Managing Complex Chronic Otitis Media: Insights from Subtotal Petrosectomy with Blind Sac Closure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

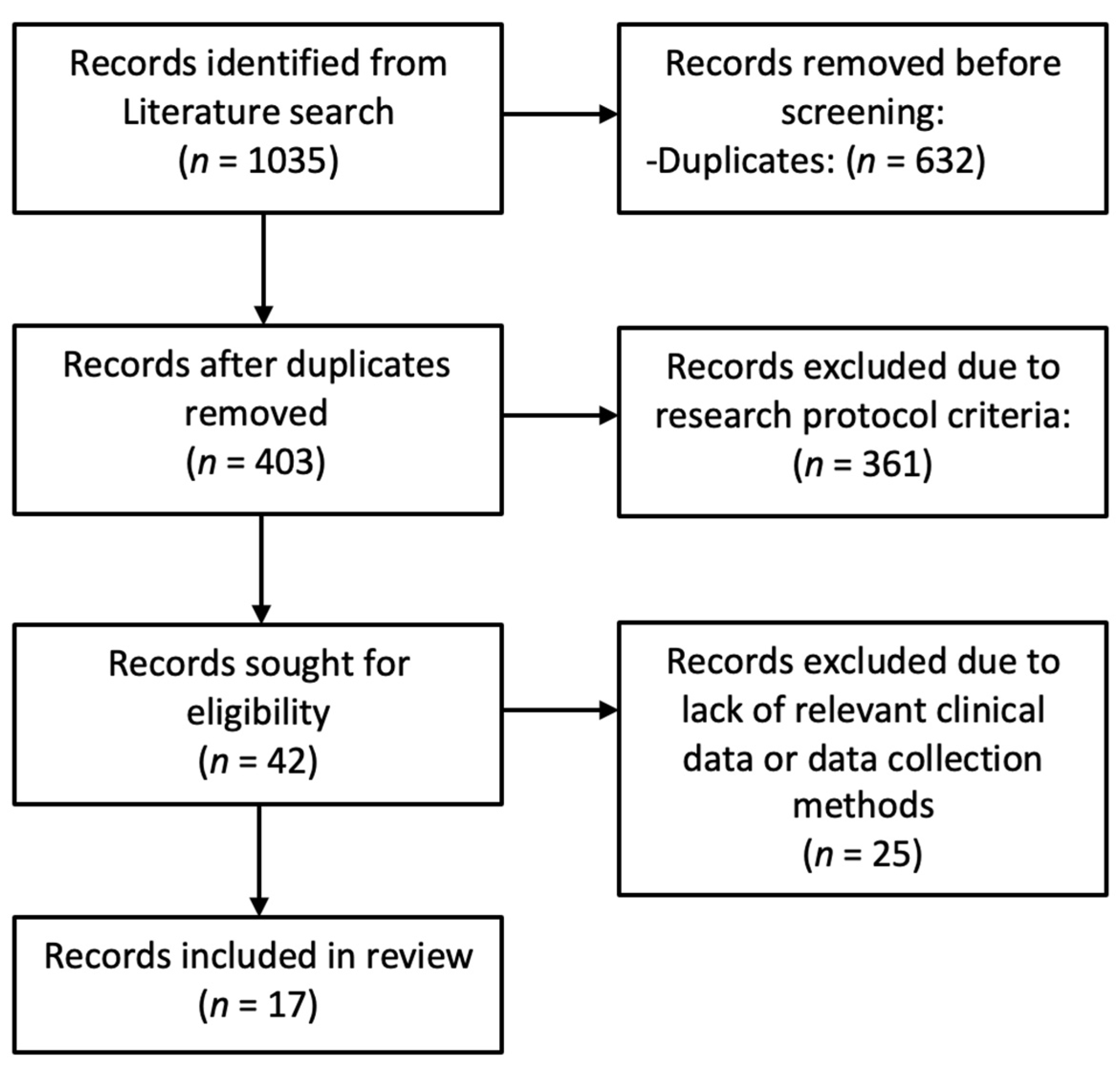

2.2. Literature Review

- -

- Population and inclusion criteria: Studies in the English language on patients of all ages, genders, and ethnicities with chronic or recurrent middle ear disease, with or without cholesteatoma, including those who had undergone previous surgical procedures.

- -

- Intervention: Studies in which patients underwent SP with BSC of the EAC with or without simultaneous procedures for bone-anchored hearing aids (BAHA), active middle ear implant (AMEI), middle ear transducer (MET), direct acoustic cochlear stimulator (DACS) or cochlear implant (CI).

- -

- Comparison and Outcome: The primary outcomes assessed were healing, failure, complications, and disease recurrence, making a comparison with our case series.

- -

- Timing: Studies published up to January 2023 have been included in this literature review.

- -

- Setting: Randomized controlled trials (RCT), non-randomized controlled trials (NRCT), prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and case–control studies from community, private, and tertiary care university hospitals were included.

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample

3.2. Literature Review

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| PICOTS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timing, and Setting |

| SP | Subtotal Petrosectomy |

| ET | Eustachian Tube |

| BSC | Blind Sac Closure |

| EAC | External Auditory Canal |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| SEMAC | Slice Encoded Metal Artifact Correction |

| MAVRIC | Multi-Acquisition Variable-Resonance Image Combination |

| CWD | Canal-Wall Down |

| FC | Fallopian Canal |

| CI | Cochlear Implant |

| BAHA | Bone-Anchored Hearing Aids |

| AMEI | Active Middle Ear Implants |

| MET | Middle Ear Transducer |

| DACS | Direct Acoustic Cochlear Stimulator |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| NRCT | Non-Randomized Controlled Trial |

References

- Prasad, S.C.; Roustan, V.; Piras, G.; Caruso, A.; Lauda, L.; Sanna, M. Subtotal petrosectomy: Surgical technique, indications, outcomes, and comprehensive review of literature. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immordino, A.; Sireci, F.; Lorusso, F.; Martines, F.; Dispenza, F. The Role of Cartilage-perichondrium Tympanoplasty in the Treatment of Tympanic Membrane Retractions: Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 26, e499–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambo, J.H. Musculoplasty: Advantages and disadvantages. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1965, 74, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, N.J.; Jenkins, H.A.; Fisch, U. Obliteration of the middle ear and mastoid cleft in subtotal petrosectomy: Indications, technique, and results. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1986, 95, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzador, D.; Franz, L.; Tealdo, G.; Carobbio, A.L.C.; Ferraro, M.; Mazzoni, A.; Marioni, G.; Zanoletti, E. Survival Outcomes in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the External Auditory Canal: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, M.; Dispenza, F.; Flanagan, S.; De Stefano, A.; Falcioni, M. Management of chronic otitis by middle ear obliteration with blind sac closure of the external auditory canal. Otol. Neurotol. 2008, 29, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, J.H. Primary closure of the radical mastoidectomy wound: A technique to eliminate postoperative care. Laryngoscope 1958, 68, 1216–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.H.; Crawford, G.B. An evaluation of the Rambo primary closure of the radical mastoidectomy wound. Trans. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 1960, 64, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Gacek, R.R. Mastoid and middle ear cavity obliteration for control of otitis media. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1976, 85, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L.J.; Sheehy, J.L. Total obliteration of the mastoid, middle ear, and external auditory canal. A review of 27 cases. Laryngoscope 1981, 91, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuknecht, H.F.; Chandler, J.R. Surgical obliteration of the tympanomastoid compartment and external auditory canal. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1984, 93, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.A.; Brookes, G.B. Subtotal petrosectomy with external canal overclosure in the management of chronic suppurative otitis media. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1994, 108, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.F.; Irving, R.M. Cochlear implants in chronic suppurative otitis media. Am. J. Otol. 1995, 16, 682–686. [Google Scholar]

- Kos, M.I.; Chavaillaz, O.; Guyot, J.P. Obliteration of the tympanomastoid cavity: Long term results of the Rambo operation. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2006, 120, 1014–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaert, N.; Mojallal, H.; Schwab, B. Indications and outcome of subtotal petrosectomy for active middle ear implants. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2013, 270, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Loan, F.L.; Lyon, J.R.; Bird, P.A. Blind sac closure of the external auditory canal for chronic middle ear disease. Otol. Neurotol. 2014, 35, e36–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliulo, G.; Turchetta, R.; Iannella, G.; Valperga di Masino, R.; de Vincentiis, M. Sophono Alpha System and subtotal petrosectomy with external auditory canal blind sac closure. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymański, M.; Ataide, A.; Linder, T. The use of subtotal petrosectomy in cochlear implant candidates with chronic otitis media. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, B.; Kludt, E.; Maier, H.; Lenarz, T.; Teschner, M. Subtotal petrosectomy and Codacs™: New possibilities in ears with chronic infection. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 1387–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyutenski, S.; Schwab, B.; Lenarz, T.; Salcher, R.; Majdani, O. Impact of the surgical wound closure technique on the revision surgery rate after subtotal petrosectomy. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 3641–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.; Hassannia, F.; Bergin, J.M.; Al Zaabi, K.; Rutka, J.A. Long-Term Outcomes from Blind Sac Closure of the External Auditory Canal: Our Institutional Experience in Different Pathologies. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2020, 16, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.B.; Chung, J.H.; Park, K.W.; Choi, J.W. Surgical outcomes of simultaneous cochlear implantation with subtotal petrosectomy. Auris Nasus Larynx 2020, 47, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasscock, M.E.; Poe, D.S.; Johnson, G.D.; Ragheb, S. Surgical management of the previously operated chronic ear. In Cholesteatoma and Mastoid Surgery; Tos, M., Thomsen, J., Peitersen, E., Eds.; Kugler and Ghedini Publications: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Berkeley, CA, USA; Milano, Italy, 1989; pp. 1027–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Immordino, A.; Salvago, P.; Sireci, F.; Lorusso, F.; Immordino, P.; Saguto, D.; Martines, F.; Gallina, S.; Dispenza, F. Mastoidectomy in surgical procedures to treat retraction pockets: A single-center experience and review of the literature. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2023, 280, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, J.H. A new operation to restore hearing in conductive deafness of chronic suppurative origin. AMA Arch. Otolaryngol. 1957, 66, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch, U. Infratemporal fossa approach for glomus tumors of the temporal bone. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1982, 91, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch, U.; Pillsbury, H.C. Infratemporal fossa approach to lesions in the temporal bone and base of skull. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1979, 105, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch, U. The infratemporal fossa approach for nasopharyngeal tumors. Laryngoscope 1983, 93, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, U.; Oldring, D.J.; Senning, A. Surgical therapy of internal carotid artery lesions of the skull base and temporal bone. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1980, 88, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyutenski, S.; El-Saied, S.; Schwab, B. Impact of occlusive material and cochlea-carotid artery relation on eustachian tube occlusion in subtotal petrosectomy. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2020, 5, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, A.; De Donato, G.; Piccirillo, E.; Leone, O.; Sanna, M. Petrous bone cholesteatoma: Management and outcomes. Laryngoscope 2006, 116, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, M.A.; Polanski, J.F.; Schlegel, C.; Linder, T. Active middle ear implants in patients undergoing subtotal petrosectomy: Long-term follow-up. Otol. Neurotol. 2014, 35, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanna, M.; Free, R.; Merkus, P.; Falcioni, M. Subtotal Petrosectomy in Cochlear Implantation Surgery for Cochlear and Other Auditory Implants; George Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Immordino, A.; Lorusso, F.; Sireci, F.; Dispenza, F. Acute pneumolabyrinth: A rare complication after cochlear implantation in a patient with obstructive sleep apnoea on CPAP therapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e254069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dispenza, F.; Immordino, A.; De Stefano, A.; Sireci, F.; Lorusso, F.; Salvago, P.; Martines, F.; Gallina, S. The prognostic value of subjective nasal symptoms and SNOT-22 score in middle ear surgery. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Side | Preoperative Otoscopy | Preoperative PTA | Previous Surgery | Other Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | M | Hearing loss, otorrhea, persistent infection | Right | Granulation tissue, squamous debris, secretions | NA | - | Autism |

| 2 | 28 | M | Hearing loss, otorrhea, persistent infection | Right | EAC stenosis, granulation tissue, squamous debris, secretions | NA | - | Autism |

| 3 | 36 | M | Hearing loss, otalgia, otorrhea, recurrent infection | Left | Granulation tissue, squamous debris, secretions | Severe CHL | - | - |

| 4 | 70 | F | Hearing loss, otorrhea, recurrent infection | Right | squamous debris, secretions | Severe CHL | Right CWD tympanoplasty | - |

| 5 | 60 | F | Hearing loss | Left | TM atelectasis | Profound SNHL | - | - |

| 6 | 44 | F | Hearing loss, otalgia, otorrhea, recurrent infection | Left | CSF leak, squamous debris | Severe CHL | Left CWD tympanoplasty | - |

| 7 | 53 | F | Hearing loss, otalgia, vertigo, otorrhea, persistent infection | Left | squamous debris, secretions | Anacusis | Left CWU tympanoplasty | EAC stenosis |

| 8 | 38 | M | Hearing loss, otalgia, otorrhea, persistent infection | Right | squamous debris, secretions | Anacusis | - | - |

| 9 | 46 | M | Hearing loss, vertigo, otorrhea, persistent infection | Right | Granulation tissue, squamous debris, secretions | Severe CHL | - | - |

| Case | Intraoperative Features | Intervention | Cavity Obliteration | ET Obliteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | SP + BSC | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 2 | Eroded incus | SP + BSC | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 3 | No stapes, no incus, eroded FC (tympanic tract) | SP + BSC | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 4 | - | SP + BSC + BAHA | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 5 | No stapes, no incus | SP + BSC + CI | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 6 | MCF dura exposed, Meningo-encephalic hernia | SP + BSC | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 7 | No stapes, fixed and eroded incus, eroded FC (tympanic tract), ASC and LSC fistulas | SP + BSC + CI | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 8 | - | SP + BSC + CI | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| 9 | Eroded stapes, no incus, eroded FC (2nd genu, tympanic tract, mastoid tract), exposed MCF and PCF dura, exposed SS, PSC, and LSC fistulas | SP + BSC | Abdominal fat | Cartilage + bone wax |

| Author | Cases (n of Ears) | Mean Age | Previous Surgery | Indications | Symptoms | Other Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rambo, J.H.T., 1958 [8] | 4 (4) | NA | NA | COM cholesteatoma (NA) | NA | Severe- profound SNHL (3) |

| Fritz, M.H. et al., 1960 [9] | 157 (157) | NA | NA | COM cholesteatoma (NA) | NA | NA |

| Gacek, R.R. et al., 1976 [10] | 6 (6) | 42 | 6 | COM cholesteatoma (3) | recurrent infections (5) CSF leak (2) otorrhea (1) | Severe- profound SNHL (5) |

| Bartels, L.J. et al., 1981 [11] | 24 (24) | NA | 23 | COM cholesteatoma (8) MET (2) | recurrent infections (16) otorrhea (6) otalgia (3) facial palsy (3) | Severe- profound SNHL (7) |

| Schuknecht, H.F. et al., 1984 [12] | 44 (44) | 40.5 | 30 | COM cholesteatoma (27) meningitis (1) | otorrhea (39) otalgia (11) facial palsy (9) vertigo (6) | EAC stenosis (11) Severe- profound SNHL (39) |

| Parikh, A.A. et al., 1994 [13] | 10 (10) | 43.8 | 10 | COM cholesteatoma (6) | recurrent infection (10) otorrhea (10) otalgia (2) facial palsy (1) | Severe- profound SNHL (7) |

| Gray, F. et al., 1995 [14] | 4 (4) | NA | 4 | COM cholesteatoma (2) | recurrent infection (2) otorrhea (2) | Severe- profound SNHL (4) |

| Kos, M.I. et al., 2006 [15] | 46 (46) | NA | 32 | COM cholesteatoma (32) | vertigo (11) facial palsy (3) | Severe- profound SNHL (46) |

| Sanna, M. et al., 2008 [6] | 53 (53) | 57 | 44 | COM cholesteatoma (43) | otorrhea (1) CSF leak (17) | EAC stenosis (8) Severe- profound SNHL (24) |

| Verahert, N. et al., 2013 [16] | 22 (22) | 57 | 22 | COM cholesteatoma (15) | otorrhea (8) | Severe- profound SNHL (22) |

| Patel, M. et al., 2014 [17] | 29 (32) | 54 | NA | COM cholesteatoma (21) | otorrhea (11) | Severe- profound SNHL (24) |

| Magliulo, G. et al., 2015 [18] | 10 (10) | 47.8 | 4 | COM cholesteatoma (1) | recurrent infections (9) otorrhea (6) | NA |

| Szymanski et al., 2016 [19] | 19 (19) | 54 | 7 | COM cholesteatoma (3) | otorrhea (6) | Severe- profound SNHL (19) |

| Schwab et al., 2016 [20] | 4 (4) | NA | 4 | COM cholesteatoma (0) | otorrhea (4) recurrent infections (4) | NA |

| Lyutenski et al., 2016 [21] | 199 (212) | 65 | 212 | COM cholesteatoma (NA) | NA | Severe- profound SNHL (101) |

| Kraus et al., 2020 [22] | 12 (12) | NA | 11 | COM cholesteatoma (2) | otorrhea (12) | NA |

| Lee et al., 2020 [23] | 25 (25) | 63.8 | NA | COM cholesteatoma (7) | otorrhea (13) | Severe- profound SNHL (25) |

| Author | Surgical Procedure | Intraoperative Features | Cavity Obliteration | ET Obliteration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rambo, J.H.T., 1958 [8] | SP + BSC (4) | NA | temporalis muscle flap | no |

| Fritz, M.H. et al., 1960 [9] | SP + BSC (157) | labyrinth fistula (2) | temporalis muscle flap | no |

| Gacek, R.R. et al., 1976 [10] | SP + BSC (6) | meningo-encephalic herniation (2) | abdominal fat + soft tissue | no |

| Bartels, L.J. et al., 1981 [11] | SP + BSC (24) | NA | abdominal fat, temporalis muscle fascia, bone paté, Palva flap | no |

| Schuknecht, H.F. et al., 1984 [12] | SP + BSC (44) | abscess (1) meningo-encephalic herniation (3) labyrinth fistula (9) LSC dehiscence (17) | abdominal fat, free muscle, muscle flap, myocutaneous flap | cartilage |

| Parikh, A.A. et al., 1994 [13] | SP + BSC (10) | labyrinth fistula (3) | abdominal fat | bone paté, bone wax, oxidized regenerated cellulose |

| Gray, F. et al., 1995 [14] | SP + BSC + CI (4) | NA | abdominal fat + temporalis muscle fascia | NA |

| Kos, M.I. et al., 2006 [15] | SP + BSC (46) | NA | abdominal fat | cartilage |

| Sanna, M. et al., 2008 [6] | SP + BSC (53) | exposed dura mater (36) meningo-encephalic herniation (30) eroded FC (18) labyrinth fistula (14) | abdominal fat | bone wax |

| Verahert, N. et al., 2013 [16] | SP + BSC (4) SP + BSC + CI (2) SP + BSC + AMEI (16) | NA | abdominal fat + periosteal flap | bone wax + oxidized regenerated cellulose |

| Patel, M. et al., 2014 [17] | SP + BSC (24) SP + BSC + CI (6) SP + BSC + BAHA (2) | NA | temporalis muscle flap + temporalis muscle fascia + periosteal flap | temporal muscle |

| Magliulo, G. et al., 2015 [18] | SP + BSC + BAHA (10) | meningo-encephalic herniation (1) | abdominal fat + periosteal flap | bone wax + temporal muscle |

| Szymanski et al., 2016 [19] | SP + BSC + CI (19) | eroded FC (1) | abdominal fat + temporalis muscle flap | bone wax |

| Schwab et al., 2016 [20] | SP + BSC + DACS (4) | NA | abdominal flap | NA |

| Lyutenski et al., 2016 [21] | SP + BSC (43) SP + BSC + CI (101) SP + BSC + AMEI (57) SP + BSC + MET (7) SP + BSC + DACS (4) | NA | abdominal fat + periosteal flap, abdominal fat + periosteal flap + temporalis muscle fascia + temporalis muscle flap, abdominal fat + polydioxanone/allogenic fascia/bovine pericardium | bone wax + oxidized regenerated cellulose |

| Kraus et al., 2020 [22] | SP + BSC (12) | NA | abdominal fat, fibrin glue | periosteum, cartilage |

| Lee et al., 2020 [23] | SP + BSC + CI (25) | NA | abdominal fat, temporalis muscle flap | bone wax, soft tissue, fibrin glue |

| Author | Postoperative Complications % (n) | Delayed Complications % (n) | Failure % (n) | Reinterventions % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rambo, J.H.T., 1958 [8] | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | NA |

| Fritz, M.H. et al., 1960 [9] | 0% (0) | recurrent cholesteatoma 3.8% (6) | 0% (0) | NA |

| Gacek, R.R. et al., 1976 [10] | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Bartels, L.J. et al., 1981 [11] | infection 12.5% (3) SNHL 8.3% (2) | recurrent infection 8.3% (2) recurrent cholesteatoma 4.2% (1) delayed facial palsy 4.2% (1) | 4.2% (1) | 16.7% (4) |

| Schuknecht, H.F. et al., 1984 [12] | infection 20.4% (9) vertigo 9% (4) seroma 6.8% (3) hematoma of donor site 4.5% (2) incisional granulation 2.3% (1) transient facial palsy 2.3% (1) | recurrent cholesteatoma 6.8% (3) delayed facial palsy 2.3% (1) | NA | 11.4% (5) |

| Parikh, A.A. et al., 1994 [13] | infection 30% (3) vertigo 20% (2) | delayed facial palsy 20% (2) | 0% (0) | 30% (3) |

| Gray, F. et al., 1995 [14] | 0% (0) | recurrent cholesteatoma 25% (1) | 0% (0) | NA |

| Kos, M.I. et al., 2006 [15] | infection 17.4% (8) | recurrent cholesteatoma 8.7% (4) recurrent infection 2.2% (1) | 1 (2.2%) | 23.9% (11) |

| Sanna, M. et al., 2008 [6] | SNHL 9.4% (5) post-aural fistula 1.9% (1) | recurrent cholesteatoma 1.9% (1) residual cholesteatoma 1.9% (1) | 0% (0) | 3.8% (2) |

| Verahert, N. et al., 2013 [16] | wound dehiscence 18.2% (4) transient facial palsy 4.5% (1) hematoma of the donor site 4.5% (1) | 0% (0) | 13.6% (3) | 13.6% (3) |

| Patel, M. et al., 2014 [17] | infection 25% (8) incisional granulation 3.1% (1) wound dehiscence 3.1% (1) seroma 3.1% (1) | recurrent cholesteatoma 15.6% (5) residual cholesteatoma 15.6% (5) | 0% (0) | 15.6% (5) |

| Magliulo, G. et al., 2015 [18] | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Szymanski et al., 2016 [19] | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Schwab et al., 2016 [20] | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Lyutenski et al., 2016 [21] | infection 1.4% (3) wound dehiscence 16% (34) | entrapped cholesteatoma 2.4% (5) CI extrusion 0.5% (1) | 0% (0) | 16% (34) |

| Kraus et al., 2020 [22] | wound dehiscence 40% (3) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 40% (3) |

| Lee et al., 2020 [23] | wound dehiscence 4% (1) | CI extrusion 8% (2) | 0% (0) | 12% (3) |

| Our series | vertigo 11.1% (1) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Immordino, A.; Oliva, S.; Immordino, P.; Sireci, F.; Lorusso, F.; Manzella, R.; Gallina, S.; Maniaci, A.; Iannella, G.; Mat, Q.; et al. Managing Complex Chronic Otitis Media: Insights from Subtotal Petrosectomy with Blind Sac Closure. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8633. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248633

Immordino A, Oliva S, Immordino P, Sireci F, Lorusso F, Manzella R, Gallina S, Maniaci A, Iannella G, Mat Q, et al. Managing Complex Chronic Otitis Media: Insights from Subtotal Petrosectomy with Blind Sac Closure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(24):8633. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248633

Chicago/Turabian StyleImmordino, Angelo, Simone Oliva, Palmira Immordino, Federico Sireci, Francesco Lorusso, Riccardo Manzella, Salvatore Gallina, Antonino Maniaci, Giannicola Iannella, Quentin Mat, and et al. 2025. "Managing Complex Chronic Otitis Media: Insights from Subtotal Petrosectomy with Blind Sac Closure" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 24: 8633. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248633

APA StyleImmordino, A., Oliva, S., Immordino, P., Sireci, F., Lorusso, F., Manzella, R., Gallina, S., Maniaci, A., Iannella, G., Mat, Q., & Dispenza, F. (2025). Managing Complex Chronic Otitis Media: Insights from Subtotal Petrosectomy with Blind Sac Closure. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(24), 8633. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14248633