Effects of Contrast Media on Renal Function Following Computed Tomography Prior to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

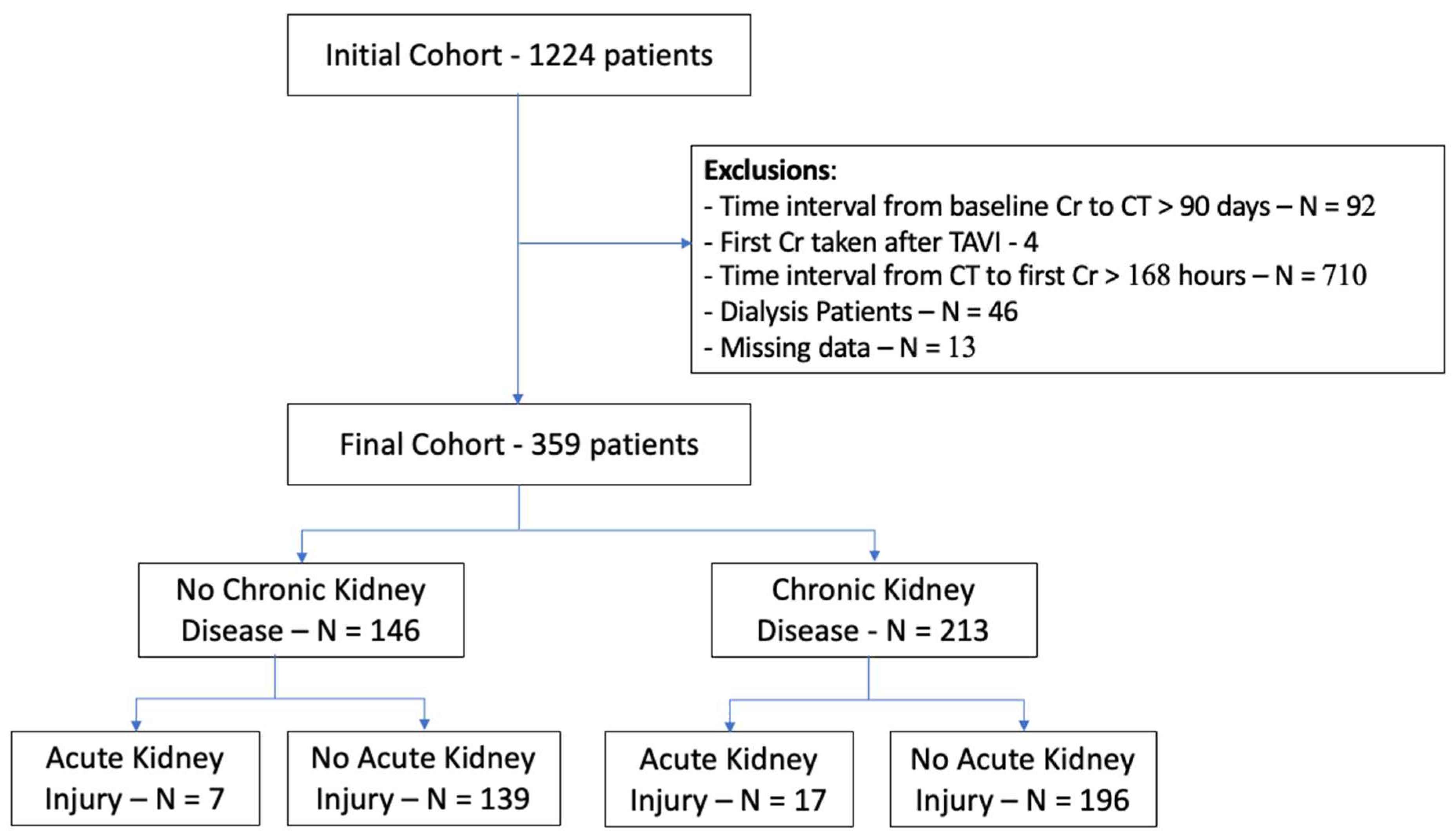

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Pre-TAVI

2.3. Clinical Data and Study Endpoint

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

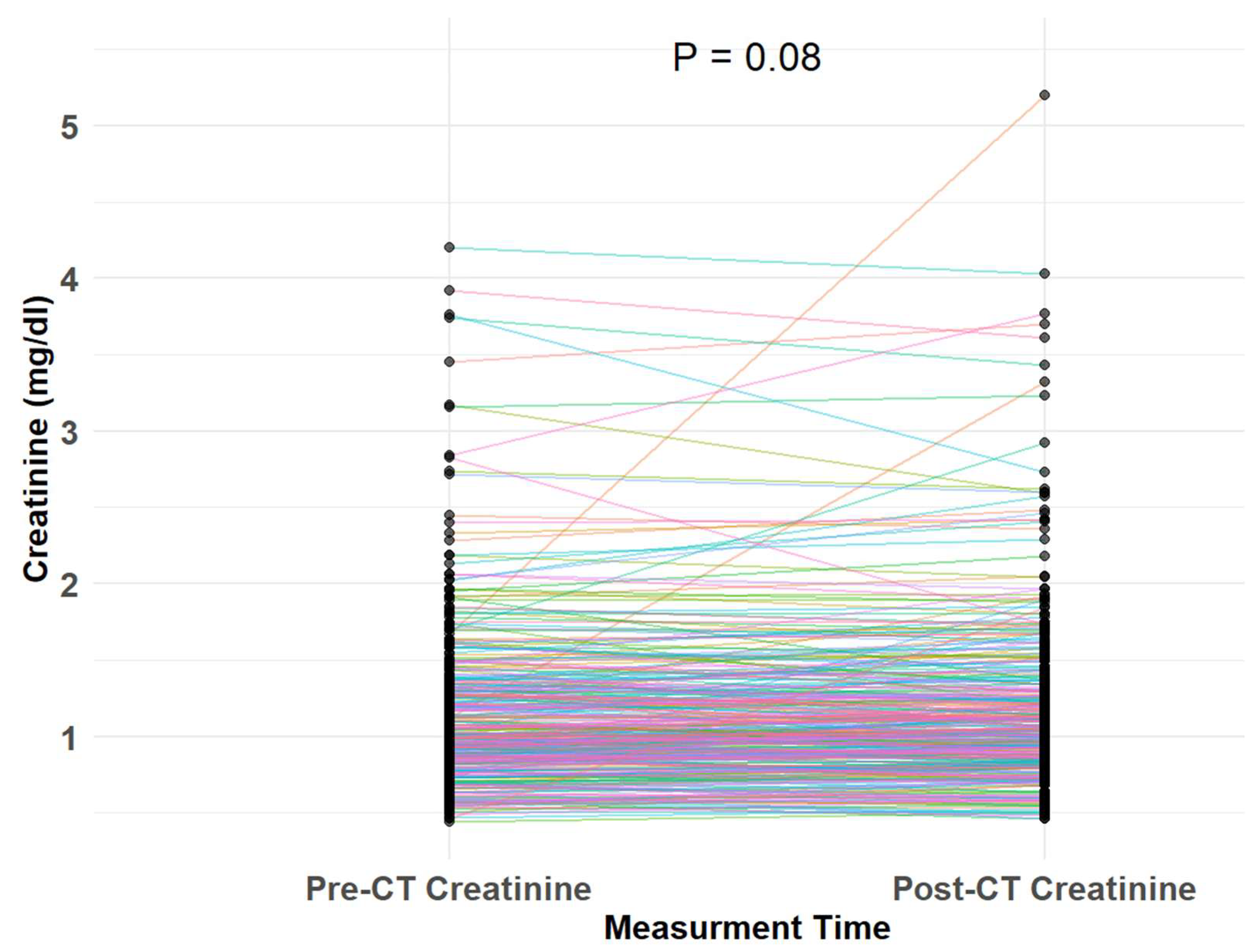

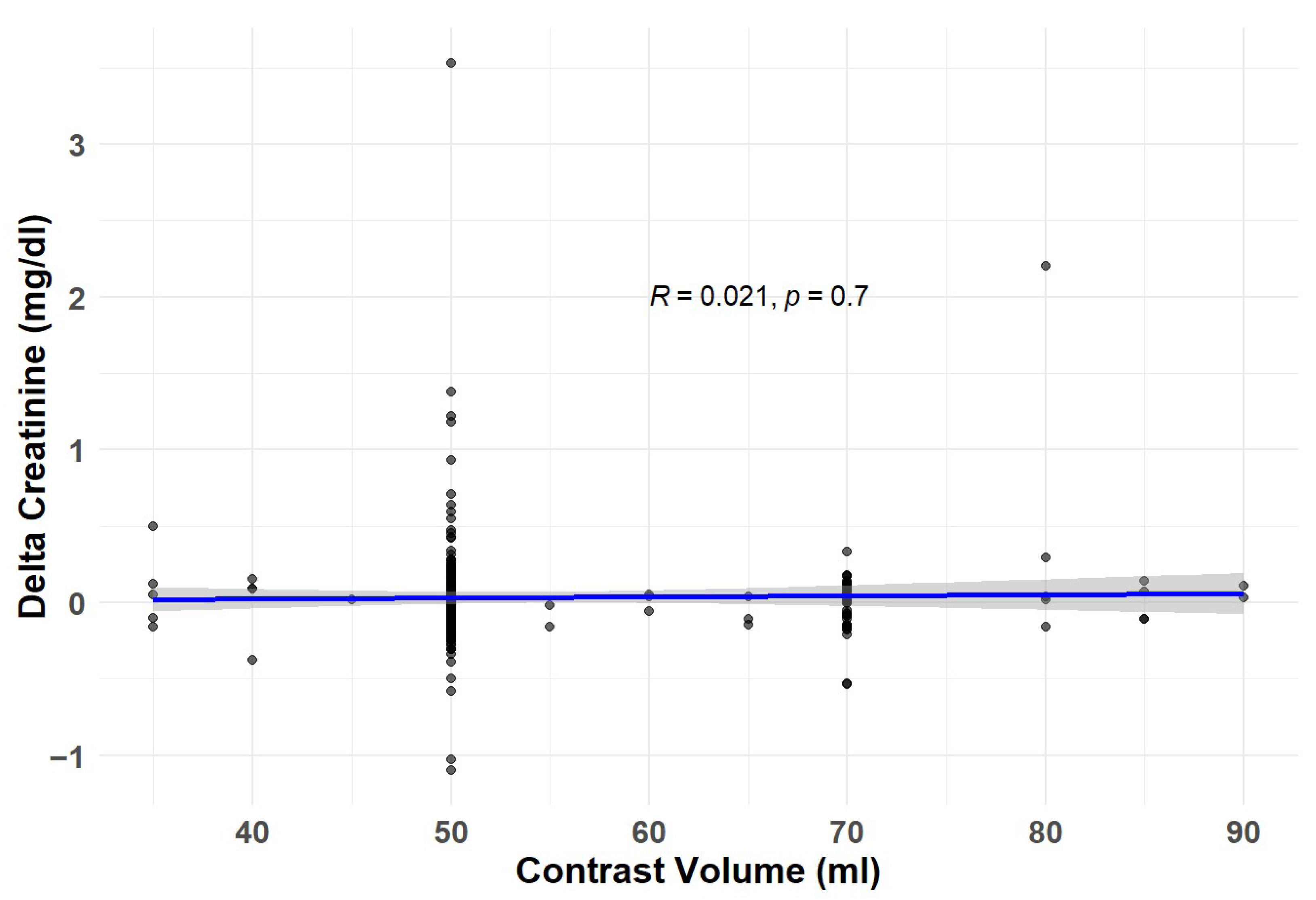

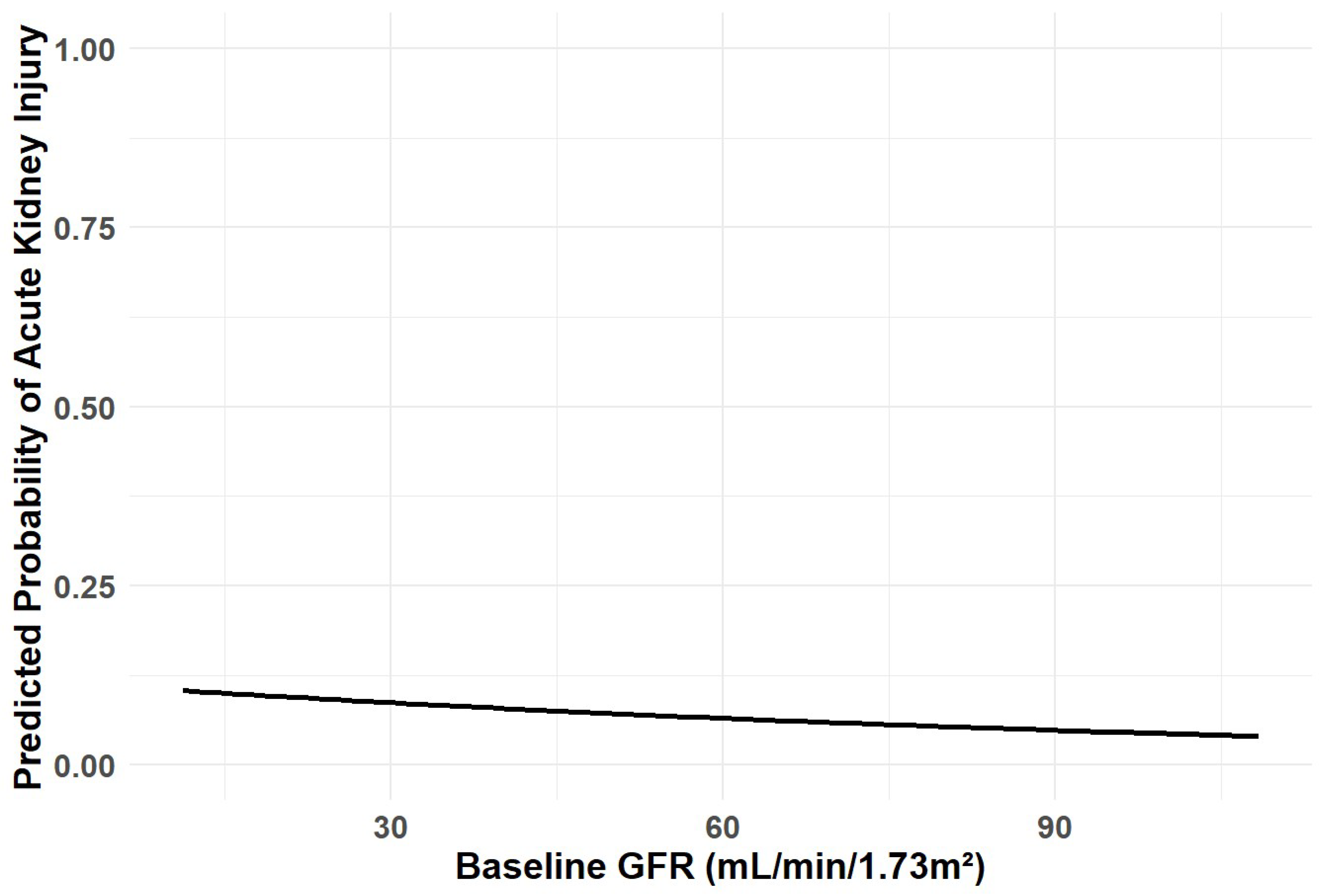

3.2. Study Endpoints

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Praz, F.; Borger, M.A.; Lanz, J.; Marin-Cuartas, M.; Abreu, A.; Adamo, M.; Marsan, N.A.; Barili, F.; Bonaros, N.; Cosyns, B.; et al. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the task force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4635–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, M.J.; Leon, M.B.; Thourani, V.H.; Makkar, R.; Kodali, S.K.; Russo, M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Malaisrie, S.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Pibarot, P.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes Filho, A.C.B.; Katz, M.; Campos, C.M.; Carvalho, L.A.; Siqueira, D.A.; Tumelero, R.T.; Portella, A.L.F.; Esteves, V.; Perin, M.A.; Sarmento-Leite, R.; et al. Impact of Acute Kidney Injury on Short- and Long-term Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 72, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanke, P.; Weir-McCall, J.R.; Achenbach, S.; Delgado, V.; Hausleiter, J.; Jilaihawi, H.; Marwan, M.; Nørgaard, B.L.; Piazza, N.; Schoenhagen, P.; et al. Computed Tomography Imaging in the Context of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI)/Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR): An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzberg, R.W.; Pabico, R.C.; Morris, T.W.; Hayakawa, K.; McKenna, B.A.; Panner, B.J.; Ventura, J.A.; Fischer, H.W. Effects of contrast media on renal function and subcellular morphology in the dog. Investig. Radiol. 1986, 21, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.H.; Cohan, R.H. Reducing the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy: A perspective on the controversies. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 192, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idée, J.M.; Bonnemain, B. Reliability of experimental models of iodinated contrast media-induced acute renal failure. From methodological considerations to pathophysiology. Investig. Radiol. 1996, 31, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsberg, R.P.; Dohad, S.Y.; Sheng, R. Iodixanol Peripheral CTA Study Investigator Panel. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) following intra-arterial administration of iodinated contrast media. J. Nephrol. 2010, 23, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moos, S.I.; Van Vemde, D.N.H.; Stoker, J.; Bipat, S. Contrast induced nephropathy in patients undergoing intravenous (IV) contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and the relationship with risk factors: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Radiol. 2013, 82, e387–e399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parfrey, P.S.; Griffiths, S.M.; Barrett, B.J.; Paul, M.D.; Genge, M.; Withers, J.; Farid, N.; McManamon, P.J. Contrast material-induced renal failure in patients with diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, or both. A prospective controlled study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooiman, J.; Le Haen, P.A.; Gezgin, G.; de Vries, J.-P.P.; Boersma, D.; Brulez, H.F.; Sijpkens, Y.W.; van der Molen, A.J.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Hamming, J.F.; et al. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and clinical outcomes after intra-arterial and intravenous contrast administration: Risk comparison adjusted for patient characteristics by design. Am. Heart J. 2013, 165, 793–799.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R.J.; McDonald, J.S.; Bida, J.P.; Carter, R.E.; Fleming, C.J.; Misra, S.; Williamson, E.E.; Kallmes, D.F. Intravenous contrast material-induced nephropathy: Causal or coincident phenomenon? Radiology 2013, 267, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KDIGO Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.S.; McDonald, R.J.; Comin, J.; Williamson, E.E.; Katzberg, R.W.; Murad, M.H.; Kallmes, D.F. Frequency of acute kidney injury following intravenous contrast medium administration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 2013, 267, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, A.; Aronson, D. Risk of Acute Kidney Injury after Intravenous Contrast Media Administration in Patients with Suspected Pulmonary Embolism: A Propensity-Matched Study. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 121, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aycock, R.D.; Westafer, L.M.; Boxen, J.L.; Majlesi, N.; Schoenfeld, E.M.; Bannuru, R.R. Acute Kidney Injury After Computed Tomography: A Meta-analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 71, 44–53.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochheim, D.; Schneider, V.S.; Schwarz, F.; Kupatt, C.; Lange, P.; Reiser, M.; Massberg, S.; Gutiérrez-Chico, J.-L.; Mehilli, J.; Becker, H.-C. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury after computed tomography prior to transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Clin. Radiol. 2014, 69, 1034–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, P.A.; Adam, A.; Becker, C.R.; Davidson, C.; Lameire, N.; Stacul, F.; Tumlin, J. Epidemiology and prognostic implications of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006, 98, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzberg, R.W.; Newhouse, J.H. Intravenous contrast medium-induced nephrotoxicity: Is the medical risk really as great as we have come to believe? Radiology 2010, 256, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratta, P.; Bozzola, C.; Quaglia, M. Pitfall in nephrology: Contrast nephropathy has to be differentiated from renal damage due to atheroembolic disease. J. Nephrol. 2012, 25, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Overall | NO-CKD | CKD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 359 | 146 | 213 | |

| Age, years (median [IQR]) | 81 (75–85) | 78 (73–84) | 82 (77–86) | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 159 (44.3) | 64 (43.8) | 95 (44.6) | 0.972 |

| Baseline eGFR (median [IQR]) | 57 (41–78) | 78 (72–87) | 45 (36–54) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease present, n (%) | 213 (59.3) | 0 (0.0) | 213 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| CKD stage distribution, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Stage G5 | 5 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Stage G4 | 30 (8.4) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (14.1) | |

| Stage G3b | 74 (20.6) | 0 (0.0) | 74 (34.7) | |

| Stage G3a | 82 (22.8) | 0 (0.0) | 82 (38.5) | |

| Stage G2 | 143 (39.8) | 123 (84.2) | 20 (9.4) | |

| Stage G1 | 25 (7.0) | 23 (15.8) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 325 (90.5) | 123 (84.2) | 202 (94.8) | 0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 215 (59.9) | 77 (52.7) | 138 (64.8) | 0.029 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 84 (23.4) | 35 (24.0) | 49 (23.0) | 0.932 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 94 (26.2) | 33 (22.6) | 61 (28.6) | 0.248 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 183 (51.0) | 79 (54.1) | 104 (48.8) | 0.381 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 334 (93.0) | 128 (87.7) | 206 (96.7) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 214 (59.6) | 86 (58.9) | 128 (60.1) | 0.907 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 161 (44.8) | 53 (36.3) | 108 (50.7) | 0.01 |

| ASA treatment, n (%) | 186 (51.8) | 77 (52.7) | 109 (51.2) | 0.854 |

| P2Y12 treatment, n (%) | 57 (15.9) | 16 (11) | 41 (19.2) | 0.05 |

| OAC treatment, n (%) | 207 (57.7) | 70 (47.9) | 137 (64.3) | 0.003 |

| RAASi treatment, n (%) | 138 (38.4) | 42 (28.8) | 96 (45.1) | 0.003 |

| Beta Blockers treatment, n (%) | 260 (72.4) | 93 (63.7) | 167 (78.4) | 0.003 |

| Statin treatment, n (%) | 281 (78.3) | 99 (67.8) | 182 (85.4) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Overall | NO-AKI | AKI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 359 | 335 | 24 | |

| Age, years (median [IQR]) | 80.73 [74.90, 85.28] | 80.68 [74.79, 84.98] | 81.51 [77.93, 87.09] | 0.275 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 159 (44.3) | 147 (43.9) | 12 (50.0) | 0.711 |

| Baseline eGFR, (median [IQR]) | 56.74 [41.37, 77.50] | 57.50 [41.87, 77.93] | 48.65 [40.20, 68.50] | 0.25 |

| Chronic kidney disease present, n (%) | 213 (59.3) | 196 (58.5) | 17 (70.8) | 0.331 |

| CKD stage distribution, n (%) | 0.612 | |||

| Stage G5 | 5 (1.4) | 5 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Stage G4 | 30 (8.4) | 26 (7.8) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Stage G3b | 74 (20.6) | 68 (20.3) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Stage G3a | 82 (22.8) | 77 (23.0) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Stage G2 | 143 (39.8) | 136 (40.6) | 7 (29.2) | |

| Stage G1 | 25 (7.0) | 23 (6.9) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 325 (90.5) | 303 (90.4) | 22 (91.7) | 1 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 215 (59.9) | 197 (58.8) | 18 (75.0) | 0.178 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 84 (23.4) | 77 (23.0) | 7 (29.2) | 0.659 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 94 (26.2) | 85 (25.4) | 9 (37.5) | 0.287 |

| Stroke/TIA, n (%) | 183 (51.0) | 173 (51.6) | 10 (41.7) | 0.464 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 334 (93.0) | 310 (92.5) | 24 (100.0) | 0.331 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 214 (59.6) | 196 (58.5) | 18 (75.0) | 0.169 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 161 (44.8) | 149 (44.5) | 12 (50.0) | 0.754 |

| ASA treatment, n (%) | 186 (51.8) | 169 (50.4) | 17 (70.8) | 0.086 |

| P2Y12 treatment, n (%) | 57 (15.9) | 54 (16.1) | 3 (12.5) | 0.857 |

| OAC treatment, n (%) | 207 (57.7) | 190 (56.7) | 17 (70.8) | 0.255 |

| RAASi treatment, n (%) | 138 (38.4) | 132 (39.4) | 6 (25) | 0.236 |

| Beta Blockers treatment, n (%) | 260 (72.4) | 240 (71.6) | 20 (83.3) | 0.317 |

| Statin treatment, n (%) | 281 (78.3) | 261 (77.9) | 20 (83.3) | 0.714 |

| Variable | Overall | NO-CKD | CKD | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 359 | 146 | 213 | |

| Any acute kidney injury, n (%) | 24 (6.7) | 7 (4.8) | 17 (8.0) | 0.331 |

| Contrast volume injected, mL (mean ± SD) | 54 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | 54 ± 10 | 0.255 |

| New dialysis within 30 days, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Mortality within one week of CT, n (%) | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.72 | 0.72–4.56 | 0.240 | 1.46 | 0.59–3.97 | 0.430 |

| Age (per year) | 1.04 | 0.98–1.10 | 0.223 | 1.02 | 0.97–1.09 | 0.432 |

| Male | 1.28 | 0.55–2.96 | 0.561 | 1.14 | 0.48–2.70 | 0.764 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2.13 | 0.87–5.99 | 0.119 | 2.00 | 0.80–5.72 | 0.159 |

| Contrast injected | 0.97 | 0.91–1.02 | 0.254 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.02 | 0.318 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Itelman, E.; Awesat, J.; Codner, P.; Aviv, Y.; Grinberg, T.; Abitbol, M.; Shafir, G.; Skalsky, K.; Shechter, A.; Kornowski, R.; et al. Effects of Contrast Media on Renal Function Following Computed Tomography Prior to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248754

Itelman E, Awesat J, Codner P, Aviv Y, Grinberg T, Abitbol M, Shafir G, Skalsky K, Shechter A, Kornowski R, et al. Effects of Contrast Media on Renal Function Following Computed Tomography Prior to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248754

Chicago/Turabian StyleItelman, Edward, Jenan Awesat, Pablo Codner, Yaron Aviv, Tzlil Grinberg, Merry Abitbol, Gideon Shafir, Keren Skalsky, Alon Shechter, Ran Kornowski, and et al. 2025. "Effects of Contrast Media on Renal Function Following Computed Tomography Prior to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248754

APA StyleItelman, E., Awesat, J., Codner, P., Aviv, Y., Grinberg, T., Abitbol, M., Shafir, G., Skalsky, K., Shechter, A., Kornowski, R., & Hamdan, A. (2025). Effects of Contrast Media on Renal Function Following Computed Tomography Prior to Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248754