Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

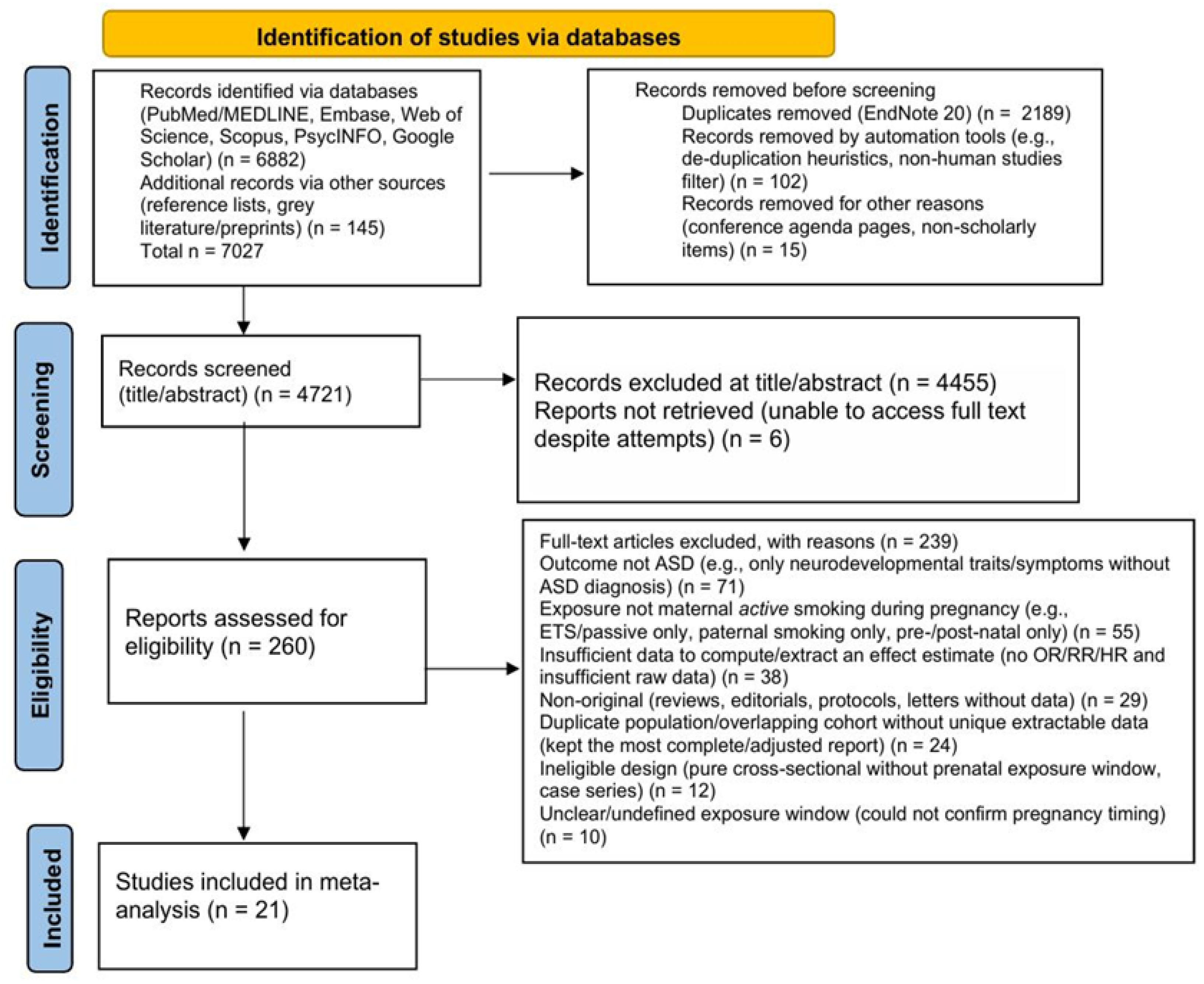

2.3. PRISMA Process

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

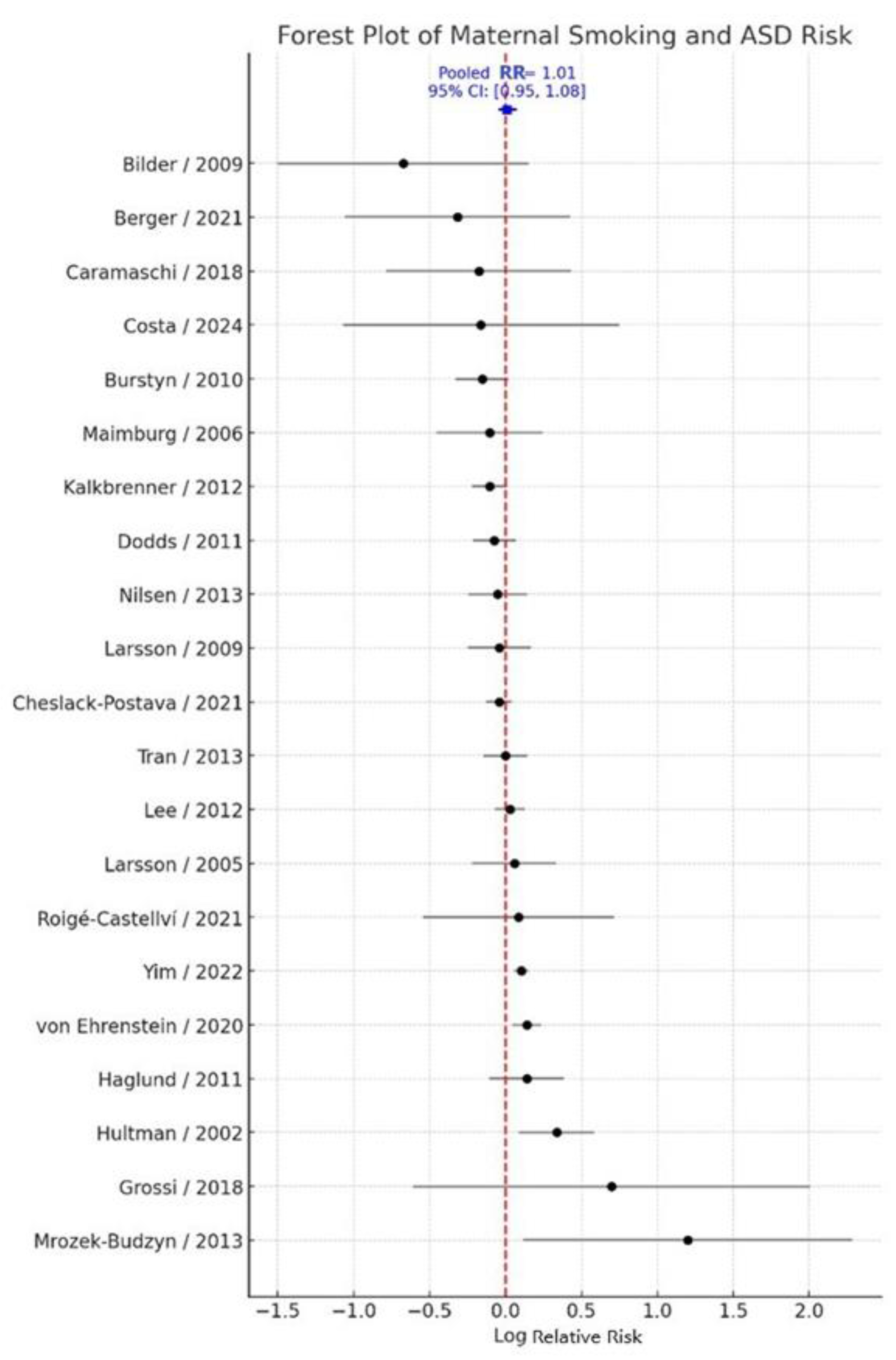

3.1. Primary Meta-Analysis

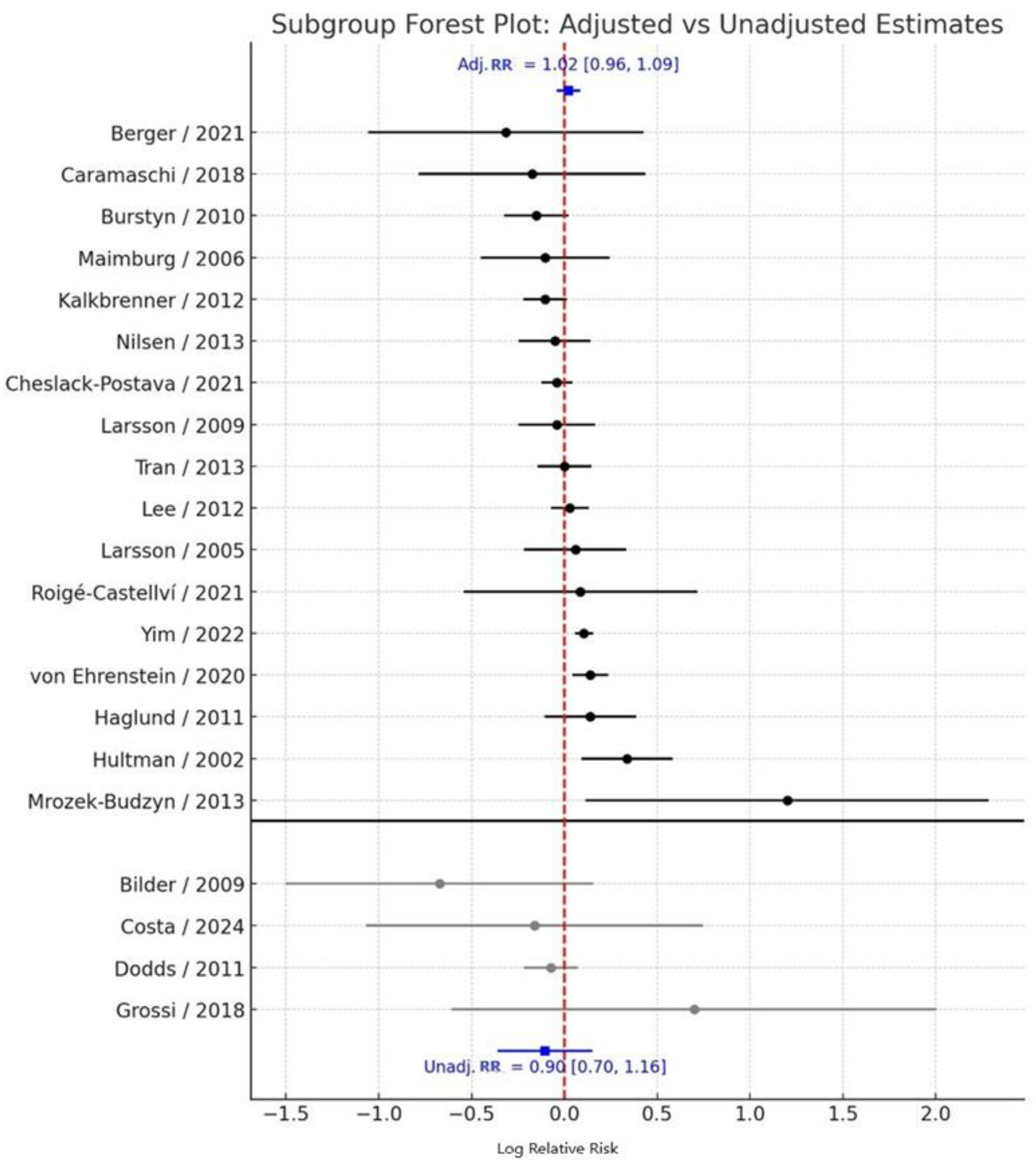

3.2. Adjusted vs. Unadjusted Estimates

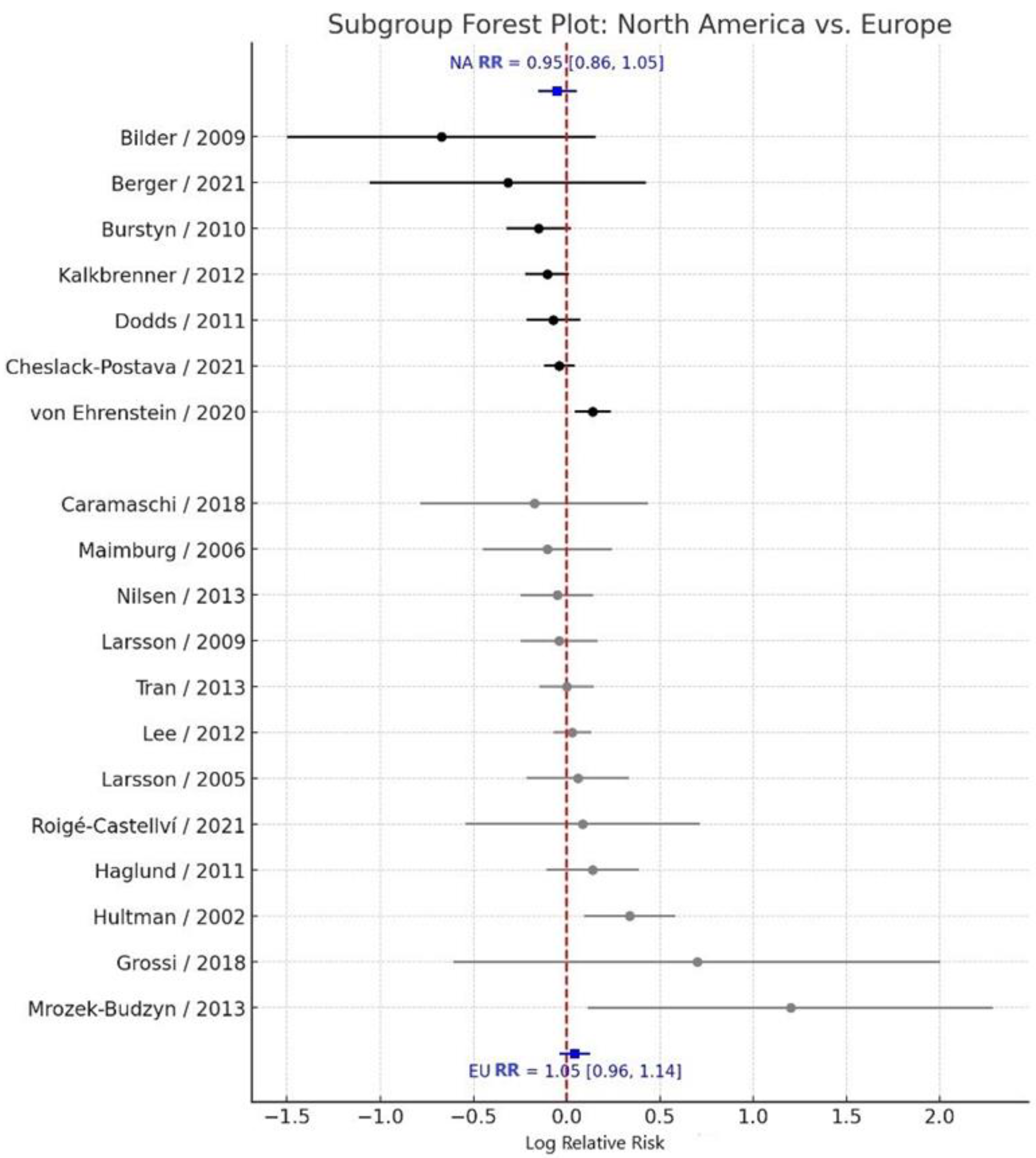

3.3. Subgroup Analysis by Geographic Region

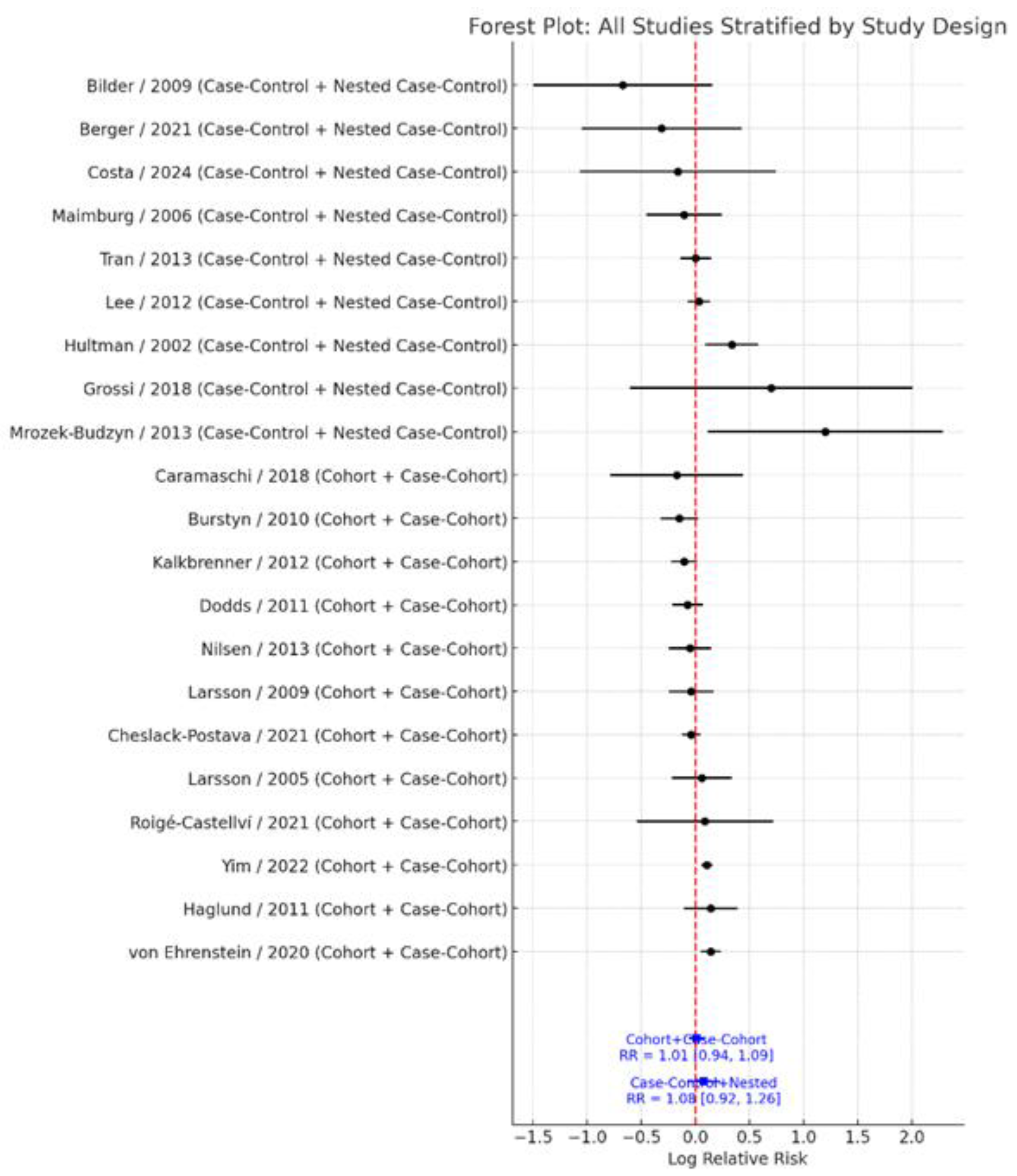

3.4. Subgroup Analysis by Study Design

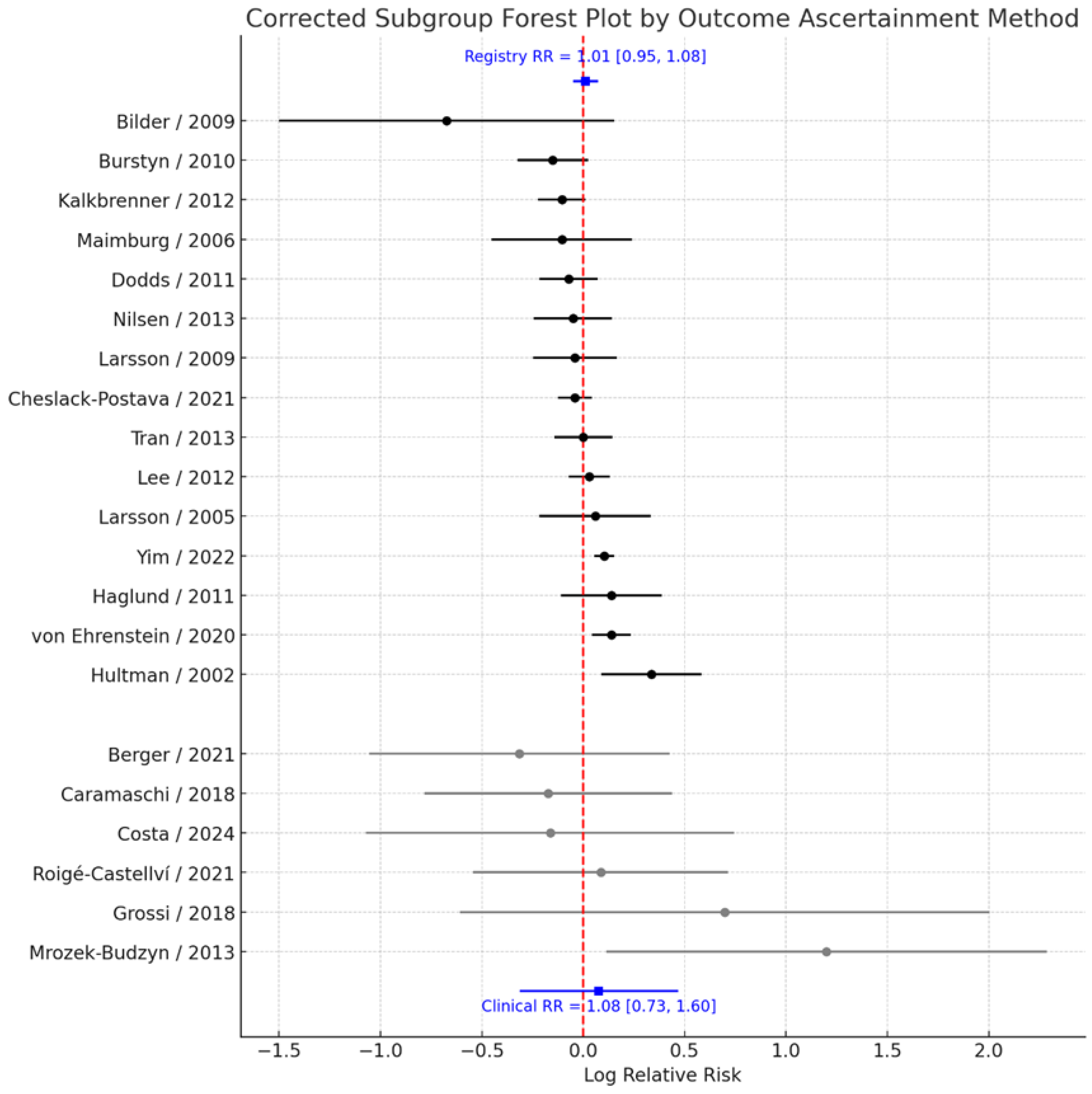

3.5. Subgroup Analysis by Outcome Ascertainment

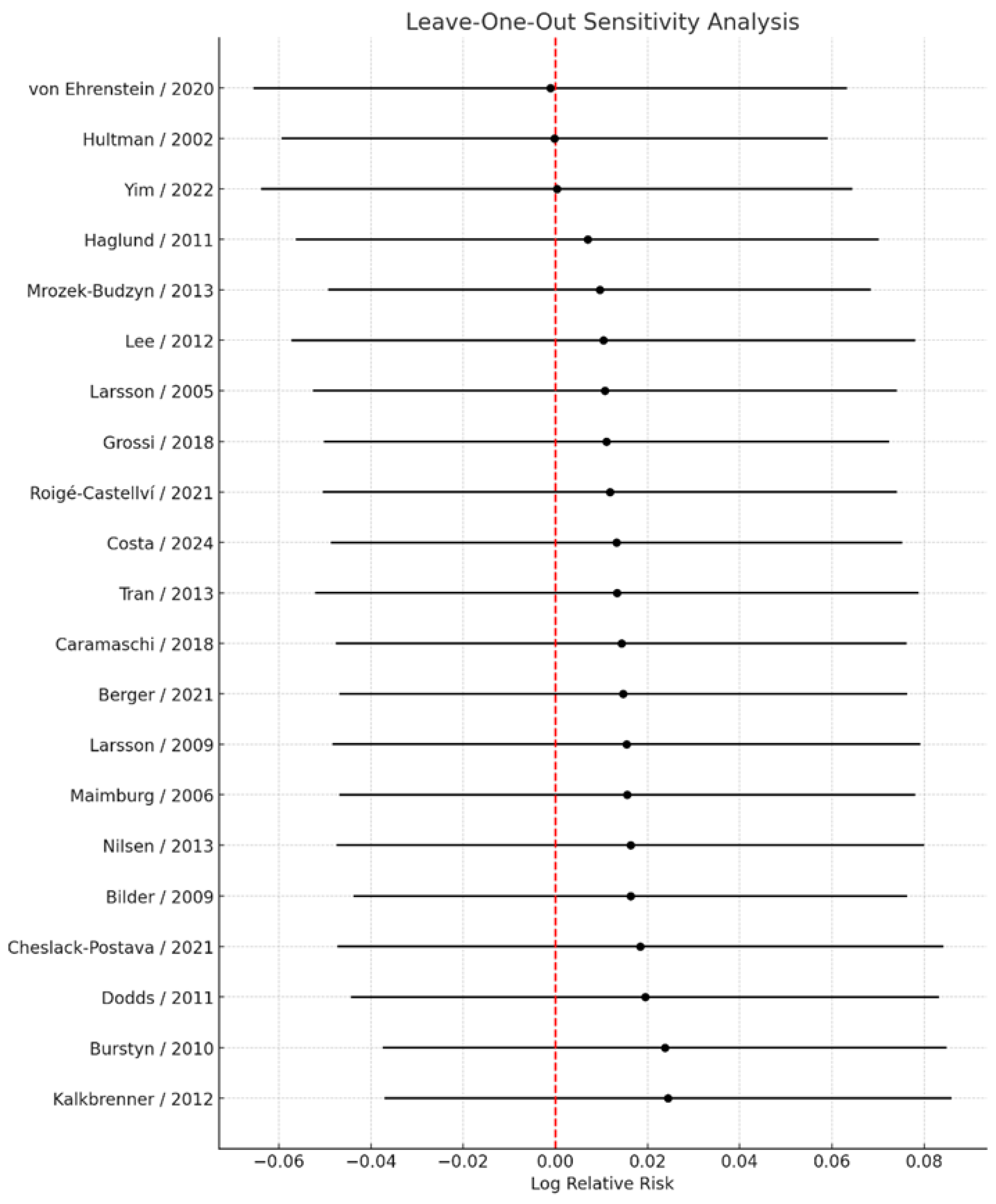

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

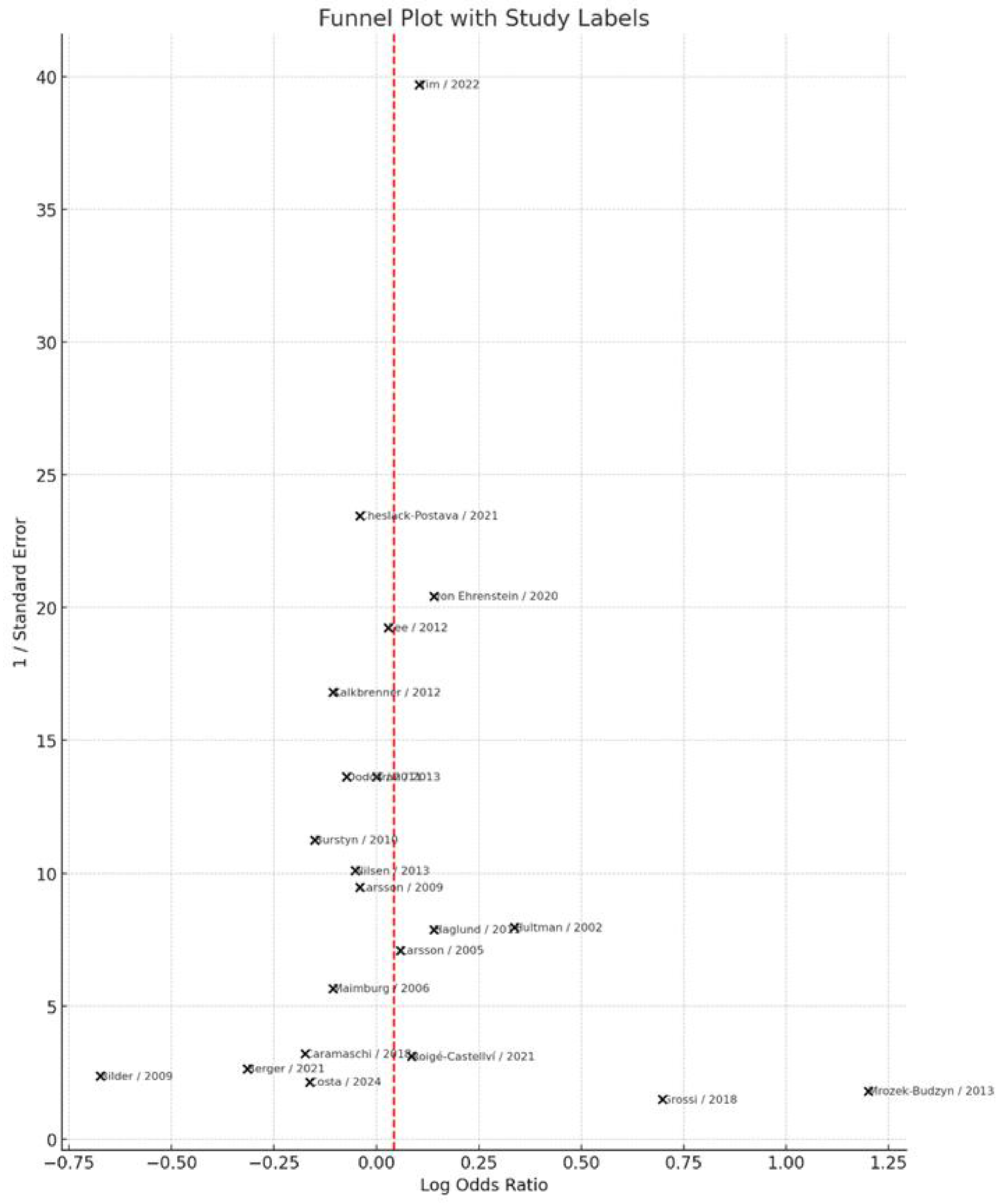

3.7. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

Recommendations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorder |

| ADDM | Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| RR | Risk Ratio |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| NOS | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| 11β-HSD2 | 11β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2 |

| StAR | Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein |

| DNMT3A | DNA Methyltransferase 3 Alpha |

| MeCP2 | Methyl CpG Binding Protein 2 |

| HDAC2 | Histone Deacetylase 2 |

References

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.A.; Williams, S.; Patrick, M.E.; Valencia-Prado, M.; Durkin, M.S.; Howerton, E.M.; Ladd-Acosta, C.M.; Pas, E.T.; Bakian, A.V.; Bartholomew, P.; et al. Prevalence and Early Identification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 4 and 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 16 Sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2025, 74, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, K.; Sarantaki, A.; Katsaounou, P.; Lykeridou, A.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Diamanti, A. Impact of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) on fetal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pneumon 2024, 37, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivilaki, V.G.; Diamanti, A.; Tzeli, M.; Patelarou, E.; Bick, D.; Papadakis, S.; Lykeridou, K.; Katsaounou, P. Exposure to active and passive smoking among Greek pregnant women. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2016, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Diamanti, A. Artificial Intelligence for Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy. Cureus 2024, 16, e63732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasi, B.; Cornuz, J.; Clair, C.; Baud, D. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes: A cross-sectional study over 10 years. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suter, M.A.; Aagaard, K.M. The impact of tobacco chemicals and nicotine on placental development. Prenat. Diagn. 2020, 40, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, D.M.; Zhang, L.; Wilkes, B.J.; Vaillancourt, D.E.; Biederman, J.; Bhide, P.G. Nicotine and the developing brain: Insights from preclinical models. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022, 214, 173355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Gong, X.; Wang, G. A meta-analysis of maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder risk in offspring. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10418–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Lee, A.M.; McKee, S.A.; Picciotto, M.R. Maternal smoking and autism spectrum disorder: Meta-analysis with population smoking metrics as moderators. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramaschi, D.; Taylor, A.E.; Richmond, R.C.; Havdahl, K.A.; Golding, J.; Relton, C.L.; Munafò, M.R.; Davey Smith, G.; Rai, D. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism: Using causal inference methods in a birth cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkbrenner, A.E.; Meier, S.M.; Madley-Dowd, P.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Fallin, M.D.; Parner, E.; Schendel, D. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking in pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder in offspring. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Cui, X.; Yan, Q.; Aralis, H.; Ritz, B. Maternal Prenatal Smoking and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A California Statewide Cohort and Sibling Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 190, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheslack-Postava, K.; Sourander, A.; Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S.; McKeague, I.W.; Surcel, H.M.; Brown, A.S. A Biomarker-Based Study of Prenatal Smoking Exposure and Autism in a Finnish National Birth Cohort. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2444–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Bilder, D.; Pinborough-Zimmerman, J.; Miller, J.; McMahon, W. Prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstyn, I.; Sithole, F.; Zwaigenbaum, L. Autism spectrum disorders, maternal characteristics and obstetric complications among singletons born in Alberta, Canada. Chronic Dis. Can. 2010, 30, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, L.; Fell, D.B.; Shea, S.; Armson, B.A.; Allen, A.C.; Bryson, S. The role of prenatal, obstetric and neonatal factors in the development of autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2011, 41, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, N.G.; Källén, K.B. Risk factors for autism and Asperger syndrome. Perinatal factors and migration. Autism 2011, 15, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, C.M.; Sparén, P.; Cnattingius, S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology 2002, 13, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.J.; Eaton, W.W.; Madsen, K.M.; Vestergaard, M.; Olesen, A.V.; Agerbo, E.; Schendel, D.; Thorsen, P.; Mortensen, P.B. Risk factors for autism: Perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M.; Weiss, B.; Janson, S.; Sundell, J.; Bornehag, C.G. Associations between indoor environmental factors and parental-reported autistic spectrum disorders in children 6–8 years of age. Neurotoxicology 2009, 30, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkbrenner, A.E.; Braun, J.M.; Durkin, M.S.; Maenner, M.J.; Cunniff, C.; Lee, L.C.; Pettygrove, S.; Nicholas, J.S.; Daniels, J.L. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, using data from the autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.K.; Gardner, R.M.; Dal, H.; Svensson, A.; Galanti, M.R.; Rai, D.; Dalman, C.; Magnusson, C. Brief report: Maternal smoking during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 2000–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimburg, R.D.; Vaeth, M. Perinatal risk factors and infantile autism. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, R.M.; Surén, P.; Gunnes, N.; Alsaker, E.R.; Bresnahan, M.; Hirtz, D.; Hornig, M.; Lie, K.K.; Lipkin, W.I.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; et al. Analysis of self-selection bias in a population-based cohort study of autism spectrum disorders. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2013, 27, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozek-Budzyn, D.; Majewska, R.; Kieltyka, A. Prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors for autism—Study in Poland. Cent. Eur. J. Med. 2013, 8, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.L.; Lehti, V.; Lampi, K.M.; Helenius, H.; Suominen, A.; Gissler, M.; Brown, A.S.; Sourander, A. Smoking during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder in a Finnish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2013, 27, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, K.; Pearl, M.; Kharrazi, M.; Li, Y.; DeGuzman, J.; She, J.; Behniwal, P.; Lyall, K.; Windham, G. The association of in utero tobacco smoke exposure, quantified by serum cotinine, and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2017–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.A.; Almeida, M.T.C.; Maia, F.A.; Rezende, L.F.; Saeger, V.S.A.; Oliveira, S.L.N.; Mangabeira, G.L.; Silveira, M.F. Maternal and paternal licit and illicit drug use, smoking and drinking and autism spectrum disorder. Cien. Saude Colet. 2024, 29, e01942023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, E.; Migliore, L.; Muratori, F. Pregnancy risk factors related to autism: An Italian case-control study in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), their siblings and of typically developing children. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2018, 9, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roigé-Castellví, J.; Murphy, M.M.; Voltas, N.; Solé-Navais, P.; Cavallé-Busquets, P.; Fernández-Ballart, J.; Ballesteros, M.; Canals-Sans, J. A prospective study of maternal exposure to smoking during pregnancy and behavioral development in the child. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, G.; Roberts, A.; Lyall, K.; Ascherio, A.; Weisskopf, M.G. Multigenerational association between smoking and autism spectrum disorder: Findings from a nationwide prospective cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 193, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.N.; Lee, B.K.; Lee, N.L.; Yang, Y.; Burstyn, I. Maternal smoking and autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz-Picciotto, I.; Korrick, S.A.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Karagas, M.R.; Lyall, K.; Schmidt, R.J.; Dunlop, A.L.; Croen, L.A.; Dabelea, D.; Daniels, J.L.; et al. Maternal tobacco smoking and offspring autism spectrum disorder or traits in ECHO cohorts. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, A.C.; Lotfipour, S. Prenatal nicotine exposure during pregnancy results in adverse neurodevelopmental alterations and neurobehavioral deficits. Adv. Drug Alcohol. Res. 2023, 3, 11628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Xia, L.P.; Shen, L.; Lei, Y.Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Magdalou, J.; Wang, H. Prenatal nicotine exposure enhances the susceptibility to metabolic syndrome in adult offspring rats fed high-fat diet via alteration of HPA axis-associated neuroendocrine metabolic programming. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, J.M.; O’Neill, H.C.; Stitzel, J.A. Developmental nicotine exposure engenders intergenerational downregulation and aberrant posttranslational modification of cardinal epigenetic factors in the frontal cortices, striata, and hippocampi of adolescent mice. Epigenet. Chromatin 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proud, E.K.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, M.; Gummerson, D.M.; Vanin, S.; Hardy, D.B.; Rushlow, W.J.; Laviolette, S.R. Chronic nicotine exposure induces molecular and transcriptomic endophenotypes associated with mood and anxiety disorders in a cerebral organoid neurodevelopmental model. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1473213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, L.; Yoon, C.D.; LaJeunesse, A.M.; Schirmer, L.G.; Rapallini, E.W.; Planalp, E.M.; Dean, D.C. Prenatal substance exposure and infant neurodevelopment: A review of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1613084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachou, M.; Kyrkou, G.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Kapetanaki, A.; Vivilaki, V.; Spandidos, D.A.; Diamanti, A. Smoke signals in the genome: Epigenetic consequences of parental tobacco exposure (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2025, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peltekidi, A.; Jotautis, V.; Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, M.; Georgakopoulou, V.E.; Sousamli, A.; Diamanti, A.; Vivilaki, V.; Orovou, E.; Sarantaki, A. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238584

Peltekidi A, Jotautis V, Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou M, Georgakopoulou VE, Sousamli A, Diamanti A, Vivilaki V, Orovou E, Sarantaki A. Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238584

Chicago/Turabian StylePeltekidi, Afroditi, Vaidas Jotautis, Maria Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, Vasiliki E. Georgakopoulou, Aikaterini Sousamli, Athina Diamanti, Victoria Vivilaki, Eirini Orovou, and Antigoni Sarantaki. 2025. "Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238584

APA StylePeltekidi, A., Jotautis, V., Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, M., Georgakopoulou, V. E., Sousamli, A., Diamanti, A., Vivilaki, V., Orovou, E., & Sarantaki, A. (2025). Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy and Risk of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8584. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238584