Spinal Cord Stimulation: Mechanisms of Action, Indications, Types, Complications

Abstract

1. Introduction

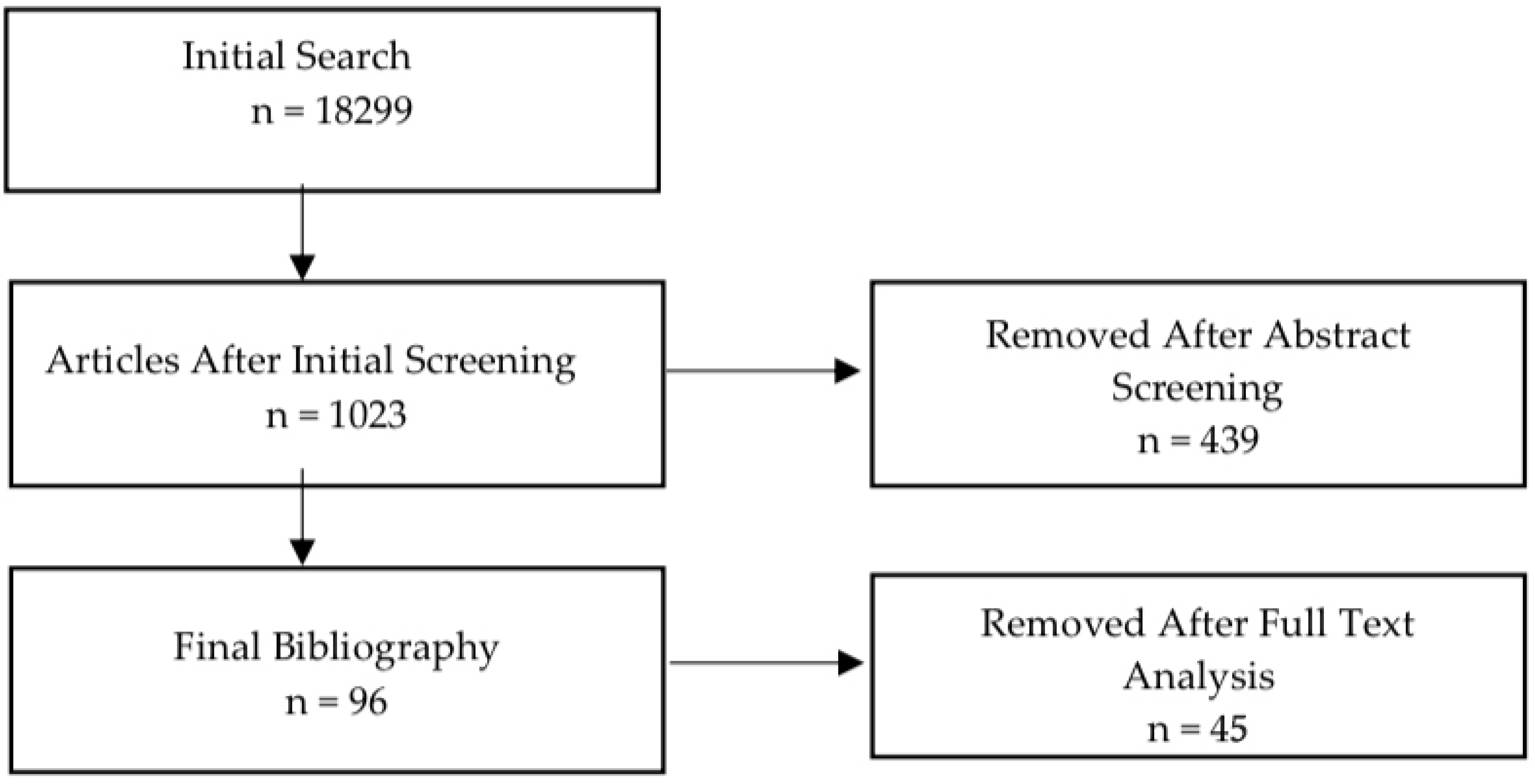

2. Methods

3. Gate Control Theory of Pain and Modern Mechanisms

4. Spinal Cord Stimulation Physiology, Anatomy, Neurotransmitters and Mechanism

4.1. Spinal Segmental Physiology Mechanism

4.2. Supraspinal Physiology Mechanism

4.3. Descending Pathways and Neurotransmitters

5. Indications and Contraindications

6. Types of Stimulation

6.1. Traditional Spinal Cord Stimulation

6.2. Tonic Stimulation

6.3. High-Frequency Stimulation

6.4. Burst Stimulation

6.5. Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation

6.6. DTM Spinal Cord Stimulation

6.7. High-Density Spinal Cord Stimulation

7. SCS and Complications

8. Discussion

9. Perspectives and Limitations

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCS | Spinal Cord Stimulation |

| PSPS | Spinal Pain Syndrome |

| CRPS | Complex Regional Pain Syndrome |

| SCI | Cervical Spinal Cord Injury |

| HFS | High-Frequency Stimulation |

| DRGS | Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation |

| DRG | Dorsal Root Ganglion |

| DTM | Differential Target Multiplexed |

| HD | High-Density |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

References

- Guzzi, G.; Torre, A.D.; La Torre, D.; Volpentesta, G.; Stroscio, C.A.; Lavano, A.; Longhini, F. Spinal cord stimulation in chronic low back pain syndrome: Mechanisms of modulation, technical features and clinical application. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, H.; van Kleef, M.; Holsheimer, J.; Joosten, E.A.J. Experimental spinal cord stimulation and neuropathic pain: Mechanism of action, technical aspects, and effectiveness. Pain Pract. 2013, 13, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shealy, C.N.; Mortimer, J.T.; Reswick, J.B. Electrical inhibition of pain by stimulation of the dorsal columns: Preliminary clinical report. Anesth. Analg. 1967, 46, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.L.; Li, J.; Xu, H.C.; Liu, Y.C.; Yang, T.T.; Yuan, H. Progress in the efficacy and mechanism of spinal cord stimulation in neuropathological pain. iBrain 2022, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Carayannopoulos, A.G. Spinal cord stimulation: The use of neuromodulation for treatment of chronic pain. Rhode Isl. Med. J. 2020, 103, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heitler, B. Primary afferent depolarization and the gate control theory of pain: A tutorial simulation. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 2023, 22, A58–A65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.L.; Johanek, L.M.; Sanada, L.S.; Sluka, K.A. Spinal cord stimulation reduces mechanical hyperalgesia and glial cell activation in animals with neuropathic pain. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 118, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Peng, C.; Joosten, E.; Cheung, C.W.; Tan, F.; Jiang, W.; Shen, X. Spinal cord stimulation and treatment of peripheral or central neuropathic pain: Mechanisms and clinical application. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 5607898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, E.; Kurt, K.N.; Yousem, D.M.; Christo, P.J. Spinal cord stimulators: Typical positioning and postsurgical complications. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 196, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.P.; Nicolelis, M.A.L. Electrical stimulation of the dorsal columns of the spinal cord for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dones, I.; Levi, V. Spinal cord stimulation for neuropathic pain: Current trends and future applications. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwald, M.; Gulisano, H.A.; Bjarkam, C.R. Spinal cord stimulation in complex regional pain syndrome type 2. Dan. Med. J. 2022, 69, A06210521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Eijs, F.; Stanton-Hicks, M.; van Zundert, J.; Faber, C.G.; Lubenow, T.R.; Mekhail, N.; van Kleef, M.; Huygen, F. 16. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain Pract. 2011, 11, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzman, B.T.; Provenzano, D.A. Best practices in spinal cord stimulation. Spine 2017, 42 (Suppl. S14), S67–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapural, L.; Yu, C.; Doust, M.W.; Gliner, B.E.; Vallejo, R.; Sitzman, B.T.; Amirdelfan, K.; Morgan, D.M.; Brown, L.L.; Yearwood, T.L.; et al. Novel 10-kHz High-Frequency Therapy (HF10 Therapy) Is Superior to Traditional Low-Frequency Spinal Cord Stimulation for the Treatment of Chronic Back and Leg Pain: The SENZA-RCT Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Breitbart, S.; Malvea, A.; Bhatia, A.; Ibrahim, G.M.; Gorodetsky, C. Epidural spinal cord stimulation for spasticity: A systematic review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2024, 183, 227–238.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, A.; Sperry, B.P.; Cheney, C.W.; Burnham, T.M.; Mahan, M.A.; Onofrei, L.V.; Cushman, D.M.; Wagner, G.E.; Shipman, H.; Teramoto, M.; et al. The effectiveness of spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of axial low back pain: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. In Pain Medicine (United States); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; Volume 21, pp. 2699–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirketeig, T.; Schultheis, C.; Zuidema, X.; Hunter, C.W.; Deer, T. Burst Spinal Cord Stimulation: A Clinical Review. Pain Med. 2019, 20, S31–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S. Health-related quality of life and spinal cord stimulation in painful diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 206, 110826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, B.L.; Bao, J.; Khazen, O.; Pilitsis, J.G. Spinal cord stimulation as treatment for cancer and chemotherapy-induced pain. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 699993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Munglani, R.; Eyre, G.; Bajaj, G.; Abd-Elsayed, A.; Poply, K. Consenting for spinal cord stimulation—The pitfalls and solution. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2025, 29, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, S.; Garcia, J.; Cowley, K.C. Spinal electrical stimulation to improve sympathetic autonomic functions needed for movement and exercise after spinal cord injury: A scoping clinical review. J. Neurophysiol. 2022, 128, 649–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, V.; Bizzell, C.; Obray, R.; Obray, J.; Lamer, T.; Carrino, J.A. Spinal cord stimulation: The types of neurostimulation devices currently being used, and what radiologists need to know when evaluating their appearance on imaging. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2010, 39, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camporeze, B.; Simm, R.; Maldaun, M.; de Aguiar, P.P. Spinal cord stimulation in pregnant patients: Current perspectives of indications, complications, and results in pain control: A systematic review. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2019, 14, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, K.; Glavind, J.; Milidou, I.; Sørensen, J.C.H.; Sandager, P. Burst spinal cord stimulation in pregnancy: First clinical experiences. Neuromodulation 2023, 26, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isagulyan, E.; Tkachenko, V.; Semenov, D.; Asriyants, S.; Dorokhov, E.; Makashova, E.; Aslakhanova, K.; Tomskiy, A. The effectiveness of various types of electrical stimulation of the spinal cord for chronic pain in patients with postherpetic neuralgia: A literature review. Pain Res. Manag. 2023, 2023, 6015680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrills, P.; Sinclair, C.; Barnard, A. A review of spinal cord stimulation systems for chronic pain. J. Pain. Res. 2016, 9, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedade, G.S.; Gillner, S.; Slotty, P.J.; Vesper, J. Combination of waveforms in modern spinal cord stimulation. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdrulla, A.D.; Guan, Y.; Raja, S.N. Spinal cord stimulation: Clinical efficacy and potential mechanisms. Pain Pract. 2018, 18, 1048–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, K.; Fishman, M.A.; Zuidema, X.; Hunter, C.W.; Levy, R. Mechanism of action in burst spinal cord stimulation: Review and recent advances. Pain Med. 2019, 20 (Suppl. S1), S13–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, D.; Plazier, M.; Kamerling, N.; Menovsky, T.; Vanneste, S. Burst spinal cord stimulation for limb and back pain. World Neurosurg. 2013, 80, 642–649.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, G.C.C.; Mekhail, N. Alternate intraspinal targets for spinal cord stimulation: A systematic review. Neuromodulation 2017, 20, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, M.A.; Cordner, H.; Justiz, R.; Provenzano, D.; Merrell, C.; Shah, B.; Naranjo, J.; Kim, P.; Calodney, A.; Carlson, J.; et al. Twelve-month results from multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled clinical trial comparing differential target multiplexed spinal cord stimulation and traditional spinal cord stimulation in subjects with chronic intractable back pain and leg pain. Pain Pract. 2021, 21, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.Z.; Fishman, M.A. Differential Target Multiplexed Spinal Cord Stimulator: A review of preclinical/clinical data and hardware advancement. Pain Manag. 2023, 13, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallewaard, J.W.; Billet, B.; Van Paesschen, R.; Smet, I.; Mendiola, A.; Pena, I.; Lopez, P.; Carceller, J.; Tornero, C.; Zuidema, X.; et al. European randomized controlled trial evaluating differential target multiplexed spinal cord stimulation and conventional medical management in subjects with persistent back pain ineligible for spine surgery: 24-month results. Eur. J. Pain 2024, 28, 1745–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, F.; Breel, J.S.; Bakker, E.W.; Hollmann, M.W. Altering Conventional to High Density Spinal Cord Stimulation: An Energy Dose-Response Relationship in Neuropathic Pain Therapy. Neuromodulation 2017, 20, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Poply, K.; Ahmad, A.; Lascelles, J.; Elyas, A.; Sharma, S.; Ganeshan, B.; Ellamushi, H.; Nikolic, S. Effectiveness of high dose spinal cord stimulation for non-surgical intractable lumbar radiculopathy-HIDENS Study. Pain Physician 2022, 22, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labaran, L.; Jain, N.; Puvanesarajah, V.; Jain, A.; Buchholz, A.L.; Hassanzadeh, H. A retrospective database review of the indications, complications, and incidence of subsequent spine surgery in 12,297 spinal cord stimulator patients. Neuromodulation 2020, 23, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiabadi, M.M.; Vicheva, P.; Unterberg, A.; Ahmadi, R.; Jakobs, M. A single-center, open-label trial on convenience and complications of rechargeable implantable pulse generators for spinal cord stimulation: The Recharge Pain Trial. Neurosurg. Rev. 2023, 46, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendersky, D.; Yampolsky, C. Is spinal cord stimulation safe? A review of its complications. World Neurosurg. 2014, 82, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Schwalb, J.M. History and future of spinal cord stimulation. Neurosurgery 2024, 94, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendel, M.A.; O’Brien, T.; Hoelzer, B.C.; Deer, T.R.; Pittelkow, T.P.; Costandi, S.; Walega, D.R.; Azer, G.; Hayek, S.M.; Wang, Z.; et al. Spinal Cord Stimulator Related Infections: Findings From a Multicenter Retrospective Analysis of 2737 Implants. Neuromodulation 2017, 20, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.M.P.; Shaheed, C.A.; Ferreira, G.; Mannix, L.; Harris, I.A.; Buchbinder, R.; Maher, C.G. Spinal Cord Stimulators: An Analysis of the Adverse Events Reported to the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration. 2022. Available online: http://links.lww.com/JPS/A450 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Jenkinson, R.H.; Wendahl, A.; Zhang, Y.; Sindt, J.E. Migration of Epidural Leads During Spinal Cord Stimulator Trials. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 2999–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammartino, F.; MacDonell, J.; North, R.B.; Krishna, V.; Poree, L. Disease applications of spinal cord stimulation: Chronic nonmalignant pain. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21, e00314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, K.V. Spinal stimulation for pain: Future applications. Neurotherapeutics 2014, 11, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opova, K.; Limousin, P.; Akram, H. Spinal cord stimulation for gait disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J. Park. Dis. 2023, 13, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, V.; Kaizer, A.; Patwardhan, A.M.; Ibrahim, M.; De Simone, D.C.; Sivanesan, E.; Shankar, H. Postoperative oral antibiotic use and infection-related complications after spinal cord stimulator surgery. Neuromodulation 2022, 25, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhail, N.A.; Levy, R.M.; Deer, T.R.; Kapural, L.; Li, S.; Amirdelfan, K.; Pope, J.E.; Hunter, C.W.; Rosen, S.M.; Costandi, S.J.; et al. ECAP-controlled closed-loop versus open-loop SCS for the treatment of chronic pain: 36-month results of the EVOKE blinded randomized clinical trial. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2024, 49, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, L.; Pope, J.; Verrills, P.; Petersen, E.; Kallewaard, J.W.; Gould, I.; Karantonis, D.M. First evidence of a biomarker-based dose-response relationship in chronic pain using physiological closed-loop spinal cord stimulation. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025, 50, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indication/Condition | Notes |

|---|---|

| Persistent spinal pain syndrome (PSPS) without neurological deterioration | Common indication; SCS effective if no progressive neuro deficits |

| Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) Types I and II | Widely accepted application of SCS |

| Radicular and nerve root pain | SCS useful in nerve root syndromes |

| Axial low back pain | High-frequency SCS recommended in refractory cases |

| Non-reconstructable critical limb ischemia | Better limb salvage compared to sympathectomy |

| Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy | Effective when medications are ineffective or poorly tolerated |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | Effectiveness may correlate inversely with deafferentation level |

| Peripheral nerve injury-related pain | SCS as an alternative in treatment-resistant pain |

| Intercostal neuralgia | Positive response reported in clinical use |

| Phantom limb pain | Common target for neuromodulation |

| Visceral pain (case-by-case) | Used selectively; individualized approach |

| Central neuropathic pain (segmental, SCI-related) | Localized segmental pain may respond to SCS |

| Chronic cancer-related pain (favorable prognosis) | Considered when disease progression is slow/remission likely |

| Autonomic/metabolic dysfunction (SCI-related) | Improves BP, thermoregulation, metabolism, and motor/autonomic functions |

| Absolute Contraindications | Relative Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Persistent or surgically correctable spinal cord/nerve root compression identified on imaging | Diagnostic uncertainty regarding neuropathic vs. non-neuropathic pain mechanisms |

| Severe, uncontrolled psychiatric conditions (e.g., untreated major depression, psychosis) | Stable psychiatric conditions requiring further optimization before implantation |

| Active substance abuse or addiction | History of substance misuse currently under control |

| Active infection at surgical site or systemic infection | Increased infection risk due to immunosuppression, poor wound healing, or comorbidities |

| Inability to undergo required imaging or surgery | High perioperative risk associated with medical comorbidities |

| SCS Modality | Modulated Pathways/Mechanisms |

|---|---|

| Tonic Stimulation | Paresthesia-based mechanism primarily driven by activation of large Aβ dorsal column axons, resulting in downstream modulation of dorsal column–mediated sensory signaling. |

| High-Frequency Stimulation (HF10) | Produces analgesia through mechanisms that may include inhibition of axonal conduction, reversible conduction block of dorsal column axons and glial–neuronal signaling modulation. The precise mechanistic basis remains under active debate. |

| Burst Stimulation | Modulates spinal dorsal horn activity through non-GABAergic pathways; associated with increased IL-10 levels in CSF and systemic circulation (anti-inflammatory analgesia). Promoting nerve fiber regeneration. Modulation of supraspinal pain-processing centers. |

| Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation (DRGS) | Activation of Aβ-, Aδ-, and C-fibers. Enables pain inhibition through opioid receptor activation with minimal GABAergic involvement. Induces C-fiber membrane hyperpolarization via calcium-activated potassium channels in the T-junctions, blocking propagation of nociceptive signals into the CNS. |

| Differential Target Multiplexed (DTM) Stimulation | Delivers multiple synchronized electrical signals designed to restore homeostatic balance between neuronal and glial populations, targeting neuroimmune dysregulation implicated in chronic pain. |

| Complication Type | Specific Complications | Notes/Approximate Incidence Range |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious | Infection (pulse generator pocket, dorsal incision site) Epidural infection | Infections can spread into the epidural space; prompt management is critical. Incidence: 4.3% |

| Hemorrhagic | Neuraxial hematoma Subcutaneous hematoma Hemorrhage | Neuraxial hematoma may cause spinal cord compression or cauda equina syndrome; subcutaneous bleeding may occur during pocket formation. Incidence: 0.5% |

| Neurological | Dural puncture → CSF leak Traumatic neuraxial injury Spinal cord or cauda equina compression | Can result in serious complications such as irreversible deficits or paralysis |

| Mechanical/Device-related | Lead migration Lead fracture Electrode displacement | Lead migration alters paresthesia coverage; lead fracture may result in complete loss of stimulation. Incidence: 3.4% |

| Allergic/Immune | Contact dermatitis Allergic reaction | Rare, but possible response to implanted materials |

| Wound Healing | Seroma Wound dehiscence Incisional pain | Usually self-limiting; may delay recovery. Incidence: 0.4% |

| Vascular | Thrombosis | Rare but possible during implantation |

| Other | Adverse hardware reactions Discomfort at implantable pulse generator site | Hardware-related reactions are exceedingly rare; postoperative discomfort is typically transient. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vlachou, C.; Sarridou, D.; Grosomanidis, V.; Voulgaris, I.; Argiriadou, H.; Amaniti, A. Spinal Cord Stimulation: Mechanisms of Action, Indications, Types, Complications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238615

Vlachou C, Sarridou D, Grosomanidis V, Voulgaris I, Argiriadou H, Amaniti A. Spinal Cord Stimulation: Mechanisms of Action, Indications, Types, Complications. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238615

Chicago/Turabian StyleVlachou, Chrysoula, Despoina Sarridou, Vasilios Grosomanidis, Ilias Voulgaris, Helena Argiriadou, and Aikaterini Amaniti. 2025. "Spinal Cord Stimulation: Mechanisms of Action, Indications, Types, Complications" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238615

APA StyleVlachou, C., Sarridou, D., Grosomanidis, V., Voulgaris, I., Argiriadou, H., & Amaniti, A. (2025). Spinal Cord Stimulation: Mechanisms of Action, Indications, Types, Complications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238615