A Cross-Ethnicity Validated Machine Learning Model for the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals over 50 Years Old

Abstract

1. Introduction

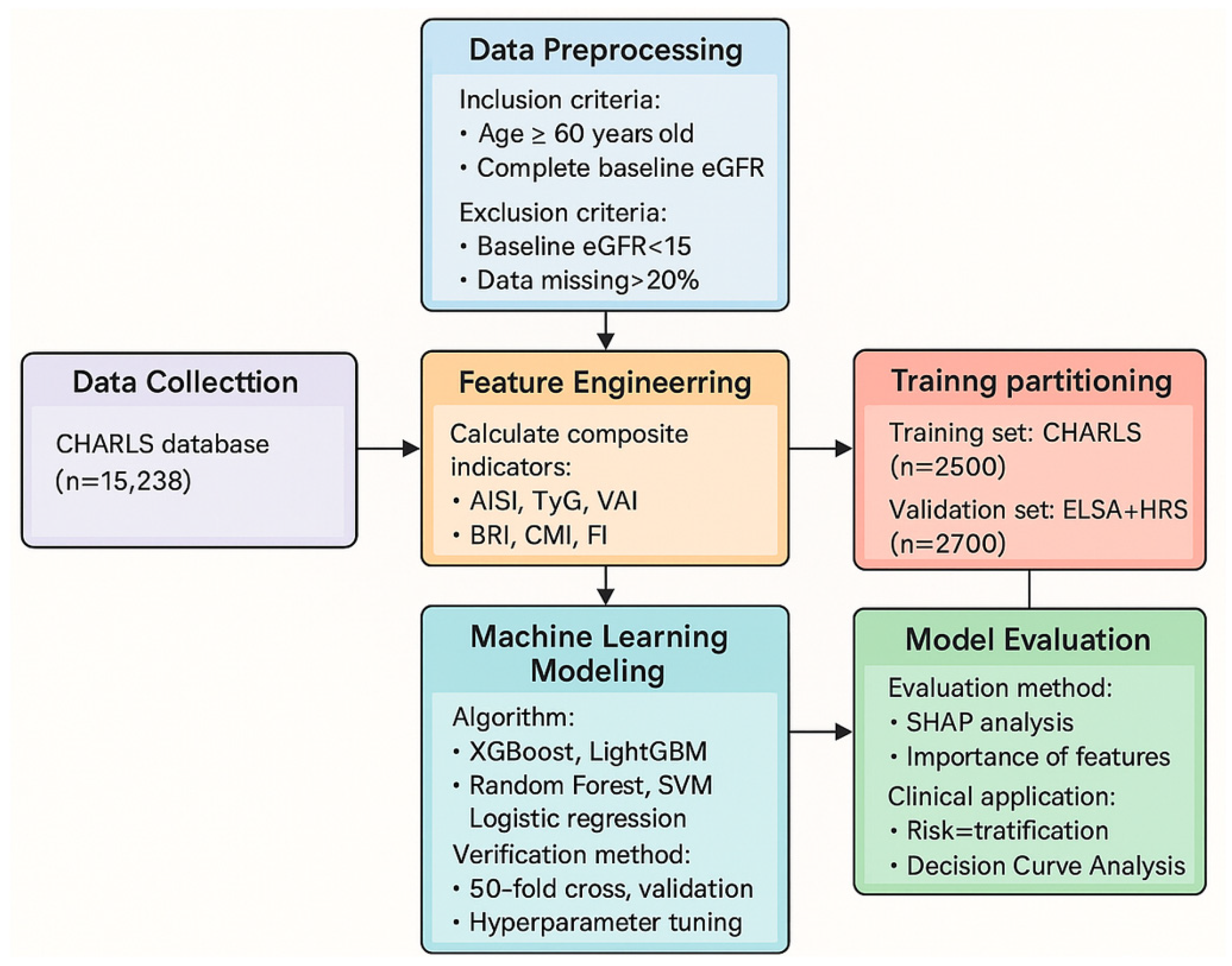

2. Materials and Methods

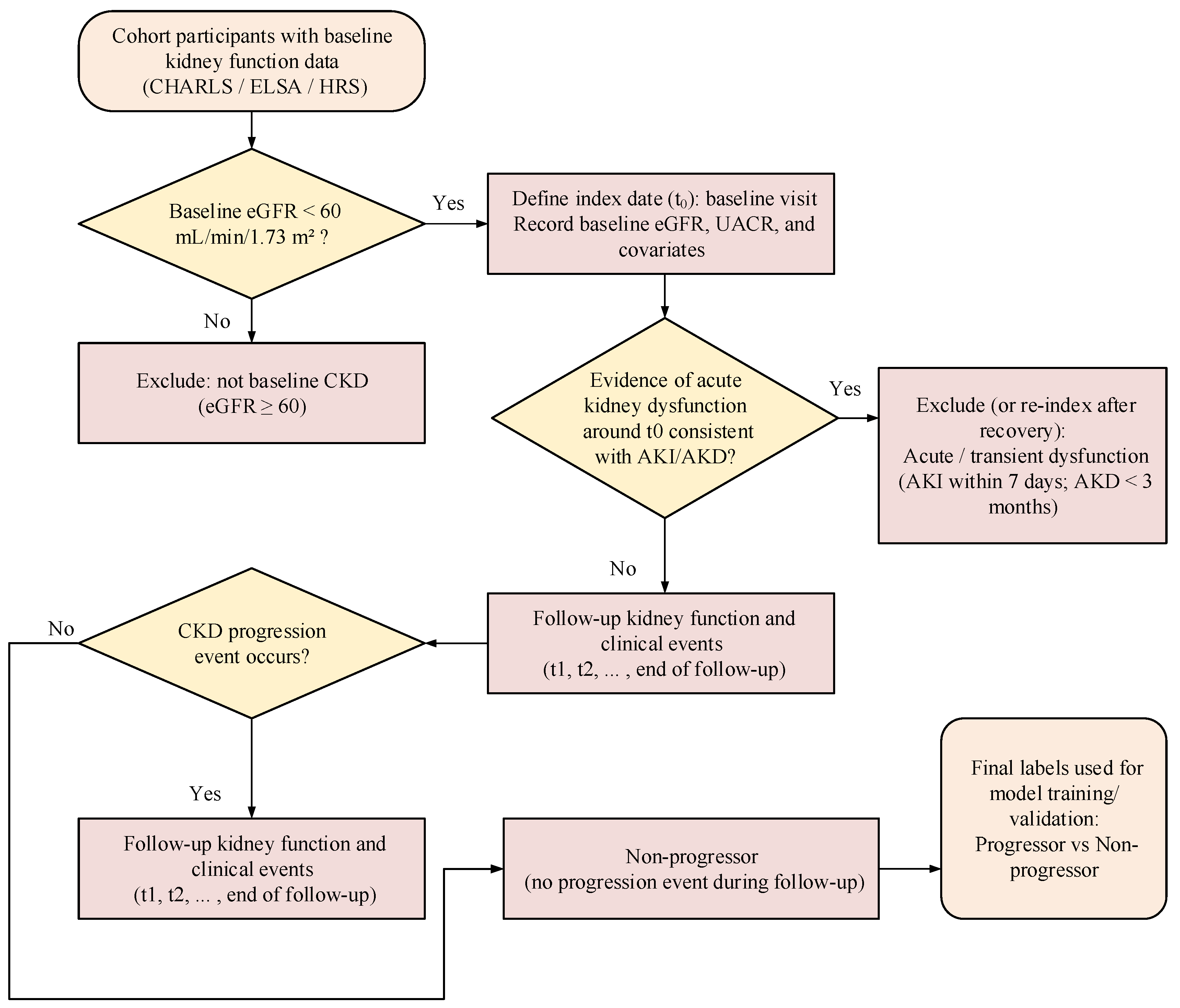

2.1. Data Sources and Preprocessing

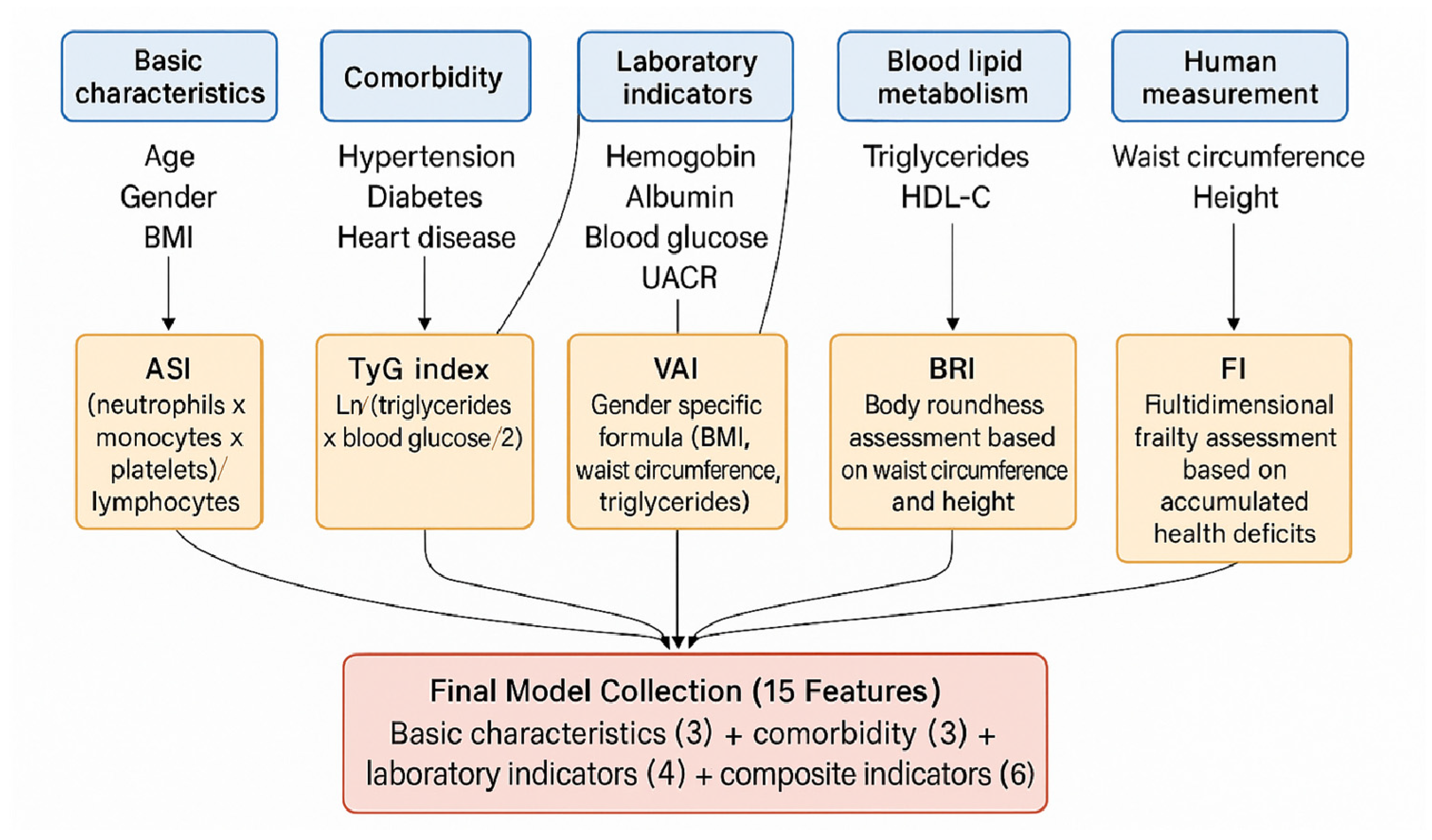

2.2. Feature Engineering and Composite Indicator Calculation

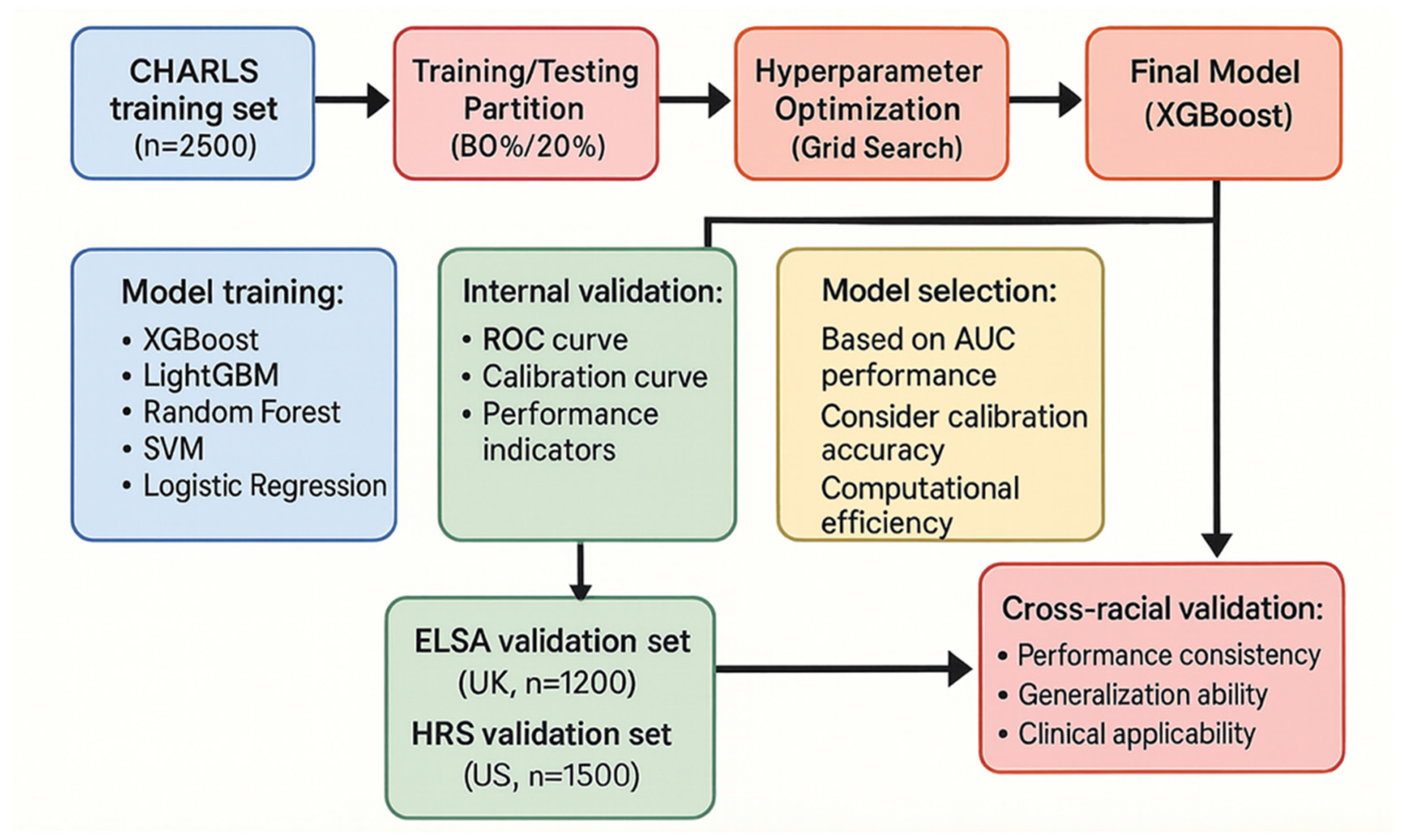

2.3. Model Development and Validation

3. Result

3.1. Study Population Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Analysis of Factors Associated with CKD Progression

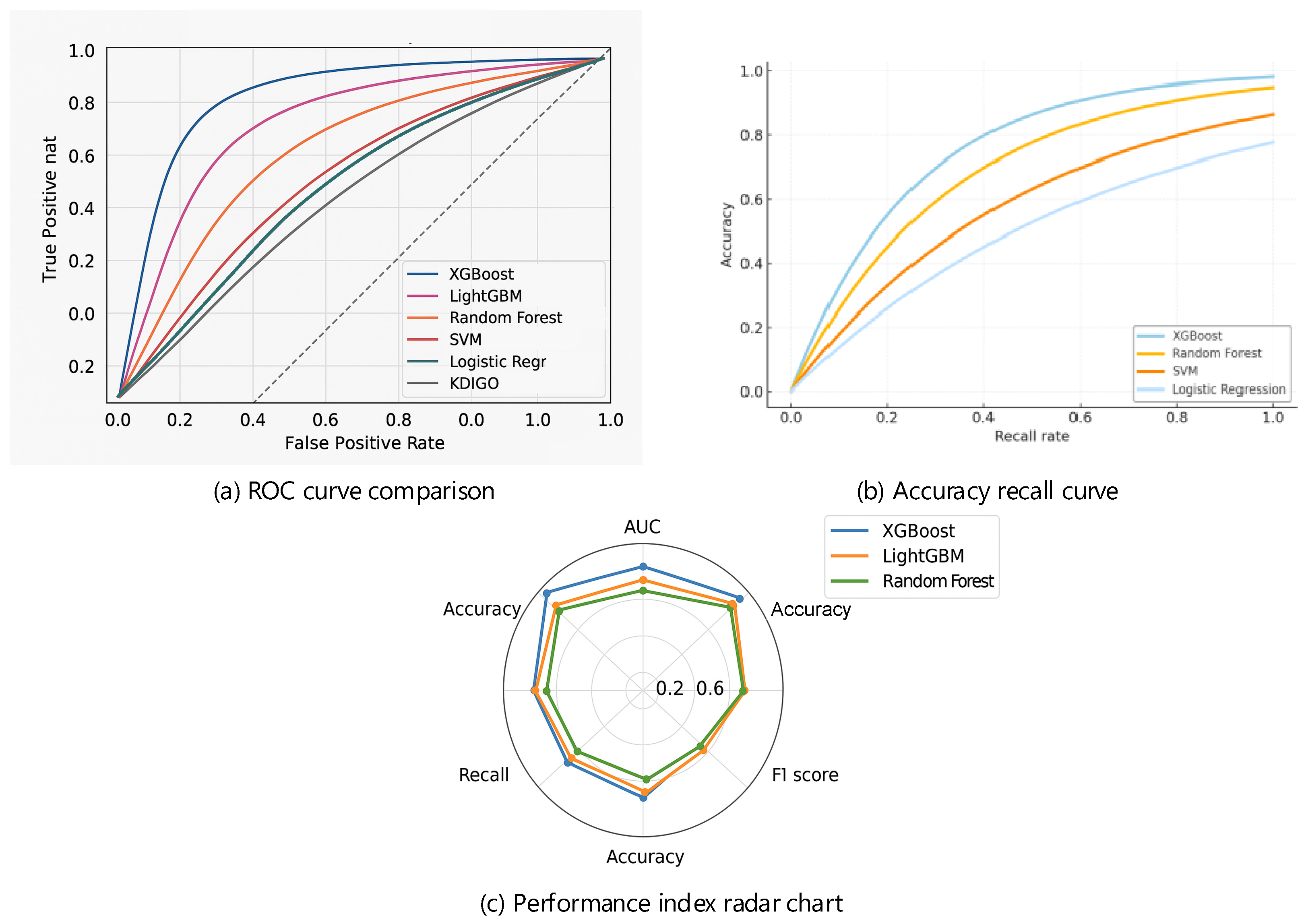

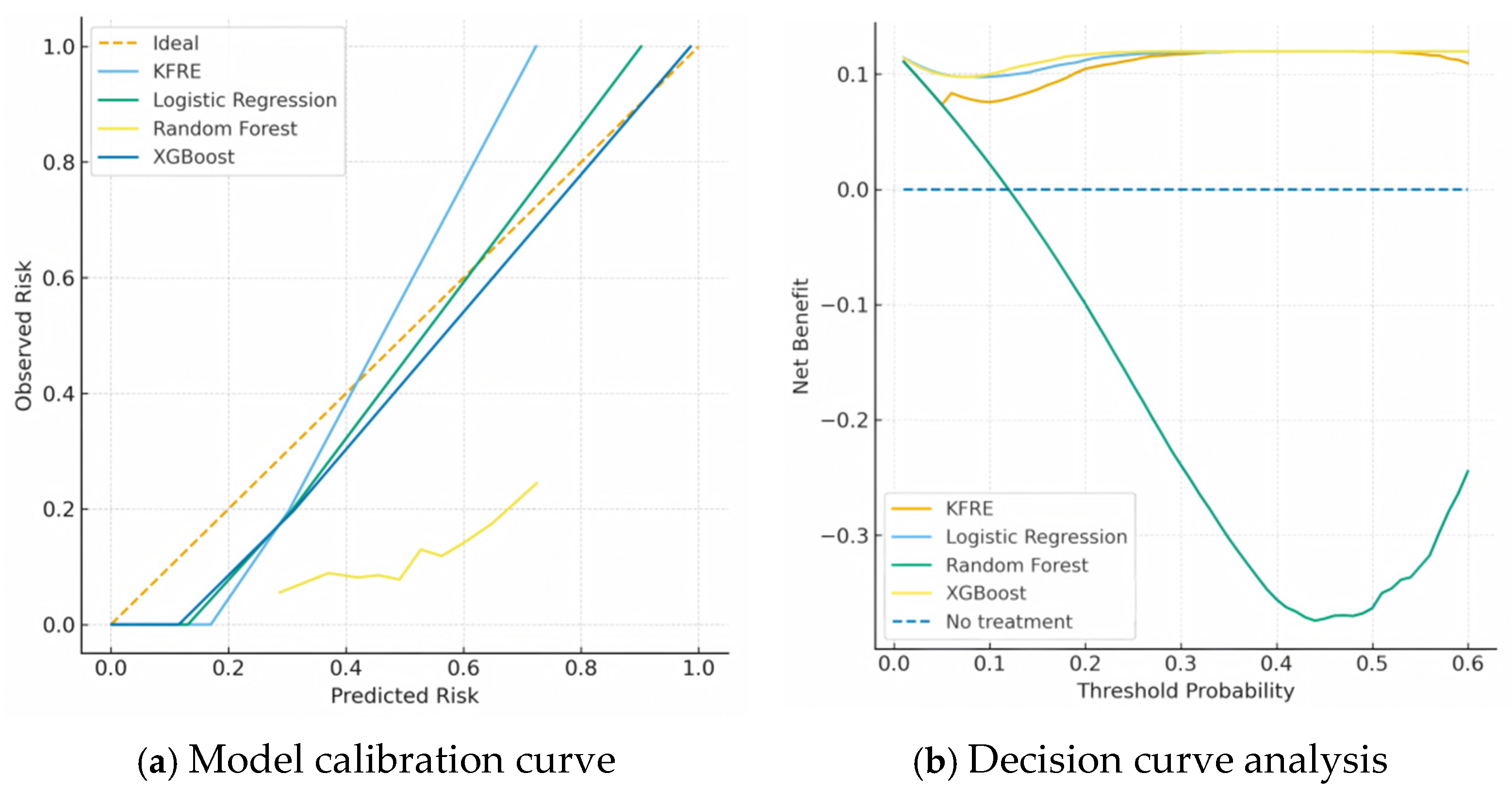

3.3. Machine Learning Model Performance and Comparison

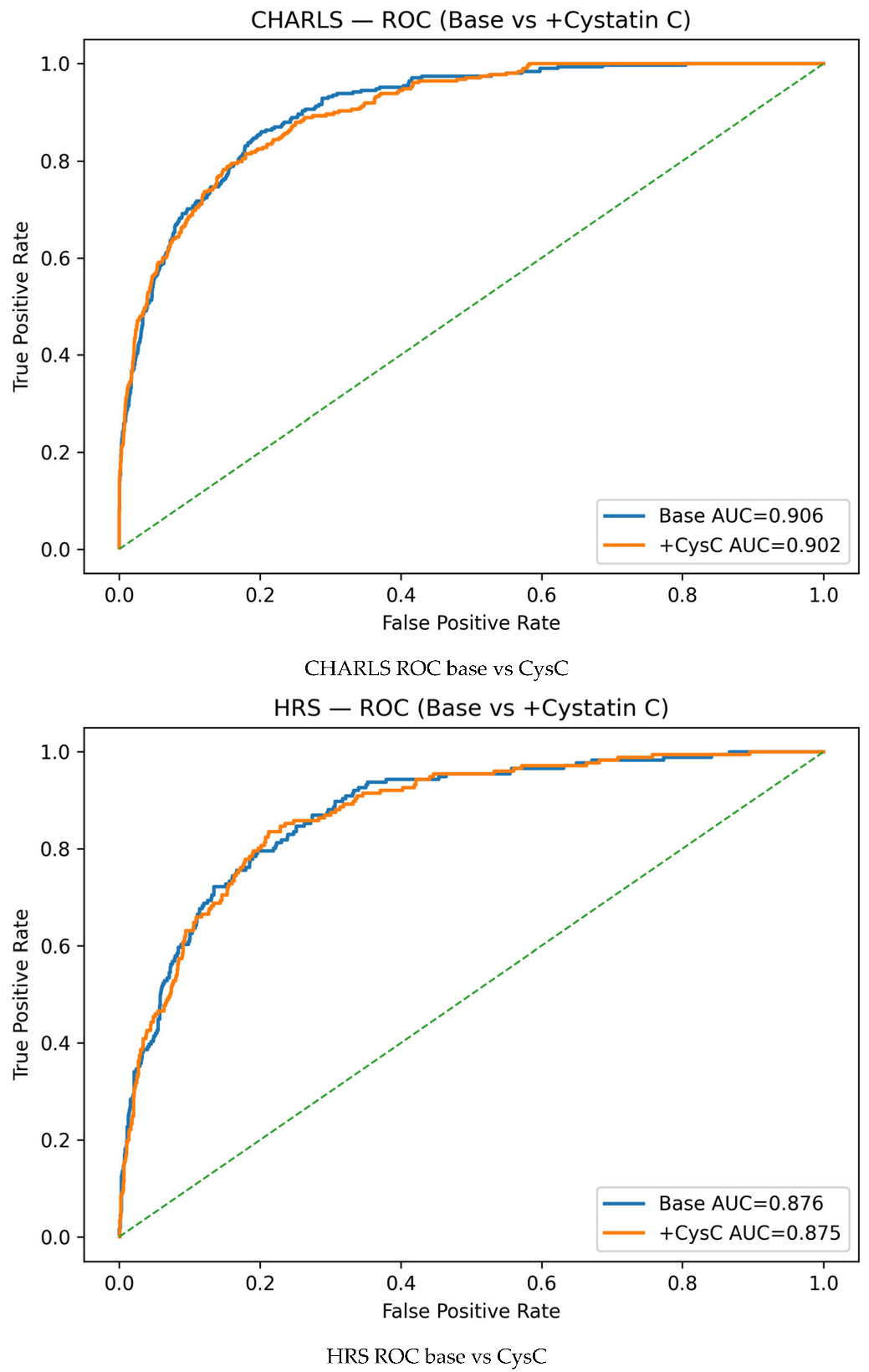

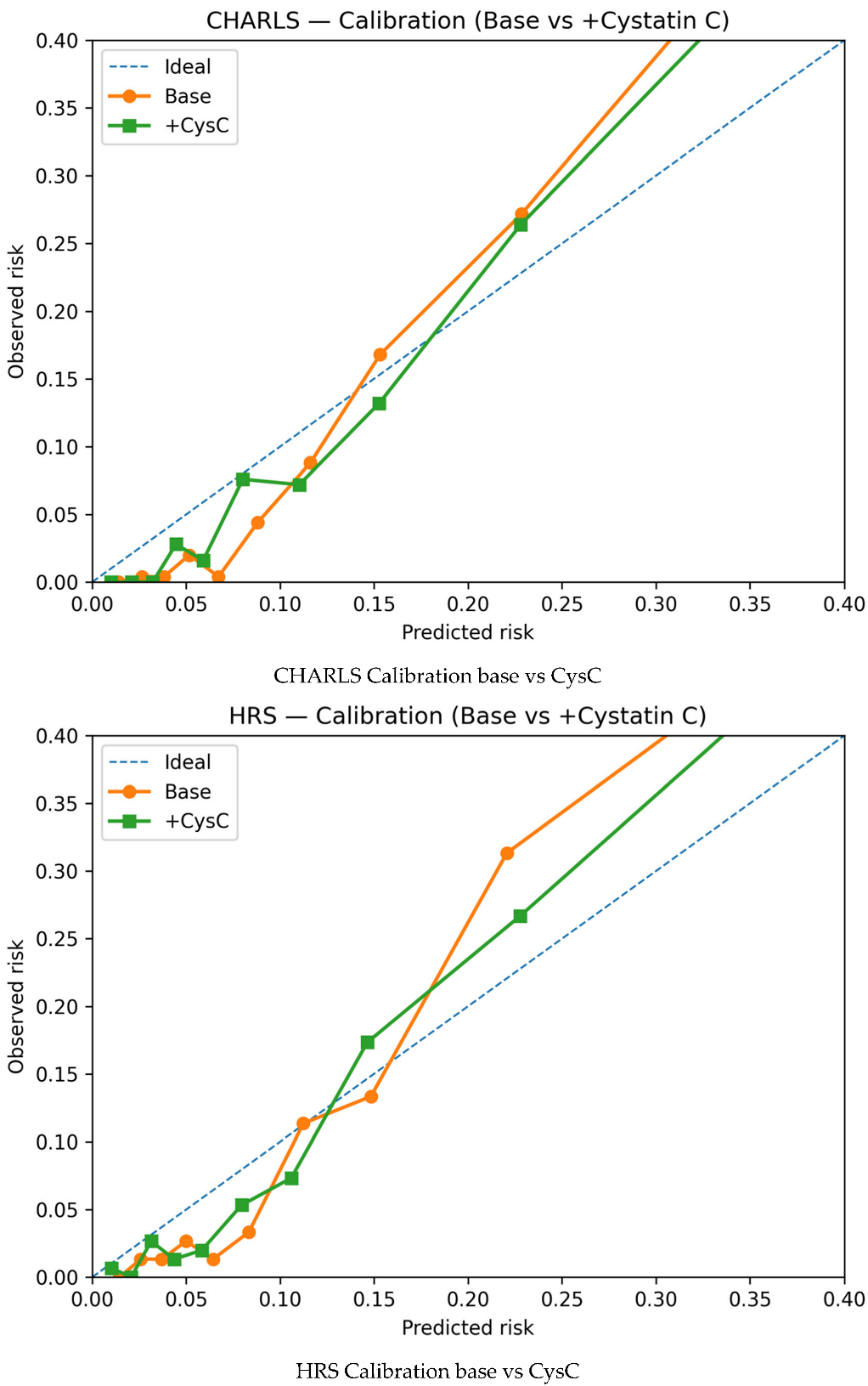

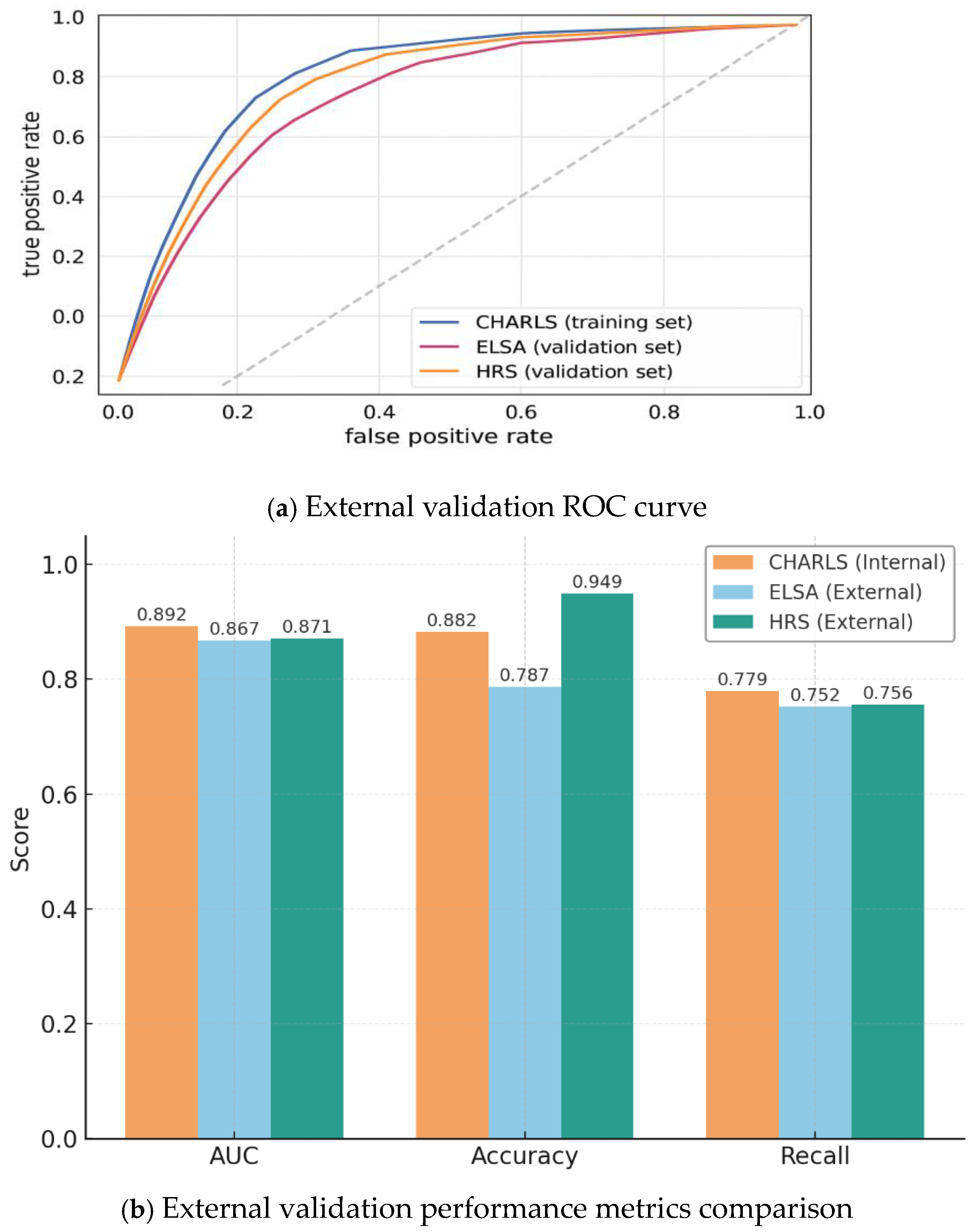

3.4. Model Generalizability: External Validation

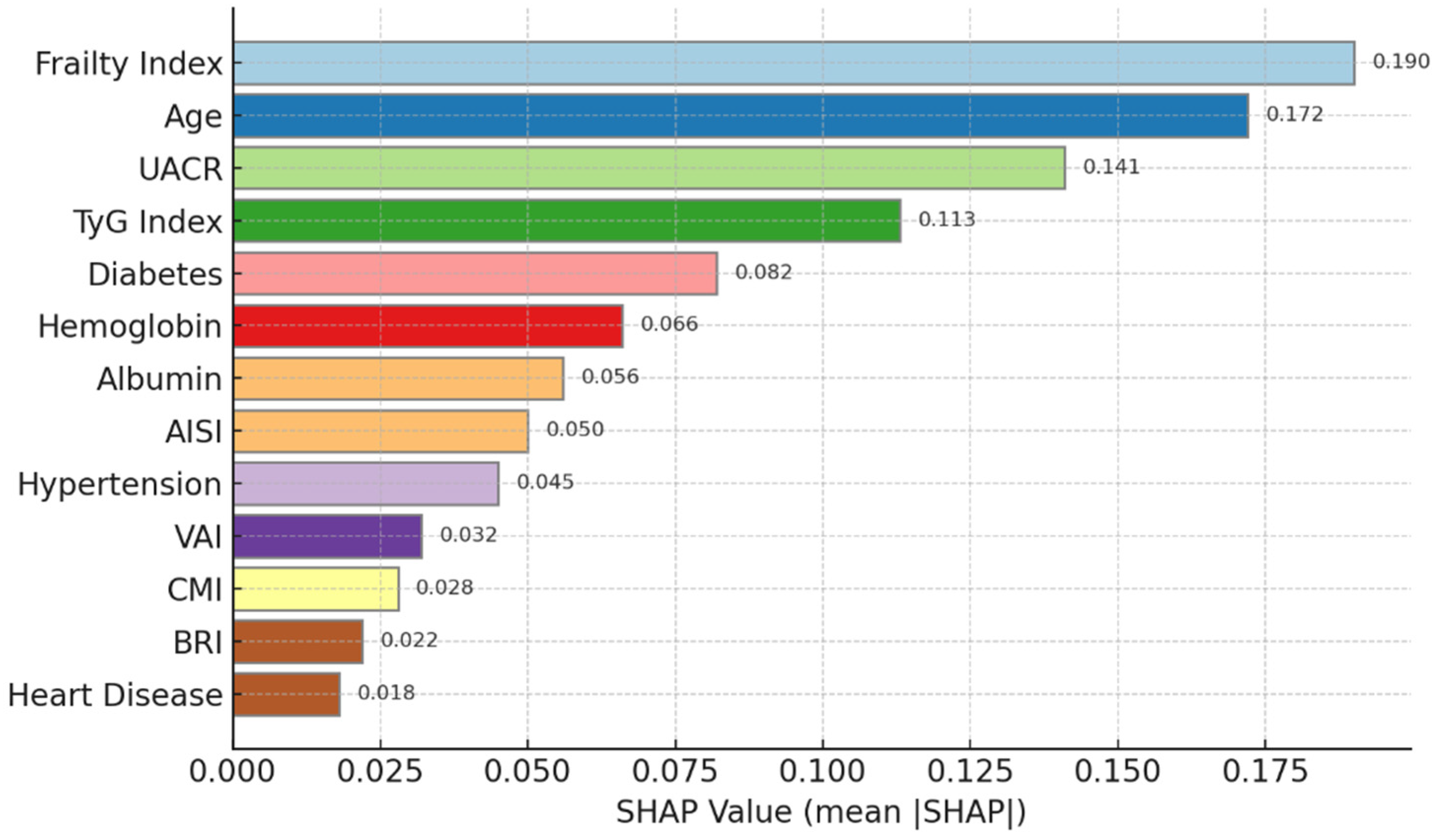

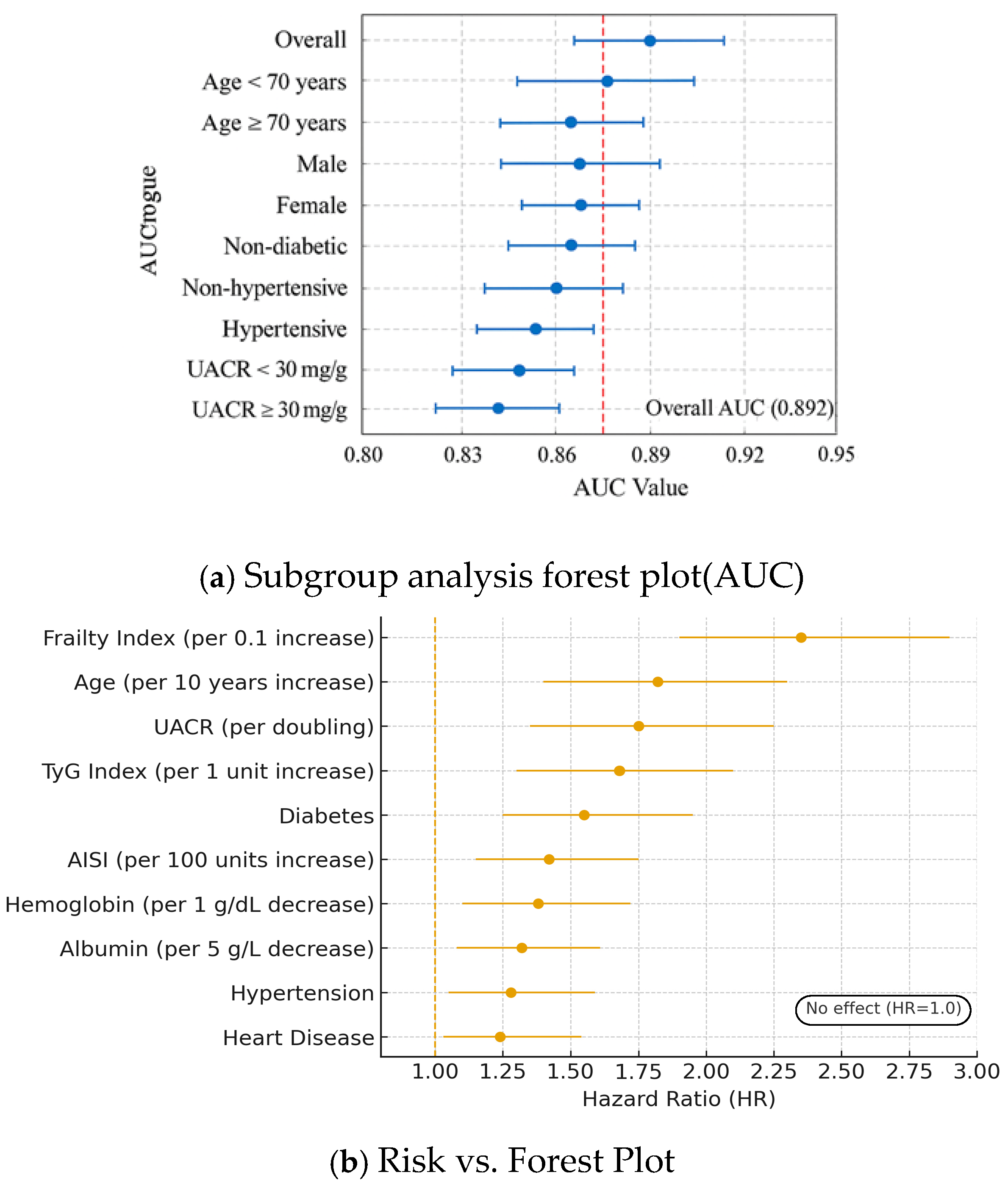

3.5. Subgroup Analysis and Risk Factor Identification

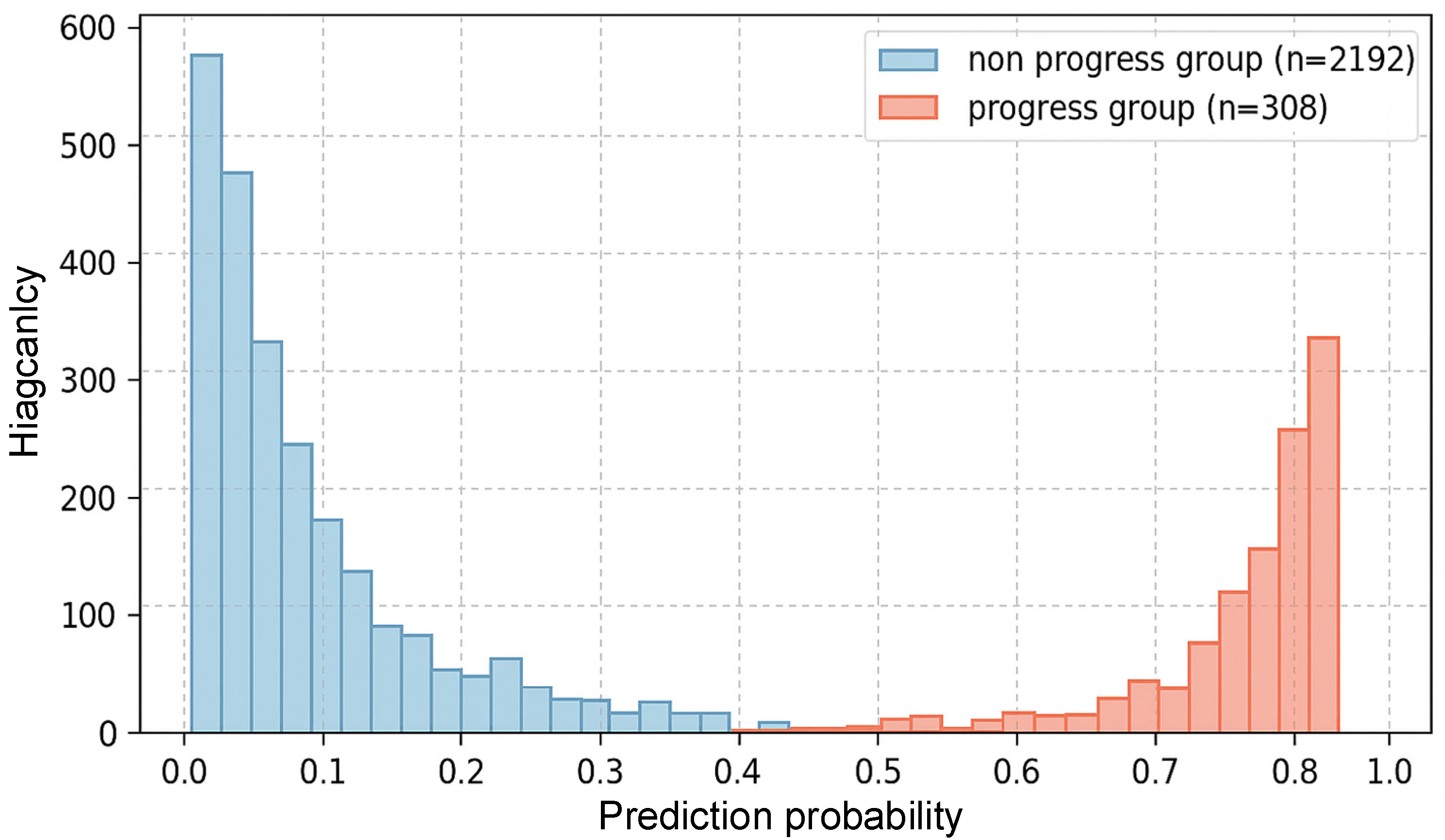

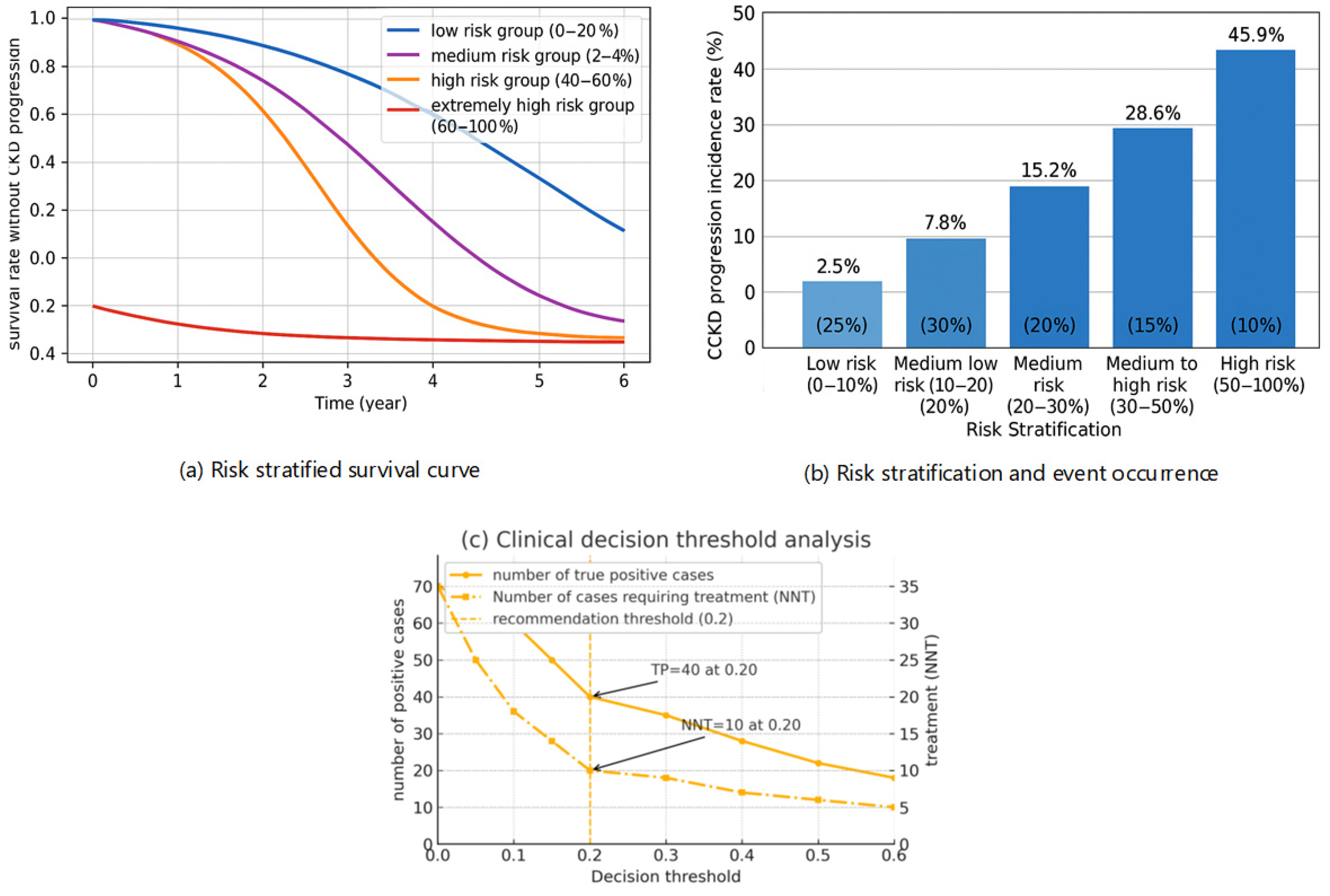

3.6. Clinical Risk Stratification and Utility

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| KFRE | the Kidney Failure Risk Equation |

| CHARLS | the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study |

| ELSA | the English Longitudinal Study of Aging |

| HRS | Health and Retirement Study |

| FI | Frailty index |

| TyG | Triglyceride–glucose |

| AISI | Aggregate index of systemic inflammation |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| KDIGO | the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| CKM | Cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| UACR | Urine albumin-to-creatine ratio |

| BRI | Body Roundness Index; |

| VAI | Visceral Adiposity Index; |

| CMI | Cardiometabolic Index; |

Appendix A

| CKD Risk Calculator (2y/5y)—with North America Recalibration | |||

| Mode: use internal parametric surrogate OR paste your model probability | |||

| Mode | Internal | Choices: Internal/Paste_p (dropdown) | |

| Age (years) | 70 | Numeric | |

| Sex (1 = Male, 0 = Female) | 1 | 0 or 1 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 45 | Numeric | |

| UACR (mg/g) | 100 | Numeric mg/g | |

| Diabetes (1/0) | 0 | Optional | |

| Hypertension (1/0) | 1 | Optional | |

| North America intercept shift (logit)—2y | 0 | Set per site calibration | |

| North America intercept shift (logit)—5y | 0 | Set per site calibration | |

| (Optional) Paste base p_model_2y (0–1) | Used only when Mode = Paste_p | ||

| (Optional) Paste base p_model_5y (0–1) | Used only when Mode = Paste_p | ||

| Transforms | |||

| x_age = (Age-65)/10 | 0.5 | ||

| x_egfr = (60—eGFR)/10 | 1.5 | ||

| x_lnacr = LN(UACR + 1) | 4.615120517 | ||

| Base probabilities (before NA intercept shift) | Recalibrated probabilities (North America shift) | ||

| base_p_2y | 19.166% | p_NA_2y | 19.166% |

| base_p_5y | 40.686% | p_NA_5y | 40.686% |

| Subgroup hints | |||

| UACR category | A2 (30–300) | ||

| G-stage by eGFR | G3a (45–59) | ||

| Notes: (1) If Mode = Paste_p, outputs depend ONLY on cells B12/B13 (base p_model). Inputs above won’t change the risk. (2) To make inputs drive results, set Mode = Internal. (3) North America recalibration uses logit shift (B12 for 2y, B13 for 5y). Default 0.00. (4) Ensure Excel calculation is set to Automatic (Formulas -> Calculation Options -> Automatic). (5) Coefficients can be edited in the ‘Coefficients’ sheet. | |||

Appendix B

| Scenario | Cohort | Horizon | N | Events | Event_Rate | AUC | Brier | Calib_Intercept | Calib_Slope |

| main | CHARLS | 2y | 2500 | 132 | 0.053 | 0.868 | 0.049 | 0.191 | 0.034 |

| main | CHARLS | 5y | 2500 | 312 | 0.125 | 0.891 | 0.075 | 0.346 | 0.069 |

| main | ELSA | 2y | 1200 | 50 | 0.042 | 0.853 | 0.037 | 0.174 | 0.031 |

| main | ELSA | 5y | 1200 | 104 | 0.087 | 0.867 | 0.062 | 0.273 | 0.053 |

| main | HRS | 2y | 1500 | 83 | 0.055 | 0.835 | 0.054 | 0.189 | 0.032 |

| main | HRS | 5y | 1500 | 189 | 0.126 | 0.867 | 0.082 | 0.354 | 0.07 |

| S2_exclude_any_AKI | CHARLS | 2y | 2315 | 120 | 0.052 | 0.867 | 0.048 | 0.188 | 0.034 |

| S2_exclude_any_AKI | CHARLS | 5y | 2315 | 290 | 0.125 | 0.891 | 0.075 | 0.349 | 0.07 |

| S2_exclude_any_AKI | ELSA | 2y | 1084 | 45 | 0.042 | 0.851 | 0.037 | 0.173 | 0.03 |

| S2_exclude_any_AKI | ELSA | 5y | 1084 | 95 | 0.088 | 0.878 | 0.061 | 0.282 | 0.055 |

| S2_exclude_any_AKI | HRS | 2y | 1364 | 82 | 0.06 | 0.837 | 0.056 | 0.206 | 0.035 |

| S2_exclude_any_AKI | HRS | 5y | 1364 | 177 | 0.13 | 0.868 | 0.083 | 0.364 | 0.072 |

Appendix C

References

- Romagnani, P.; Agarwal, R.; Chan, J.C.N.; Levin, A.; Kalyesubula, R.; Karam, S.; Nangaku, M.; Rodríguez-Iturbe, B.; Anders, H.-J. Chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesnaye, N.C.; Ortiz, A.; Zoccali, C.; Stel, V.S.; Jager, K.J. The impact of population ageing on the burden of chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Guo, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yu, X.; Shuai, P. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease and its underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, Q.; Stafford, L.K.; Vos, T.; Thomé, F.S.; Aalruz, H.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abedi, A.; Abiodun, O.O.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of kidney failure with replacement therapy and associated aetiologies, 1990–2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e1378–e1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.-T.; Chao, C.-T.; Lin, S.-H. Chronic Kidney Disease: Strategies to Retard Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.-Q.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Zheng, K.I.; Rios, R.S.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Yuan, W.-J.; Zheng, M.-H. MAFLD and risk of CKD. Metabolism 2021, 115, 4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Chow, S.L.; Mathew, R.O.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Després, J.-P.; et al. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1636–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangri, N. A Predictive Model for Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease to Kidney Failure. JAMA 2011, 305, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramspek, C.L.; de Jong, Y.; Dekker, F.W.; van Diepen, M. Towards the best kidney failure prediction tool: A systematic review and selection aid. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2020, 35, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangri, N.; Grams, M.E.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Appel, L.J.; Astor, B.C.; Chodick, G.; Collins, A.J.; Djurdjev, O.; Elley, C.R.; et al. Multinational Assessment of Accuracy of Equations for Predicting Risk of Kidney Failure: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 315, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, E.B.; Yang, X.; Thorp, M.L.; Arnold, B.M.; Tabano, D.C.; Petrik, A.F.; Smith, D.H.; Platt, R.W.; Johnson, E.S. Predicting 5-Year Risk of RRT in Stage 3 or 4 CKD: Development and External Validation. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2016, 12, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, A.; Fluck, N.; Prescott, G.J.; Robertson, L.; Simpson, W.G.; Cairns Smith, W.; Black, C. Looking to the future: Predicting renal replacement outcomes in a large community cohort with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Guo, L.; Xu, F. Artificial intelligence in nephrology: Predicting CKD progression and personalizing treatment. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Tong, M. Artificial intelligence in predicting chronic kidney disease prognosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2435483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mridha, K.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. Building Trust in Clinical AI: A Web-Based Explainable Decision Support System for Chronic Kidney Disease. AMIA Jt. Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2025, 2025, 375–384. [Google Scholar]

- ElShawi, R.; Sherif, Y.; Al-Mallah, M.; Sakr, S. Interpretability in healthcare: A comparative study of local machine learning interpretability techniques. Comput. Intell. 2020, 37, 1633–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoers, N.; Antignac, C.; Bergmann, C.; Dahan, K.; Giglio, S.; Heidet, L.; Lipska-Ziętkiewicz, B.S.; Noris, M.; Remuzzi, G.; Vargas-Poussou, R.; et al. Genetic testing in the diagnosis of chronic kidney disease: Recommendations for clinical practice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2022, 37, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batte, A.; Shahrin, L.; Claure-Del Granado, R.; Luyckx, V.A.; Conroy, A.L. Infections and Acute Kidney Injury: A Global Perspective. Semin. Nephrol. 2023, 43, 151466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Brenner, B.M. Birth weight, malnutrition and kidney-associated outcomes—A global concern. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2015, 11, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Tuttle, K.R.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Gharbi, M.B.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Johnson, D.W.; Liu, Z.-H.; Massy, Z.A.; Moe, O.; Nelson, R.G.; et al. Reducing major risk factors for chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2017, 7, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Wu, J.; Kane, A.E.; Howlett, S.E. The intersection of frailty and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 893–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.J.; Miksza, J.; Zaccardi, F.; Lawson, C.; Nixon, A.C.; Young, H.M.L.; Khunti, K.; Smith, A.C. Associations between frailty trajectories and cardiovascular, renal, and mortality outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2426–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.C.-K.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Ng, J.K.-C.; Tian, N.; Burns, A.; Chow, K.-M.; Szeto, C.-C.; Li, P.K.-T. Frailty in patients on dialysis. Kidney Int. 2024, 106, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, B.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, L. Frailty, genetic predisposition, and incident chronic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, C.-T.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Merchant, R.A. Sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and frailty in individuals with chronic kidney disease: A comprehensive review. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Cheng, C.; Liang, T.; Tang, L.; Guo, X.; Liu, X. Development and multi-cohort validation of a machine learning-based simplified frailty assessment tool for clinical risk prediction. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lin, Z.; Tang, Z.; Feng, L.; Lei, N.; Chen, H.; Chen, G.; Tan, Q. Chronic kidney Disease overall survival prediction model based on frailty index score: Construction and validation using NHANES data. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2476740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, U.; Bashyal, B.; Shrestha, A.; Koirala, B.; Sharma, S.K. Frailty and chronic diseases: A bi-directional relationship. Aging Med. 2024, 7, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-T.; Lin, S.-H. Uremic Toxins and Frailty in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Molecular Insight. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, R.A.; Vathsala, A. Healthy aging and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 41, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, S.; Chi, C.; Fan, X.; Tang, J.; Ji, H.; Teliewubai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. Association between macro- and microvascular damage and the triglyceride glucose index in community-dwelling elderly individuals: The Northern Shanghai Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2019, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, K.; Bao, D.; Huang, Z.; Gu, W.; Chen, K. Associations of insulin resistance surrogate with resistant hypertension and the severity of hypertension in the chronic kidney disease population. J. Hypertens. 2025, 43, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.; Yuan, X.; Peng, M.; Shi, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, F.; Song, K.; Xu, G.; Shi, J. The role of insulin resistance in the longitudinal progression from NAFLD to cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, W.; Hao, Y.-H.; Wan, M.-G.; Zhang, J.-L.; Huang, H.-M.; Song, C.-Z.; He, Q.-J.; Fan, N.-Y.; Yao, X.; Chen, C.-Y. Comparative study of triglyceride glucose index and coronary heart disease risk in middle aged and elderly Chinese and British populations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soraneh, S.; Ebrahimi, N.; Masrouri, S.; Tohidi, M.; Azizi, F.; Hadaegh, F. Association of the triglyceride-glucose index and its combination with obesity indices with cardio-renal-metabolic multimorbidity: Two decades of follow-up in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Gao, S.; Zhao, R.; Shen, P.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Duan, C.; Wang, Y.; Ni, H.; Zhou, L.; et al. Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Chen, S.; Xia, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wu, S.; Wang, A. Pathways from insulin resistance to incident cardiovascular disease: A Bayesian network analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizo, S.; Martínez-Arias, L.; Alonso-Montes, C.; Cannata, P.; Martín-Carro, B.; Fernández-Martín, J.L.; Naves-Díaz, M.; Carrillo-López, N.; Cannata-Andía, J.B. Fibrosis in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathogenesis and Consequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Lamas, S.; Ortiz, A.; Rodrigues-Diez, R.R. Targeting the progression of chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Jiao, B. The Interplay between Immune and Metabolic Pathways in Kidney Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, V.; Shaw, I.W.; Kramann, R. Metabolism at the crossroads of inflammation and fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 21, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanriover, C.; Copur, S.; Mutlu, A.; Peltek, I.B.; Galassi, A.; Ciceri, P.; Cozzolino, M.; Kanbay, M. Early aging and premature vascular aging in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2023, 16, 1751–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garavaglia, M.L.; Giustarini, D.; Colombo, G.; Reggiani, F.; Finazzi, S.; Calatroni, M.; Landoni, L.; Portinaro, N.M.; Milzani, A.; Badalamenti, S.; et al. Blood Thiol Redox State in Chronic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Du, D. Aging and chronic kidney disease: Epidemiology, therapy, management and the role of immunity. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 17, sfae235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | CHARLS Training Set (n = 2500) | ELSA Validation Set (n = 1200) | HRS Validation Set (n = 1500) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 68.3 ± 6.2 | 72.1 ± 7.8 | 70.5 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1285 (51.4) | 572 (47.7) | 712 (47.5) | 0.023 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 3.5 | 26.8 ± 4.2 | 27.3 ± 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 1325 (53.0) | 642 (53.5) | 825 (55.0) | 0.421 |

| Diabetes | 625 (25.0) | 312 (26.0) | 420 (28.0) | 0.089 |

| Heart Disease | 500 (20.0) | 252 (21.0) | 330 (22.0) | 0.267 |

| Laboratory Parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 ± 1.6 | 13.2 ± 1.5 | 13.4 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.5 ± 4.2 | 39.2 ± 4.0 | 39.8 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 45.2 [15.8–125.6] | 38.7 [12.3–98.4] | 42.1 [14.2–110.3] | 0.003 |

| Composite Indicators | ||||

| AISI | 325.6 [156.8–685.4] | 298.3 [142.5–624.1] | 312.8 [148.9–657.2] | 0.015 |

| TyG index | 8.65 ± 0.72 | 8.52 ± 0.68 | 8.59 ± 0.71 | <0.001 |

| BRI | 4.12 ± 1.25 | 4.85 ± 1.42 | 4.92 ± 1.38 | <0.001 |

| VAI | 2.38 ± 1.06 | 2.65 ± 1.12 | 2.71 ± 1.15 | <0.001 |

| CMI | 1.25 ± 0.58 | 1.32 ± 0.61 | 1.35 ± 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Frailty index (FI) | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Study Outcomes | ||||

| CKD progression, n (%) | 308 (12.3) | 121 (10.1) | 176 (11.7) | 0.142 |

| Characteristic | Non-Progressors (n = 2192) | Progressors (n = 308) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 67.5 ± 6.0 | 73.2 ± 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1125 (51.3) | 160 (51.9) | 0.841 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.4 | 22.8 ± 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 1125 (51.3) | 200 (64.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 500 (22.8) | 125 (40.6) | <0.001 |

| Heart Disease | 408 (18.6) | 92 (29.9) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory Parameters | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.0 ± 1.5 | 11.2 ± 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.1 ± 3.9 | 34.8 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 7.5 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 32.5 [12.8–85.4] | 156.8 [65.2–385.6] | <0.001 |

| Composite Indicators | |||

| AISI | 298.4 [142.6–625.3] | 512.8 [245.6–1085.2] | <0.001 |

| TyG index | 8.55 ± 0.65 | 9.25 ± 0.85 | <0.001 |

| BRI | 4.05 ± 1.18 | 4.65 ± 1.52 | <0.001 |

| VAI | 2.28 ± 0.98 | 3.05 ± 1.25 | <0.001 |

| CMI | 1.18 ± 0.52 | 1.68 ± 0.75 | <0.001 |

| FI | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Predictor | Unit/Contrast | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty index (FI) | per 0.1 increase | 2.35 | 1.95–2.83 | <0.001 |

| Age | per 10-year increase | 1.82 | 1.55–2.14 | <0.001 |

| UACR | per doubling (log2) | 1.75 | 1.48–2.06 | <0.001 |

| TyG index | per 1-unit increase | 1.68 | 1.40–2.01 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | yes vs. no | 1.42 | 1.18–1.71 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | yes vs. no | 1.28 | 1.06–1.55 | 0.010 |

| Albumin | per 5 g/L increase | 0.86 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | per 1 g/dL increase | 0.92 | 0.88–0.97 | 0.002 |

| Model | AUC | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Brier Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.892 | 0.880 | 0.360 | 0.780 | 0.492 | 0.090 |

| LightGBM | 0.885 | 0.875 | 0.340 | 0.760 | 0.468 | 0.094 |

| RF | 0.874 | 0.868 | 0.320 | 0.730 | 0.444 | 0.100 |

| SVM | 0.843 | 0.855 | 0.280 | 0.690 | 0.401 | 0.108 |

| LR | 0.821 | 0.848 | 0.260 | 0.660 | 0.371 | 0.112 |

| KDIGO | 0.745 | 0.810 | 0.210 | 0.580 | 0.308 | 0.135 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, X.; Dou, P.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, P. A Cross-Ethnicity Validated Machine Learning Model for the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals over 50 Years Old. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020825

Wang L, Zhang W, Zhong X, Dou P, Wu Y, Zheng X, Zhang P. A Cross-Ethnicity Validated Machine Learning Model for the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals over 50 Years Old. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):825. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020825

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Langkun, Wei Zhang, Xin Zhong, Peng Dou, Yuwei Wu, Xiaonan Zheng, and Peng Zhang. 2026. "A Cross-Ethnicity Validated Machine Learning Model for the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals over 50 Years Old" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020825

APA StyleWang, L., Zhang, W., Zhong, X., Dou, P., Wu, Y., Zheng, X., & Zhang, P. (2026). A Cross-Ethnicity Validated Machine Learning Model for the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease in Individuals over 50 Years Old. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020825