Artificial Intelligence Physician Avatars for Patient Education: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Significance

1.3. Objective

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Development of the Surgeon Avatar and Study Procedures

2.3. Outcome Measures

- Engagement: Seven items from the User Engagement Scale-Short Form, assessing visual appeal, absorption, and value [17].

- Acceptability/Trust: Ten items from digital health scales, focusing on trustworthiness, credibility, and recommendation willingness [12].

- Eeriness/Discomfort: Five items from the uncanny valley literature, assessing unease, visual distortions, and audio-visual mismatch [18].

2.4. Data Analysis and Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Metrics Analysis

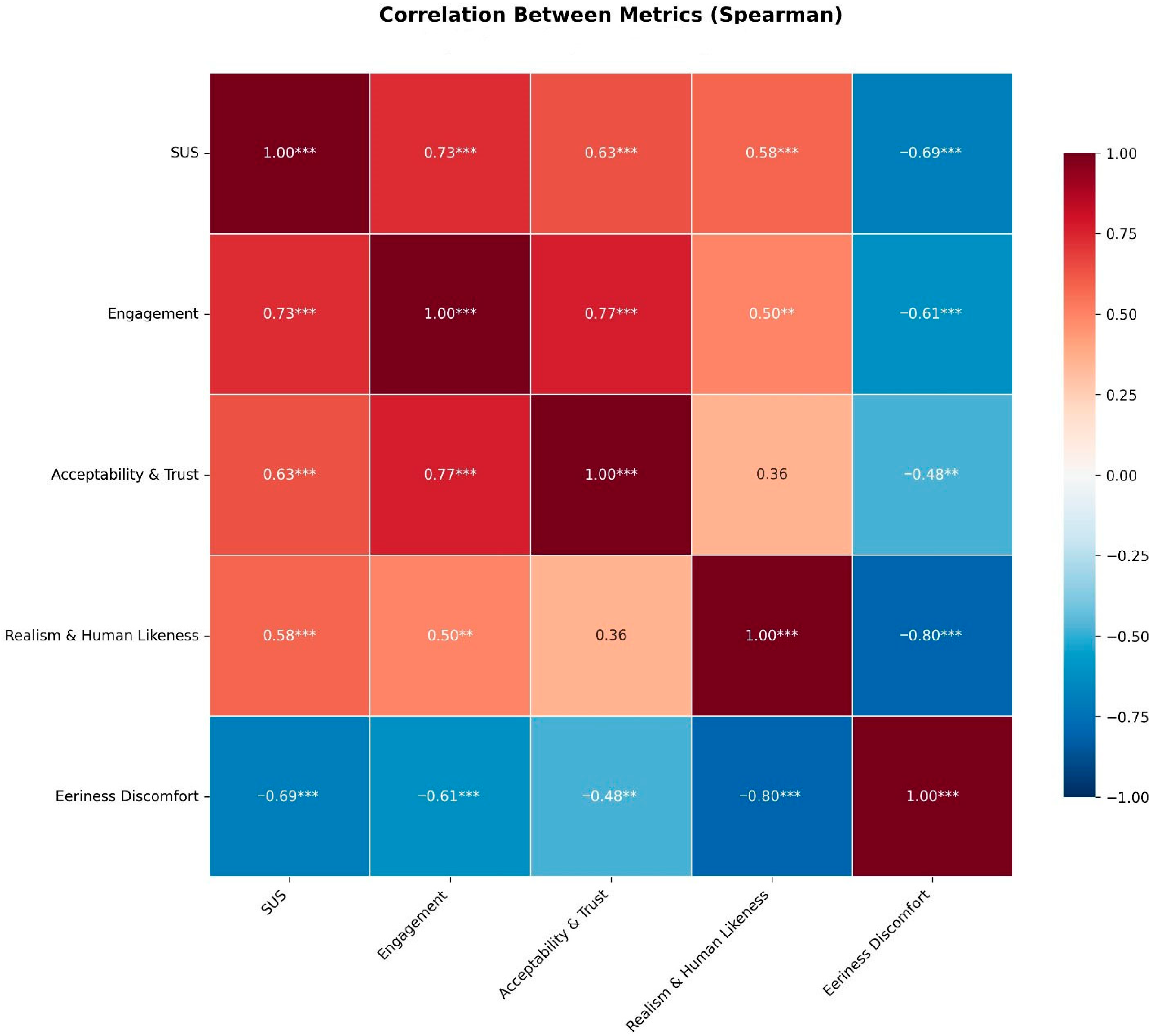

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Qualitative/Thematic Analysis

- Theme 1: Communication Effectiveness (Most Prominent)

- Theme 2: Human-Like Interaction Quality

- Theme 3: Technical Limitations

- Theme 4: Content Scope and Personalization

- Theme 5: Usability and Accessibility

4. Discussion

4.1. Beyond the Uncanny Valley

4.2. Familiarity as an Antidote to the Uncanny Valley

4.3. Trust Through Transparency

4.4. Avatars in Healthcare as a Tool

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

4.6. Future Research

4.7. Ethical Concerns

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loiperdinger, M.; Elzer, B. Lumière’s arrival of the train: Cinema’s founding myth. Mov. Image 2004, 4, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.M. Paper Promises: Early American Photography; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Strother, Z.S. ‘A Photograph Steals the Soul’: The History of an Idea. In Portraiture and Photography in Africa; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 2013; pp. 177–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, A.; Mohanty, S.P.; Kougianos, E. The world of generative ai: Deepfakes and large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.04373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.A.; Prabha, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Borna, S.; Genovese, A.; Trabilsy, M.; Collaco, B.G.; Wood, N.G.; Bagaria, S.; Tao, C. Synthetic Patient–Physician Conversations Simulated by Large Language Models: A Multi-Dimensional Evaluation. Sensors 2025, 25, 4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, Z. Deepfakes generation and detection: A short survey. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Martínez, O.; Fernández-García, D.; Cuartero Monteagudo, N.; Forero-Rincón, O. Possible health benefits and risks of deepfake videos: A qualitative study in nursing students. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2746–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruiter, A. The distinct wrong of deepfakes. Philos. Technol. 2021, 34, 1311–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Létourneau, A.; Deslandes Martineau, M.; Charland, P.; Karran, J.A.; Boasen, J.; Léger, P.M. A systematic review of AI-driven intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) in K-12 education. npj Sci. Learn 2025, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Tiefenbach, J.; Demetriades, A.K. The role of artificial intelligence in surgical simulation. Front. Med. Technol. 2022, 4, 1076755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Borna, S.; Pressman, S.; Haider, S.A.; Haider, C.R.; Forte, A.J. Artificial-Intelligence-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Primary Care: A Scoping Review of Current Clinical Implementations. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, S.; Wadley, G.; Bird, D.; Oldenburg, B.; Speight, J.; The My Diabetes Coach Research Group. Acceptability of an embodied conversational agent for type 2 diabetes self-management education and support via a smartphone app: Mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Catherine, T.Y.; Hinson, C.; Fung, E.; Allam, O.; Nazerali, R.S.; Ayyala, H.S. ChatGPT virtual assistant for breast reconstruction: Assessing preferences for a traditional Chatbot versus a human AI VideoBot. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garety, P.A.; Edwards, C.J.; Jafari, H.; Emsley, R.; Huckvale, M.; Rus-Calafell, M.; Fornells-Ambrojo, M.; Gumley, A.; Haddock, G.; Bucci, S. Digital AVATAR therapy for distressing voices in psychosis: The phase 2/3 AVATAR2 trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Lynch, C.; Worlikar, H.; Kelly, E.; Loveys, K.; Simpkin, A.J.; Walsh, J.C.; Broadbent, E.; Finucane, F.M.; O’Keeffe, D. “Digital Clinicians” Performing Obesity Medication Self-Injection Education: Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Diabetes 2025, 10, e63503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, M.K.; Khamwan, K.; Carrion, D. A pilot study of generative AI video for patient communication in radiology and nuclear medicine. Health Technol. 2025, 15, 395–404. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Lucas, M.; Bem-haja, P.; Pedro, L. AI versus human-generated voices and avatars: Rethinking user engagement and cognitive load. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 22547–22566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Kim, S.J.; Biocca, F. The uncanny valley: No need for any further judgments when an avatar looks eerie. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 94, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalake, M. Doctors’ perceptions of using their digital twins in patient care. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, J.; Perkins, M.; Somoray, K.; Miller, D.; Furze, L. To Deepfake or Not to Deepfake: Higher Education Stakeholders’ Perceptions and Intentions towards Synthetic Media. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.W.; Shin, M. Uncanny valley effects on chatbot trust, purchase intention, and adoption intention in the context of e-commerce: The moderating role of avatar familiarity. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doraiswamy, S.; Abraham, A.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etienne, D.; Archambault, P.; Aziaka, D.; Chipenda-Dansokho, S.; Dubé, E.; Fallon, C.S.; Hakim, H.; Kindrachuk, J.; Krecoum, D.; MacDonald, S.E. A personalized avatar-based web application to help people understand how social distancing can reduce the spread of COVID-19: Cross-sectional, observational, pre-post study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e38430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, N. Dr. Oz Promotes AI Avatars in 1st Meeting as CMS Chief. 2025. Available online: https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/healthcare-information-technology/ai/dr-oz-promotes-ai-avatars-in-first-meeting-as-cms-chief/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- He, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, N.; Sun, G. The first birthday of OpenAI’s Sora: A promising but cautious future in medicine. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 4151–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsah, M.-H.; Nazer, R.; Altamimi, I.; Aldekhyyel, R.; Jamal, A.; Almansour, M.; Aljamaan, F.; Alhasan, K.; Temsah, A.A.; Al-Eyadhy, A. OpenAI’s sora and google’s veo 2 in action: A narrative review of artificial intelligence-driven video generation models transforming healthcare. Cureus 2025, 17, e77593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczar, D.; Sisti, A.; Oliver, J.D.; Helmi, H.; Restrepo, D.J.; Huayllani, M.T.; Spaulding, A.C.; Carter, R.; Rinker, B.D.; Forte, A.J. Artificial intelligent virtual assistant for plastic surgery patient’s frequently asked questions: A pilot study. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 84, e16–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, F.R.; Boczar, D.; Spaulding, A.C.; Quest, D.J.; Samanta, A.; Torres-Guzman, R.A.; Maita, K.C.; Garcia, J.P.; Eldaly, A.S.; Forte, A.J. High satisfaction with a virtual assistant for plastic surgery frequently asked questions. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2023, 43, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, S.A.; Sehgal, A.; Leibovich, B.C.; Cole, D.; Forte, A.J. Comparative analysis of artificial intelligence virtual assistant and large language models in post-operative care. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HeyGen. HeyGen—The most innovative AI Video Generator. Available online: https://www.heygen.com/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Genovese, A.; Prabha, S.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Haider, S.A.; Trabilsy, M.; Tao, C.; Aziz, K.T.; Murray, P.M.; Forte, A.J. Artificial intelligence for patient support: Assessing retrieval-augmented generation for answering postoperative rhinoplasty questions. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2025, 45, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, A.; Prabha, S.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Haider, S.A.; Trabilsy, M.; Tao, C.; Forte, A.J. From Data to Decisions: Leveraging Retrieval-Augmented Generation to Balance Citation Bias in Burn Management Literature. Eur. Burn. J. 2025, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.T.; Miller, J.T. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Intl. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2008, 24, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyzy, M.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Bai, L.; Dix, A.; Leigh, S.; Hunt, S. System usability scale benchmarking for digital health apps: Meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e37290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, A.D.; Branson, I.; Hollett, R.C.; Speelman, C.P.; Rogers, S.L. Do realistic avatars make virtual reality better? Examining human-like avatars for VR social interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2024, 2, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.; Yang, S.-W. Likert-Type Scale. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, D.; MacDorman, K.F. Familiar faces rendered strange: Why inconsistent realism drives characters into the uncanny valley. J. Vis. 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, S.J.; Farid, H. AI-synthesized faces are indistinguishable from real faces and more trustworthy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120481119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, M.; MacDorman, K.F.; Kageki, N. The uncanny valley [from the field]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destephe, M.; Brandao, M.; Kishi, T.; Zecca, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Takanishi, A. Walking in the uncanny valley: Importance of the attractiveness on the acceptance of a robot as a working partner. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisa, A.; Chen, X.; Bryan, E.G.; Bylund, C.L.; Alpert, J.M.; Lok, B.; Fisher, C.L.; Thomas, L.; Krieger, J.L. Virtual Health Assistants in Preventive Cancer Care Communication: Systematic Review. JMIR Cancer 2025, 11, e73616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S. Navigating the maze: Deepfakes, cognitive ability, and social media news skepticism. New Media Soc. 2023, 25, 1108–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbis, N.C.; Doležalová, B.; Soraperra, I. Fooled twice: People cannot detect deepfakes but think they can. iScience 2021, 24, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Vu, P.; Duch, R.M.; Chowdhury, A. Deepfake detection with and without content warnings. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 231214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, E.; De Kleijn, R. Conspiracy thinking and social media use are associated with ability to detect deepfakes. Telemat. Inform. 2024, 87, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri, C.Z.; Bacchi, S.; Wong, W.; Baranage, D.; Sivagurunathan, P.D.; Chan, W.O. A pilot survey of patient perspectives on an artificial intelligence-generated presenter in a patient information video about face-down positioning after vitreoretinal surgery. Ophthalmic Res. 2024, 67, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deighan, M.T.; Ayobi, A.; O’Kane, A.A. Social virtual reality as a mental health tool: How people use VRChat to support social connectedness and wellbeing. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.A.; Drain, M.; Gesell, S.B.; Mylod, D.M.; Kaldenberg, D.O.; Hamilton, J. Patient perceptions of quality in discharge instruction. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 59, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, K.A.; Black, E.E.; Leathers, R.; Belin, T.R.; Abrego, M.; Gironda, M.W.; Wong, D.; Shetty, V.; DerMartirosian, C. A qualitative report of patient problems and postoperative instructions. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005, 63, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstman, M.J.; Mills, W.L.; Herman, L.I.; Cai, C.; Shelton, G.; Qdaisat, T.; Berger, D.H.; Naik, A.D. Patient experience with discharge instructions in postdischarge recovery: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, K.; Mastrocola, M.; Smith, T.; Busconi, B. Patients have poor postoperative recall of information provided the day of surgery but report satisfaction with and high use of an e-mailed postoperative digital media package. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2023, 5, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhud, D.D.; Zokaei, S. Ethical issues of artificial intelligence in medicine and healthcare. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, I–V. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P.; Greenwood, N. Understanding the Hawthorne effect. BMJ 2015, 351, h4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerini, I.; Barni, M.; Battiato, S.; Bestagini, P.; Boato, G.; Bonaventura, T.S.; Bruni, V.; Caldelli, R.; De Natale, F.; De Nicola, R. Deepfake media forensics: State of the art and challenges ahead. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, Rende, Italy, 2–5 September 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, H. Mitigating the harms of manipulated media: Confronting deepfakes and digital deception. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, S.A.; Borna, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Pressman, S.M.; Haider, C.R.; Forte, A.J. The algorithmic divide: A systematic review on AI-driven racial disparities in healthcare. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Porter, D.; Rodwell, E. Artificial love: Revolutions in how AI and AR embodied romantic chatbots can move through relationship stages. AoIR Sel. Pap. Internet Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Item | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usability | System Usability Scale (SUS) | 87.67 (out of 100) | 11.71 |

| Engagement | Visually pleasing | 4.47 | 0.57 |

| Absorbed in Interaction | 4.3 | 0.6 | |

| Enjoyable | 4.27 | 0.58 | |

| Worth time | 4.43 | 0.63 | |

| Rewarding | 4.33 | 0.8 | |

| Exciting | 4.3 | 0.65 | |

| Time slipped away | 3.77 | 1.14 | |

| Acceptability & Trust | Information made sense | 4.6 | 0.56 |

| Perceived as true | 4.67 | 0.8 | |

| From trusted source | 4.5 | 0.57 | |

| Trustworthy | 4.6 | 0.5 | |

| Will improve patient understanding | 4.43 | 0.73 | |

| Effective for education | 4.47 | 0.68 | |

| Would recommend to patients | 4.6 | 0.56 | |

| Believable information | 4.7 | 0.47 | |

| Overall Satisfaction | 4.53 | 0.68 | |

| Avatar matched past knowledge | 3.9 | 1.21 | |

| Eeriness | Eerie, Strange, Unsettling | 1.53 | 0.63 |

| Uncomfortable | 1.4 | 0.5 | |

| Mouth didn’t match | 1.57 | 0.73 | |

| Mouth moved strange | 1.63 | 0.81 | |

| Face Distorted, Uneven | 1.73 | 0.91 | |

| Realism | Face looked stable | 3.3 | 1.37 |

| Face looked clear | 4.53 | 0.82 | |

| Movement Stable | 3.93 | 1.01 | |

| Sound quality | 4.73 | 0.52 | |

| Voice sounded natural | 4.37 | 1.13 | |

| Voice match with physician | 3.83 | 1.42 | |

| To what extent did this agent seem like physician? | 4.2 | 0.66 | |

| Hard to tell if avatar was human or AI | 2.7 | 1.12 | |

| I would believe this was a real person | 3.3 | 1.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haider, S.A.; Prabha, S.; Gomez-Cabello, C.A.; Genovese, A.; Collaco, B.; Wood, N.; Lifson, M.A.; Bagaria, S.; Tao, C.; Forte, A.J. Artificial Intelligence Physician Avatars for Patient Education: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8595. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238595

Haider SA, Prabha S, Gomez-Cabello CA, Genovese A, Collaco B, Wood N, Lifson MA, Bagaria S, Tao C, Forte AJ. Artificial Intelligence Physician Avatars for Patient Education: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8595. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238595

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Syed Ali, Srinivasagam Prabha, Cesar Abraham Gomez-Cabello, Ariana Genovese, Bernardo Collaco, Nadia Wood, Mark A. Lifson, Sanjay Bagaria, Cui Tao, and Antonio Jorge Forte. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence Physician Avatars for Patient Education: A Pilot Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8595. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238595

APA StyleHaider, S. A., Prabha, S., Gomez-Cabello, C. A., Genovese, A., Collaco, B., Wood, N., Lifson, M. A., Bagaria, S., Tao, C., & Forte, A. J. (2025). Artificial Intelligence Physician Avatars for Patient Education: A Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8595. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238595