Lean Management in Medium-Sized Oral Cavity Defect Reconstruction: Facial Artery Musculomucosal Flaps Versus Free Flaps

Abstract

1. Introduction

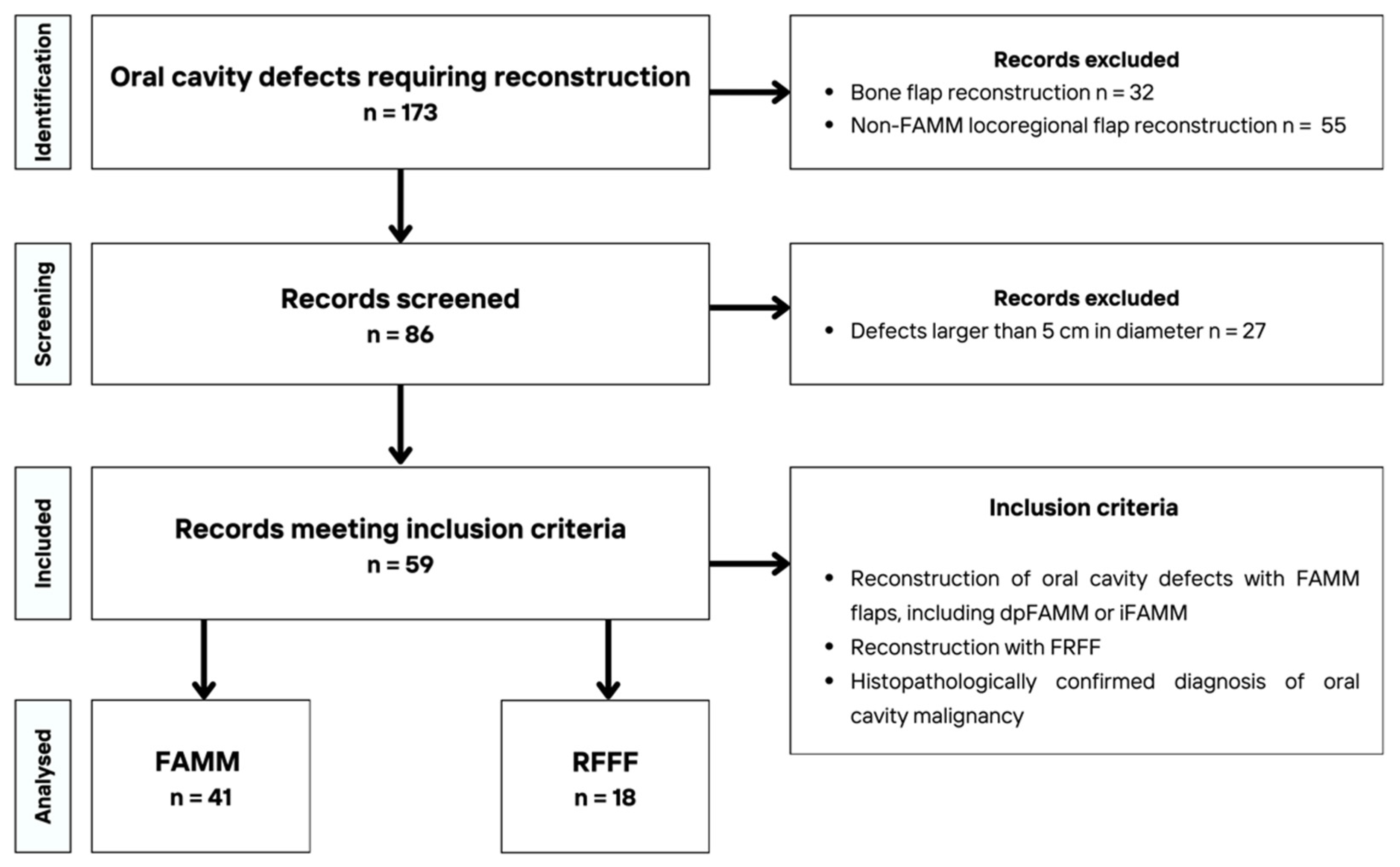

2. Materials and Methods

- Operating room (OR) cost per hour: 3500 PLN = 972 USD for one-team surgery (FAMM flap); 4600 PLN = 1278 USD for two-team surgery (free flap).

- Ward hospitalization cost per day: 1900 PLN = 528 USD per day.

- ICU hospitalization cost per day: 5600 PLN = 1556 USD per day.

3. Results

- Speech outcomes

- 100—Speech fully intelligible to all listeners.

- 75—Speech intelligible to most listeners; mild articulation disturbances present.

- 50—Speech intelligible only to persons familiar with the patient, requires listener concentration.

- 25—Speech intelligible only to close family members or caregivers.

- 0—Speech unintelligible or absence of verbal communication ability.

- Dietary outcomes

- 100—Normal diet without restrictions.

- 75—Able to eat most solid foods; avoids some difficult-to-chew items (e.g., tough meat).

- 50—Soft or semi-liquid (pureed) diet.

- 25—Limited to oral fluid intake only.

- 0—Unable to take food orally—fed via tube (gastrostomy).

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| FAMM | Facial artery musculomucosal flap |

| RFFF | Radial forearm free flap |

| dpFAMM | Double pedicled facial artery musculomucosal flap |

| iFAMM | Island facial artery musculomucosal flap |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| SND | Selective neck dissection |

| MRND | Modified radical neck dissection |

| ALT | Anterolateral thigh flap |

| NOS | Not otherwise specified |

| FCFF | Fasciocutaneous free flap |

| USD | United States dollars |

| OR | Operating room |

| CAD | Canadian dollars |

References

- Al-Moraissi, E.A.; Alkhutari, A.S.; de Bree, R.; Kaur, A.; Al-Tairi, N.H.; Pérez-Sayáns, M. Management of clinically node-negative early-stage oral cancer: Network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 53, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michcik, A.; Polcyn, A.; Sikora, M.; Wach, T.; Garbacewicz, Ł.; Drogoszewska, B. Oral squamous cell carcinoma—Do we always need elective neck dissection? Evaluation of clinicopathological factors of greatest prognostic significance: A cross-sectional observational study. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1203439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontarz, M.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G.; Zapała, J.; Czopek, J.; Lazar, A.; Tomaszewska, R. Proliferative index activity in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Indication for postoperative radiotherapy? Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urken, M.L.; Moscoso, J.F.; Lawson, W.; Biller, H.F. A Systematic Approach to Functional Reconstruction of the Oral Cavity Following Partial and Total Glossectomy. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 1994, 120, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R. Reconstruction of the oral cavity; past, present and future. Oral Oncol. 2020, 108, 104683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lis, E.; Michalik, W.; Bargiel, J.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Marecik, T.; Szczurowski, P.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G.; Dubrowski, A.; Gontarz, M. Reconstruction of the Oral Cavity Using Facial Vessel-Based Flaps—A Narrative Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganath, K.; Jalisi, S.; Naples, J.; Gomez, E. Comparing outcomes of radial forearm free flaps and anterolateral thigh free flaps in oral cavity reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2022, 135, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannelli, G.; Arcuri, F.; Agostini, T.; Innocenti, M.; Raffaini, M.; Spinelli, G. Classification of tongue cancer resection and treatment algorithm. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaad, O.; Al-Dewiri, R.; Kasht, L.; Qaddumi, B.; Ayyad, M. Adopting Lean Management in Quality of Services, Cost Containment, and Time Management. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2022, 23, 2835–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, R.M.; Shuman, A.G.; Feiner, S.; McGonegal, A.K.; Heidel, N.; Duck, M.; McLean, S.A.; Billi, J.E.; Healy, D.W.; Bradford, C.R. Lean management in academic surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012, 214, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagge, E.P.; Thirumoorthi, A.S.; Lenart, J.; Garberoglio, C.; Mitchell, K.W. Improving operating room efficiency in academic children’s hospital using Lean Six Sigma methodology. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 52, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- List, M.A.; Ritter-Sterr, C.; Lansky, S.B. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer 1990, 66, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean Thinking—Banish Waste and Create Wealth in your Corporation. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1997, 48, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liker, J.K. Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 330. [Google Scholar]

- Tomashev, R.; Alshiek, J.; Shobeiri, S.A. Improving the Operating Room Efficiency through Communication and Lean Principles. In The New Science of Medicine & Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, J.S.; Berry, L.L. The Promise of Lean in Health Care. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, E.W.; Singh, S.; Cheung, D.S.; Wyatt, C.C.; Nugent, A.S. Application of Lean Manufacturing Techniques in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2009, 37, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radnor, Z. Evaluation of the Lean Approach to Business Management and Its Use in the Public Sector; Scottish Executive: Edinburgh, UK, 2006; p. 137.

- Kim, C.S.; Spahlinger, D.A.; Kin, J.M.; Billi, J.E. Lean health care: What can hospitals learn from a world-class automaker? J. Hosp. Med. 2006, 1, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, T.; Xie, L. Facial artery musculomucosal flap in head and neck reconstruction: A systematic review. Head Neck 2015, 37, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontarz, M.; Bargiel, J.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Marecik, T.; Szczurowski, P.; Zapała, J.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. Extended, double-pedicled facial artery musculomucosal (Dpfamm) flap in tongue reconstruction in edentulous patients: Preliminary report and flap design. Medicina 2021, 57, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, O.; Vaira, L.A.; Biglio, A.; Gobbi, R.; Piombino, P.; De Riu, G. Rational and simplified nomenclature for buccinator myomucosal flaps. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 21, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontarz, M.; Bargiel, J.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Marecik, T.; Szczurowski, P.; Zapała, J.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. Feasibility of dpFAMM flap in tongue reconstruction after facial vessel ligation and radiotherapy—Case presentation. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soutar, D.S.; Scheker, L.R.; Tanner, N.S.B.; McGregor, I.A. The radial forearm flap: A versatile method for intra-oral reconstruction. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1983, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Chardon, V.M.; Balaguer, T.; Chignon-Sicard, B.; Riah, Y.; Ihrai, T.; Dannan, E.; Lebreton, E. The radial forearm free flap: A review of microsurgical options. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2009, 62, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Oles, N.; Reiche, E.; Kim, R.; Landford, W.; Eisenbeis, L.; Noyes, M.; Schuster, C.R.; Parisi, M.; Rahmayanti, S.; et al. Early Penile and Donor Site Sensory Outcomes After Innervated Radial Forearm Free Flap Phalloplasty: A Pilot Prospective Study. Microsurgery 2024, 44, e31228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’aRpa, S.; Cillino, M.; Mazzucco, W.; Rossi, M.; Mazzola, S.; Moschella, F.; Cordova, A. An algorithm to improve outcomes of radial forearm flap donor site. Acta Chir. Belg. 2018, 118, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, P.A.; Davis, S.; Sweedan, A.O.; ElSabbagh, A.M.; Fernandes, R.P. Volumetric changes in post hemiglossectomy reconstruction with anterolateral thigh free flap versus radial forearm free flap. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 53, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydarfar, J.A.; Patel, U.A. Submental island pedicled flap vs. radial forearm free flap for oral reconstruction: Comparison of outcomes. Arch. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2011, 137, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Fan, C.; Pecchia, B.; Rosenberg, J.D. Submental island flap vs. free tissue transfer in oral cavity reconstruction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 2020, 42, 2155–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, D.; Phillips, T.; Rigby, M.; Hart, R.; Taylor, M.; Trites, J. Submental island flap reconstruction reduces cost in oral cancer reconstruction compared to radial forearm free flap reconstruction: A case series and cost analysis. J. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2016, 45, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittitrai, P.; Ruenmarkkaew, D.; Klibngern, H. Pedicled Flaps versus Free Flaps for Oral Cavity Cancer Reconstruction: A Comparison of Complications, Hospital Costs, and Functional Outcomes. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 27, e32–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katna, R.; Girkar, F.; Tarafdar, D.; Bhosale, B.; Singh, S.; Agarwal, S.; Deshpande, A.; Kalyani, N. Pedicled Flap vs. Free Flap Reconstruction in Head and Neck Cancers: Clinical Outcome Analysis from a Single Surgical Team. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 12, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louizakis, A.; Antoniou, A.; Kalaitsidou, I.; Tatsis, D. Free Tissue Transfer Versus Locoregional Flaps for the Reconstruction of Small and Moderate Defects in the Head and Neck Region: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 154, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozin, E.D.; Sethi, R.K.; Herr, M.; Shrime, M.G.; Rocco, J.W.; Lin, D.; Deschler, D.G.; Emerick, K.S. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes between the Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap and Fasciocutaneous Free Flap. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Cao, G.; Dong, Z. Pedicled Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap Versus Free Radial Forearm Flap for Tongue Reconstruction Following Hemiglossectomy. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, e527–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsing, C.-Y.; Wong, Y.-K.; Wang, C.P.; Wang, C.-C.; Jiang, R.-S.; Chen, F.-J.; Liu, S.-A. Comparison between free flap and pectoralis major pedicled flap for reconstruction in oral cavity cancer patients—A quality of life analysis. Oral Oncol. 2011, 47, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, Y.; El Bedoui, S.; Penel, N.; Ton Van, J.; Fournier, C.; Lefebvre, J.L. The free vascularized flap and the pectoralis major pedicled flap options: Comparative results of reconstruction of the tongue. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.-T.; Wen, Y.-W.; Lee, S.-R.; Ng, S.-H.; Liu, T.-W.; Tsai, S.-T.; Tsai, M.-H.; Lin, J.-C.; Chien, C.-Y.; Lou, P.-J.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Taiwanese Patients with Resected Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma Who Underwent Reconstruction with Free Versus Local Flaps. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Rahal, A.; Bissada, E.; Christopoulos, A.; Guertin, L.; Ayad, T. Reconstruction of medium-size defects of the oral cavity: Radial forearm free flap vs. facial artery musculo-mucosal flap. J. Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2021, 50, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Naveen, B.S.; Mohan, M.T.; Tharayil, J. Comparison of islanded facial artery myomucosal flap with fasciocutaneous free flaps in the reconstruction of lateral oral tongue defects. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaira, L.A.; Massarelli, O.; Polesel, J.; Ferri, A.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Cuéllar, I.N.; Consorti, G.; Cirignaco, G.; Cucurullo, M.; Salzano, G.; et al. Oncologic Safety of Facial-Vessel–Based Buccinator Myomucosal Flaps for Tongue and Oral Floor Reconstruction: A Retrospective Multicenter Case–Control Study. Head Neck 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelke, K.H.; Pawlak, W.; Gerber, H.; Leszczyszyn, J. Head and neck cancer patients’ quality of life. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 23, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total number of patients (n, %) | 59 (100%) |

| Age, [years], mean (SD) | 64.00 (±12.67) |

| Gender (n, %) | |

| Female (n, %) | 27 (45.76%) |

| Male (n, %) | 32 (54.24%) |

| BMI [kg/m2], mean (SD) | 25.02 (±4.03) |

| Smoking history (n, %) | |

| Non-smoker | 26 (44.07%) |

| Smoker | 33 (55.93%) |

| Alcohol consumption (n, %) | |

| Non-drinker | 43 (77.97%) |

| Occasional drinker (less than 3 times per week) | 12 (20.34%) |

| Alcohol dependence syndrome | 4 (6.78%) |

| Histopathological diagnosis (n, %) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 47 (79.66%) |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 6 (10.17%) |

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 5 (8.48%) |

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 1 (1.69%) |

| Lesion location (n, %) | |

| Tongue | 14 (23.73%) |

| Floor of the mouth | 8 (13.56%) |

| Both tongue and floor of the mouth | 12 (20.34%) |

| Hard or soft palate | 15 (25.42%) |

| Retromolar triangle and gingiva | 10 (16.95%) |

| Lesion site (n, %) | |

| Right | 32 (54.24%) |

| Left | 20 (33.90%) |

| Midline | 7 (11.86%) |

| Lesion measurement [mm], mean (SD) | 24.91 (±11.73) |

| Surgical technique (n, %) | |

| FAMM flap | 41 (69.49%) |

| dpFAMM | 30 (73.17%) |

| iFAMM | 11 (26.83%) |

| Free flap | 18 (30.51%) |

| RFFF | 18 (100.00%) |

| Type of procedure (n, %) | |

| Primary reconstruction | 49 (83.05%) |

| Secondary reconstruction | 10 (16.95%) |

| Study Group | FAMM | FREE FLAPS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients (n, %) | 41 (100%) | 18 (100%) | - |

| Age, [years], mean (SD) | 65.32 (±13.21) | 61.82 (±10.79) | 0.123 |

| Gender (n, %) | 0.07 | ||

| Female (n, %) | 22 (53.66%) | 5 (27.78%) | |

| Male (n, %) | 19 (46.34%) | 13 (72.22%) | |

| BMI [kg/m2], mean (SD) | 24.75 (±4.27) | 26.54 (±3.43) | 0.736 |

| Comorbidities count (n, %) | 0.07 | ||

| One or less | 22 (53.66%) | 5 (27.78%) | |

| More than one | 19 (46.34%) | 13 (72.22%) | |

| Smoking history (n, %) | 0.038 | ||

| Non-smoker | 21 (51.22%) | 5 (27.78%) | |

| Smoker | 20 (48.78%) | 13 (72.22%) | |

| Alcohol consumption (n, %) | 0.032 | ||

| Non-drinker | 29 (70.73%) | 14 (77.78%) | |

| Occasional drinker (<3 times/week) | 11 (26.83%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Alcohol dependence syndrome | 1 (2.44%) | 3 (16.67%) | |

| Histopathological diagnosis (n, %) | - | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 19 (46.34%) | 18 (100%) | |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 2 (4.88%) | ||

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 5 (12.20%) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma NOS | 1 (2.44%) | ||

| Lesion location (n, %) | <0.001 | ||

| Tongue | 9 (21.95%) | 5 (27.78%) | |

| Floor of the mouth | 6 (14.63%) | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Both tongue and floor of the mouth | 9 (21.95%) | 3 (16.67%) | |

| Hard or soft palate | 15 (36.59%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| Retromolar triangle and gingiva area | 2 (4.88%) | 8 (44.44%) | |

| Lesion site (n, %) | 0.425 | ||

| Right | 24 (58.64%) | 8 (44.44%) | |

| Left | 13 (31.71%) | 7 (38.89%) | |

| Midline | 4 (9.76%) | 3 (16.67%) | |

| Lesion measurement [mm], mean (SD) | 23.53 (±12.39) | 28.52 (±9.53) | 0.148 |

| Type of procedure (n, %) | 0.141 | ||

| Primary reconstruction | 36 (87.80%) | 13 (72.22%) | |

| Secondary reconstruction | 5 (12.20%) | 5 (27.78%) |

| Procedure Type | FAMM FLAPS | FREE FLAPS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of the surgical procedure [min], mean (SD) | 196.71 (±94.92) | 427.11 (±129.76) | <0.001 |

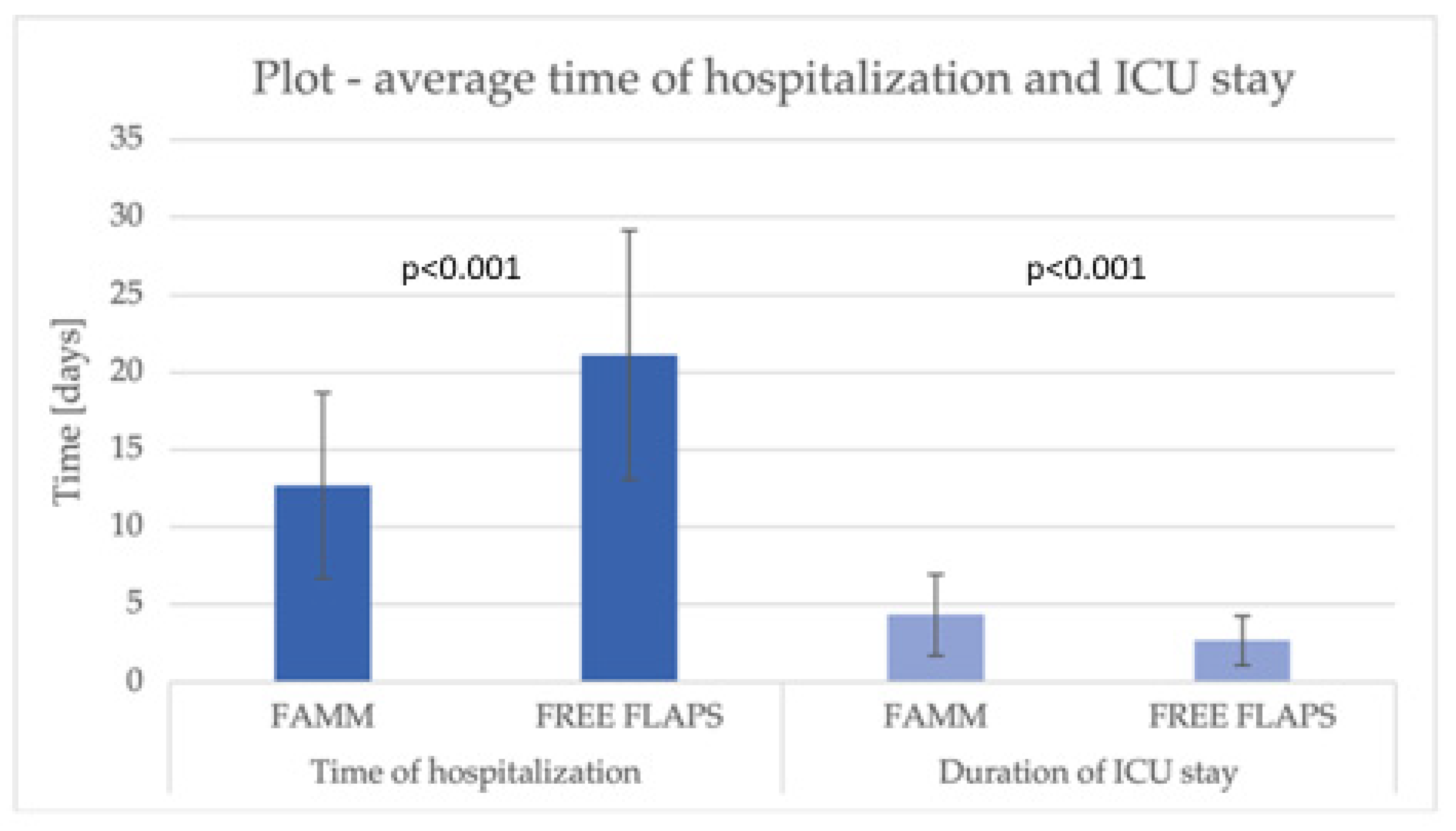

| Time of hospitalization [days], mean (SD) | 12.68 (±6.00) | 21.11 (±8.04) | <0.001 |

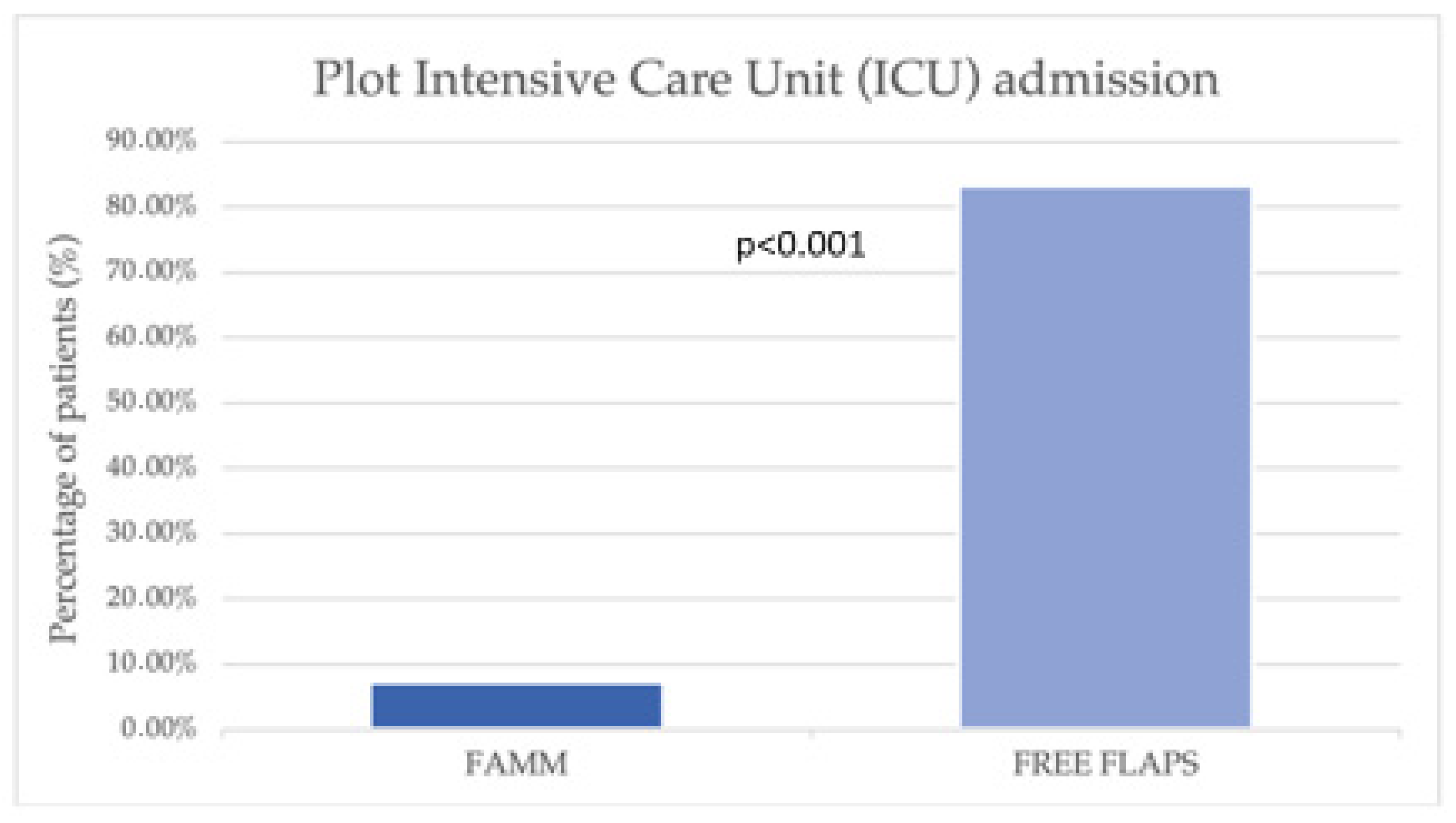

| Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission (n, %) | 3 (7.32%) | 15 (83.33%) | <0.001 |

| Duration of ICU stay [days], mean (SD) | 4.33 (±2.62) | 2.67 (±1.59) | <0.001 |

| Tracheostomy performed (n, %) | 3 (7.32%) | 3 (16.67%) | 0.357 |

| Postoperative enteral nutrition (n, %) | 1 (2.44%) | 3 (16.67%) | 0.203 |

| Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy | 1 (2.44%) | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Surgical gastrostomy | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Resection type (n, %) | 0.684 | ||

| R0 | 36 (87.80%) | 14 (77.78%) | |

| R1 | 5 (12.20%) | 4 (22.22%) | |

| Neck lymph node dissection (n, %) | 27 (65.85%) | 16 (88.89%) | 0.111 |

| unilateral | 5 (12.20%) | 1 (5.56%) | 0.386 |

| bilateral | 22 (53.66%) | 15 (83.33%) | |

| Type of ipsilateral procedure (n, %) | 0.702 | ||

| SND | 26 (63.41%) | 15 (83.33%) | |

| MRND | 1 (2.44%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Type of contralateral procedure (n, %) | - | ||

| SND | 22 (53.66%) | 15 (83.33%) | |

| MRND | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Radiotherapy (n, %) | 0.268 | ||

| Postoperative | 18 (43.90%) | 12 (66.67%) | |

| Preoperative | 5 (12.20%) | 2 (11.11%) | |

| Complications occurrence (n, %) | 8 (19.51%) | 7 (38.89%) | 0.116 |

| Wound dehiscence | 6 (14.63%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Wound hematoma | 2 (4.88%) | 1 (5.56%) | |

| Partial flap necrosis | 0 (0.00%) | 4 (22.22%) | |

| Complete flap necrosis | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (5.56%) |

| Study Group | FAMM | FREE FLAPS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech PSS-HN score | |||

| Median [IQR] | 75.00 [56.25–100.00] | 75.00 [75.00–93.75] | 0.534 |

| Nutrition PSS-HN score | |||

| Median [IQR] | 75.00 [50.00–100.00] | 50.00 [50.00–100.00] | 0.243 |

| Study Group | FAMM | FREE FLAPS | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up time [months], mean (SD) | 11.03 (±12.67) | 10.75 (±9.51) | 0.719 |

| Local recurrences (n, %) | 2 (4.88%) | 4 (22.22%) | 0.643 |

| Time to local recurrence, [months], mean (SD) | 19.00 (±19.80) | 7.25 (±2.50) | |

| Nodal recurrences (n, %) | 2 (4.88%) | 4 (22.22%) | 0.064 |

| Time to nodal recurrence, [months], mean (SD) | 1.50 (±0.71) | 4.60 (±2.88) | |

| Need for flap modeling (n, %) | 20 (48.78%) | 2 (11.11%) | 0.008 |

| Disease specific survival (n, %) | 3 (7.32%) | 2 (11.11%) | 0.248 |

| Time to death [months], mean (SD) | 6.50 (±4.27) | 10.00 (±1.41) |

| Results | Joseph et al., 2020 [42] | Ibrahim et al., 2021 [41] | Gontarz et al., 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 40 (20 iFAMM, 20 FCFF) | 31 (13 FAMM, 18 RFFF) | 59 (41 FAMM, 18 RFFF) |

| Mean age [years] | iFAMM 51.5 vs. FCFF 44.7 (p = 0.38) | FAMM 66 vs. RFFF 62 (p = 0.306) | FAMM 66 vs. RFFF 61.8 (p = 0.123) |

| Female/male ratio | not given (majority male) | 5:8 in FAMM; 8:10 in RFFF | 12:10 in FAMM, 4:10 in RFFF |

| Surgical method | islanded facial artery myomucosal (iFAMM) flap; fasciocutaneous free flap (FCFF) | FAMM RFFF | FAMM RFFF |

| Operating time (mean) | iFAMM 56.5 min vs. FCFF 150.5 min (p < 0.001) | FAMM 432 min vs. RFFF 534 min (p= 0.002) | FAMM 196.7 min vs RFFF 427.1 min, (p < 0.001) |

| Hospital stay (mean) | iFAMM 7.5 days vs. FCFF 9.4 days (p = 0.45) | No significant difference (p = 0.717) | FAMM 12.7 days vs. RFFF 21.1 days (p < 0.001) |

| ICU stay (mean) | iFAMM 1-day vs. FCFF 3.2 days (p < 0.001) | Not specified (rare ICU use for FAMM) | ICU admission significantly lower in FAMM group (7.3% vs. 83.3%, p < 0.001); However, the duration of ICU stay marginally longer in FAMM (4.3 vs. 2.7 days, p < 0.001) |

| Need for tracheostomy | iFAMM 0 vs. FCFF 14 cases (p < 0.001) | Both groups 100% tracheostomy | Tracheostomy performed in the minority of patients in both groups |

| Complications | iFAMM 5 minor complications vs. FCFF 5 minor complications, no flap loss in both groups | FAMM 1 minor (7.7%) vs. RFFF 15 complications in 10 patients (55%) (p = 0.008) | FAMM 8 minor complications (19.5%) vs. RFFF 7 minor complications (38.9%) in (p = 0.116). Complete flap necrosis in 1 RFFF patient, no flaps loss in FAMM group |

| Functional outcomes | Speech & swallowing similar (p > 0.1); Esthetics better for iFAMM (VAS 8.4 vs. 6.0) | Speech & swallowing similar (p > 0.05) | Speech & swallowing similar (p > 0.05) |

| Economic cost | FCFF ≈ 30% more expensive than iFAMM | FAMM CAD 24,188 vs. RFFF CAD 35,247 (–31% difference, p = 0.109) | FAMM USD 10,404 vs. RFFF USD 23,607 (–56% difference, p < 0.001) |

| Overall conclusion | The iFAMM flap was associated with shorter operative and ICU stay times, reduced hospitalization time, and greater cost efficiency, while providing superior esthetic outcomes and lower donor site morbidity. | FAMM flaps are associated with lower costs, shorter OR time, similar functional outcomes and a tendency to lower complication rates. | FAMM flap constitutes a reliable and cost-effective option, with satisfactory functional and esthetic outcomes while reducing operative time, hospitalization, and overall treatment costs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gontarz, M.; Lis, E.; Biel, K.; Bargiel, J.; Gąsiorowski, K.; Nelke, K.; Díaz Mirón, D.G.R.; Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. Lean Management in Medium-Sized Oral Cavity Defect Reconstruction: Facial Artery Musculomucosal Flaps Versus Free Flaps. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8760. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248760

Gontarz M, Lis E, Biel K, Bargiel J, Gąsiorowski K, Nelke K, Díaz Mirón DGR, Wyszyńska-Pawelec G. Lean Management in Medium-Sized Oral Cavity Defect Reconstruction: Facial Artery Musculomucosal Flaps Versus Free Flaps. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8760. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248760

Chicago/Turabian StyleGontarz, Michał, Emilia Lis, Konrad Biel, Jakub Bargiel, Krzysztof Gąsiorowski, Kamil Nelke, Dayel Gerardo Rosales Díaz Mirón, and Grażyna Wyszyńska-Pawelec. 2025. "Lean Management in Medium-Sized Oral Cavity Defect Reconstruction: Facial Artery Musculomucosal Flaps Versus Free Flaps" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8760. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248760

APA StyleGontarz, M., Lis, E., Biel, K., Bargiel, J., Gąsiorowski, K., Nelke, K., Díaz Mirón, D. G. R., & Wyszyńska-Pawelec, G. (2025). Lean Management in Medium-Sized Oral Cavity Defect Reconstruction: Facial Artery Musculomucosal Flaps Versus Free Flaps. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8760. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248760