Assessing the Learning Curve in Conduction System Pacing Implantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Inadequate coronary sinus venous anatomy (absence of suitable lateral or postero-lateral branches, or only anterior, posterior, or apical veins available);

- Lack of QRS narrowing during biventricular pacing.

2.1. CSP with His Bundle Pacing

2.2. CSP with Left Bundle Branch Pacing

- Achievement of a stable and selective or non-selective LBBAP/His capture;

- R-R’ in V1 and blocked ectopic beats were present;

- Appropriate 12-lead ECG pattern consistent with CSP physiology;

- LVAT measurement confirming physiological activation, according to the EHRA document [5];

- Acceptable pacing thresholds and sensing parameters.

2.2.1. Clinical Data

2.2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

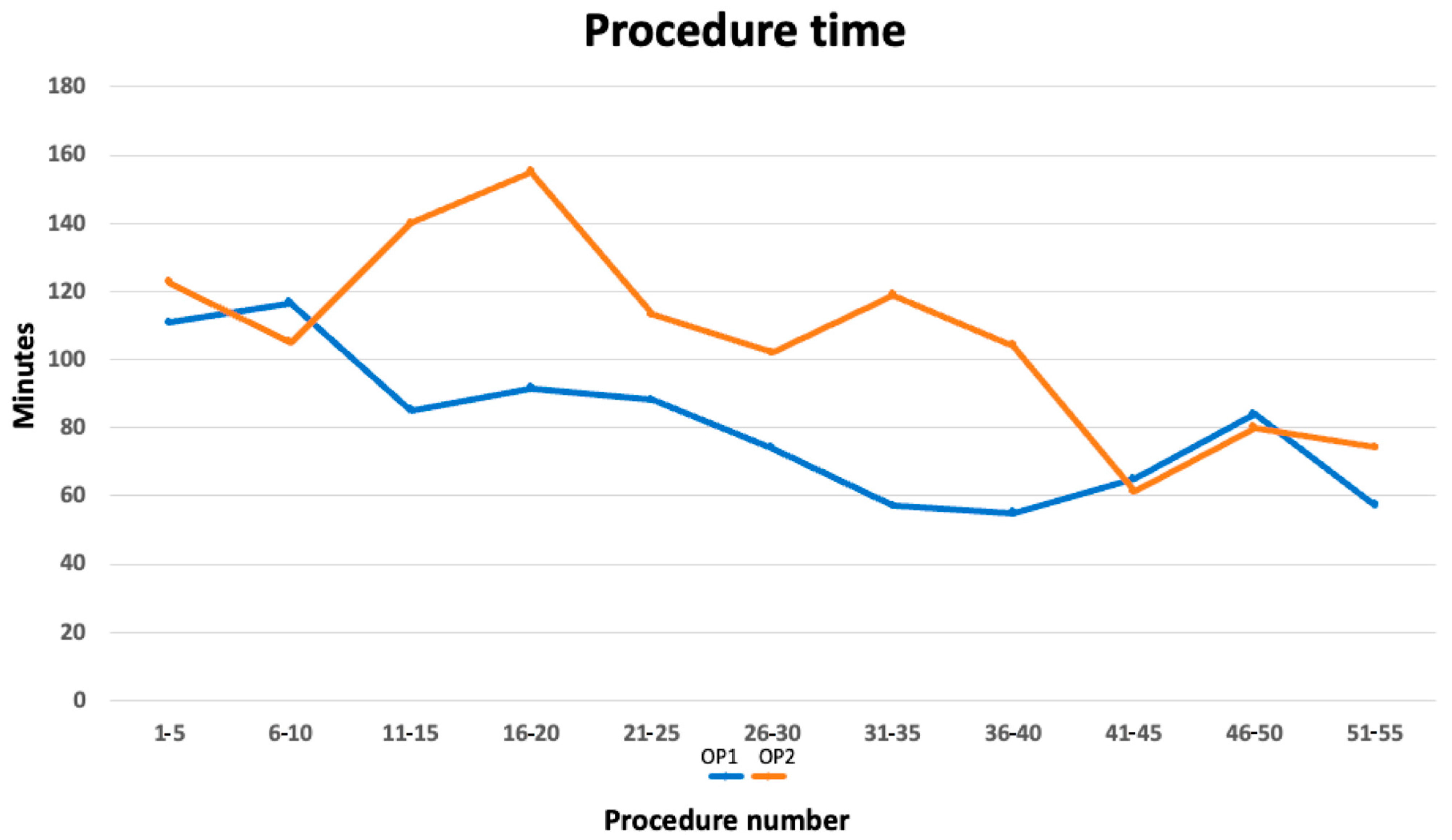

3.1. Procedure Duration

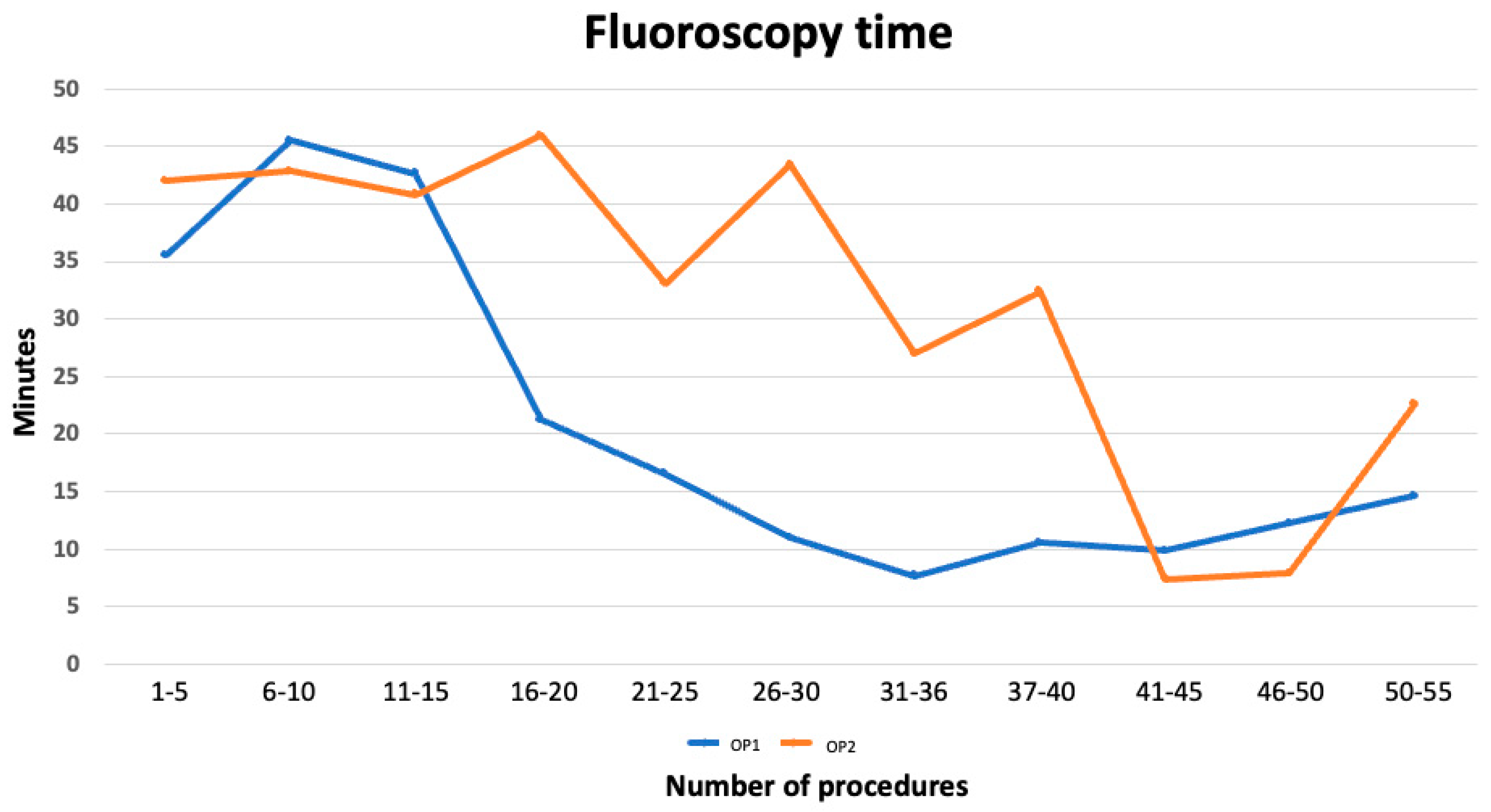

3.2. Fluoroscopy Time

3.3. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

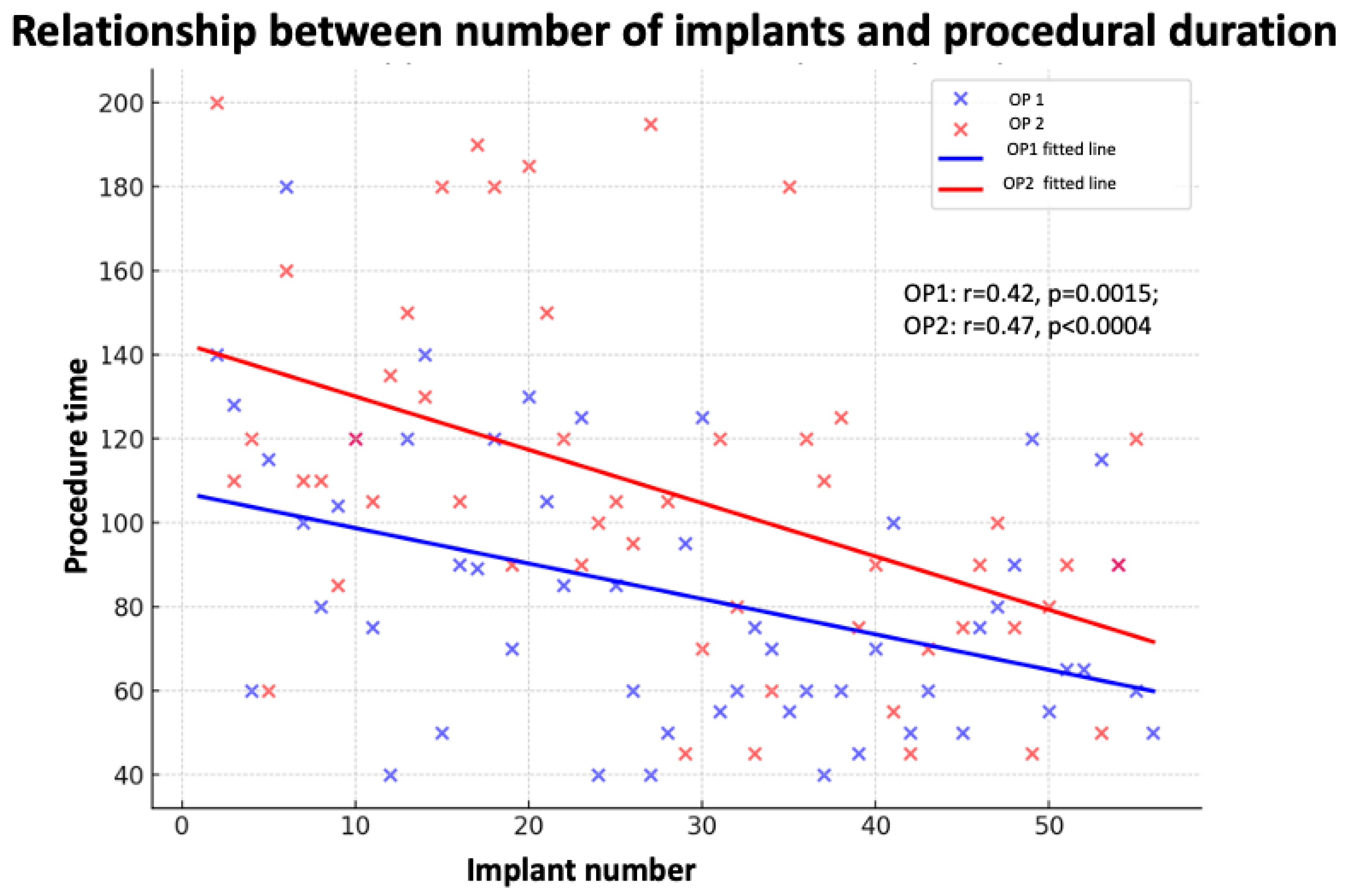

3.3.1. Implantation Time

3.3.2. Fluoroscopy Time

3.3.3. Complications

3.4. Figures, Tables, and Schemes

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glikson, M.; Nielsen, J.C.; Kronborg, M.B.; Michowitz, Y.; Auricchio, A.; Barbash, I.M.; Barrabés, J.A.; Boriani, G.; Braunschweig, F.; Brignole, M.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: Developed by the Task Force on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3427–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraman, P.; Dandamudi, G.; Zanon, F.; Sharma, P.S.; Tung, R.; Huang, W.; Koneru, J.; Tada, H.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; Lustgarten, D.L. Permanent His bundle pacing: Recommendations from a Multicenter His Bundle Pacing Collaborative Working Group for standardization of definitions, implant measurements, and follow-up. Heart. Rhythm. 2018, 15, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayaraman, P.; Ponnusamy, S.; Cano, O.; Sharma, P.S.; Naperkowski, A.; Subsposh, F.A.; Moskal, P.; Bednarek, A.; Forno, A.R.D.; Young, W.; et al. Left bundle branch area pacing for cardiac resynchronization therapy: Results from the International LBBAP Collaborative Study Group. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2021, 7, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.K.; Patton, K.K.; Lau, C.P.; Dal Forno, A.R.J.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Arora, V.; Birgersdotter-Green, U.M.; Cha, Y.M.; Chung, E.H.; Cronin, E.M.; et al. 2023 HRS/APHRS/LAHRS guideline on cardiac physiologic pacing for the avoidance and mitigation of heart failure. J. Arrhythmia 2023, 39, 681–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burri, H.; Jastrzebski, M.; Cano, Ó.; Čurila, K.; de Pooter, J.; Huang, W.; Israel, C.; Joza, J.; Romero, J.; Vernooy, K.; et al. EHRA clinical consensus statement on conduction system pacing implantation: Endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). EP Eur. 2023, 25, 1208–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Barilli, M.; Marallo, C.; Baiocchi, C. The interventricular conduction delays guide best cardiac resynchronization therapy: A tailored-patient approach to perform a CRT through Conduction System Pacing. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol. J. 2024, 24, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taddeucci, S.; Marallo, C.; Merello, G.; Santoro, A. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with conduction system pacing in a long-term heart transplant recipient: A case report. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol. J. 2024, 24, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santoro, A.; Landra, F.; Marallo, C.; Taddeucci, S.; Sisti, N.; Pica, A.; Stefanini, A.; Tavera, M.C.; Pagliaro, A.; Baiocchi, C.; et al. Biventricular or Conduction System Pacing for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy: A Strategy for Cardiac Resynchronization Based on a Hybrid Approach. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marallo, C.; Landra, F.; Taddeucci, S.; Collantoni, M.; Martini, L.; Lunghetti, S.; Pagliaro, A.; Menci, D.; Baiocchi, C.; Fineschi, M.; et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy guided by interventricular conduction delay: How to choose between biventricular pacing or conduction system pacing. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2024, 35, 2345–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of echocardiography and the European Association Of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, A.; Taddeucci, S. Helix breakage during left bundle pacing area implantation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 1192–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.; Shi, R.; Kramer, D.B.; Riad, O.; Hunnybun, D.; Jarman, J.W.E.; Foran, J.; Cantor, E.; Markides, V.; Wong, T. Conduction system pacing learning curve: Left bundle pacing compared to His bundle pacing. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2023, 44, 101171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marion, W.; Schanz JDJr Patel, S.; Co, M.L.; Pavri, B.B. Single operator experience, learning curve, outcomes, and insights gained with conduction system pacing. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 47, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddeucci, S.; Mirizzi, G.; Santoro, A. Lumenless and Stylet-Driven Leads for Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing: Materials, Techniques, Benefits, and Trade-Offs of the Two Approaches. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Su, L.; Wu, S.; Xia, X.; Vijayaraman, P. A beginner’s guide to permanent left bundle branch pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2019, 16, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, T.D.; Himes, A.; Marshall, M.; Crossley, G.H. Rationale for and use of the lumenless 3830 pacing lead. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2023, 34, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pooter, J.; Wauters, A.; Van Heuverswyn, F.; Le Polain de Waroux, J.B. A Guide to Left Bundle Branch Area Pacing Using Stylet-Driven Pacing Leads. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 844152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Dong, J. Stylet-driven leads compared with lumenless leads for left bundle branch area pacing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Female (n. %) | AGE (m/SD) | BSA (m/SD) | RWT m/SD | LVEDD (m/SD) | EF % (m/SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP 1 | 18/32.7 | 75.5 ± 8.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.42 ± 0.13 | 59.3 ± 9.4 | 41.7 ± 15.3 |

| OP 2 | 15/27.3 | 72.9 ± 25.9 | 1 ± 0.2 | 0.41 ± 0.2 | 57.4 ± 26.3 | 40.2 ± 22.3 |

| Bailout (n./%) | AVB (n./%) | A/P (n./%) | pQRS ms (m/SD) | LVAT ms (m/SD) | HV ms (m/SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OP 1 | 41/74.5 | 7/12.7 | 7/12.7 | 108.2 ± 13.2 | 69.9 ± 10.1 | 43.7 ± 15.4 |

| OP 2 | 43/78.2 | 7/12.7 | 5/9.1 | 106.2 ± 35.6 | 68.5 ± 34.7 | 42.2 ± 22.5 |

| Block | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n.cases | 1–5 | 6–10 | 11–15 | 16–20 | 21–25 | 26–30 | 31–35 | 36–40 | 41–45 | 46–50 | 51–55 |

| OP 1 m/SD | 110.7 ± 43.5 | 116.5 ± 18.3 | 85 ± 43.2 * | 91.5 ± 24.6 * | 88 ± 36.5 | 74 ± 23.3 * | 57 ± 31.9 * | 55 ± 10.9 * | 65 ± 21.8 | 84 ± 17.1 | 57.2 ± 26.8 |

| OP 2 m/SD | 122.7 ± 32.1 | 105 ± 31.4 | 140 ± 16.8 | 155 ± 39.4 | 113 ± 40.8 | 102 ± 42.1 | 119 ± 31.2 | 104 ± 49.2 | 61.2 ± 29.5 | 80 ± 18.7 | 74.25 ± 45.7 |

| Block | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n.cases | 1–5 | 6–10 | 11–15 | 16–20 | 21–25 | 26–30 | 31–35 | 36–40 | 41–45 | 46–50 | 51–55 |

| OP 1 m/SD | 35.5 ± 22.1 | 45.5 ± 27.7 | 42.6 ± 8.7 | 21.2 ± 3.9 * | 16.5 ± 6.4 * | 10.9 ± 8.7 * | 7.7 ± 11.4 * | 10.5 ± 5.6 * | 9.8 ± 7.9 | 12.3 ± 5.9 | 14.6 ± 2.2 |

| OP 2 m/SD | 42 ± 18.5 | 42.8 ± 26.2 | 40.8 ± 18.3 | 45.9 ± 18.3 | 33.1 ± 26.8 | 43.4 ± 6.4 | 27 ± 9.4 | 32.4 ± 18.5 | 7.4 ± 3.6 | 7.9 ± 3.2 | 22.6 ± 9.4 |

| Implant Duration | Predictor | r | Univariate β (95% CI) | p (uni) | Multivariate β (95% CI) | p (Multi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBBB ECG | 0.01 | 8.78 (−6.83 to 24.39) | 0.267 | 7.99 (−39.81 to 55.78) | 0.725 | |

| LVEDD (mm) | 0.43 | 0.86 (0.43 to 1.29) | <0.001 | 2.04 (−0.10 to 4.18) | 0.04 | |

| EF | −0.07 | −0.19 (−0.47 to 0.10) | 0.194 | 0.40 (−1.18 to 1.97) | 0.598 | |

| CRT/PM | 0.08 | 2.76 (−12.38 to 17.90) | 0.719 | −14.92 (−62.29 to 32.46) | 0.510 | |

| LLL | 0.25 | 23.52 (8.08 to 38.96) | 0.003 | 14.09 (−38.34 to 66.52) | 0.573 | |

| HBP/LBBPa | 0.09 | 25.25 (−7.98 to 58.48) | 0.131 | 13.54 (−78.66 to 105.74) | 0.757 | |

| Implant number | 0.36 | −1.07 (−1.51 to −0.63) | <0.001 | 3.26 (−1.57 to 6.49) | 0.04 | |

| Fluoroscopy time | Predictor | r | Univariate β (95% CI) | p (uni) | Multivariate β (95% CI) | p (multi) |

| LBBB ECG | 0.2 | 11.58 (0.71 to 22.45) | 0.037 | 0.55 (−35.82 to 36.93) | 0.974 | |

| LVEDD (mm) | 0.37 | 0.39 (0.10 to 0.68) | <0.001 | 2.01 (−0.37 to 3.39) | 0.04 | |

| EF | −0.07 | 0.01 (−0.19 to 0.21) | 0.927 | −0.06 (−1.24 to 1.12) | 0.917 | |

| CRT/PM | 0.08 | 6.68 (−3.78 to 17.14) | 0.207 | 7.63 (−22.09 to 37.34) | 0.584 | |

| LLL | 0.26 | 11.55 (1.08 to 22.01) | 0.031 | −9.44 (−43.23 to 24.35) | 0.551 | |

| HBP/LBBPa | 0.1 | 5.90 (−14.38 to 26.18) | 0.553 | 1.04 (−56.45 to 58.52) | 0.969 | |

| Implant number | 0.28 | −0.60 (−0.89 to −0.30) | <0.001 | −0.23 (−2.92 to 2.46) | 0.856 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santoro, A.; Baiocchi, C.; Collantoni, M.; Lunghetti, S.; Morrone, F.; Manetti, N.; Spaccaterra, L.; Petrini, A.; Taddeucci, S.; Fineschi, M. Assessing the Learning Curve in Conduction System Pacing Implantation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8684. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248684

Santoro A, Baiocchi C, Collantoni M, Lunghetti S, Morrone F, Manetti N, Spaccaterra L, Petrini A, Taddeucci S, Fineschi M. Assessing the Learning Curve in Conduction System Pacing Implantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8684. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248684

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantoro, Amato, Claudia Baiocchi, Maurizio Collantoni, Stefano Lunghetti, Francesco Morrone, Niccolò Manetti, Laura Spaccaterra, Alessia Petrini, Simone Taddeucci, and Massimo Fineschi. 2025. "Assessing the Learning Curve in Conduction System Pacing Implantation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8684. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248684

APA StyleSantoro, A., Baiocchi, C., Collantoni, M., Lunghetti, S., Morrone, F., Manetti, N., Spaccaterra, L., Petrini, A., Taddeucci, S., & Fineschi, M. (2025). Assessing the Learning Curve in Conduction System Pacing Implantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8684. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248684