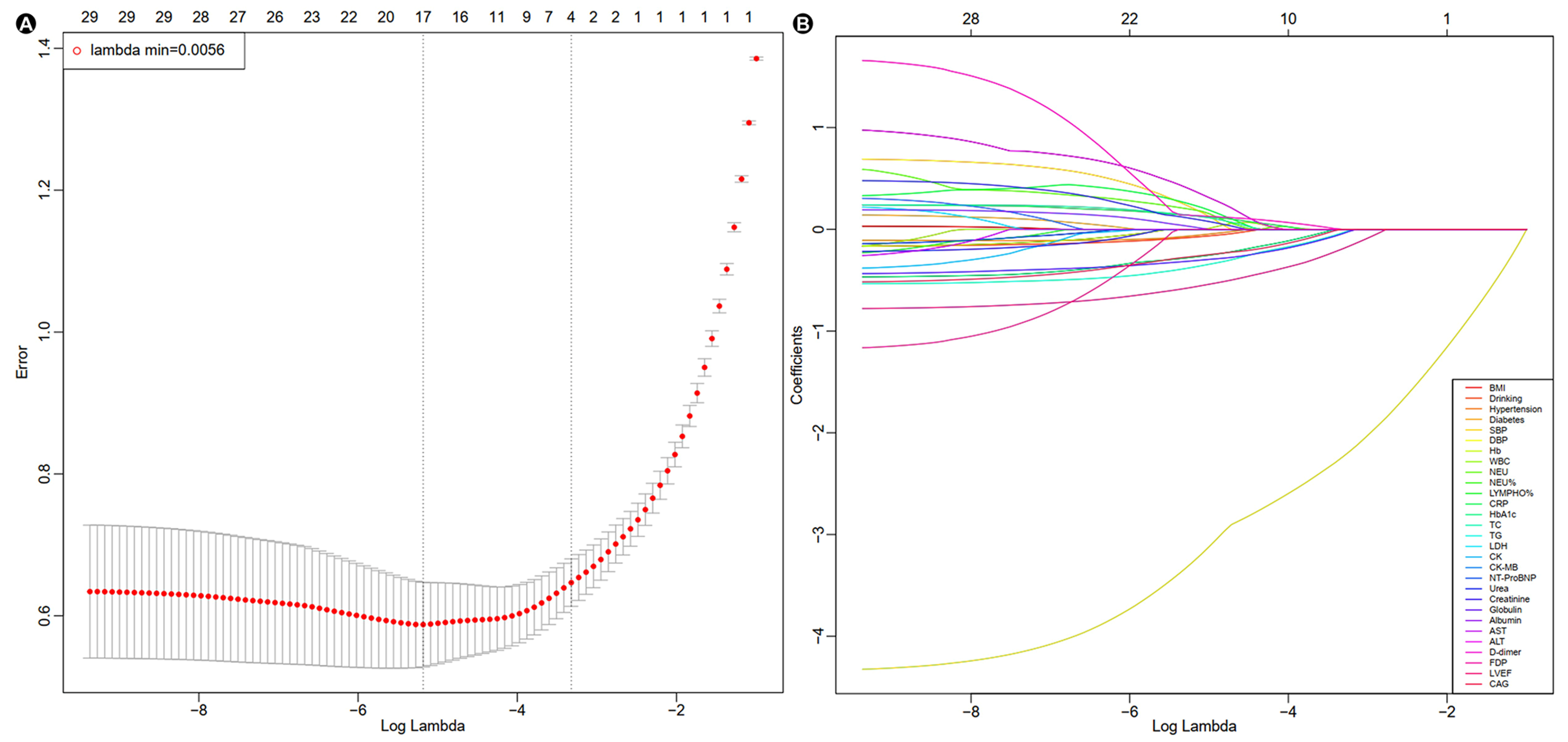

3.2. LASSO-Logistic Regression and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

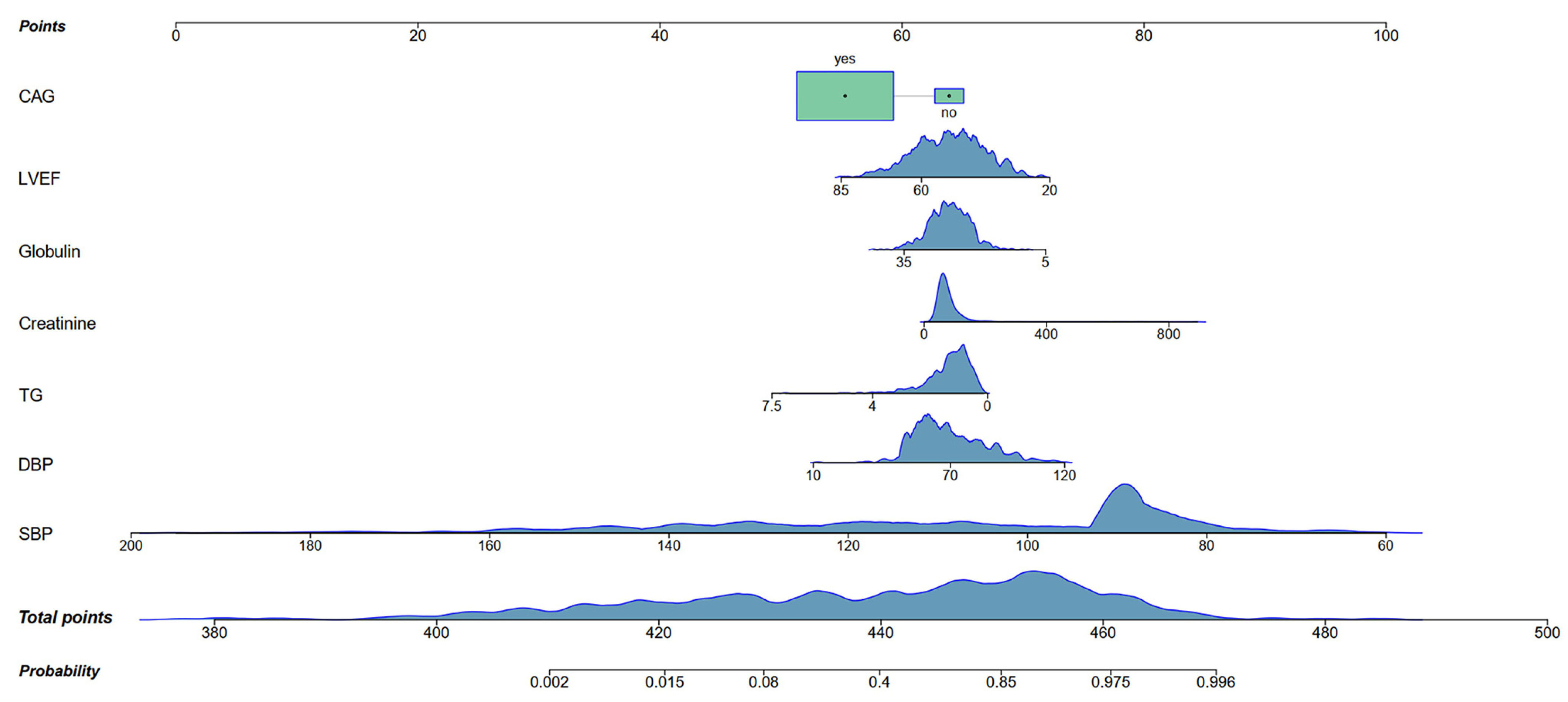

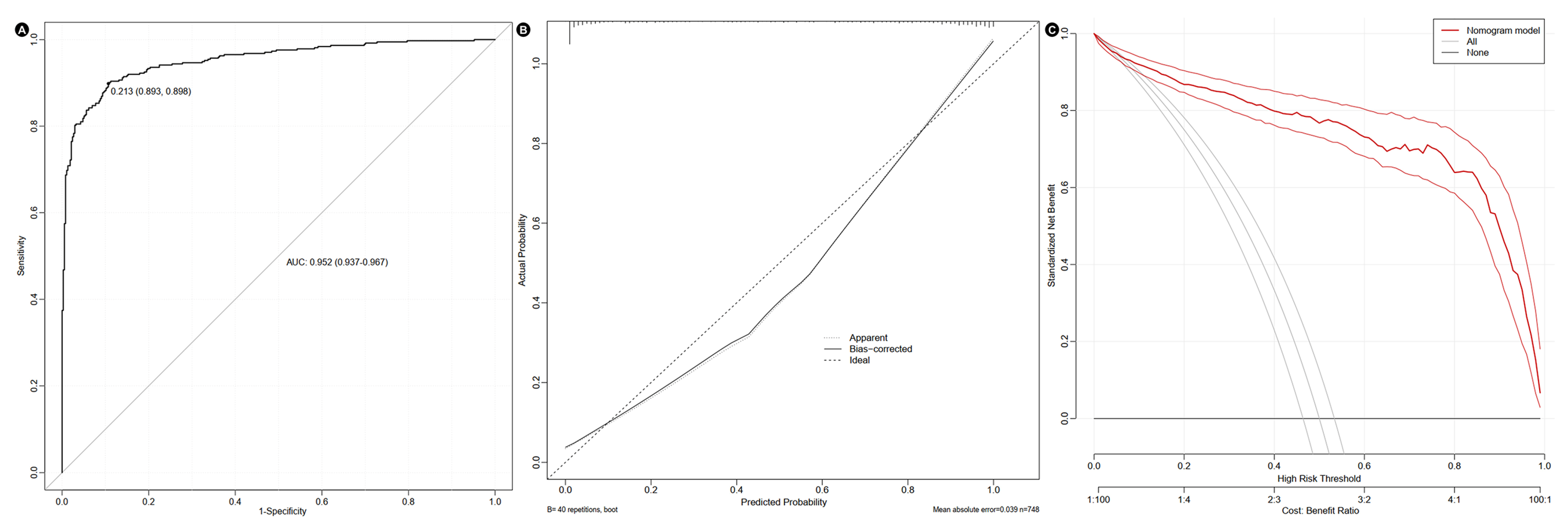

3.3. Construction of Nomogram

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMI | Acute myocardial infarction |

| CS | Cardiogenic shock |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| CAG | Coronary angiography |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

References

- Chew, N.W.S.; Ng, C.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Kong, G.; Lin, C.; Chin, Y.H.; Lim, W.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Quek, J.; Fu, C.E.; et al. The global burden of metabolic disease: Data from 2000 to 2019. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 414–428.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, R.X. Protective Mechanisms of Quercetin Against Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrère-Lemaire, S.; Vincent, A.; Jorgensen, C.; Piot, C.; Nargeot, J.; Djouad, F. Mesenchymal stromal cells for improvement of cardiac function following acute myocardial infarction: A matter of timing. Physiol. Rev. 2024, 104, 659–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishu, K.G.; Lekoubou, A.; Kirkland, E.; Schumann, S.O.; Schreiner, A.; Heincelman, M.; Moran, W.P.; Mauldin, P.D. Estimating the Economic Burden of Acute Myocardial Infarction in the US: 12 Year National Data. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 359, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, J.S.; Sleeper, L.A.; Webb, J.G.; Sanborn, T.A.; White, H.D.; Talley, J.D.; Buller, C.E.; Jacobs, A.K.; Slater, J.N.; Col, J.; et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioncel, O.; Parissis, J.; Mebazaa, A.; Thiele, H.; Desch, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Harjola, V.P.; Antohi, E.L.; Arrigo, M.; Ben Gal, T.; et al. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and contemporary management of cardiogenic shock—A position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1315–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, D.D.; Bohula, E.A.; van Diepen, S.; Katz, J.N.; Alviar, C.L.; Baird-Zars, V.M.; Barnett, C.F.; Barsness, G.W.; Burke, J.A.; Cremer, P.C.; et al. Epidemiology of Shock in Contemporary Cardiac Intensive Care Units. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.; Bortone, A.S.; Giordano, A.; Cecere, A.; Burattini, O.; Nestola, P.L.; Patti, G.; Di Cillo, O.; Signore, N.; Forleo, C.; et al. Cardiogenic Shock Following Acute Myocardial Infarction: What’s New? Shock 2020, 53, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentzer, J.C.; van Diepen, S.; Barsness, G.W.; Henry, T.D.; Menon, V.; Rihal, C.S.; Naidu, S.S.; Baran, D.A. Cardiogenic Shock Classification to Predict Mortality in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation 2018, 138, e618–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, R.; Pahuja, M.; van Diepen, S.; Proudfoot, A.G.; Morrow, D.; Spitzer, E.; Nichol, G.; Weisfeldt, M.L.; Moscucci, M.; Lawler, P.R.; et al. Standardized Definitions for Cardiogenic Shock Research and Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices: Scientific Expert Panel From the Shock Academic Research Consortium (SHARC). Circulation 2023, 148, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, S.S.; Baran, D.A.; Jentzer, J.C.; Hollenberg, S.M.; van Diepen, S.; Basir, M.B.; Grines, C.L.; Diercks, D.B.; Hall, S.; Kapur, N.K.; et al. SCAI SHOCK Stage Classification Expert Consensus Update: A Review and Incorporation of Validation Studies: This statement was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), American Heart Association (AHA), European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Association for Acute Cardiovascular Care (ACVC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in December 2021. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, D.; Jentzer, J.C. Cardiogenic Shock: Pathogenesis, Classification, and Management. Crit. Care Clin. 2024, 40, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, B.N.; Jentzer, J.C.; Weimann, J.; Dabboura, S.; Yan, I.; Sundermeyer, J.; Kirchhof, P.; Blankenberg, S.; Schrage, B.; Westermann, D. Early risk stratification in patients with cardiogenic shock irrespective of the underlying cause—The Cardiogenic Shock Score. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, J.E.; Harris, T.; Dünser, M.W.; Bouzat, P.; Gauss, T. Vasopressors in Trauma: A Never Event? Anesth. Analg. 2021, 133, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, F.; Sanz-Ruiz, R.; Sabate, M.; Macaya, F.; Roura, G.; Jimenez-Kockar, M.; Nogales, J.M.; Velazquez, M.; Veiga, G.; Camacho-Freire, S.; et al. Clinical Implications of the “Broken Line” Angiographic Pattern in Patients With Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 185, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjević, A.; Šušak, S.; Velicki, L.; Antonič, M. Acute kidney injury after open-heart surgery procedures. Acta Clin. Croat. 2021, 60, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; De, A.; Aggrawal, R.; Singh, A.; Charak, S.; Bhagat, N. Safety and Efficacy of Dapagliflozin in Recurrent Ascites: A Pilot Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, 70, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryczka, K.E.; Kruk, M.; Demkow, M.; Lubiszewska, B. Fibrinogen and a Triad of Thrombosis, Inflammation, and the Renin-Angiotensin System in Premature Coronary Artery Disease in Women: A New Insight into Sex-Related Differences in the Pathogenesis of the Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, G.; Tanaka, A.; Goriki, Y.; Node, K. The role of albumin level in cardiovascular disease: A review of recent research advances. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2022, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäntti, T.; Tarvasmäki, T.; Harjola, V.P.; Parissis, J.; Pulkki, K.; Javanainen, T.; Tolppanen, H.; Jurkko, R.; Hongisto, M.; Kataja, A.; et al. Hypoalbuminemia is a frequent marker of increased mortality in cardiogenic shock. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, R.C.; Trivette, E.T.; Westerfield, K.L. Management of Hypertriglyceridemia: Common Questions and Answers. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.C.; Chang, C.H. Activation of the basolateral or the central amygdala dampened the incentive motivation for food reward on high fixed-ratio schedules. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 455, 114682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhasin, E.; Mishra, S.; Pathak, G.; Chauhan, P.S.; Kulshreshtha, A. Cytokine database of stress and metabolic disorders (CdoSM): A connecting link between stress and cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes and obesity. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lei, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, K.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: From a Very Low-Density Lipoprotein Perspective. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Boris, A.F.; Zhu, Y.; Gan, H.; Hu, X.; Xue, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Sasmita, B.R.; Liu, G.; Luo, S.; et al. Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Short-Term Prognosis in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock and Various Left Ventricular Ejection Fractions After Acute Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 167, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jozwiak, M.; Lim, S.Y.; Si, X.; Monnet, X. Biomarkers in cardiogenic shock: Old pals, new friends. Ann. Intensive Care 2024, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Before PSM (n = 10,084) | After PSM (n = 748) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Group | Control Group | p Value | Case Group | Control Group | p Value | |

| n = 374 | n = 9710 | n = 374 | n = 374 | |||

| Male (n, %) | 272 (72.7) | 7903 (81.4) | <0.001 | 272 (72.7) | 274 (73.3) | 0.869 |

| Age (years) | 63 (55, 71) | 61 (52, 69) | <0.001 | 63 ± 12 | 63 ± 11 | 0.954 |

| STEMI (n, %) | 263 (70.3) | 5600 (57.7) | <0.001 | 263 (70.3) | 264 (70.6) | 0.936 |

| Characteristics | Total | Case Group | Control Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 748 | n = 374 | n = 374 | ||

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.13 ± 3.14 | 23.73 ± 3.23 | 24.52 ± 2.99 | 0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 223 (29.8) | 111 (29.7) | 112 (29.9) | 0.936 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 95 (12.7) | 39 (10.4) | 56 (15.0) | 0.062 |

| Recurrent AMI, n (%) | 45 (6.0) | 25 (6.7) | 20 (5.3) | 0.442 |

| Medical History, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 344 (46.0) | 141 (37.7) | 203 (54.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 232 (31.0) | 102 (27.3) | 130 (34.8) | 0.027 |

| Vital signs | ||||

| Heart rates (beats/min) | 75 (65, 86) | 76 (63, 89) | 75 (67, 84.50) | 0.917 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 103 (89, 129) | 89 (84, 90) | 126 (111, 140) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 67 (58, 80) | 59 (54, 65) | 77 (68, 88) | <0.001 |

| Biochemical Parameters | ||||

| Hb (g/L) | 136 (123, 148) | 134 (120, 147) | 139 (126, 150) | 0.001 |

| WBC (109/L) | 9.59 (7.18, 12.18) | 10.47 (7.80, 13.16) | 8.76 (6.82, 11.16) | <0.001 |

| NEU (109/L) | 7.56 (5.15, 10.37) | 8.34 (5.60, 11.31) | 6.56 (4.81, 9.22) | <0.001 |

| NEU% (%) | 79.10 (71.32, 86.10) | 81.05 (72.90, 86.70) | 77.10 (69.05, 84.33) | <0.001 |

| LYMPHO (109/L) | 1.33 (0.93, 1.85) | 1.37 (0.92, 1.89) | 1.30 (0.95, 1.80) | 0.498 |

| LYMPHO% (%) | 14.62 (9.46, 21.54) | 13.45 (8.85, 19.89) | 15.70 (10.06, 23.52) | 0.002 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 55.05 (27.49, 84.90) | 58.78 (31.90, 85.84) | 49.63 (21.43, 83.46) | 0.036 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.90 (5.00, 7.00) | 5.80 (5.50, 6.50) | 6.10 (5.60, 7.50) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.17 (1.64, 2.82) | 2.16 (1.60, 2.84) | 2.20 (1.68, 2.78) | 0.437 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.07) | 0.93 (0.82, 1.08) | 0.93 (0.79, 1.07) | 0.526 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.88 (3.23, 4.62) | 3.79 (3.15, 4.57) | 3.95 (3.29, 4.69) | 0.091 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.18 (0.82, 1.69) | 1.08 (0.73, 1.53) | 1.27 (0.90, 1.80) | <0.001 |

| hs-cTnT (ng/dL) | 0.56 (0.11, 1.99) | 0.60 (0.13, 2.37) | 0.54 (0.10, 1.61) | 0.161 |

| hs-cTnI (ng/dL) | 1590.55 (239.33, 9741.61) | 2580.73 (295.36, 18,365.53) | 1194.84 (227.67, 6812.40) | 0.260 |

| LDH (U/L) | 320.00 (231.00, 554.00) | 350.00 (240.50, 655.75) | 292.50 (228.00, 439.25) | <0.001 |

| CK (U/L) | 387.00 (119.09, 1236.50) | 587.14 (145.50, 1460.00) | 301.00 (107.75, 901.00) | <0.001 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 45.65 (18.00, 147.75) | 63.40 (20.04, 176.63) | 33.00 (16.00, 109.93) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1001.85 (326.35, 2973.38) | 1372.50 (330.25, 3553.65) | 813.10 (315.18, 2295.75) | 0.002 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 5.91 (4.76, 7.56) | 6.16 (4.94, 7.85) | 5.57 (4.55, 7.10) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 67.00 (55.00, 85.00) | 72.00 (57.00, 96.00) | 64.50 (53.00, 79.25) | <0.001 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 25.43 ± 4.33 | 24.76 ± 4.47 | 26.10 ± 4.08 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36.97 ± 5.06 | 36.30 ± 5.12 | 37.65 ± 4.91 | <0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 61.00 (29.00, 170.00) | 84.00 (32.00, 240.00) | 49.00 (27.00, 124.50) | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 37.00 (22.00, 63.00) | 41.50 (24.75, 72.50) | 32.00 (21.00, 58.50) | <0.001 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.68 (0.38, 1.52) | 0.83 (0.46, 2.32) | 0.55 (0.33, 1.01) | <0.001 |

| FDP (mg/L) | 2.22 (1.30, 5.41) | 2.50 (1.50, 7.55) | 2.00 (1.20, 3.60) | <0.001 |

| Echocardiology | ||||

| LVEF (%) | 51 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 | 54 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| Aortic regurgitation, n (%) | 17 (2.3) | 6 (1.6) | 11 (2.9) | 0.220 |

| Mitral regurgitation, n (%) | 89 (11.9) | 45 (12.0) | 44 (11.8) | 0.910 |

| Treatment | ||||

| PCI, n (%) | 621 (83.0) | 303 (81.0) | 318 (85.0) | 0.144 |

| CAG, n (%) | 687 (91.8) | 330 (88.2) | 357 (95.5) | <0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| In-hospital stay (days) | 4 (3, 7) | 5 (3, 7) | 4 (2, 6) | 0.009 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 26 (3.5) | 20 (5.3) | 6 (1.6) | 0.005 |

| Characteristics | LASSO-Logistic Regression | Multivariate Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assignment | Coefficient | OR (95%CI) | p-Value | |

| BMI | Continuous variable | |||

| Drinking | Yes = 1, No = 0 | −0.1438 | 0.636 (0.309, 1.310) | 0.220 |

| Hypertension | Yes = 1, No = 0 | −0.1433 | 1.062 (0.634, 1.781) | 0.819 |

| Diabetes | Yes = 1, No = 0 | |||

| SBP | Continuous variable | −4.2030 | 0.866 (0.844, 0.888) | <0.001 |

| DBP | Continuous variable | 0.6490 | 1.031 (1.001, 1.063) | 0.046 |

| Hb | Continuous variable | |||

| WBC | Continuous variable | |||

| NEU | Continuous variable | 0.3581 | 1.059 (0.978, 1.146) | 0.161 |

| NEU% | Continuous variable | |||

| LYMPHO% | Continuous variable | 0.5165 | 1.026 (0.989, 1.064) | 0.166 |

| CRP | Continuous variable | 0.2092 | 1.005 (0.999, 1.011) | 0.119 |

| HbA1c | Continuous variable | −0.3994 | 0.877 (0.730, 1.054) | 0.161 |

| TC | Continuous variable | 0.2540 | 1.273 (0.960, 1.688) | 0.093 |

| TG | Continuous variable | −0.5480 | 0.561 (0.385, 0.820) | 0.003 |

| LDH | Continuous variable | |||

| CK | Continuous variable | |||

| CK-MB | Continuous variable | |||

| NT-ProBNP | Continuous variable | |||

| Urea | Continuous variable | |||

| Creatinine | Continuous variable | 0.2631 | 1.005 (1.000, 1.010) | 0.048 |

| Globulin | Continuous variable | −0.3917 | 0.915 (0.862, 0.972) | 0.004 |

| Albumin | Continuous variable | 0.1642 | 1.034 (0.976, 1.095) | 0.256 |

| AST | Continuous variable | |||

| ALT | Continuous variable | 0.8541 | 1.002 (0.999, 1.004) | 0.050 |

| D-dimer | Continuous variable | 0.1874 | 1.027 (0.985, 1.071) | 0.206 |

| FDP | Continuous variable | |||

| LVEF | Continuous variable | −0.7371 | 0.951 (0.928,0.975) | <0.001 |

| CAG | Yes = 1, No = 0 | −0.3858 | 0.183 (0.058, 0.574) | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Yang, C.; Dong, Y.; Yang, X.; Sun, C. Prediction of Cardiogenic Shock in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Using a Nomogram. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248789

Wang J, Zhao C, Yang C, Dong Y, Yang X, Sun C. Prediction of Cardiogenic Shock in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Using a Nomogram. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248789

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jie, Changying Zhao, Chuqing Yang, Yang Dong, Xiaohong Yang, and Chaofeng Sun. 2025. "Prediction of Cardiogenic Shock in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Using a Nomogram" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248789

APA StyleWang, J., Zhao, C., Yang, C., Dong, Y., Yang, X., & Sun, C. (2025). Prediction of Cardiogenic Shock in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Using a Nomogram. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8789. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248789