A Retrospective Cohort Study on Hassab’s Surgery as a Salvage Treatment for Patients with Secondary Prophylaxis Failure for Acute Variceal Bleeding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Preoperative Management

2.3. A 3D Reconstruction Technique Was Used to Design Individualized Hassab’s Surgery

2.4. Postoperative Management and Follow-Up

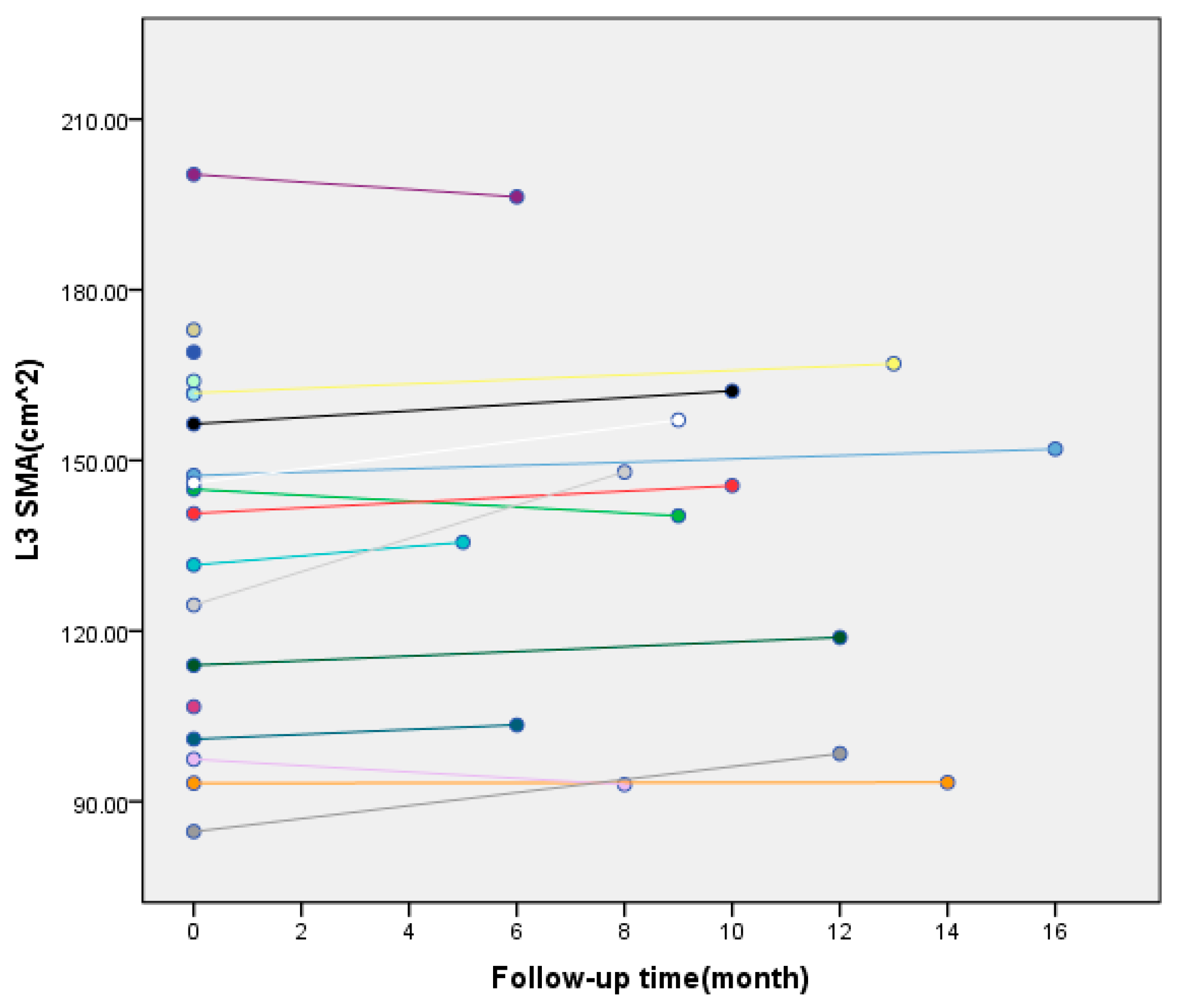

2.5. Measurement of L3 Skeletal Muscle Area (L3-SMA) Before and After Surgery

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Perioperative Complications

3.3. Comparison of Laboratory Indicators Before and After Surgery in the Experimental Group

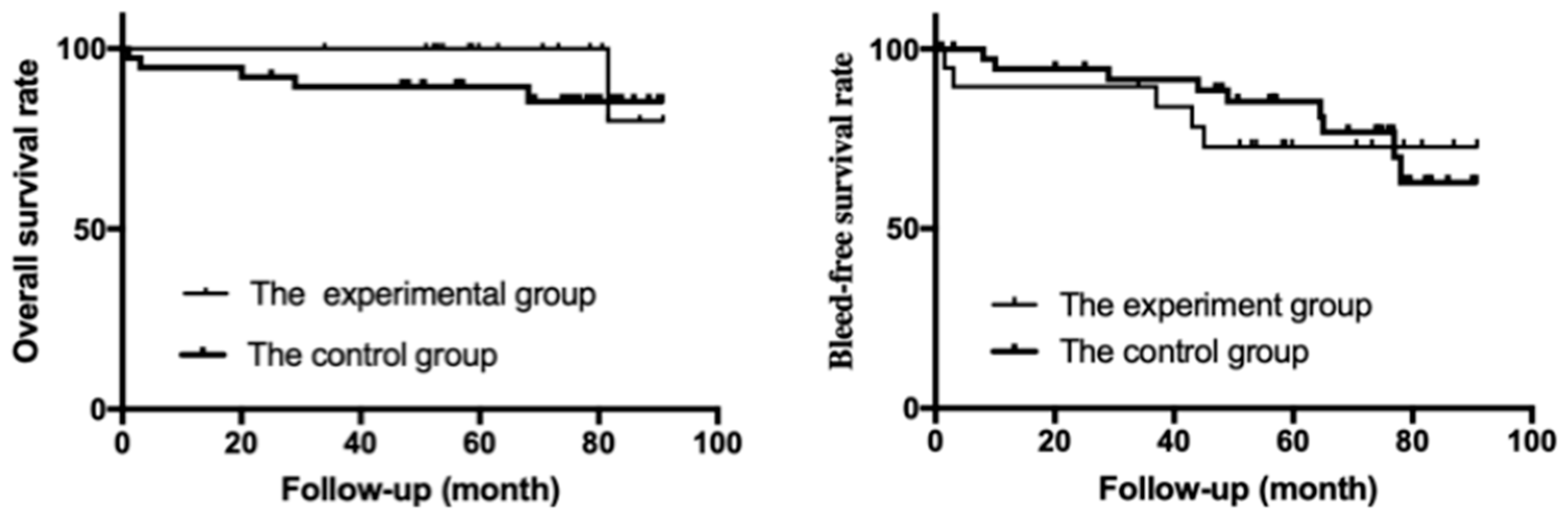

3.4. Re-Bleeding-Free Survival and Overall Survival (OS)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iwakiri, Y.; Trebicka, J. Portal hypertension in cirrhosis: Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapy. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McConnell, M.; Iwakiri, Y. Biology of portal hypertension. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Tsao, G.; Abraldes, J.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Bosch, J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2017, 65, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakab, S.S.; Garcia-Tsao, G. Evaluation and Management of EGV in Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2020, 24, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 406–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL). KASL clinical practice guidelines for liver cirrhosis: Varices, hepatic encephalopathy, and related complications. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2020, 26, 83–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Society of Hepatology; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; Chinese Society of Digestive Endoscopology of Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal and gastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension Chinese Society of Hepatology. J. Clin. Hepatol. 2016, 32, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Society of Spleen and Portal Hypertension Surgery; Chinese Society of Surgery; Chinese Medical Association. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of esophagogastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension (2019 edition). Chin. J. Dig. Surg. 2019, 57, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Luo, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Wei, F.; Zhang, Y. Selective Esophagogastric Devascularization in the Modified Sugiura Procedure for Patients with Cirrhotic Hemorrhagic Portal Hypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 2020, 8839098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paugam-Burtz, C.; Janny, S.; Delefosse, D.; Dahmani, S.; Dondero, F.; Mantz, J.; Belghiti, J. Prospective validation of the “fifty-fifty” criteria as an early and accurate predictor of death after liver resection in intensive care unit patients. Ann. Surg. 2009, 249, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshita, K.; Ohira, M.; Honmyo, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Murakami, E.; Aikata, H.; Baba, Y.; Kawano, R.; Awai, K.; Chayama, K.; et al. Treatment outcomes after splenectomy with gastric devascularization or balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices: A propensity score-weighted analysis from a single institution. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Wei, F.X.; Wei, Z.G.; Wang, G.N.; Wang, M.C.; Zhang, Y.C. Elective Splenectomy Combined with Modified Hassab’s or Sugiura Procedure for Portal Hypertension in Decompensated Cirrhosis. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 1208614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Faculty, B., VII. Baveno VII—Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkash, O.; Jafri, W.; Munir, S.M.; Iqbal, R. Assessment of malnutrition in patients with liver cirrhosis using protein calorie malnutrition (PCM) score verses bio-electrical impedance analysis (BIA). BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Carvalho, L.; Parise, E.R.; Samuel, D. Factors associated with nutritional status in liver transplant patients who survived the first year after transplantation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holster, I.L.; Tjwa, E.T.; Moelker, A.; Wils, A.; Hansen, B.E.; Vermeijden, J.R.; Scholten, P.; van Hoek, B.; Nicolai, J.J.; Kuipers, E.J.; et al. Covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic therapy + beta-blocker for prevention of variceal rebleeding. Hepatology 2016, 63, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Han, G.; Guo, X. Covered TIPS for secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2016, 95, e5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, G.; Pasta, L.; Morabito, A.; D’Amico, M.; Caltagirone, M.; Malizia, G.; Tinè, F.; Giannuoli, G.; Traina, M.; Vizzini, G.; et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: A 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 39, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Franchis, R.; Faculty, B., VI. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, Z.; Patel, K.; Patton, H.; Saad, W. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Bleeding Gastric Varices: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1098–1107.e1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Experimental Group (n = 19) | Control Group (n = 47) | Statistic | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years old, median (range) | 46 (27–64) | 49 (23–70) | −0.057 | 0.955 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 14 (73.7) | 36 (76.6) | 0.000 | 1.000 * |

| Etiology | 0.176 | 1.000 | ||

| HBV infection, n (%) | 13 (68.4) | 32 (68.1) | ||

| HCV infection, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (6.4) | ||

| Alcoholic liver disease, n (%) | 5 (26.3) | 12 (25.0) | ||

| History of smoking, Y, n (%) | 8 (42.1) | 16 (34.0) | 0.380 | 0.538 |

| History of drinking, Y, n (%) | 5 (26.3) | 10 (21.3) | 0.748 * | |

| Laboratory tests after admission | ||||

| White blood cell count, median (range) × 109/L | 1.64 (1.1–10.04) | 2.18 (0.94–12.03) | −1.282 | 0.200 |

| Platelet count, median (range) × 109/L | 36 (13.0–74.0) | 48.5 (15.4–169.0) | −0.432 | 0.666 |

| Hemoglobin, median (range) g/dL | 85 (59–115) | 89 (58–136) | −0.637 | 0.524 |

| Prothrombin activity, median (range) % | 59 (43–75) | 63 (41–89) | −0.057 | 0.955 |

| INR, median (range) | 1.42 (1.15–1.84) | 1.38 (1.10–1.94) | −0.716 | 0.474 |

| Child–Pugh classification, A/B/C, n (%) | 12 (63.2)/7 (36.8)/0 (0) | 31 (66.0)/14 (29.8)/2 (4.3) | 0.729 | 0.885 * |

| MELD score | 10 (2–15) | 10 (1–16) | −0.107 | 0.915 |

| Operation time, median (range) minutes | 180 (100–390) | 162.5 (90–420) | −0.724 | 0.469 |

| Blood loss, median (range) mL | 200 (100–900) | 200 (50–1500) | −0.169 | 0.866 |

| Clavien–Dindo Classification | Complication | Experimental Group n (%) | Control Group n (%) | Statistic | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | |||||

| Body temperature ≥38.5 °C | 8 (42.1) | 28 (59.6) | 1.665 | 0.276 | |

| Infection of incisional wound | 3 (15.8) | 8 (17.0) | - | 1.000 * | |

| Ascites (>500 mL/day) | 8 (42.1) | 24 (51.1) | 0.510 | 0.592 | |

| II | |||||

| Portal vein thrombosis | 9 (47.4) | 12 (25.5) | 2.974 | 0.143 | |

| Gastroparesis | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | - | 0.288 * | |

| Abdominal infection | 1 (5.3) | 7 (14.9) | - | 0.422 * | |

| III | |||||

| IIIa | Abdominal bleeding (no surgery needed to stop bleeding) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | - | 0.288 * |

| IIIb | Abdominal bleeding (Conservative treatment failed and surgery was needed to stop bleeding) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | - | 1.000 * |

| Disruption of incisional wound | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | - | 1.000 * | |

| IV | |||||

| Iva | Postoperative liver failure | 1 (5.3) | 2 (4.3) | - | 1.000 * |

| IVb | Multiple organ dysfunction | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | - | 1.000 * |

| V | |||||

| Death | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | - | 1.000 * |

| Laboratory Indicators | Before Surgery | 3 Months After Surgery | Statistic | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count, median (range) × 109/L | 1.64 (1.1–10.04) | 5.98 (2.83–11.72) | −2.627 | 0.009 |

| Platelet count, median (range) × 109/L | 36 (13.0–74.0) | 336.00 (67.20–792.10) | −3.621 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, median (range) g/dL | 85 (59–115) | 101 (71–129) | −2.131 | 0.033 |

| INR, median (range) | 1.42 (1.15–1.84) | 1.21 (0.99–1.84) | −2.757 | 0.006 |

| Ascites, n (%) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (10.5) | - | 0.405 |

| Child–Pugh score, median (range) | 6 (5–9) | 5 (5–7) | −2.138 | 0.033 |

| MELD score, median (range) | 10 (2–15) | 8 (2–15) | −2.586 | 0.010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Xing, Y.; Wang, D.; He, R.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, L.; Jia, Z. A Retrospective Cohort Study on Hassab’s Surgery as a Salvage Treatment for Patients with Secondary Prophylaxis Failure for Acute Variceal Bleeding. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248772

Zhang H, Xing Y, Wang D, He R, Zhang K, Jiang L, Jia Z. A Retrospective Cohort Study on Hassab’s Surgery as a Salvage Treatment for Patients with Secondary Prophylaxis Failure for Acute Variceal Bleeding. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248772

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hongwei, Yuxue Xing, Danpu Wang, Rong He, Ke Zhang, Li Jiang, and Zhe Jia. 2025. "A Retrospective Cohort Study on Hassab’s Surgery as a Salvage Treatment for Patients with Secondary Prophylaxis Failure for Acute Variceal Bleeding" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248772

APA StyleZhang, H., Xing, Y., Wang, D., He, R., Zhang, K., Jiang, L., & Jia, Z. (2025). A Retrospective Cohort Study on Hassab’s Surgery as a Salvage Treatment for Patients with Secondary Prophylaxis Failure for Acute Variceal Bleeding. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8772. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248772