Four-Year Outcomes of aXess Arteriovenous Conduit in Hemodialysis Patients: Insights from Two Case Reports of the aXess FIH Study

Abstract

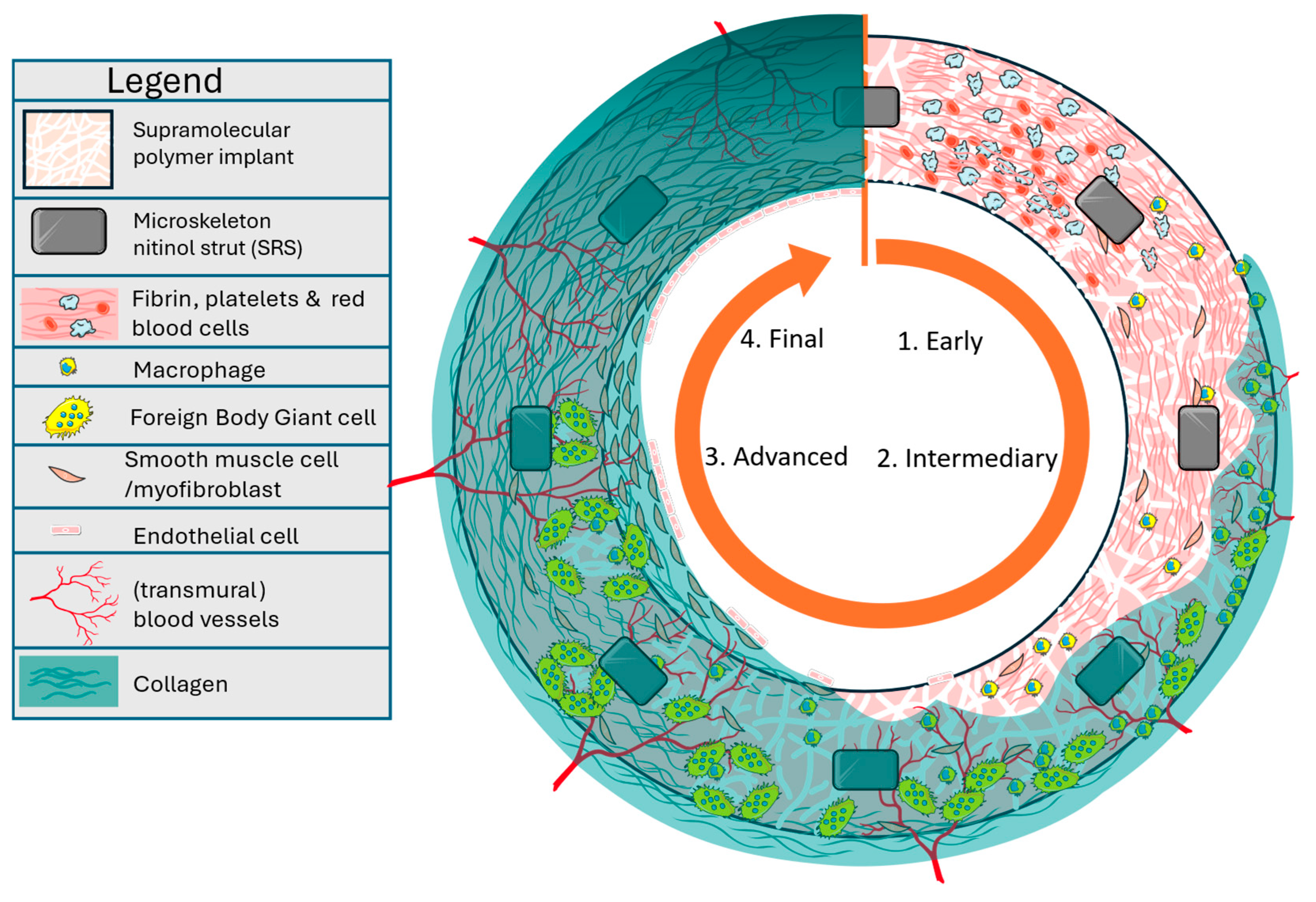

1. Introduction

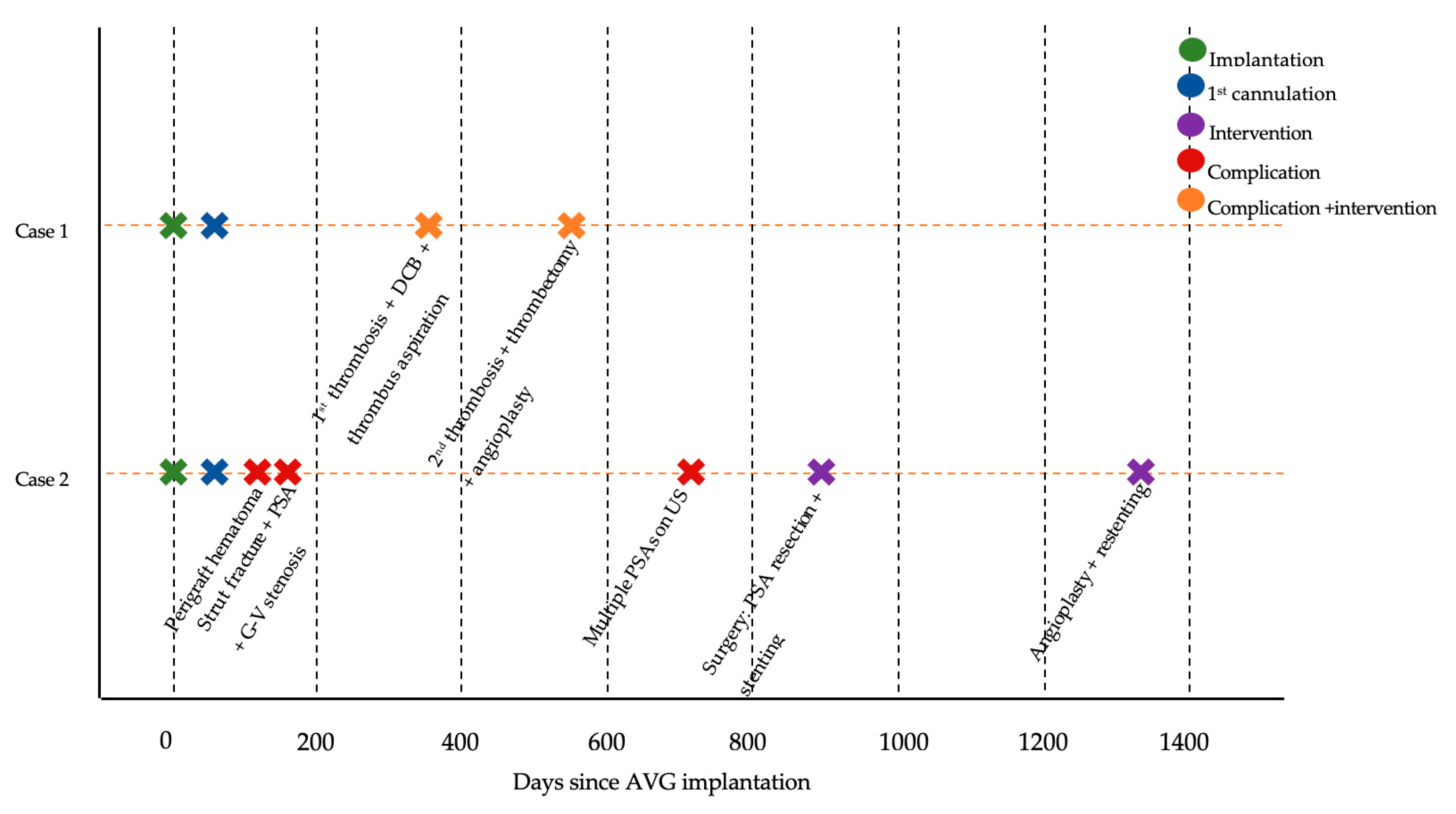

2. Case Reports

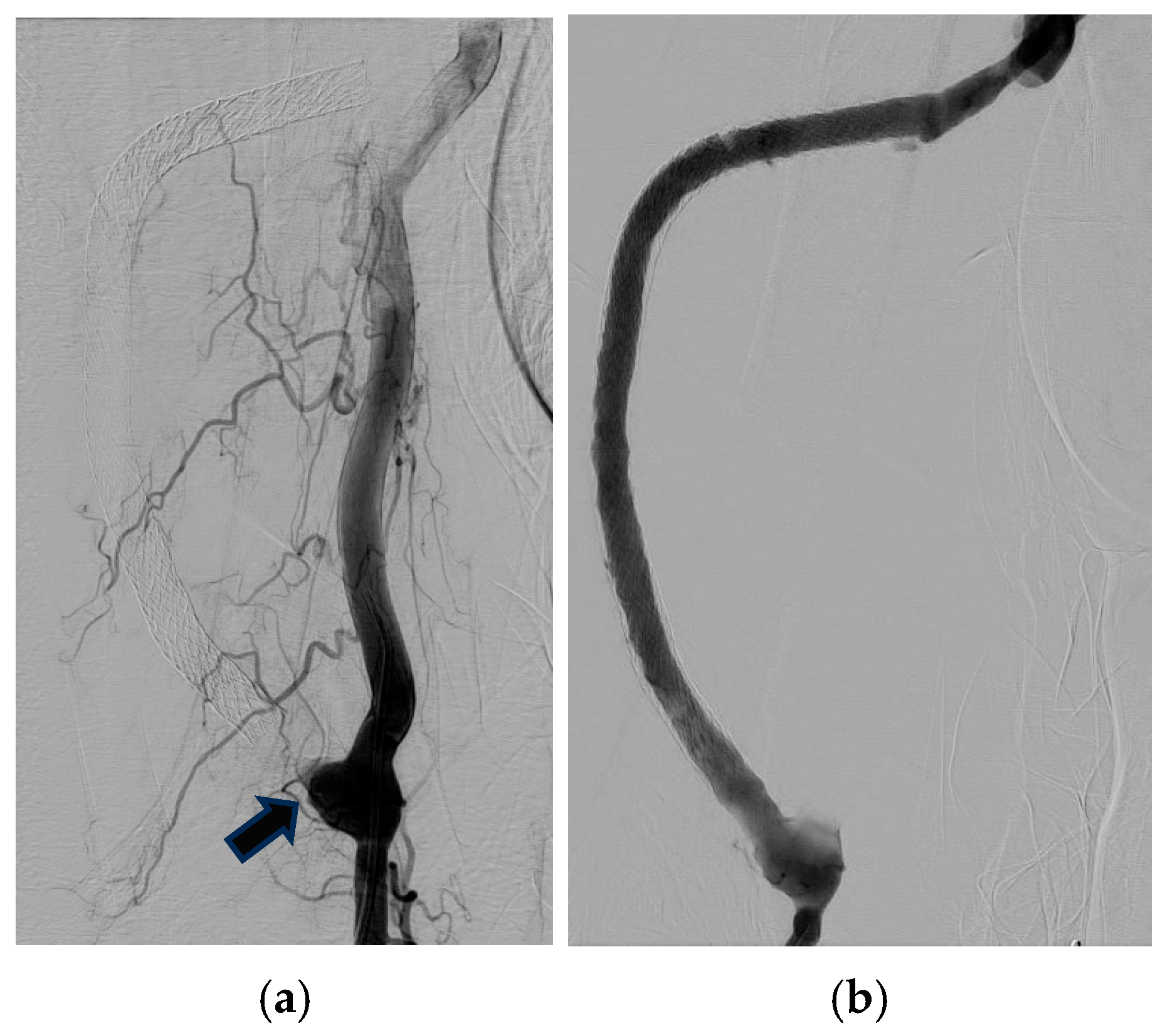

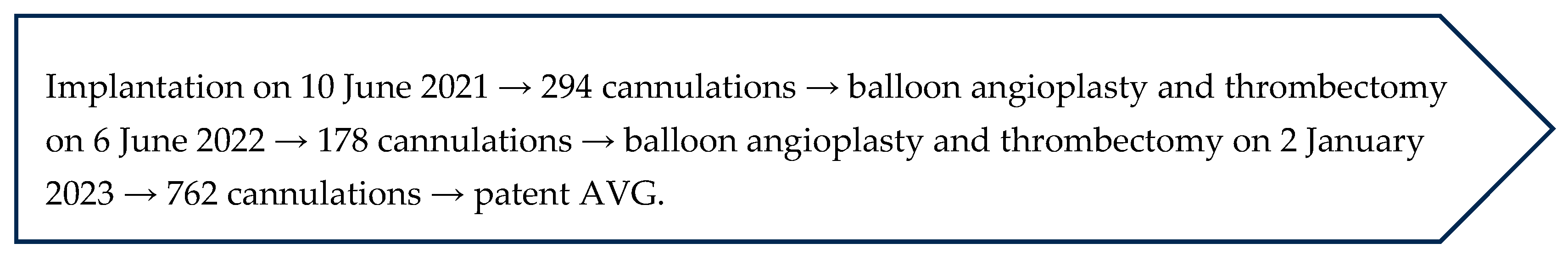

2.1. Case 1

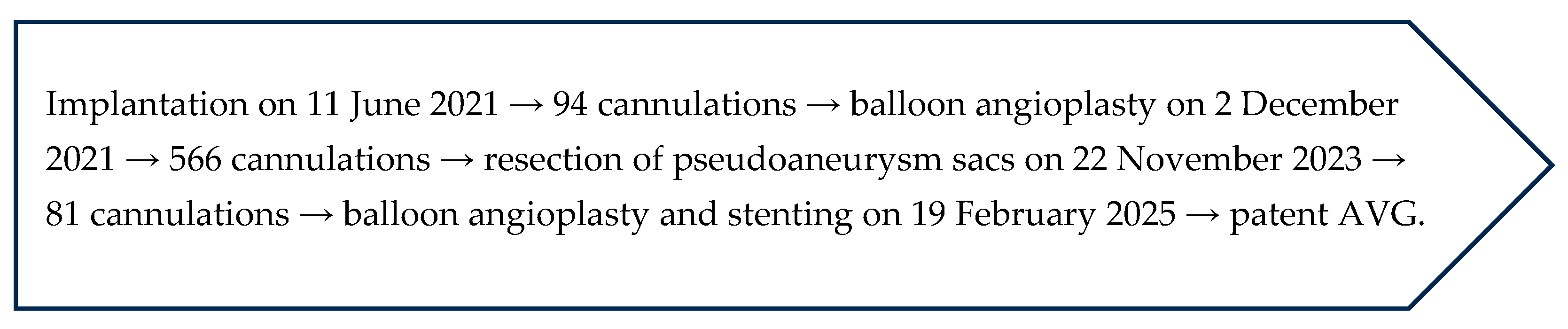

2.2. Case 2

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, E.; Ethier, I.; Cho, Y.; Htay, H.; Arruebo, S.; Caskey, F.J.; Damster, S.; Donner, J.A.; Jha, V.; Levin, A.; et al. Dialysis Outcomes Across Countries and Regions: A Global Perspective From the International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 2410–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.K.; Okpechi, I.G.; Osman, M.A.; Cho, Y.; Htay, H.; Jha, V.; Wainstein, M.; Johnson, D.W. Epidemiology of Haemodialysis Outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.K.; Haddad, N.J.; Vachharajani, T.J.; Asif, A. Innovations in Vascular Access for Hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besarab, A.; Kumbar, L. How Arteriovenous Grafts Could Help to Optimize Vascular Access Management. Semin. Dial. 2018, 31, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.S. Barriers to Optimal Vascular Access for Hemodialysis. Semin. Dial. 2020, 33, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allon, M.; Imrey, P.B.; Cheung, A.K.; Radeva, M.; Alpers, C.E.; Beck, G.J.; Dember, L.M.; Farber, A.; Greene, T.; Himmelfarb, J.; et al. Relationships Between Clinical Processes and Arteriovenous Fistula Cannulation and Maturation: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbert, R.J.; Nicholson, G.; Nordyke, R.J.; Pilgrim, A.; Niklason, L. Patency of EPTFE Arteriovenous Graft Placements in Hemodialysis Patients: Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Kidney360 2020, 1, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaishi, A.A.; Oliver, M.J.; Thomas, S.M.; Lok, C.E.; Zhang, J.C.; Garg, A.X.; Kosa, S.D.; Quinn, R.R.; Moist, L.M. Patency Rates of the Arteriovenous Fistula for Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 63, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.L.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Roetker, N.S.; Hart, A.; Knapp, C.D.; Ku, E.; Powe, N.R.; et al. US Renal Data System 2024 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2025, 85, A8–A11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jaishi, A.A.; Liu, A.R.; Lok, C.E.; Zhang, J.C.; Moist, L.M. Complications of the Arteriovenous Fistula: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1839–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorzaat, B.M.; Janmaat, C.J.; Van Der Bogt, K.E.A.; Dekker, F.W.; Rotmans, J.I. Patency Outcomes of Arteriovenous Fistulas and Grafts for Hemodialysis Access: A Trade-Off between Nonmaturation and Long-Term Complications. Kidney360 2020, 1, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankers, P.Y.W.; Harmsen, M.C.; Brouwer, L.A.; Van Luyn, M.J.A.; Meijer, E.W. A Modular and Supramolecular Approach to Bioactive Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbesma, R.P.; Beijer, F.H.; Brunsveld, L.; Folmer, B.J.B.; Hirschberg, J.H.K.K.; Lange, R.F.M.; Lowe, J.K.L.; Meijer, E.W. Reversible Polymers Formed from Self-Complementary Monomers Using Quadruple Hydrogen Bonding. Science 1997, 278, 1601–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mes, T.; Serrero, A.; Bauer, H.S.; Cox, M.A.J.; Bosman, A.W.; Meijer, E.W. Supramolecular Polymer Materials Bring Restorative Heart Valve Therapy to Patients. Mater. Today 2022, 52, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, M.; De Letter, J.; Krievins, D.; Jushinskis, J.; D’Haeninck, A.; Rucinskas, K.; Miglinas, M.; Baltrunas, T.; Nauwelaers, S.; Schoen, F.J.; et al. Endogenous Tissue Restoration in a Hemodialysis Conduit: Performance and Safety after 1-Year of Follow-Up. J. Vasc. Access 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, C.E.; Huber, T.S.; Lee, T.; Shenoy, S.; Yevzlin, A.S.; Abreo, K.; Allon, M.; Asif, A.; Astor, B.C.; Glickman, M.H.; et al. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Vascular Access: 2019 Update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, S1–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.T.; Blankestijn, P.J.; Dember, L.M.; Gallieni, M.; Harris, D.C.H.; Lok, C.E.; Mehrotra, R.; Stevens, P.E.; Wang, A.Y.M.; Cheung, M.; et al. Dialysis Initiation, Modality Choice, Access, and Prescription: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravani, P.; Palmer, S.C.; Oliver, M.J.; Quinn, R.R.; MacRae, J.M.; Tai, D.J.; Pannu, N.I.; Thomas, C.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Craig, J.C.; et al. Associations between Hemodialysis Access Type and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacson, E.; Lazarus, J.M.; Himmelfarb, J.; Ikizler, T.A.; Hakim, R.M. Balancing Fistula First With Catheters Last. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2007, 50, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Liu, K.; Luo, X. Risk Factors for Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in Hemodialysis Patients: A Retrospective Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeckova, J.; Bachleda, P.; Utikal, P.; Jarosciakova, J.; Orsag, J. Arteriovenous Grafts’ Types of Indications and Their Infection Rate. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 69, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhuidese, I.J.; Orandi, B.J.; Nejim, B.; Malas, M. Utilization, Patency, and Complications Associated with Vascular Access for Hemodialysis in the United States. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidli, J.; Widmer, M.K.; Basile, C.; de Donato, G.; Gallieni, M.; Gibbons, C.P.; Haage, P.; Hamilton, G.; Hedin, U.; Kamper, L.; et al. Editor’s Choice—Vascular Access: 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 55, 757–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozzi, M.; De Letter, J.; Krievins, D.; Jushinskis, J.; D’Haeninck, A.; Rucinskas, K.; Miglinas, M.; Baltrunas, T.; Nauwelaers, S.; De Vriese, A.S.; et al. First-in-Human Feasibility Study of the AXess Graft (AXess-FIH): 6-Month Results. J. Vasc. Access 2024, 26, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitkauskaitė, M.; Rimševičius, L.; Girčius, R.; Cox, M.A.J.; Miglinas, M. Four-Year Outcomes of aXess Arteriovenous Conduit in Hemodialysis Patients: Insights from Two Case Reports of the aXess FIH Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8768. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248768

Vitkauskaitė M, Rimševičius L, Girčius R, Cox MAJ, Miglinas M. Four-Year Outcomes of aXess Arteriovenous Conduit in Hemodialysis Patients: Insights from Two Case Reports of the aXess FIH Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8768. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248768

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitkauskaitė, Monika, Laurynas Rimševičius, Rokas Girčius, Martijn A. J. Cox, and Marius Miglinas. 2025. "Four-Year Outcomes of aXess Arteriovenous Conduit in Hemodialysis Patients: Insights from Two Case Reports of the aXess FIH Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8768. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248768

APA StyleVitkauskaitė, M., Rimševičius, L., Girčius, R., Cox, M. A. J., & Miglinas, M. (2025). Four-Year Outcomes of aXess Arteriovenous Conduit in Hemodialysis Patients: Insights from Two Case Reports of the aXess FIH Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8768. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248768