Combined Laparoscopic–Robotic Partial Nephrectomy: A Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency and Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

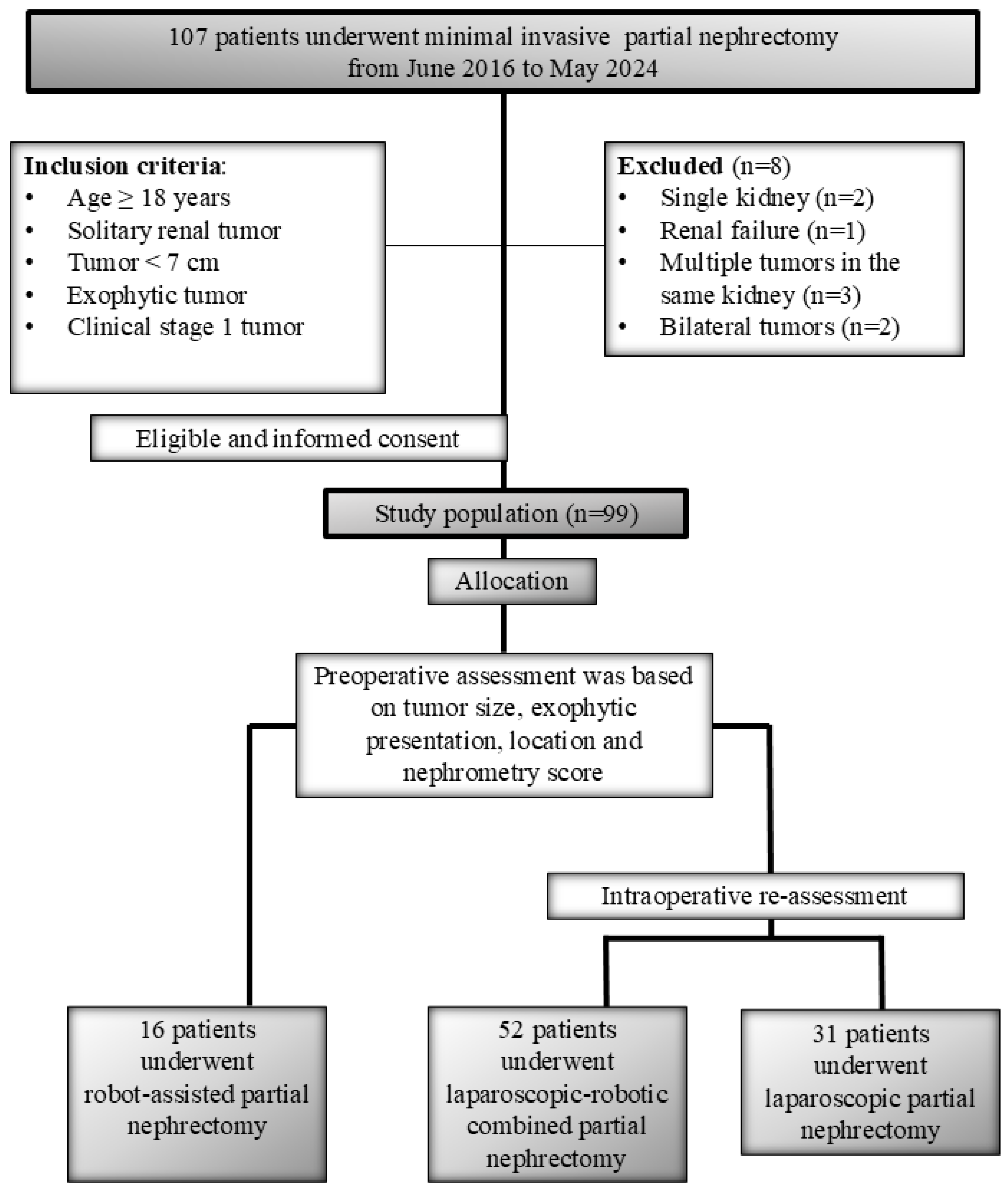

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

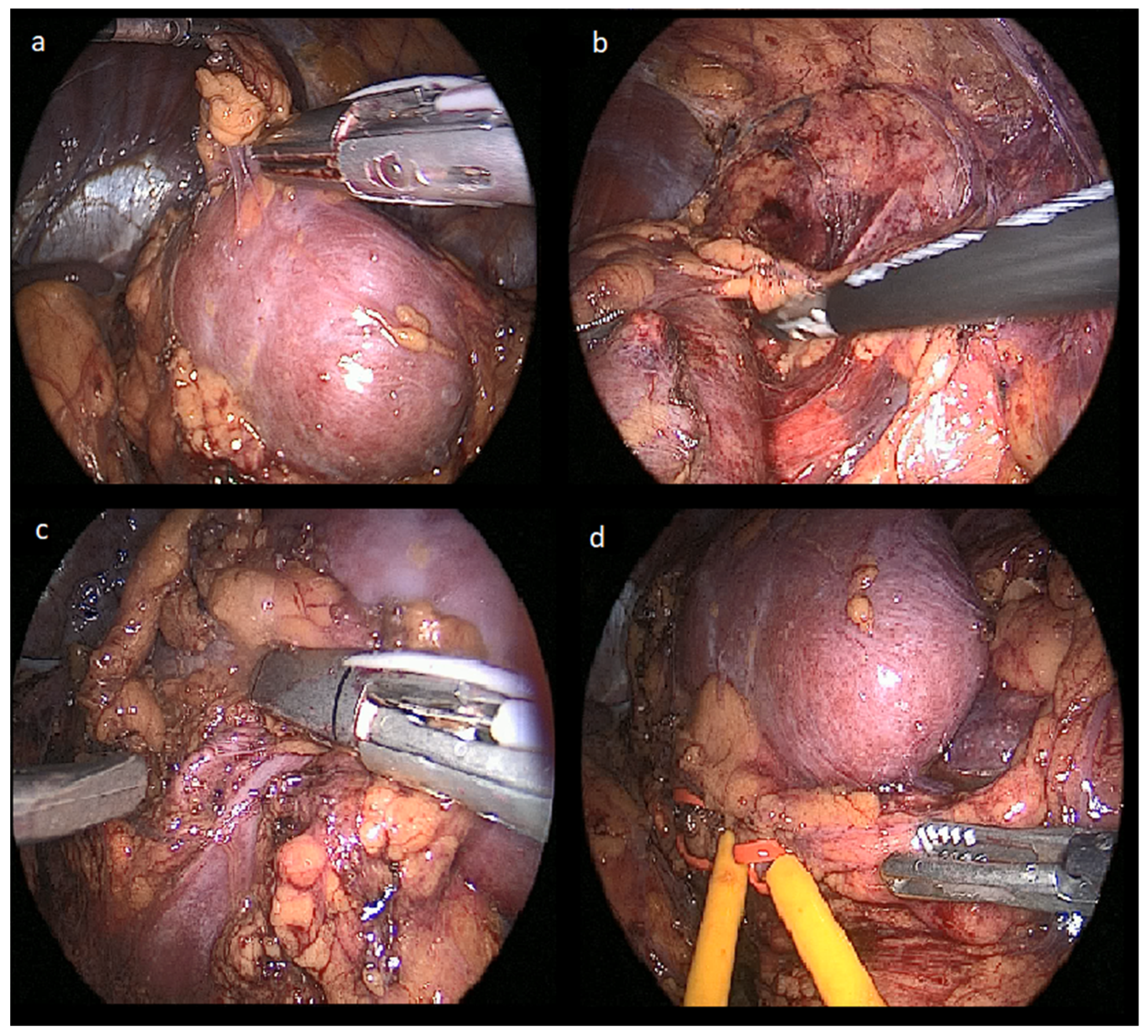

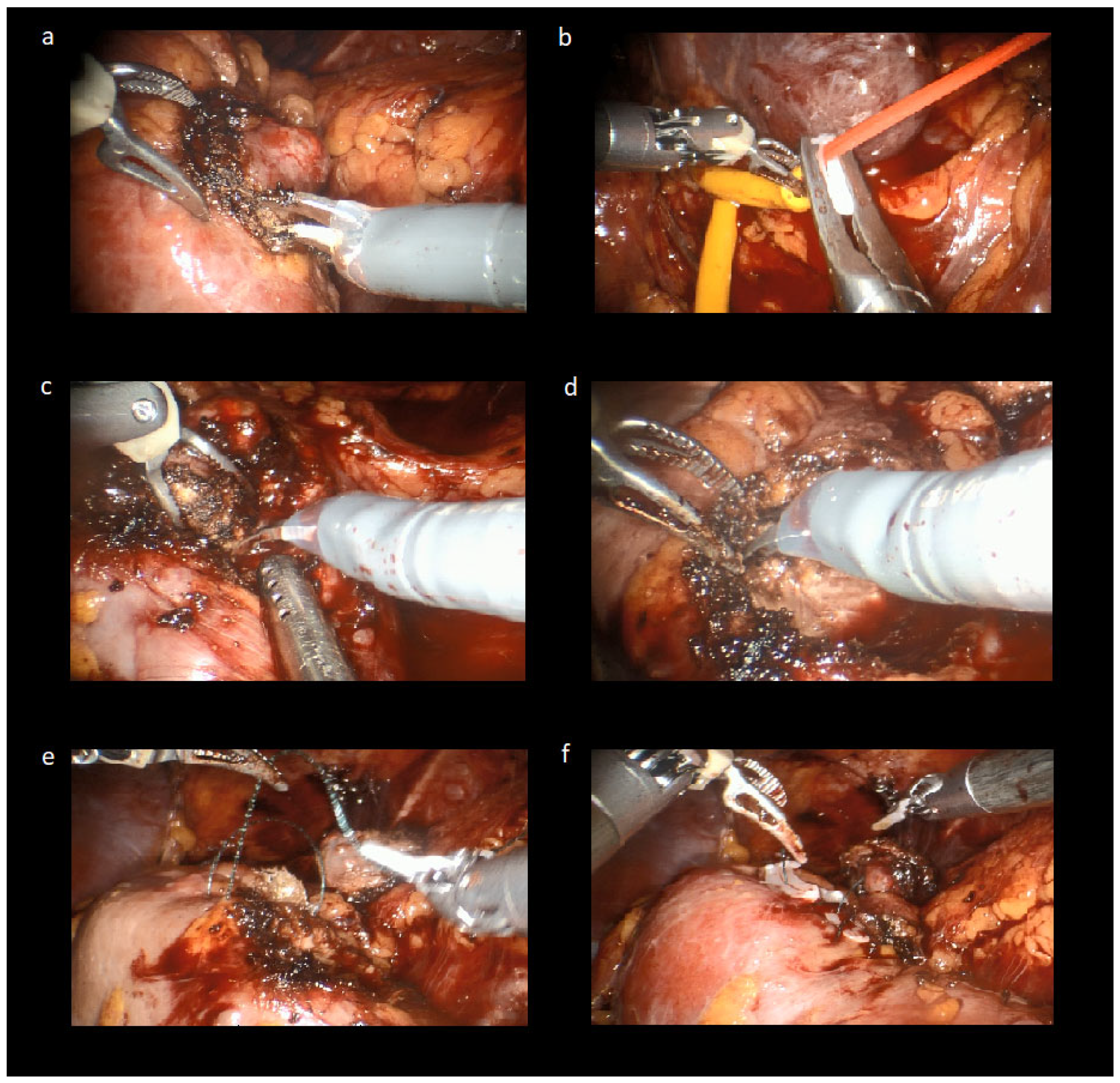

2.2. Laparoscopic-Robotic Combined Partial Nephrectomy Surgical Technique

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capitanio, U.; Bensalah, K.; Bex, A.; Boorjian, S.A.; Bray, F.; Coleman, J.; Gore, J.L.; Sun, M.; Wood, C.; Russo, P. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhawere, K.E.; Pandav, K.; Grauer, R.; Wilson, M.P.; Saini, I.; Korn, T.G.; Meilika, K.N.; Badani, K.K. Trends in the surgical management of kidney cancer by tumor stage, treatment modality, facility type, and location. J. Robot. Surg. 2023, 17, 2451–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabell, J.R.; Wu, J.; Suk-Ouichai, C.; Campbell, S.C. Renal Ischemia and Functional Outcomes Following Partial Nephrectomy. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 44, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calpin, G.G.; Ryan, F.R.; McHugh, F.T.; McGuire, B.B. Comparing the outcomes of open, laparoscopic and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: A network meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2023, 132, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexner, S.D.; Bergamaschi, R.; Lacy, A.; Udo, J.; Brölmann, H.; Kennedy, R.H.; John, H. The current status of robotic pelvic surgery: Results of a multinational interdisciplinary consensus conference. Surg. Endosc. 2009, 23, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Guerrero, E.; Claro, A.V.O.; Ledo Cepero, M.J.; Soto Delgado, M.; Álvarez-Ossorio Fernández, J.L. Robotic versus laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in the new era: Systematic review. Cancers 2023, 15, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, J.M.; Shapiro, O.; Moinzadeh, A. Comparison of laparoscopic versus robotic assisted partial nephrectomy: One surgeon’s initial experience. Can. J. Urol. 2010, 17, 5207–5212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thakker, P.U.; O’Rourke, T.K., Jr.; Hemal, A.K. Technologic advances in robot-assisted nephron sparing surgery: A narrative review. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2023, 12, 1184–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutikov, A.; Uzzo, R.G. The RENAL nephrometry score: A comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of Surgical Complications: A New Proposal With Evaluation in a Cohort of 6336 Patients and Results of a Survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunc, L.; Canda, A.E.; Polat, F.; Onaran, M.; Atkin, S.; Biri, H.; Bozkirli, I. Direct upper kidney pole access and early ligation of renal pedicle significantly facilitates transperitoneal laparoscopic nephrectomy procedures: Tunc technique. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2011, 21, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, S.M.; Mellon, M.J.; Erntsberger, L.; Sundaram, C.P. A comparison of robotic, laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomy. JSLS J. Soc. Laparoendosc. Surg. 2012, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinata, N.; Shiroki, R.; Tanabe, K.; Eto, M.; Takenaka, A.; Kawakita, M.; Hara, I.; Hongo, F.; Ibuki, N.; Nasu, Y.; et al. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy versus standard laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for renal hilar tumor: A prospective multi-institutional study. Int. J. Urol. 2021, 28, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, K.B.; Schober, J.P.; Kutikov, A. Ischemia Time Has Little Influence on Renal Function Following Partial Nephrectomy: Is It Time for Urology to Stop the Tick-Tock Dance? Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, Q.; Peyronnet, B.; Sebe, P.; Cote, J.-F.; Kammerer-Jacquet, S.-F.; Khene, Z.-E.; Pradere, B.; Mathieu, R.; Verhoest, G.; Guillonneau, B.; et al. Comparison of short-term functional, oncological, and perioperative outcomes between laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomy beyond the learning curve. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2018, 28, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, A.D.; Miano, R.; Annino, F.; Micali, S.; Spera, E.; Iorio, B.; Vespasiani, G.; Gaston, R. Robotic radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review. BMC Urol. 2014, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboumarzouk, O.M.; Stein, R.J.; Eyraud, R.; Haber, G.-P.; Chlosta, P.L.; Somani, B.K.; Kaouk, J.H. Robotic versus laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routh, J.C.; Bacon, D.R.; Leibovich, B.C.; Zincke, H.; Blute, M.L.; Frank, I. How long is too long? The effect of the duration of anaesthesia on the incidence of non-urological complications after surgery. BJU Int. 2008, 102, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artsitas, S.; Artsitas, D.; Koronaki, I.; Toutouzas, K.G.; Zografos, G.C. Comparing robotic and open partial nephrectomy under the prism of surgical precision: A meta-analysis of the average blood loss rate as a novel variable. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sri, D.; Thakkar, R.; Patel, H.; Lazarus, J.; Berger, F.; McArthur, R.; Lavigueur-Blouin, H.; Afshar, M.; Fraser-Taylor, C.; Le Roux, P.; et al. Robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) and standardization of outcome reporting: A prospective, observational study on reaching the “Trifecta and Pentafecta”. J. Robot. Surg. 2021, 15, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malthouse, T.; Kasivisvanathan, V.; Raison, N.; Lam, W.; Challacombe, B. The future of partial nephrectomy. Int. J. Surg. 2016, 36, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| LPN n = 31 | RAPN n = 16 | CPN n = 52 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 59.6 ± 10.9 | 59.6 ± 8.4 | 59.4 ± 11.9 | 0.935 |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 26 (83.9) | 12 (75.0) | 43 (82.7) | 0.735 |

| BMI score (mean ± SD) | 28.1 ± 5.0 | 28.0 ± 4.7 | 27.7 ± 4.2 | 0.806 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 12 (38.7) | 9 (56.3) | 23 (44.2) | 0.518 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 13 (41.9) | 8 (50.0) | 15 (25.8) | 0.226 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 4 (25.0) | 13 (25.0) | 0.562 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.8) | 0.596 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) (g/dL) (mean ± SD) | 14.4 ± 1.2 | 13.7 ± 1.0 | 14.4 ± 1.2 | 0.141 |

| Preoperative serum creatinine (Cre) (mg/dL) (median, IQR) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.884 |

| Preoperative eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) (median, IQR) | 96.6 (83.2–108.8) | 85.6 (70.7–100.4) | 94.7 (71.3–100.0) | 0.115 |

| Side of tumor, n (%) Right Left | 16 (51.6) 15 (48.4) | 7 (43.7) 9 (56.3) | 24 (46.1) 28 (53.9) | 0.884 |

| Polar localization of tumor, n (%) Upper pole Middle Lower pole | 12 (38.7) 10 (32.3) 9 (29.0) | 6 (37.5) 6 (37.5) 4 (25.0) | 19 (36.5) 18 (34.6) 15 (28.8) | 0.996 |

| Axial localization of tumor, n (%) Medial Lateral Anterior Posterior | 7 (22.6) 12 (38.7) 5 (16.1) 7 (22.6) | 5 (31.3) 5 (31.3) 2 (12.5) 4 (25.0) | 20 (38.5) 16 (30.8) 6 (11.5) 10 (19.2) | 0.873 |

| LPN n = 31 | RAPN n = 16 | CPN n = 52 | p Value for CPN vs. LPN | p Value for CPN vs. RAPN | p Value for LPN vs. RAPN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (mm) (median, IQR) | 27.5 (20.0–36.7) | 34.0 (31.0–41.0) | 36.5 (32.2–44.7) | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.405 |

| Preoperative RENAL nephrometry score (median, IQR) | 6.0 (5.0–7.0) | 6.0 (5.2–7.7) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | <0.001 | 0.340 | 0.001 |

| Intraoperative RENAL nephrometry score (median, IQR) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 6.0 (4.0–9.0) | 7.5 (5–9) | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| CPN n = 31 | LPN n = 31 | p Value for CPN vs. LPN | CPN n = 16 | RAPN n = 16 | p Value for CPN vs. RaPN | LPN n = 16 | RAPN n = 16 | p Value for LPN vs. RaPN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 3 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ||||

| Tumor size (mm) (median, IQR) | 35.0 (28.0–42.0) | 34.0 (31.0–39.5) | 0.544 | 42.0 (31.0–46.5) | 36.5 (32.5–44.5) | 0.515 | 36.5 (29.0–49.0) | 36.5 (32.5–44.5) | 0.956 |

| Preoperative RENAL nephrometry score (median, IQR) | 7.0 (5.0–7.0) | 5.0 (4.0–5.0) | <0.001 | 7.0 (7.0–8.0) | 7.5 (6.5–8.0) | 0.468 | 4.5 (4.0–6.0) | 7.5 (6.5–8.0) | <0.001 |

| LPN n = 31 | RAPN n = 16 | CPN n = 52 | p Value for CPN vs. LPN | p Value for CPN vs. RAPN | p Value for LPN vs. RAPN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney dissection time (min) (median, IQR) | 45.7 (36.2–62.3) | 97.5 (87.7–106.5) | 48.0 (43.0–53.0) | 0.480 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Tumor resection time (min) (median, IQR) | 8.0 (4.0–12.0) | 5 (3.0–8.0) | 6.0 (3.0–11.5) | 0.012 | 0.023 | <0.001 |

| Parenchymal reconstruction time (min) (median, IQR) | 16.0 (11.0–23.0) | 13.5 (10.0–16.0) | 13.0 (6.0–20.0) | <0.001 | 0.500 | 0.001 |

| Warm ischemia time (WIT) (min) (median, IQR) | 23.0 (18.0–28.0) | 18.5 (14.0–23.0) | 20.0 (10.0–26.0) | <0.001 | 0.158 | <0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss (EBL) (mL) (median, IQR) | 180.0 (100.0–250.0) | 110.0 (50.0–300.0) | 120.0 (50.0–350.0) | 0.003 | 0.416 | 0.003 |

| Total operative time (OT) (min) (mean ± SD) | 136.87 ± 9.85 | 155.5 ± 18.03 | 126.75 ± 25.28 | 0.014 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CPN n = 31 | LPN n = 31 | p Value for CPN vs. LPN | CPN n = 16 | RAPN n = 16 | p Value for CPN vs. RaPN | LPN n = 16 | RAPN n = 16 | p Value for LPN vs. RaPN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 1 | Group 3 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ||||

| Kidney dissection time (min) (mean ± SD) | 49.4 ± 18.6 | 48.8 ± 7.1 | 0.875 | 48.5 ± 16.5 | 97.4 ± 13.1 | <0.001 | 49.8 ± 7.2 | 97.4 ± 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Tumor resection time (min) (mean ± SD) | 6.3 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 1.9 | 0.032 | 6.2 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 0.059 | 7.1 ± 2.1 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 0.003 |

| Parenchymal reconstruction time (min) (median, IQR) | 13.0 (10.0–14.0) | 16.0 (14.5–16.7) | <0.001 | 11.7 (10.0–14.75) | 13.5 (11.5–14.5) | 0.341 | 16.0 (15.0–16.25) | 13.5 (11.5–14.5) | <0.001 |

| Warm ischemia time (WIT) (min) (median, IQR) | 19.0 (17.0–21.7) | 23.0 (21.2–25.0) | <0.001 | 21.2 (16.5–22.2) | 18.5 (15.5–21.0) | 0.287 | 22.5 (21.0–25.5) | 18.5 (15.5–21.0) | <0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss (EBL) (mL) (mean ± SD) | 141.7 ± 70.0 | 176.2 ± 47.2 | 0.027 | 148.4 ± 71.2 | 129.0 ± 62.1 | 0.419 | 164.3 ± 48.0 | 129.0 ± 62.1 | 0.082 |

| Total operative time (OT) (min) (median, IQR) | 126 (109.0–138.5) | 134.0 (130.0–138.0) | 0.029 | 132.5 (117.0–140.5) | 152.5 (145.5–166.5) | 0.001 | 134.5 (130.0–136.0) | 152.5 (145.5–166.5) | <0.001 |

| LPN n = 31 | RAPN n = 16 | CPN n = 52 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin decrease (g/dL) (median, IQR) | 1.6 (1.0–1.8) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 1.5 (1.1–2.3) | 0.447 |

| Serum creatinine increase (mg/dL) (median, IQR) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.2 (0.2–0.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.013 |

| eGFR decrease (mL/min/1.73 m2) (mean ± SD) | 24.1 ± 9.8 | 16.2 ± 6.4 | 18.8 ± 13.6 | 0.156 |

| Hospitalization time (days) (median, IQR) | 3.0 (3.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–3.7) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 0.228 |

| Complications, n (%) Clavien-Dindo grade 1 Clavien-Dindo grade 2 Clavien-Dindo grade 3 Clavien-Dindo grade 4 | 2 (6.4) 2 (6.4) 0 (0) 0 (0) | 1 (6.2) 1 (6.2) 0 (0) 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) 3 (5.7) 0 (0) 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Histology, n (%) Clear cell RCC Papillary RCC Oncocytoma Chromophobe RCC Angiomyolipoma Undifferentiated RCC Benign renal cyst Oncocytic carcinoma Sarcoma | 14 (45.2) 7 (22.6) 3 (9.7) 2 (6.5) 3 (9.7) 2 (6.5) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) | 9 (56.3) 3 (18.8) 1 (6.3) 1 (6.3) 2 (12.5) 0 0 0 0 | 29 (55.8) 6 (11.5) 5 (9.6) 5 (9.6) 3 (5.8) 1 (1.9) 1 (1.9) 1 (1.9) 1 (1.9) | 0.951 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barlas, I.S.; Yilmaz, M.; Aybal, H.C.; Duvarci, M.; Guven, S.; Tunc, L. Combined Laparoscopic–Robotic Partial Nephrectomy: A Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency and Safety. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248693

Barlas IS, Yilmaz M, Aybal HC, Duvarci M, Guven S, Tunc L. Combined Laparoscopic–Robotic Partial Nephrectomy: A Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency and Safety. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248693

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarlas, Irfan Safak, Mehmet Yilmaz, Halil Cagri Aybal, Mehmet Duvarci, Selcuk Guven, and Lutfi Tunc. 2025. "Combined Laparoscopic–Robotic Partial Nephrectomy: A Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency and Safety" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248693

APA StyleBarlas, I. S., Yilmaz, M., Aybal, H. C., Duvarci, M., Guven, S., & Tunc, L. (2025). Combined Laparoscopic–Robotic Partial Nephrectomy: A Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency and Safety. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8693. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248693