Systemic Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels as a Predictor of Progression from Non-Proliferative to Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

2.2. Patient Cohorts and Exposure Definition

2.3. Propensity Score Matching

3. Outcomes

4. Results

4.1. Comparison of Low (<200 U/L) vs. Moderate (201–280 U/L) LDH Cohorts

4.2. Comparison of Low (<200 U/L) vs. High (≥281 U/L) LDH Cohorts

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, C.P.; Ferris, F.L., III; Klein, R.E.; Lee, P.P.; Agardh, C.D.; Davis, M.; Dills, D.; Kampik, A.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Verdaguer, J.T.; et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshfeghi, A.; Garmo, V.; Sheinson, D.; Ghanekar, A.; Abbass, I. Five-Year Patterns of Diabetic Retinopathy Progression in US Clinical Practice. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 3651–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perais, J.; Agarwal, R.; Evans, J.R.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Owens, D.; Hogg, R.E.; Lawrenson, J.G.; Takwoingi, Y.; Lois, N. Prognostic factors for the development and progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy in people with diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, CD013775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 12. Ophthalmology 1991, 98, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, D.A.; Silva, P.S.; Stitt, A.W. Current understanding of the molecular and cellular pathology of diabetic retinopathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhana, A.; Lappin, S.L. Biochemistry Lactate Dehydrogenase. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.; Xu, W.; Liu, L.; Yang, G. Association of lactate dehydrogenase and diabetic retinopathy in US adults with diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e13476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, X.; Zhu, M. Factors related to type 2 diabetic retinopathy and their clinical application value. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1484197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, C.; Pan, N.; Zhang, M.; An, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Tan, L. Serum lactate dehydrogenase activities as systems biomarkers for 48 types of human diseases. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Gui, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, R.; Shen, W.; Song, H. Role of glucose metabolism in ocular angiogenesis (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Noorden, C.J.; Yetkin-Arik, B.; Serrano Martinez, P.; Bakker, N.; van Breest Smallenburg, M.E.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Klaassen, I.; Majc, B.; Habic, A.; Bogataj, U.; et al. New Insights in ATP Synthesis as Therapeutic Target in Cancer and Angiogenic Ocular Diseases. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2024, 72, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiam, B.K.; Xu, L.; Berry, J.L. Aqueous Humor Markers in Retinoblastoma, a Review. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Moderate LDH (n = 14,615) | Low LDH (n = 13,514) | Standardized Difference | Moderate LDH (n = 11,708) | Low LDH (n = 11,708) | Standardized Difference |

| Age, mean ± SD | 63.5 ± 13.5 | 62.9 ± 13.7 | 0.0473 | 63.1 ± 13.5 | 63.2 ± 13.6 | 0.0034 |

| Gender, No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 6878 (49.92%) | 6493 (52.94%) | 0.0603 | 6121 (52.28%) | 6106 (52.15%) | 0.0026 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 7350 (53.35%) | 7120 (58.05%) | 0.0947 | 6708 (57.29%) | 6712 (57.33%) | 0.0007 |

| Black or African American | 3688 (26.77%) | 2764 (22.53%) | 0.0983 | 2762 (23.59%) | 2734 (23.35%) | 0.0056 |

| Asian | 554 (4.02%) | 512 (4.17%) | 0.0077 | 477 (4.07%) | 485 (4.14%) | 0.0034 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 145 (1.05%) | 100 (0.82%) | 0.0247 | 99 (0.85%) | 97 (0.83%) | 0.0019 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 133 (0.97%) | 93 (0.76%) | 0.0224 | 91 (0.78%) | 93 (0.79%) | 0.0019 |

| Other Race | 631 (4.58%) | 568 (4.63%) | 0.0024 | 537 (4.59%) | 540 (4.61%) | 0.0012 |

| Unknown Race | 1277 (9.27%) | 1109 (9.04%) | 0.0079 | 1034 (8.83%) | 1047 (8.94%) | 0.0039 |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1791 (13.00%) | 1549 (12.63%) | 0.0111 | 1482 (12.66%) | 1497 (12.79%) | 0.0038 |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | ||||||

| Essential (primary) hypertension | 11,983 (86.97%) | 10,369 (84.53%) | 0.0698 | 10,041 (85.76%) | 10,051 (85.85%) | 0.0024 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11,076 (80.39%) | 9563 (77.96%) | 0.0598 | 9269 (79.17%) | 9264 (79.13%) | 0.0011 |

| T2DM with mild NPDR without macular edema | 4092 (29.70%) | 3722 (30.34%) | 0.0141 | 3535 (30.19%) | 3502 (29.91%) | 0.0061 |

| T2DM with mild NPDR with macular edema | 787 (5.71%) | 656 (5.35%) | 0.0159 | 631 (5.39%) | 639 (5.46%) | 0.0030 |

| T2DM with moderate NPDR without macular edema | 1423 (10.33%) | 1141 (9.30%) | 0.0345 | 1092 (9.33%) | 1108 (9.46%) | 0.0047 |

| T2DM with moderate NPDR with macular edema | 764 (5.55%) | 607 (4.95%) | 0.0268 | 585 (5.00%) | 592 (5.06%) | 0.0027 |

| T2DM with severe NPDR without macular edema | 668 (4.85%) | 503 (4.10%) | 0.0362 | 474 (4.05%) | 489 (4.18%) | 0.0065 |

| T2DM with severe NPDR with macular edema | 464 (3.37%) | 353 (2.88%) | 0.0282 | 348 (2.97%) | 346 (2.96%) | 0.0010 |

| Primary open-angle glaucoma | 717 (5.20%) | 543 (4.43%) | 0.0363 | 531 (4.54%) | 533 (4.55%) | 0.0008 |

| Proteinuria | 3442 (24.98%) | 2599 (21.19%) | 0.0901 | 2613 (22.32%) | 2589 (22.11%) | 0.0049 |

| Alcohol dependence | 385 (2.79%) | 342 (2.79%) | 0.0004 | 320 (2.73%) | 327 (2.79%) | 0.0036 |

| Tobacco use | 783 (5.68%) | 679 (5.54%) | 0.0064 | 630 (5.38%) | 653 (5.58%) | 0.0086 |

| Central retinal artery occlusion | 57 (0.41%) | 45 (0.37%) | 0.0075 | 42 (0.36%) | 43 (0.37%) | 0.0014 |

| Retinal artery branch occlusion | 54 (0.39%) | 49 (0.40%) | 0.0012 | 49 (0.42%) | 47 (0.40%) | 0.0027 |

| Partial retinal artery occlusion | 43 (0.31%) | 41 (0.33%) | 0.0039 | 38 (0.33%) | 37 (0.32%) | 0.0015 |

| Central retinal vein occlusion | 199 (1.44%) | 160 (1.30%) | 0.0120 | 159 (1.36%) | 157 (1.34%) | 0.0015 |

| Tributary (branch) retinal vein occlusion | 193 (1.40%) | 150 (1.22%) | 0.0156 | 150 (1.28%) | 145 (1.24%) | 0.0038 |

| Low income | 68 (0.49%) | 41 (0.33%) | 0.0248 | 37 (0.32%) | 41 (0.35%) | 0.0059 |

| Intravitreal injection | 1360 (9.87%) | 1005 (8.19%) | 0.0585 | 998 (8.52%) | 993 (8.48%) | 0.0015 |

| Lab Values, mean ± SD | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 10.5 ± 2.37 | 10.9 ± 2.42 | 0.1826 | 10.5 ± 2.39 | 10.9 ± 2.41 | 0.1474 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 7.68 ± 1.97 | 7.64 ± 1.96 | 0.0246 | 7.69 ± 1.96 | 7.63 ± 1.96 | 0.0283 |

| Triglyceride | 148 ± 147 | 154 ± 136 | 0.0408 | 150 ± 153 | 154 ± 135 | 0.0301 |

| Cholesterol | 154 ± 53.7 | 152 ± 50.3 | 0.0511 | 154 ± 52.6 | 152 ± 50.3 | 0.0370 |

| Body Mass Index | 31.2 ± 7.88 | 30.8 ± 7.56 | 0.0461 | 31.3 ± 7.89 | 30.8 ± 7.54 | 0.0597 |

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | High LDH (n = 21,915) | Low LDH (n = 13,514) | Standardized Difference | High LDH (n = 12,154) | Low LDH (n = 12,154) | Standardized Difference |

| Age, mean ± SD | 62.6 ± 13.2 | 62.9 ± 13.7 | 0.0187 | 62.9 ± 13.3 | 62.9 ± 13.7 | 0.0009 |

| Gender, No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 10,257 (50.05%) | 6493 (52.94%) | 0.0577 | 6468 (53.22%) | 6417 (52.80%) | 0.0084 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 10,202 (49.78%) | 7120 (58.05%) | 0.1664 | 7087 (58.31%) | 7039 (57.92%) | 0.0080 |

| Black or African American | 6169 (30.10%) | 2764 (22.53%) | 0.1725 | 2721 (22.39%) | 2757 (22.68%) | 0.0071 |

| Asian | 909 (4.44%) | 512 (4.17%) | 0.0129 | 531 (4.37%) | 505 (4.16%) | 0.0106 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 143 (0.70%) | 93 (0.76%) | 0.0071 | 96 (0.79%) | 93 (0.77%) | 0.0028 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 199 (0.97%) | 100 (0.82%) | 0.0166 | 91 (0.75%) | 99 (0.82%) | 0.0075 |

| Other Race | 862 (4.21%) | 568 (4.63%) | 0.0207 | 556 (4.58%) | 560 (4.61%) | 0.0016 |

| Unknown Race | 2009 (9.80%) | 1109 (9.04%) | 0.0261 | 1072 (8.82%) | 1101 (9.06%) | 0.0084 |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 2355 (11.49%) | 1549 (12.63%) | 0.0349 | 1504 (12.38%) | 1527 (12.56%) | 0.0057 |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | ||||||

| Essential (primary) hypertension | 18,027 (87.97%) | 10,369 (84.53%) | 0.0998 | 10,311 (84.84%) | 10,300 (84.75%) | 0.0025 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 16,602 (81.01%) | 9563 (77.96%) | 0.0756 | 9536 (78.46%) | 9508 (78.23%) | 0.0056 |

| T2DM with mild NPDR without macular edema | 5704 (27.83%) | 3722 (30.34%) | 0.0553 | 3703 (30.47%) | 3673 (30.22%) | 0.0054 |

| T2DM with mild NPDR with macular edema | 980 (4.78%) | 656 (5.35%) | 0.0258 | 663 (5.46%) | 649 (5.34%) | 0.0051 |

| T2DM with moderate NPDR without macular edema | 1958 (9.55%) | 1141 (9.30%) | 0.0086 | 1166 (9.59%) | 1125 (9.26%) | 0.0115 |

| T2DM with moderate NPDR with macular edema | 928 (4.53%) | 607 (4.95%) | 0.0198 | 608 (5.00%) | 600 (4.94%) | 0.0030 |

| T2DM with severe NPDR without macular edema | 951 (4.64%) | 503 (4.10%) | 0.0264 | 501 (4.12%) | 501 (4.12%) | 0.0000 |

| T2DM with severe NPDR with macular edema | 589 (2.87%) | 353 (2.88%) | 0.0002 | 366 (3.01%) | 351 (2.89%) | 0.0073 |

| Primary open-angle glaucoma | 1044 (5.09%) | 543 (4.43%) | 0.0314 | 516 (4.25%) | 542 (4.46%) | 0.0105 |

| Proteinuria | 5033 (24.56%) | 2599 (21.19%) | 0.0803 | 2598 (21.38%) | 2591 (21.32%) | 0.0014 |

| Alcohol dependence | 720 (3.51%) | 342 (2.79%) | 0.0415 | 323 (2.66%) | 340 (2.80%) | 0.0086 |

| Tobacco use | 1155 (5.64%) | 679 (5.54%) | 0.0044 | 678 (5.58%) | 678 (5.58%) | 0.0000 |

| Central retinal artery occlusion | 86 (0.42%) | 45 (0.37%) | 0.0084 | 43 (0.35%) | 45 (0.37%) | 0.0027 |

| Retinal artery branch occlusion | 74 (0.36%) | 49 (0.40%) | 0.0062 | 46 (0.38%) | 49 (0.40%) | 0.0040 |

| Partial retinal artery occlusion | 65 (0.32%) | 41 (0.33%) | 0.0030 | 39 (0.32%) | 41 (0.34%) | 0.0029 |

| Central retinal vein occlusion | 243 (1.19%) | 160 (1.30%) | 0.0107 | 155 (1.28%) | 157 (1.29%) | 0.0015 |

| Tributary (branch) retinal vein occlusion | 252 (1.23%) | 150 (1.22%) | 0.0006 | 149 (1.23%) | 146 (1.20%) | 0.0023 |

| Low income | 86 (0.42%) | 41 (0.33%) | 0.0139 | 38 (0.31%) | 41 (0.34%) | 0.0043 |

| Intravitreal injection | 1779 (8.68%) | 1005 (8.19%) | 0.0175 | 991 (8.15%) | 1000 (8.23%) | 0.0027 |

| Lab Values, mean ± SD | ||||||

| Hemoglobin | 10.1 ± 2.32 | 10.9 ± 2.42 | 0.3197 | 10.2 ± 2.34 | 10.9 ± 2.42 | 0.2917 |

| Hemoglobin A1c | 7.7 ± 2.01 | 7.64 ± 1.96 | 0.0340 | 7.69 ± 1.99 | 7.64 ± 1.96 | 0.0256 |

| Triglyceride | 155 ± 129 | 154 ± 136 | 0.0081 | 157 ± 131 | 154 ± 136 | 0.0202 |

| Cholesterol | 154 ± 54.2 | 152 ± 50.3 | 0.0466 | 152 ± 53.7 | 152 ± 50.4 | 0.0048 |

| Body Mass Index | 31 ± 7.79 | 30.8 ± 7.56 | 0.0169 | 30.9 ± 7.69 | 30.8 ± 7.55 | 0.0091 |

| Code System | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ICD-10-CM | I10 | Essential (primary) hypertension |

| ICD-10-CM | E78 | Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism and other lipidemias |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.329 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with mild NPDR without macular edema |

| ICD-10-CM | R80 | Proteinuria |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.339 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with moderate NPDR without macular edema |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.321 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with mild NPDR with macular edema |

| ICD-10-CM | Z72.0 | Tobacco use |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.331 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with moderate NPDR with macular edema |

| ICD-10-CM | H40.11 | Primary open-angle glaucoma |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.349 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with severe NPDR without macular edema |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.341 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with severe NPDR with macular edema |

| ICD-10-CM | F10.2 | Alcohol dependence |

| ICD-10-CM | H34.81 | Central retinal vein occlusion |

| ICD-10-CM | H34.83 | Tributary (branch) retinal vein occlusion |

| ICD-10-CM | H34.23 | Retinal artery branch occlusion |

| ICD-10-CM | H34.1 | Central retinal artery occlusion |

| ICD-10-CM | H34.21 | Partial retinal artery occlusion |

| ICD-10-CM | Z59.6 | Low income |

| CPT | 67028 | Intravitreal injection of a pharmacologic agent (separate procedure) |

| TNX Curated | 9014 | Hemoglobin [Mass/volume] in Blood |

| TNX Curated | 9037 | Hemoglobin A1c/Hemoglobin. Total in Blood |

| TNX Curated | 9004 | Triglyceride [Mass/volume] in Serum, Plasma, or Blood |

| TNX Curated | 9083 | Body Mass Index (BMI) |

| TNX Curated | 9000 | Cholesterol [Mass/volume] in Serum or Plasma |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.33 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with moderate NPDR |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.31 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with unspecified diabetic retinopathy |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.32 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with mild NPDR |

| ICD-10-CM | E11.34 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus with severe NPDR |

| TNX Curated | 9052 | Lactate dehydrogenase [Enzymatic activity/volume] in Serum or Plasma |

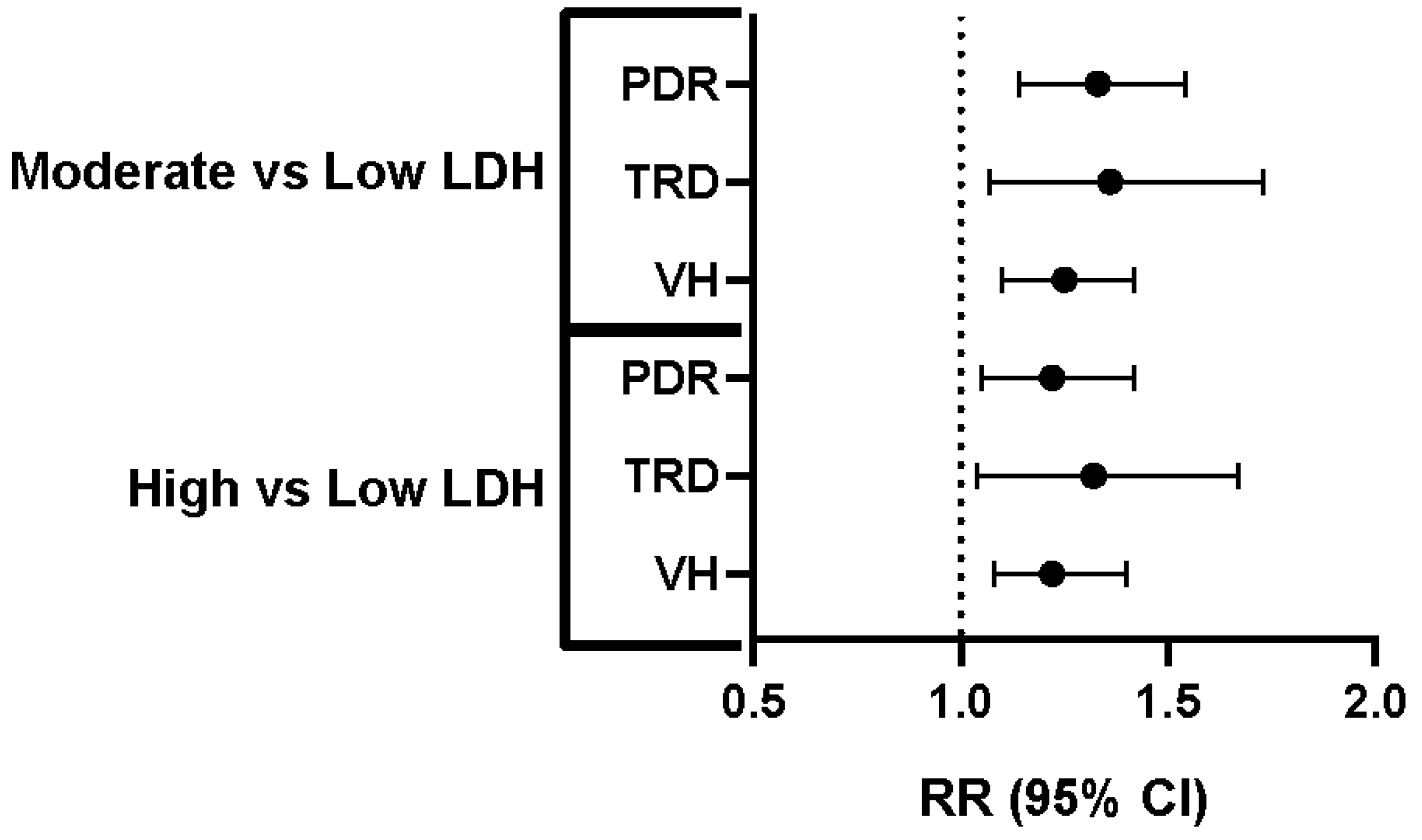

| Comparison | Outcome | Risk (%)–Low LDH | Risk (%)–Comparison Group | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low vs. Moderate LDH | PDR | 2.96% | 3.93% | 1.33 (1.14–1.54) |

| Low vs. Moderate LDH | TRD | 0.99% | 1.35% | 1.36 (1.07–1.73) |

| Low vs. Moderate LDH | VH | 3.51% | 4.38% | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) |

| Low vs. High LDH | PDR | 3.00% | 3.66% | 1.22 (1.05–1.42) |

| Low vs. High LDH | TRD | 0.96% | 1.27% | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) |

| Low vs. High LDH | VH | 0.96% | 1.27% | 1.22 (1.08–1.40) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shosha, E.; Chauhan, M.Z.; Muayad, J.; Sallam, A.B.; Fouda, A.Y. Systemic Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels as a Predictor of Progression from Non-Proliferative to Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248696

Shosha E, Chauhan MZ, Muayad J, Sallam AB, Fouda AY. Systemic Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels as a Predictor of Progression from Non-Proliferative to Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248696

Chicago/Turabian StyleShosha, Esraa, Muhammad Z. Chauhan, Jawad Muayad, Ahmed B. Sallam, and Abdelrahman Y. Fouda. 2025. "Systemic Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels as a Predictor of Progression from Non-Proliferative to Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248696

APA StyleShosha, E., Chauhan, M. Z., Muayad, J., Sallam, A. B., & Fouda, A. Y. (2025). Systemic Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels as a Predictor of Progression from Non-Proliferative to Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8696. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248696